Background and Objectives: Many patients with behavioral health disorders do not seek or receive adequate care for their conditions. Among those that do, most will receive care in a primary care setting. To best meet this need, clinicians will need to demonstrate proficiency of behavioral health skills and evidence-based practices. We sought to explore the degree to which these skills are being taught in family medicine clerkships.

Methods: The Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) 2016 survey of clerkship directors (CDs) was sent to 141 CDs at US and Canadian medical schools with a required family medicine run course. CDs were asked about the inclusion of behavioral health topics, tools, and techniques in the clerkship, as well as rating the importance of these items.

Results: Eighty-six percent of CDs completed the survey. Mood disorders (81.4%) were most frequently taught, followed by anxiety disorders (77.8%), substance use disorders (74.4%), and impulse control disorders (39.1%). Screening tools and behavioral health counseling skills were less commonly taught.

Conclusions: Many behavioral health topics are not taught universally to all family medicine clerkship students. Gaps exist between what is included in current curriculum and what is recommended by the National Clerkship Curriculum for family medicine. These gaps may represent challenges for improving the care for patients with behavioral health disorders.

Mental illness is highly prevalent in primary care settings. In the United States, lifetime prevalence of a behavioral health disorder approximates 50%.1 More than half of patients in treatment for mental illness receive their care by primary care clinicians.2-3 Many barriers exist to receiving mental health care outside of the primary care setting.2 Moreover, a significant population of patients exists with both mental health disorders and chronic medical problems.4-5 Because of these findings, it is important for primary care physicians to learn about mental health disorders as well as the evidence-based screening instruments and techniques that are used to treat them.

