Background and Objectives: Residents in difficulty are costly to programs in both time and resources, and encountering difficulty can be emotionally harmful to residents. Approximately 10% of residents will encounter difficulty at some point in training. While there have been several studies looking at common factors among residents who encounter difficulty, some of the findings are inconsistent. The objective of this study was to determine whether there are common factors among the residents who encounter difficulty during training in a large Canadian family medicine residency program.

Methods: Secondary data analysis was performed on archived resident files from a Canadian family medicine residency program. Residents who commenced an urban family medicine residency program between the years of 2006 and 2014 were included in the study.

Results: Five hundred nine family medicine residents were included in data analysis. Residents older than 30 years were 2.33 times (95% CI: 1.27-4.26) more likely to encounter difficulty than residents aged 30 years or younger. Nontransfer residents were 8.85 times (95% CI: 1.17-66.67) more likely to encounter difficulty than transfer residents. The effects of sex, training site, international medical graduate status, and rotation order on the likelihood of encountering difficulty were nonsignificant.

Conclusions: Older and nontransfer residents may be facing unique circumstances and may benefit from additional support from the program.

The prevalence of residents who encounter difficulty in training has been reported to be about 10% across most medical specialties.1 In an assessment of a family medicine residency program over a period of 25 years, the prevalence of residents in difficulty was found to be 9.1%.2 Residents in difficulty require costly remediation,2,3 additional time investments from program directors,4,5 and may pose a risk to patient safety.6,7

Identification of common factors among residents in difficulty may aid in earlier detection of residents in need of additional support. While this has not been an active area of research, some published literature suggests that trainees who are older,5,6,8,9 international medical graduates (IMGs),5,8,9 or who have transferred from another residency training program,9 may be more likely to encounter difficulty in their training than their respective counterparts. Other research identified location of training,3,8 and sex of trainees8,9 as risk factors for encountering difficulty. However, findings across some of these studies are inconsistent and sometimes conflicting, demonstrating a need for additional research. Further, there is a paucity of research that looks specifically at family medicine residents who encounter difficulty.

We performed a secondary data analysis of archived resident files at a Canadian family medicine residency program to answer the following question: “Are there common factors among family medicine residents who encounter difficulty during their 2 years of training?”

