Especially after #MeToo, sexual harassment (SH), gender bias (GB), and gender discrimination (GD) have been reported within academic medicine across discipline and academic position. Ceppa et al found that among attending surgeons, 81% of women vs 46% of men had experienced sexual harassment.1 At a large academic medical center, the majority of faculty women (82.5%) and faculty men (65.1%) experienced at least one incident of sexual harassment from staff, students, or faculty within the previous year.2 A systematic review of SH and discrimination found a prevalence of verbal harassment ranged from 3% to 28% among medical trainees.3 Stratton et al found that GD and SH influenced medical trainees’ choice of specialty and residency program rankings.4 These experiences have implications for emotional well-being and long-term career outcomes.

To our knowledge, few qualitative studies of SH, GB, and GD in academic medicine exist.4 We previously described barriers and facilitators to reporting and responding to SH and GB in family medicine (FM).6 We found that one of the strongest facilitators for breaking the silence around these experiences was a culture that supported discussion and action around SH and GB.6,7 Wendling et al’s supporting commentary noted the

need to shine the light on our institutions and understand how our people—all of our people—are being treated, for to face that truth is to take our first step toward change.8

The literature on SH among physicians uses primarily quantitative methods and characterizes the frequency and type of harassment3 but provides little context or nuance. Further, the few qualitative studies tended to include homogenous gender (primarily women) and position (trainees or faculty) samples. We need a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the nature of SH, GB, and GD experienced in FM across gender and position in order to develop all-inclusive strategies and policies that mitigate these issues.

In this paper, we present the lived experiences of our participants in order to begin to address this need. We use qualitative data to better understand and characterize the nature, pervasiveness, and responses to SH, GB, and GD between and within men and women faculty and residents in a department of FM.