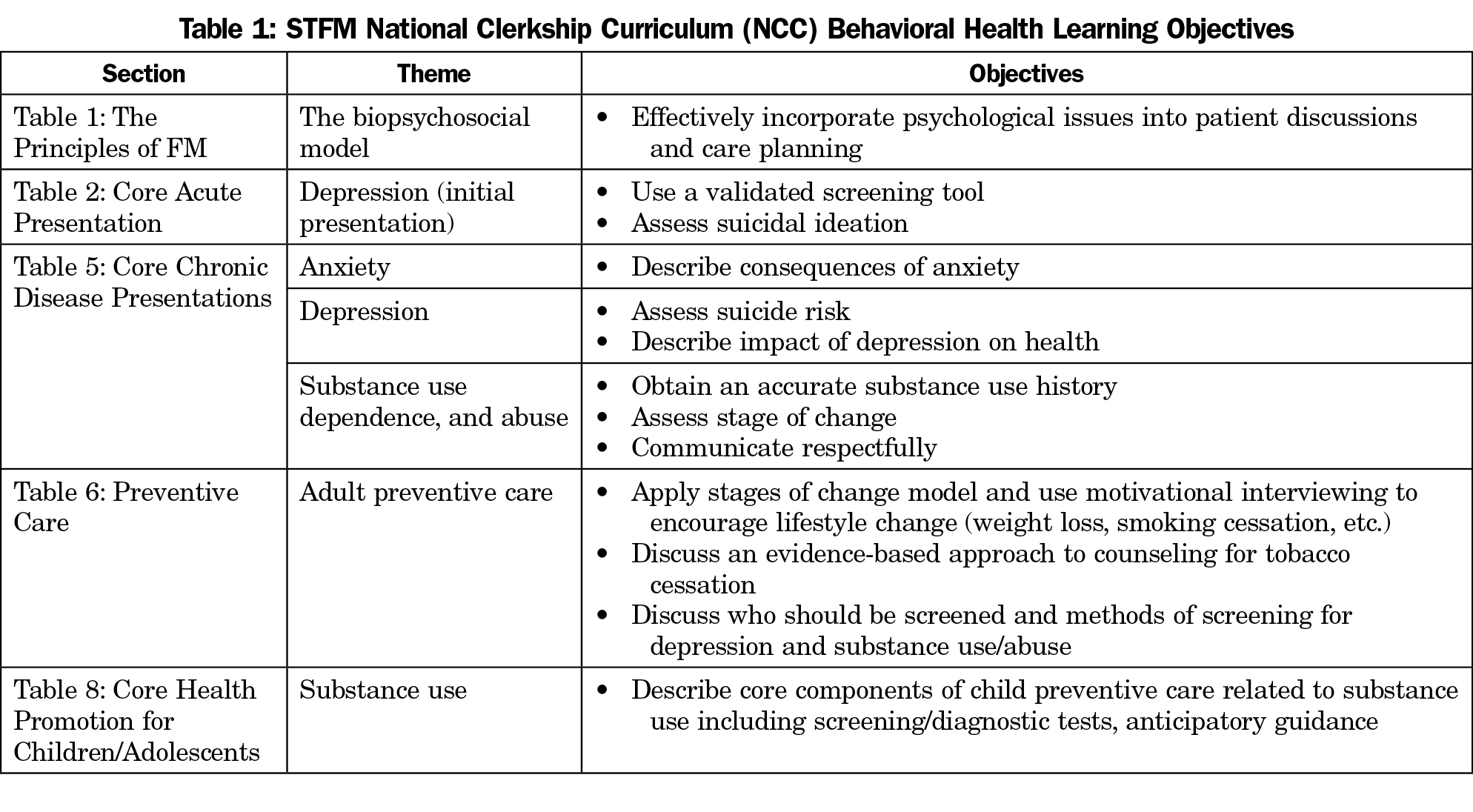

The STFM National Family Medicine Clerkship Curriculum (NCC) developed in 2012 specifically highlights several components of behavioral health care as core tasks for family medicine clerkship students.6-7 The curriculum includes topics such as depression, anxiety, and substance use as well as the use of validated screening tools and behavioral change frameworks (Table 1).

Although behavioral health is a broad term, the most common classes of behavioral health disorders in order of decreasing lifetime prevalence include: anxiety disorders (28.8%), impulse control disorders (24.8%), mood disorders (20.8%), and substance use disorders (14.6%).1 While instruction in behavioral health topics can be wide ranging and longitudinal across the medical school curriculum, we focused on the most prevalent mental health conditions because of their clinical significance as well as their overlap with the spectrum of primary care.

To date, little has been done to study how behavioral and physical health are currently integrated in medical school curricula.8 As a result, there is incomplete understanding of how medical students can best learn the skills necessary to incorporate behavioral health interventions into clinical practice. In addition, prior research demonstrates that the values of clerkship directors can influence the curriculum that they deliver.9 The purpose of this study was to determine the behavioral health topics, tools, and techniques taught in the family medicine clerkship and whether clerkship director characteristics were associated with whether they were likely to be taught.

We gathered and analyzed data as part of the 2016 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine clerkship directors. CAFM is a joint initiative of four major academic family medicine organizations, including the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine, the North American Primary Care Research Group, the Association of Departments of Family Medicine, and the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors. The complete scope of the annual CERA survey process has been reported previously.10

The survey was emailed to 125 US and 16 Canadian family medicine clerkship directors between August 9, 2016 and October 9, 2016. Invitations to participate in the study included a personalized greeting and a letter signed by the presidents of each of the four sponsoring organizations with a link to the survey, which was conducted through the online program SurveyMonkey. Nonrespondents were also contacted through personal email and telephone calls to verify their status as clerkship directors, to check accuracy of email addresses, and to encourage participation. The study was approved by the American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board.

Survey Questions

The survey asked clerkship directors (CDs) basic demographic information about their schools, clerkships, and the number of students in each medical school graduating class. It also asked when they graduated from residency and how many years they have served as clerkship director. Additional questions assessed whether the following mental health topics were formally taught in the family medicine clerkship: mood disorders, anxiety disorders, impulse disorders, and substance use disorders. These topics were identified based on prevalence in the United States.1 We identified screening tools recognized in practice guidelines that directly related to these prevalent conditions: Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), Adult ADHD Self Report Scale (ASRS-V1.1), and Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) or AUDIT-C. We conducted a search of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) National Guideline Clearinghouse to identify US guidelines that addressed the management of the mental health conditions identified above. This process identified: Stages of Change, Motivational Interviewing, BATHE (Background, Affect, Trouble, Handling, Empathy), SBIRT (Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment), 5As (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange), and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). We asked respondents to rate the importance of these tools and techniques on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 was not at all important and 5 was extremely important. To determine whether a mental health topic, tool, or technique was perceived as important, we dichotomized the 5-point Likert scale into “important” (4 or 5) or “unimportant” (3 or below).

Analyses

Descriptive statistics summarized demographic variables and prevalence of topics and tools taught in the clerkship. Fisher’s exact test was used to identify associations between perceived importance and teaching. Adjusted logistic regression was used to test an independent association between teaching topics and the paired screening tools. Clerkship characteristics that were adjusted for include clerkship region, public or private institution status, clerkship format, and total length of clerkship.