Context

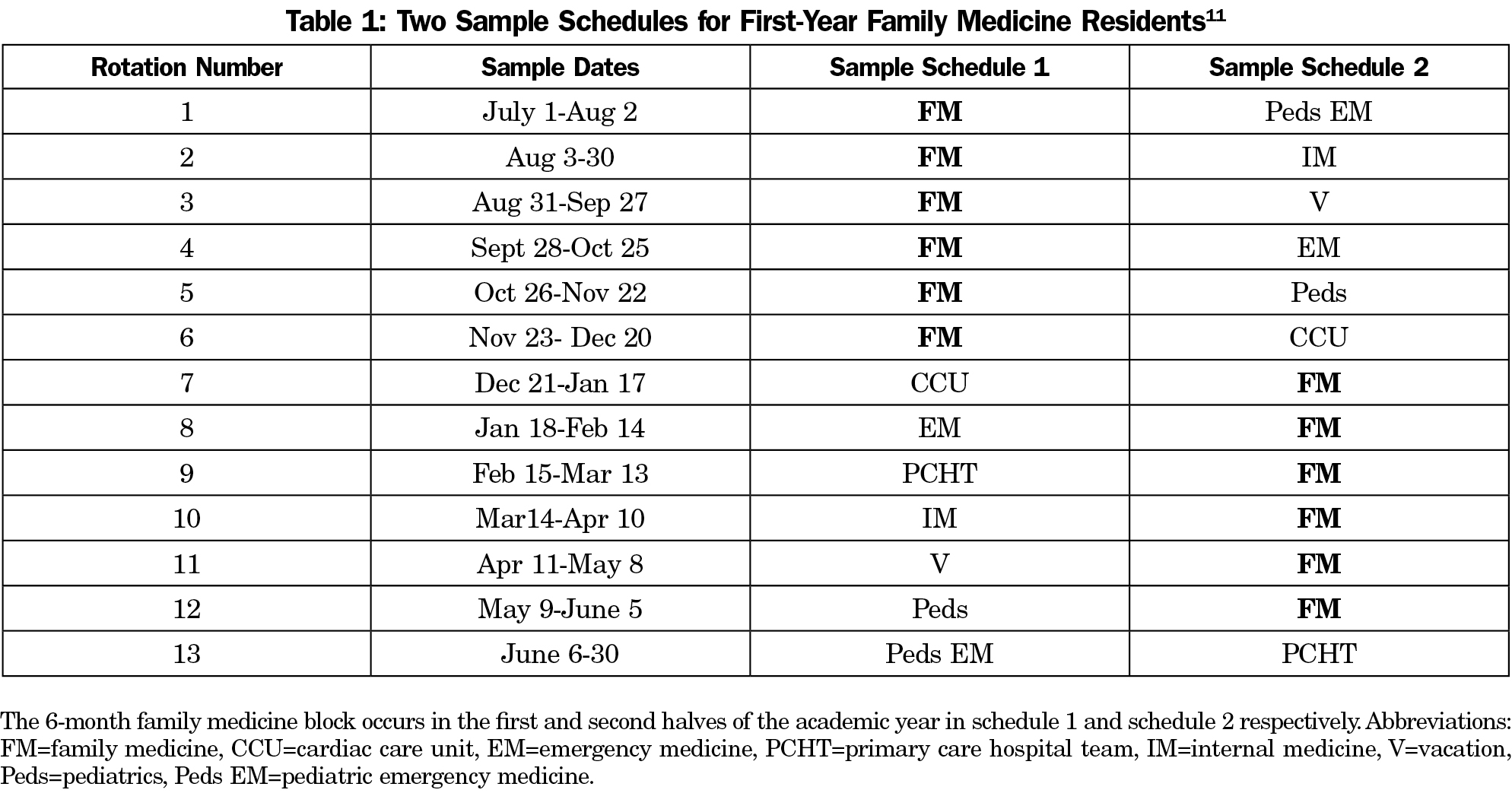

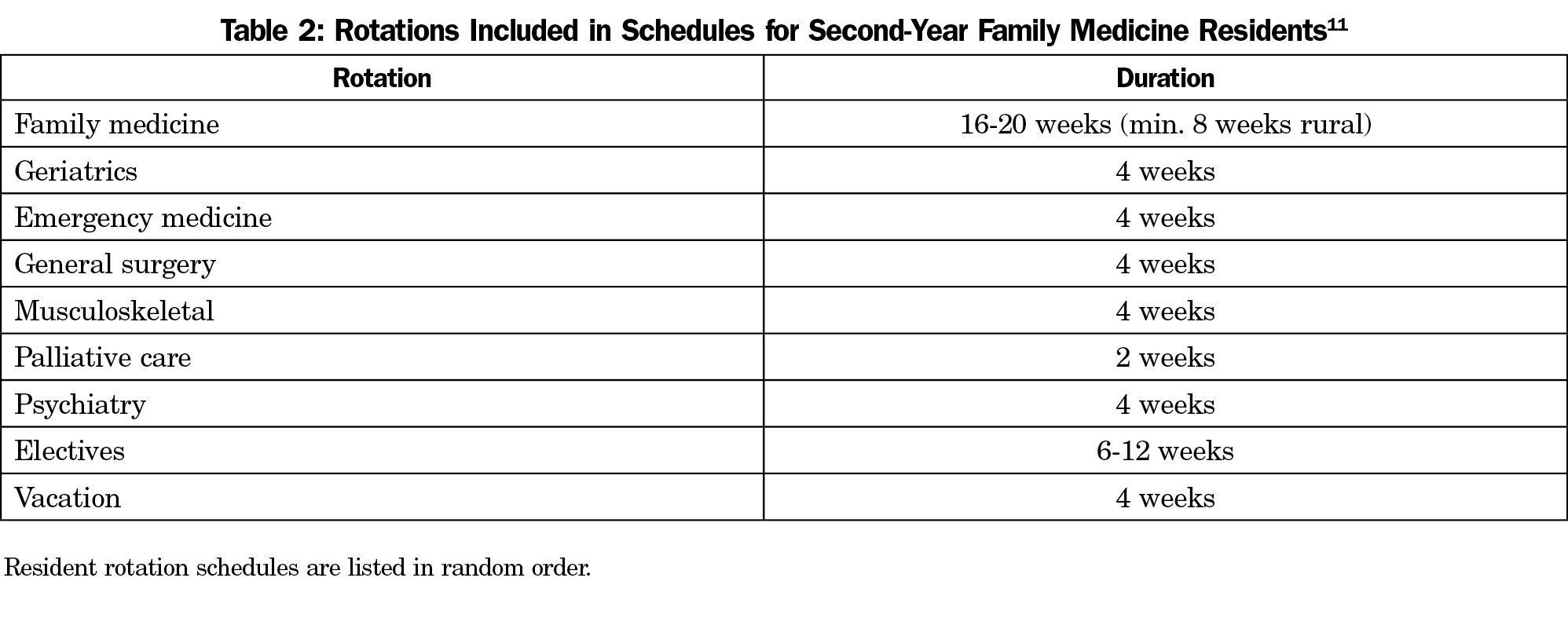

This study was conducted in a Canadian family medicine residency program. In Canada, family medicine residency is a two-year program, with most training occurring in community (outpatient) family medicine clinics. Residents also have inpatient experiences on specific rotations (Tables 1 and 2). In the program studied, assessment of resident performance in a rotation is captured on an in-training evaluation report (ITER), which is completed by a clinical assessor from the rotation; if concerns are indicated on the ITER, it is considered a “flagged” ITER.