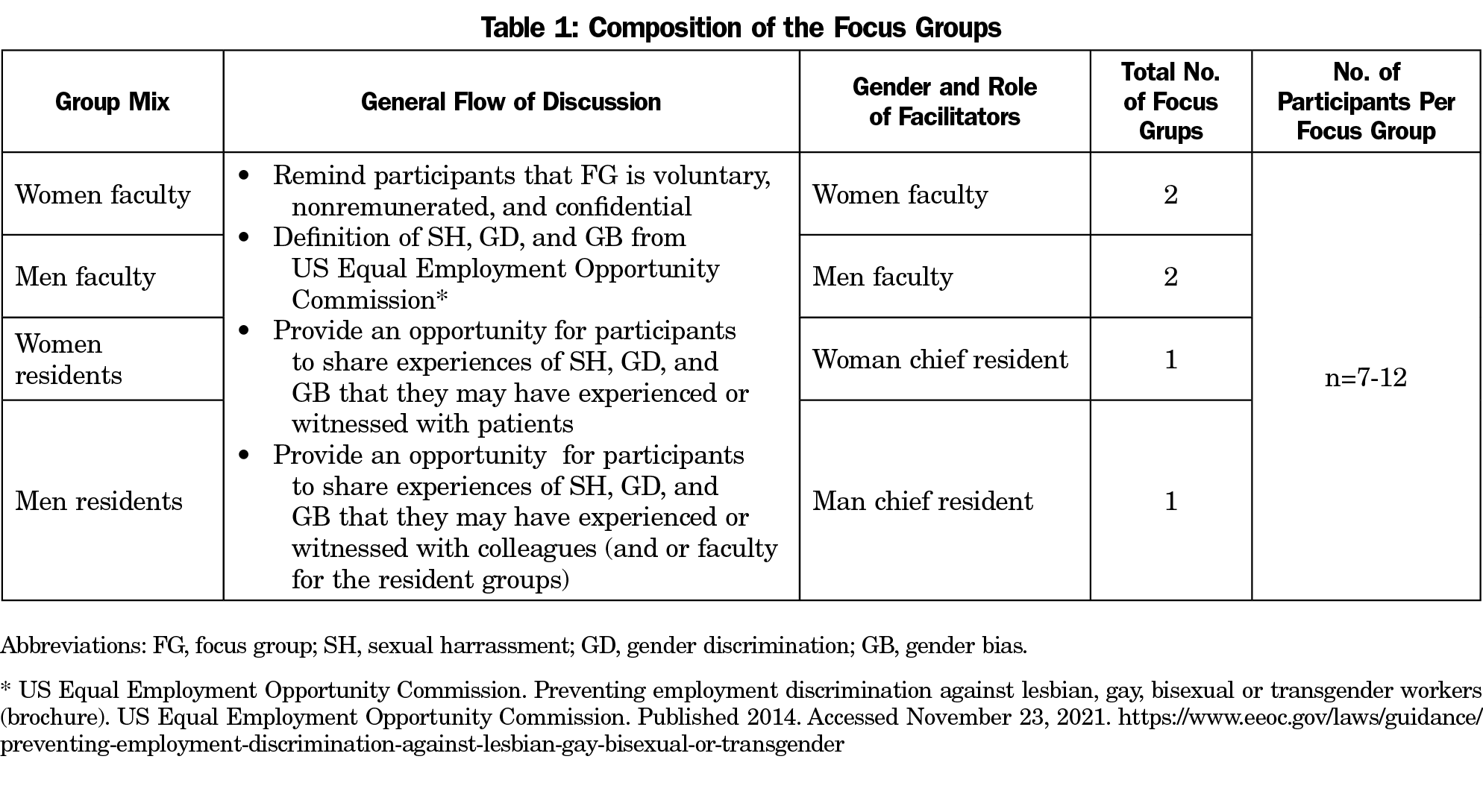

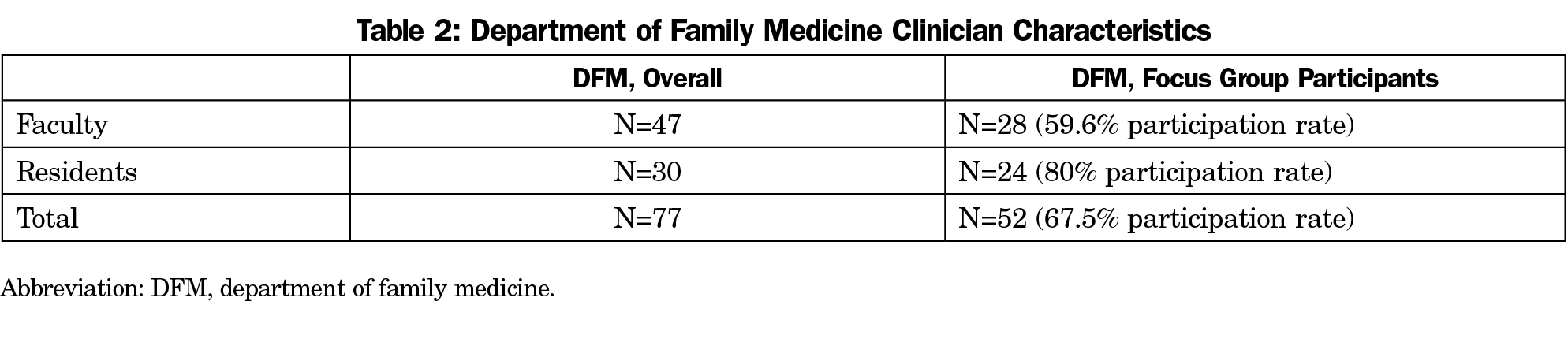

We conducted six FGs. There were four, 1-hour faculty FGs that consisted of attending physicians, behavioral health faculty, and nurse practitioners, at different career stages. The two, 2-hour resident FGs consisted of physician residents (Table 1). The FG invitation emphasized that participation was voluntary, confidential, and nonremunerated. All faculty and residents were invited to participate.

The facilitator’s gender was concordant with the FG they facilitated. Facilitators began the sessions with a review of voluntary consent for participation, assurance of confidentiality, and the expectation of confidentiality among participants. The semistructured interview began with the definitions of SH, GB, and GD from the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.9 Facilitators first asked about experiences with SH, GB, and GD with patients, which we felt to be a safer conversation than experiences with colleagues or supervisors. We concluded by asking more generally about any other experiences with SH, GB, or GD they would like to share. Our semistructured interview guide has been previously reported.6 We audio recorded each FG and had them professionally transcribed anonymously.

We used an immersion-crystallization process whereby we immersed ourselves in the data, reflected collectively on the analysis experience, and identified patterns or themes noticed during the immersion process.10 A concept was considered a code if it was noted more than once and present in at least two transcripts.