Measures

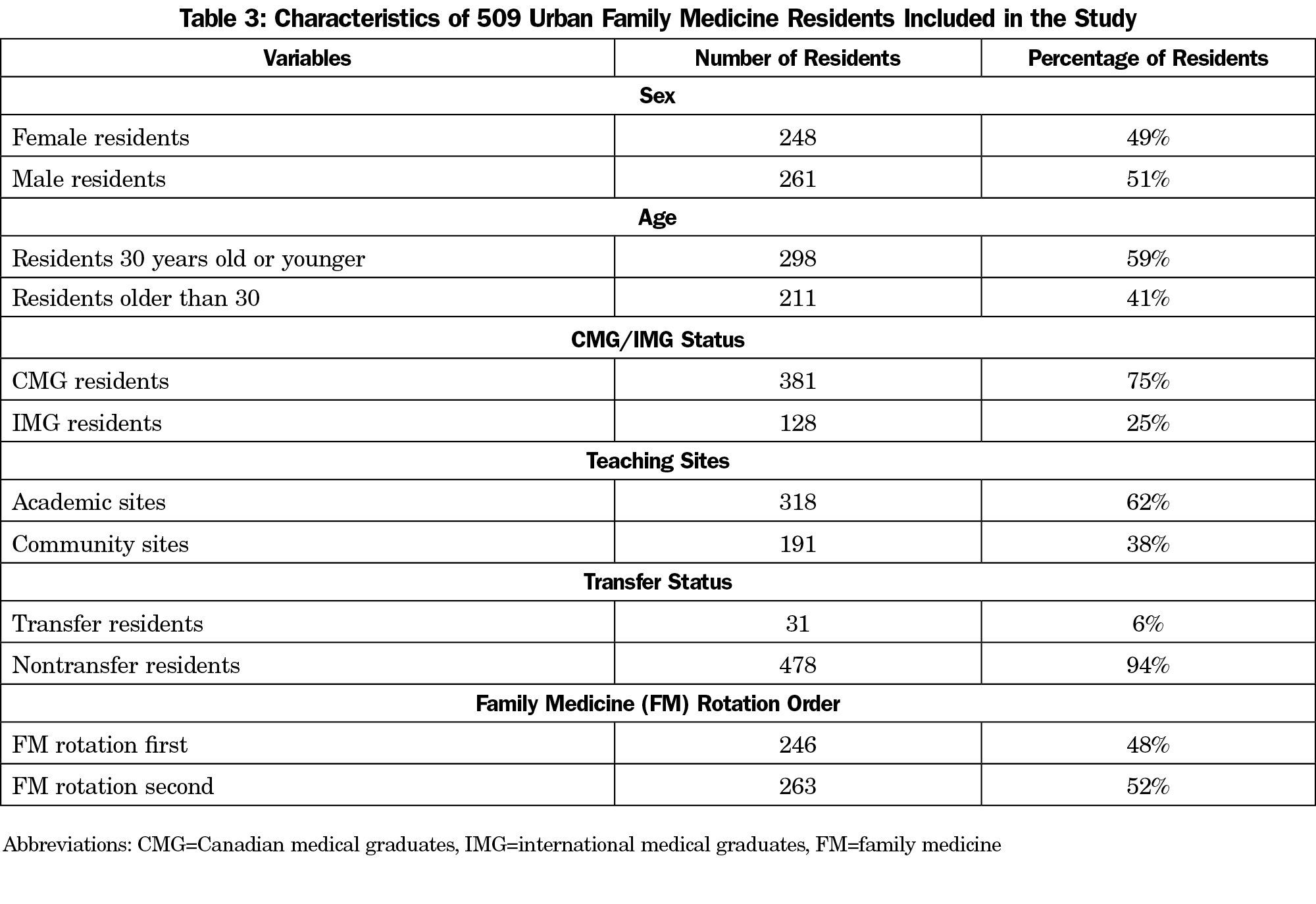

Ethics approval was obtained prior to study commencement. The department of family medicine provided the following information: sex, date of birth, medical school attended, residency start date, assigned teaching site, and rotation order for each resident. Residents who completed medical school in Canada were classified as Canadian medical graduates (CMG), otherwise they were classified as international medical graduates (IMG). Teaching sites were classified as academic or community locations according to the classifications used by the residency program.10 It was recorded whether residents had their 6-month outpatient family medicine block in the first or second half of their first year of residency (Table 1).11

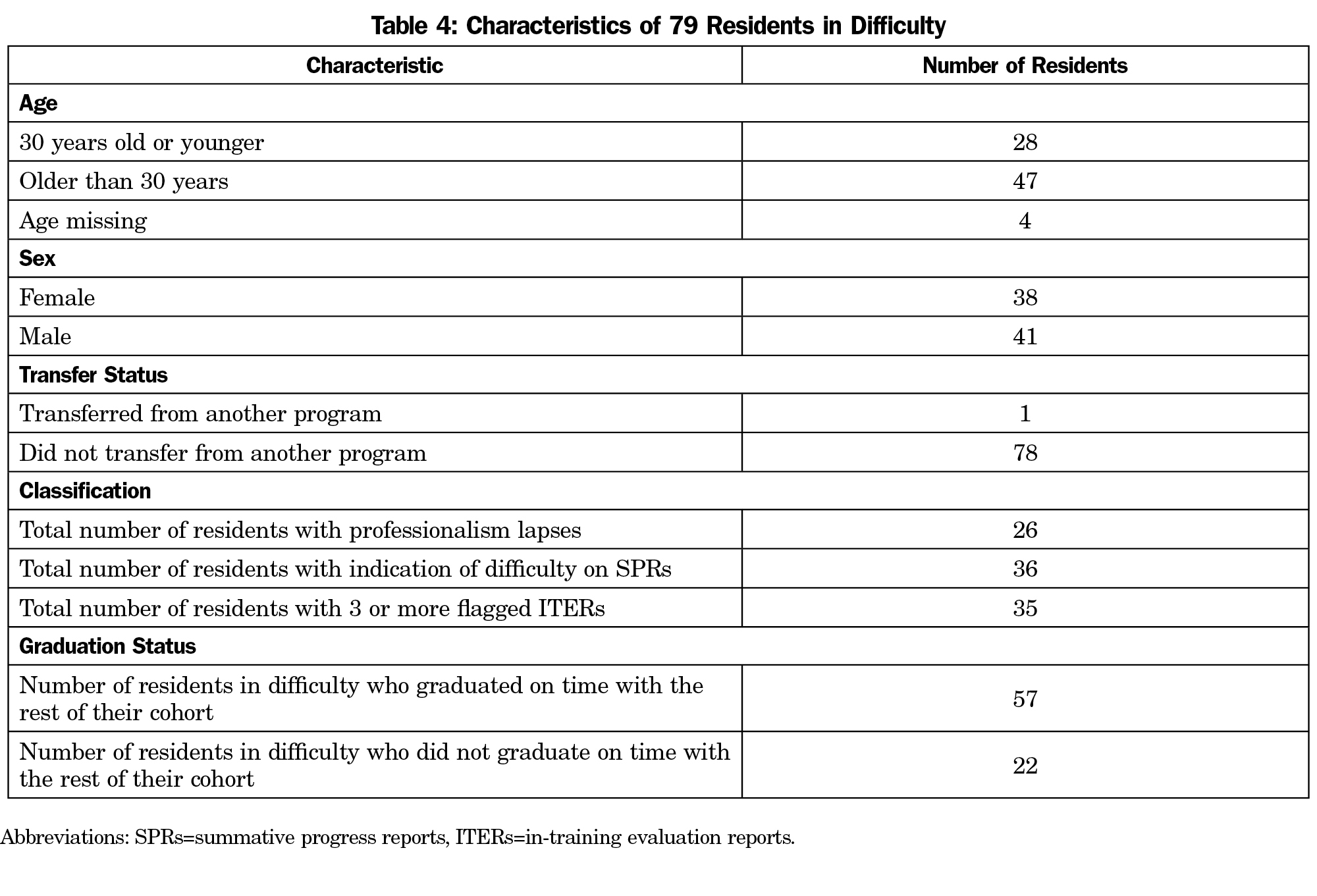

Each resident file was examined for evidence of transfer from another residency program, professionalism lapses, flagged ITERs, and indication of difficulty on summative progress reports (SPRs). Residents with any of the following were classified as residents in difficulty: (1) documented professionalism lapse, (2) three or more flagged ITERs, or (3) SPRs indicating that the student needs focused attention or remediation. <

Participants

Participants were family medicine residents who commenced their urban residency training in the source program between the years 2006 and 2014. At the residency program, there are two streams: urban and rural. The urban stream differs from the rural stream in numbers and demographics of residents enrolled and in the length and scheduling of family medicine rotations. Since the majority of residents (75%) are enrolled in the urban stream, only urban residents were included in the study.

Analysis

SPSS 22.0 was used for data analysis. Logistic regression was performed to determine whether the following learner variables were associated with encountering difficulty during training: sex, age, teaching site, CMG/IMG status, transfer from another residency program, and rotation order. A new competency-based assessment system was introduced into the residency program in 2010. In the regression analysis, we controlled for this change by creating a two-category variable to indicate which residents underwent residency training before or after the change.