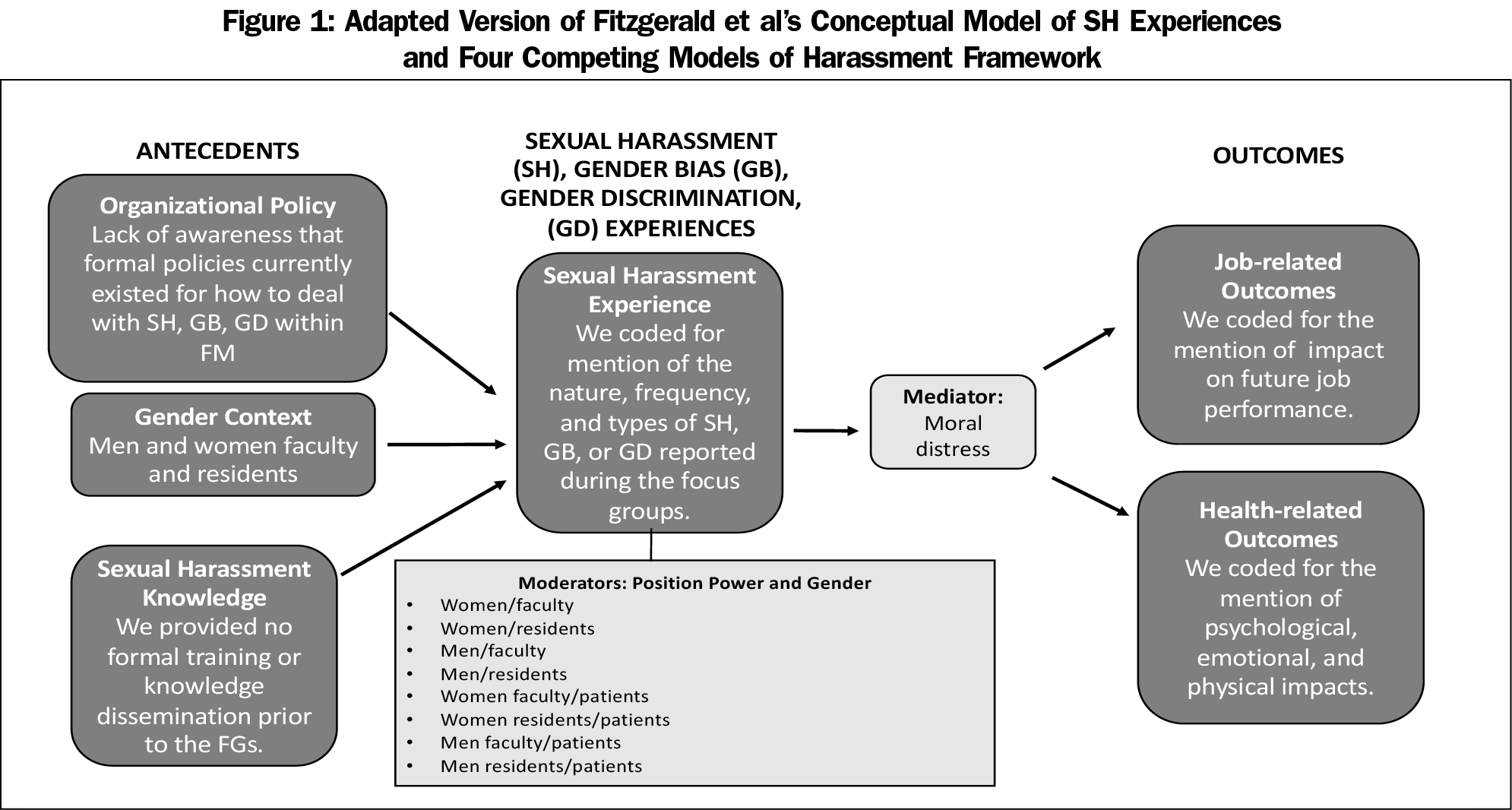

We adapted Fitzgerald et al’s model by incorporating known moderators of reported experiences with SH, GB, and GD, and a mediator of reported outcomes. We used our adapted model to explain differences in reported experiences based at the intersections of gender and/or position power among FG participants.

The team met regularly to develop the coding structure; discuss additional themes, gaps or discordances; and review continued strategies for analyses. We approved the final coding structure after four iterations. Once consensus on the coding structure occurred, each transcript was read and independently coded by two study team members. Each coder entered their independent codes into a MAXQDA database where the codes were summarized and collated for analyses. We member-checked9 the validity of our findings with faculty during regularly scheduled faculty meetings. Study team members did not code any of the transcripts for groups they facilitated. We used Fitzgerald et al’s SH Experiences model as a guiding framework to map antecedents and outcomes related to SH, GB, and GD. We adapted the model by incorporating known moderators of reported experiences with SH, GB, and GD, and a mediator of reported outcomes (Figure 1).12 Specifically, our model was used to explain differences in reported experiences based on the intersections of gender (men vs women)13 and/or position-power (trainee vs faculty vs patient vs age), as well as the impact of moral distress14 (ie, when clinicians cannot accomplish what they believe to be ethically appropriate actions) on outcomes.15 In medical training, trainees are typically, although not always, younger than attending clinicians. It was difficult to separate the effect of age and of power status, so we present the combination of these as “position-power.”

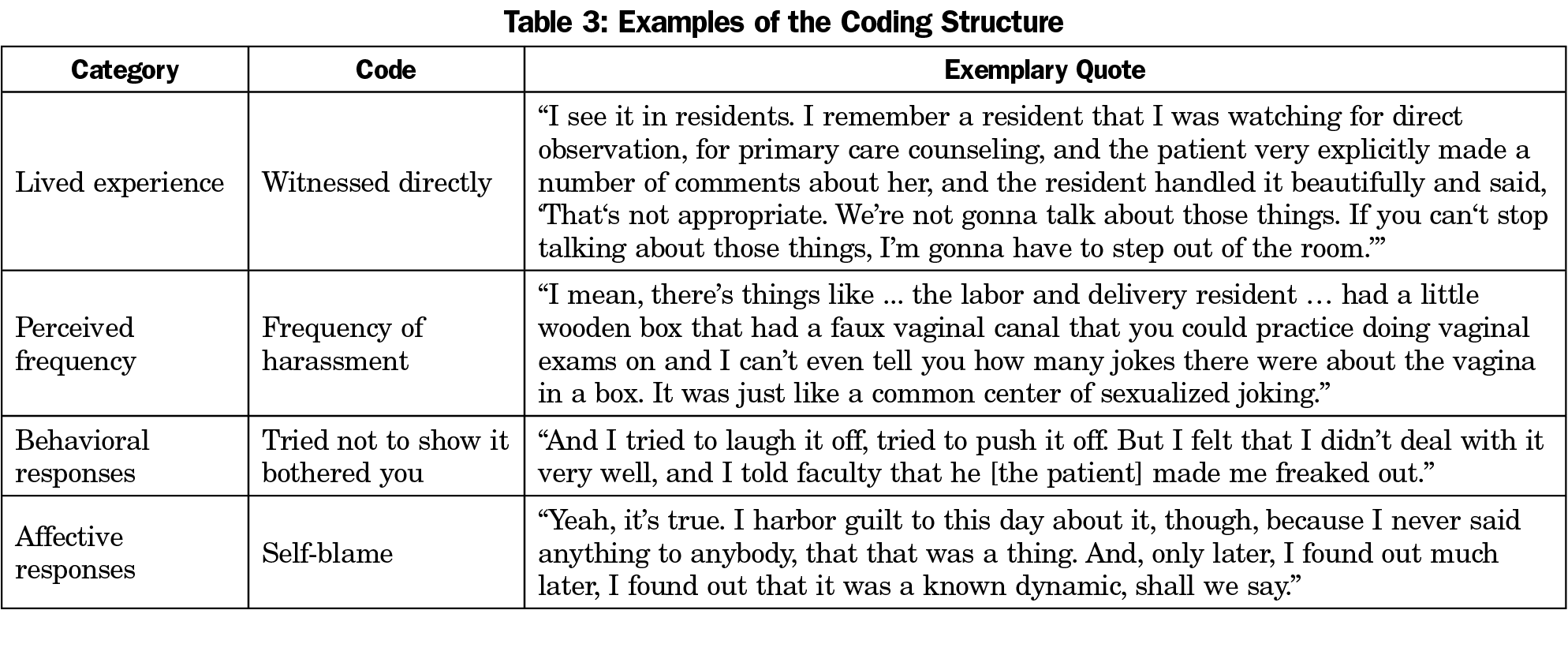

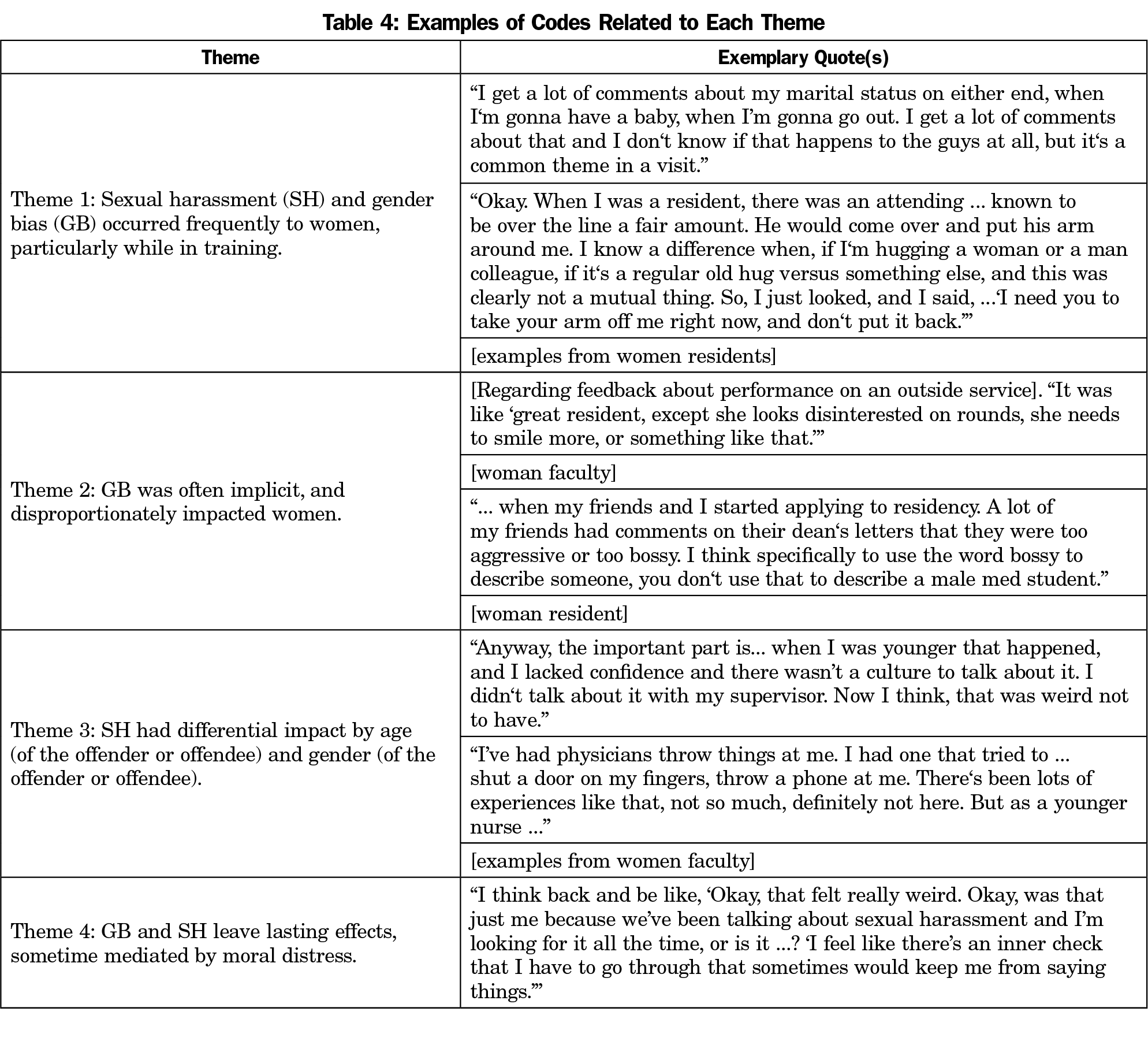

We identified four main themes: (1) SH and GB occurred frequently to women, particularly while in training, (2) GB was often implicit and disproportionately affected women, (3) SH had differential impact by age (of the offender or offendee) and gender (of the offender or offendee), and (4) GB and SH left lasting effects, sometimes mediated by moral distress. Illustrative quotes related to each code are shown in Table 3. Examples of quotes related to the more specific themes are listed in Table 4. We observed variation within some themes based on the gender of the offendee and the type of offender (patient, colleague/faculty). While the transcripts were deidentified, the gender of offender and offendee were often stated or obvious from context.