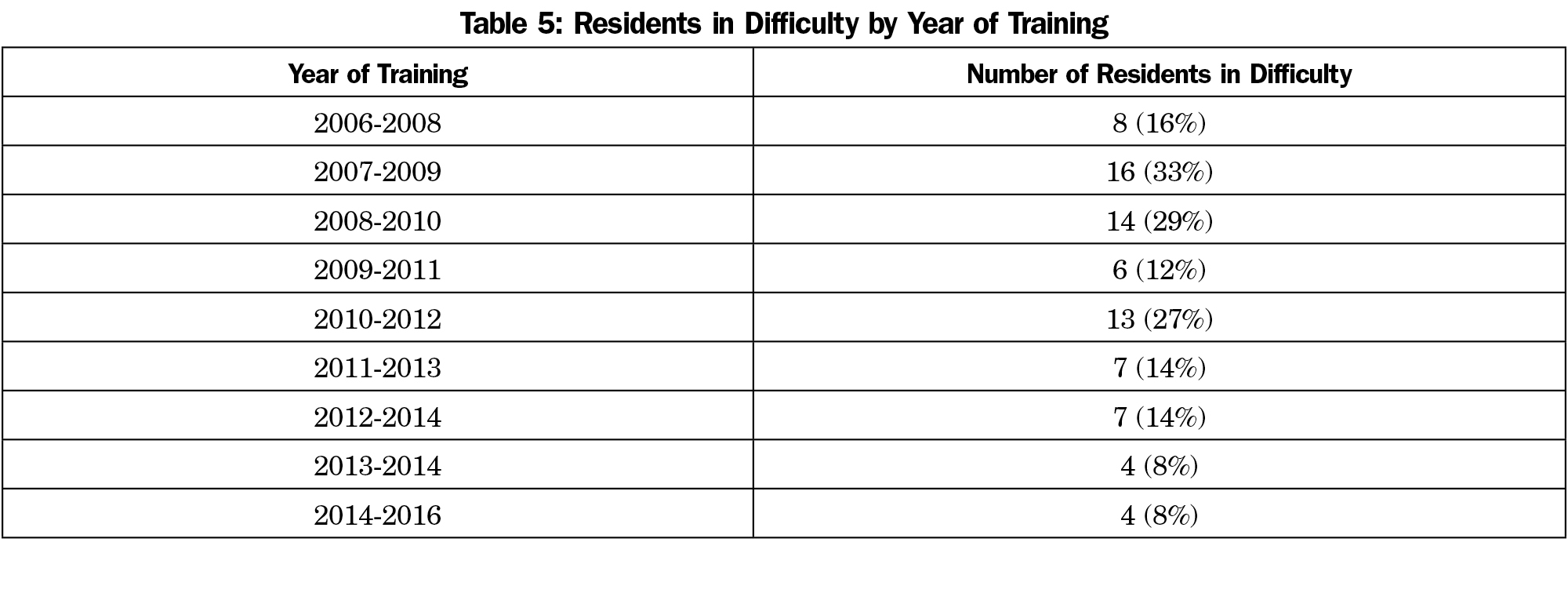

We analyzed files of 517 urban family medicine residents (100% of all urban program residents 2006-2016). Date of birth was missing in eight resident files. Thus, only 509 files (98%) were included in logistic regression (Table 3). From 2006 to 2016, 79 residents (16%) were determined to be in difficulty (Table 4). There was a trend of decreasing percentages of residents in difficulty, with 16% of residents in difficulty in the 2006-2008 cohort and 8% in the 2014-2016 cohort (Table 5).

The logistic regression model was statistically significant (χ2(7)=34.777, P<.0001). The model explained 11.7% (Nagelkerke R2) of the total variance in the outcome and correctly classified 85.3% of residents in difficulty. Residents older than 30 years were 2.33 times (95% CI: 1.27-4.26) more likely to encounter difficulty than residents aged 30 years or younger. Nontransfer residents were 8.85 times (95% CI: 1.17-66.67) more likely to encounter difficulty than transfer residents. The effects of sex, training site, IMG/CMG status, and rotation order on the likelihood of encountering difficulty were nonsignificant.

We examined whether there are common factors among residents who encounter difficulty in an urban family medicine residency program. Older age and lack of prior residency training appeared to be associated with the likelihood of encountering difficulty.