Theme 1: SH and GB Occurred Frequently to Women, Particularly While in Training. All women FGs reported frequent firsthand experiences of SH and GB. Women faculty and residents had similar experiences, but faculty reported more frequent SH when they were younger and/or in training.

Sometimes when I think about this, I feel like this happens literally almost every single day. I feel like personally I get very numb to it. Just happened to me yesterday when I was in a patient room. [Resident woman]

Most of my examples are from when I was younger also, but I don’t think that’s because it doesn’t happen now. [Faculty woman]

There were few firsthand examples of SH and GB reported in the men’s FG. However, the men did comment on how frequently these experiences occurred among women trainees.

... persistent misogyny... there’s a particular faculty member in a prominent position ... who just does this over and over again. And students will tell you this. I mean, it’s just ... over and over and over and over and over again. [Faculty man]

Dozens of times. Precepting. Patients frequently comment ... I’ll say something like, ‘You’ve got a really good doctor,’ and [they] say, ‘She’s really hot, too,’ or, ‘She’s really good looking,’ or, ‘She dresses real nice ...’ [Faculty man]

Theme 2: GB Was Often Implicit and Disproportionately Impacted Women. Many participants described experiences where patients assumed the man in the room was the physician, regardless of their actual position. There was also a tendency among patients to attribute female stereotyped gender-roles to women.

We walked in this patient’s room … The person addressed me as ‘doctor,’

and said to [the woman colleague], ‘Are you the TV lady?’ [Faculty man]

... when you walk in as a team with a female attending and perhaps a male medical student or resident and the patients will almost always address the man. [Resident woman]

A faculty woman described situations where women’s ideas are appropriated by men.

… some guy later makes your suggestion. And I say, ‘Well, I’m glad you agree with (woman colleague). She mentioned that about 10 minutes ago …’ [Faculty woman]

Theme 3: SH Had Differential Impact by Age (of the Offender or Offendee) and Gender (of the Offender or Offendee). Verbal SH was common, including statements with sexual connotations. Examples of verbal harassment included jokes, sexist remarks, and comments on physical appearance. Women commented on being distressed when being referred to with diminutive names such as “sweetness” and “cutie.”

Faculty women mentioned that as they grew older and rose in academic rank, the instances of SH declined.

… when you have gray hair, you don’t get hit on as much anymore … it definitely becomes protective. [Faculty woman]

There was some disagreement among participants about what constitutes SH when the situation involved age discordance (eg, a younger clinician and an elderly patient). A faculty man described experiencing the behavior differently based on the woman patient’s age.

It makes me feel weird … especially if they’re young … If they’re older … I’m kind of more comfortable with it. [Faculty man]

A faculty woman recalled an encounter in which a male medical student did not associate the elderly female patient’s comments with SH because of her age.

... I said, ‘But you know what, if an elderly man said that to a woman, a female doctor, we wouldn’t be okay. So were you really okay with it?’ He’s like, ‘Oh she was just a cute little old lady.’ [Faculty woman]

With patient-related SH, typically the offender was a man, and the victim a woman resident. The most commonly reported occurrence was exposure to male genitalia (eg, male patients sexualizing physical exams and having erections).

… when I was a resident in the ED … I started doing an exam without a chaperone, and he totally had an erection. [Faculty woman]

... ‘Dr [Resident’s name], I have something to show you.’ I walk back in, had his pants down and he was masturbating. [Resident woman]

A few examples included gender-concordant SH encounters with patients. There were discussions around what, if anything, the clinician would have done differently if the patient had been from the opposite sex.

When I was doing the breast exam [she said], ‘Oh that feels good.’ And I went to do the pelvic and she’s like, ‘You know, I’m used to sticking things in me. I’ll just insert the speculum myself.’ … If a man had behaved that way, I would’ve stopped the exam. [Faculty woman]

The one time I felt really uncomfortable was a very muscular, gay guy coming on to me, and I felt kinda scared, and I realized, reflecting on it, it was all about power, and that this guy was more powerful than me, and so it was the first time I got a little glimpse of what, for women, why that would be different, because it’s somebody, often, more [physically] powerful than them, and that’s scary. [Faculty man]

Theme 4: GB and SH Have Lasting Effects, Sometimes Mediated by Moral Distress. Participants commented on the psychological and emotional consequences of GB and SH, experienced directly or indirectly, leaving some participants feeling threatened and unsafe.

Some women participants struggled to resolve competing ethical principles, expressing self-blame for not setting limits with patients, placing patient care before one’s own psychological safety.

Bystanders or witnesses to discussions of verbal sexual harassment struggled with the impact of their lack of response in the moment.

A long time ago … I was overhearing women interns talking about the porn that was readily shared on surgical rounds … and how uncomfortable it made them feel … I was mortified … I feel guilty when I think about it. [Faculty woman]

A resident man reported concern about potentially being the offender in situations and not knowing it, such as making jokes that could be perceived as harassment.

My fear is that it gets to the point where nothing is safe and I’m afraid to make any comment whatsoever and I’m basically just a robot just going through the motions, … there is a time and a place for comedy in medicine. Patch Adams showed us that. [Resident man]

Several women wore their white coats in hopes of preventing SH or GB among patients. They reported using the coat for safety, essentially, to cue the patient to their position as a doctor and to be addressed as a professional. The men in our FGs did not discuss these types of personal protective strategies.

‘Yes, I may be the same age as your granddaughter, but look at this white coat, I’m a doctor.’ I don’t know, I’ve kept that barrier. [Resident woman]

I used to keep a white coat for when I would see patients like him to put on over whatever I was wearing that day. [Faculty woman]