It is possible that older residents have more familial obligations, which can impact their academic performance. Further, older residents might have taken time off between medical school and residency. Marriage and time off between medical school and residency were shown to be associated with a higher likelihood of encountering difficulty during training.9

A further finding was that nontransfer residents were more likely to encounter difficulty than transfer residents, which is contradictory to findings in the existing literature.9 Transfer residents are those who begin residency training in one specialty and decide that they have not made the right choice. These residents will have undergone varying lengths of training in another specialty before they switch to family medicine. As a result, these residents will often have had clinical and didactic training experiences that would transfer to their new program in an advantageous way. Additionally, in this institution, transfer spots are highly competitive and the residents accepted as transfers have to demonstrate acceptable performance on past rotations. It is unclear whether these requirements are present at other institutions, which may explain why findings in this study differ from previously reported findings.9 Further, transfer residents may receive credit for past rotations relevant to family medicine, depending on how well residents perform in the family medicine program. Our program directors observed that transfer residents tend to be highly motivated to perform well, so that they may obtain credit for past training. We speculate that this may act as a protective factor against some of the circumstances that might lead other residents to struggle; however, this is an area that warrants further research.

This study did not explore the level of training at which residents encounter difficulty. Therefore, it may be possible that transfer residents enter the program beyond the level of training where most nontransfer residents encounter difficulty.

In family medicine residency training, older residents were more likely to encounter difficulty than younger residents. Residents who transferred from another residency program were less likely to experience difficulty than nontransfer residents. These findings suggest that older residents may be facing unique circumstances and may require additional support from the program. Findings further suggest that transfer residents have a increased likelihood of success in family medicine residency training.

Acknowledgments

Financial support provided by Health Professions Education Research Summer Studentship, Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry, University of Alberta.

References

- Tabby DS, Majeed MH, Schwartzman RJ. Problem neurology residents: a national survey. Neurology. 2011;76(24):2119-2123.

https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821f4636.

- Reamy BV, Harman JH. Residents in trouble: an in-depth assessment of the 25-year experience of a single family medicine residency. Fam Med. 2006;38(4):252-257.

- Dupras DM, Edson RS, Halvorsen AJ, Hopkins RH Jr, McDonald FS. “Problem residents”: prevalence, problems and remediation in the era of core competencies. Am J Med. 2012;125(4):421-425.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.12.008.

- Williamson K, Quattromani E, Aldeen A. The problem resident behavior guide: strategies for remediation. Intern Emerg Med. 2016;11(3):437-449.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-015-1367-5.

- Yao DC, Wright SM. National survey of internal medicine residency program directors regarding problem residents. JAMA. 2000;284(9):1099-1104.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.9.1099.

- Vermeulen MI, Kuyvenhoven MM, de Groot E, et al. Poor performance among trainees in a dutch postgraduate GP training program. Fam Med. 2016;48(6):430-438.

- Tamblyn R, Abrahamowicz M, Dauphinee D, et al. Physician scores on a national clinical skills examination as predictors of complaints to medical regulatory authorities. JAMA. 2007;298(9):993-1001.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.9.993.

- Christensen MK, O’Neill L, Hansen DH, Norberg K, Mortensen LS, Charles P. Residents in difficulty: a mixed methods study on the prevalence, characteristics, and sociocultural challenges from the perspective of residency program directors. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):69.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0596-2.

- Guerrasio J, Brooks E, Rumack CM, Christensen A, Aagaard EM. Association of characteristics, deficits, and outcomes of residents placed on probation at one institution, 2002-2012. Acad Med. 2016;91(3):382-387.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000879.

- University of Alberta Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry. Learning Sites. https://www.ualberta.ca/family-medicine/postgraduate/learning-sites. Accessed September 2, 2017.

- University of Alberta. Department of Family Medicine home page. https://www.ualberta.ca/family-medicine.