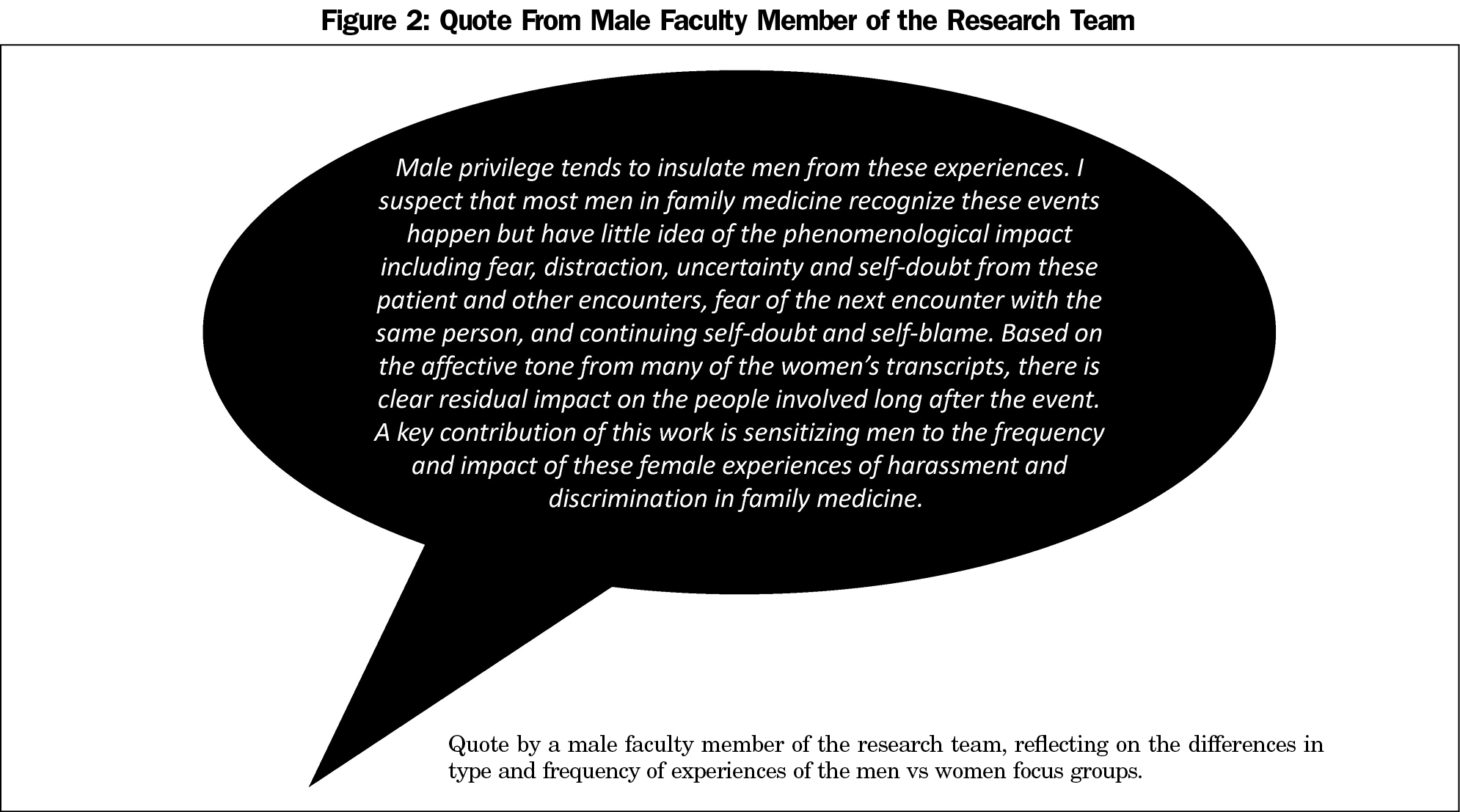

Several faculty men expressed doubt about the existence or pervasiveness of SH, GB, and GD in the department. A male member of the research team was surprised by the frequency of the women’s experience and some of the content of the results (Figure 2).

The purpose of this study was to qualitatively identify SH, GB, and GD in an academic DFM practice. Furthermore, we aimed to identify factors that may explain the differential impact of these experiences. Most recent studies, conducted across academic department specialties, explored homogenous groups (ie, trainees only) and are quantitative.2,15,16 Similar to previous reports, our results reveal that SH and GB are common experiences.17-19 All our FGs included physical and verbal examples that involved patients, faculty, and colleagues.21 Other studies have shown that SH and GB are underreported,21-23 and we assume that many other experiences went unspoken in our groups.

As in other studies,1 women participants experienced most of the incidents. The participants reported a range of experiences from explicit harassment to gender-based microaggression. Our finding that women clinicians use their white coats as protection by reinforcing their professional status has also been reported in the literature.24-27

Despite the increased awareness of SH and GB, our findings show that men and women clinicians in the same department have different experiences and perspectives regarding the scope of these issues. Men remain largely shielded from the direct impact of these situations and rarely felt unsafe. Similar to Farkas’ findings, among our participants, men experienced SH differently from women and struggled to define some of these events as harassment. In our study, men were generally more accepting of SH encounters with older women patients, and felt conflicted about how to respond to younger patients who communicated sexual attraction. With these exceptions, our male FGs struggled to recall personal experiences and instead spent more time discussing hypotheticals.

Our findings have important implications for research and policies related to mitigating SH and GB in academic medicine. Most studies have been gender-homogenous and focused on quantitative reports of SH and GB, while providing less qualitative context, nuance, or impact. Our descriptions of the multiple actors, contexts, and outcomes can help leaders and policy makers tailor strategies to anticipate and address these issues in multistakeholder environments such as FM.

First, we suggest patient care policies should include mitigation strategies for reducing moral distress in clinicians. For example, a policy that requires a clinician to continue providing care to a sick patient despite their inappropriate SH behavior (first do no harm) may in fact be harmful to the clinician. These situations are not trivial, as moral distress has been associated with perceived lack of support from peers, burnout, and lack of involvement in decision making.12,13,29 Second, trainings should consider how to address gender stereotypes from patients, as well as responses to SH from gender-concordant and age-discordant patients.

We recently published participants’ experiences of barriers and facilitators to reporting.6 Our next steps include department scenario training. Our goal is to develop a culture that encourages open conversations about SH and GB experiences, increases sensitivity through direct feedback, encourages help-seeking by any offendee, decreases distress among those directly or indirectly affected, and builds skills for all of us in responding to bias and harassment in clinical environments.

There are no comments for this article.