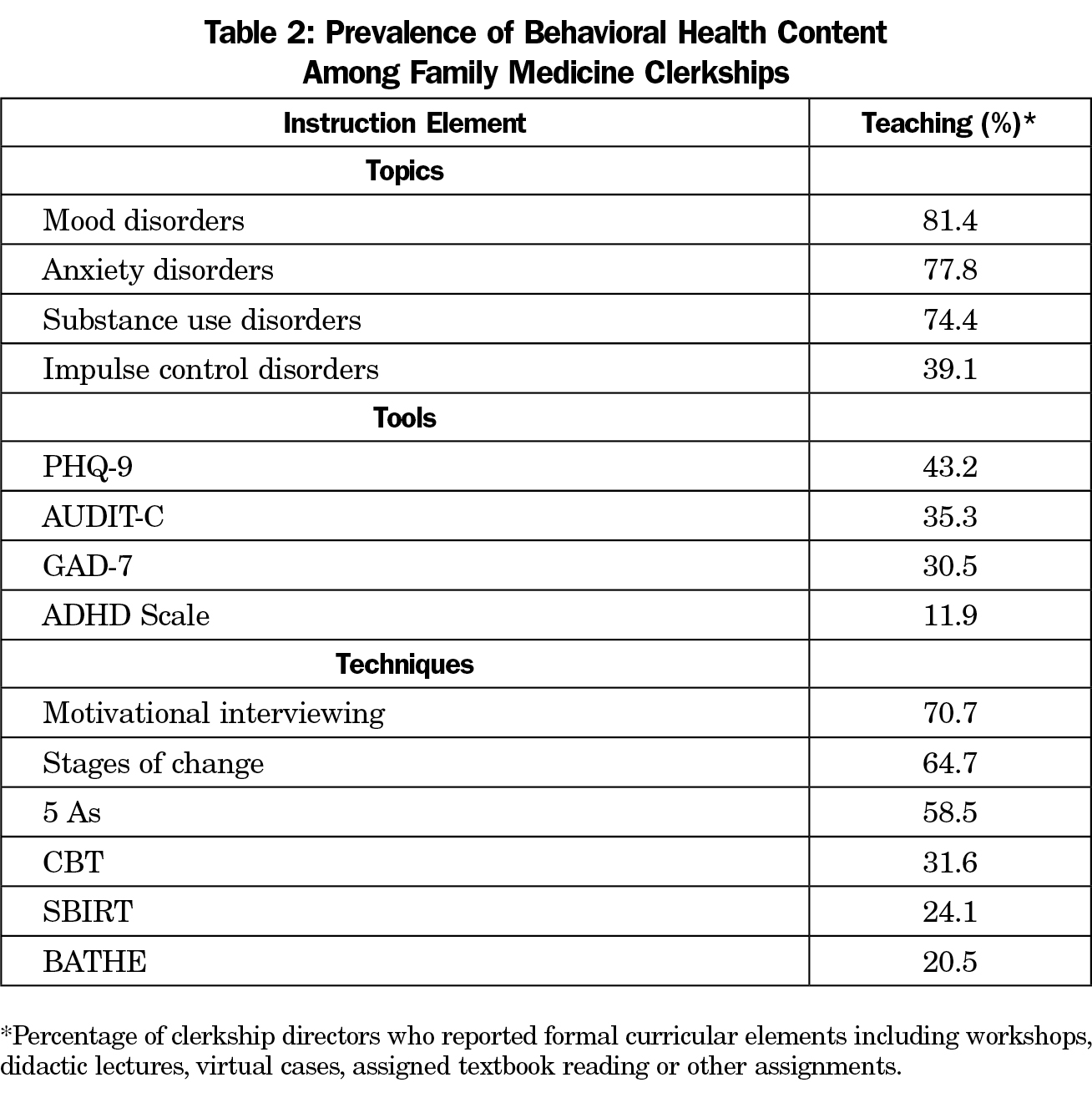

The overall response rate to the CERA survey was 86% (121 of 141 responding). The subset of respondents who answered the questions regarding behavioral health (n=118) were used for our analyses. The most frequent mental health topics taught in the family medicine clerkship were mood disorders (81.4%), followed by anxiety disorders (77.8%), substance use disorders (74.4%) and impulse control disorders (39.1%, Table 2).

The prevalence of screening tools taught in the family medicine clerkship ranged from 11.9% (ADHD Scale) to 43.2% (PHQ-9). Among various treatment techniques, motivational interviewing was the most likely to be taught (70.7%) followed by Stages of Change (64.7%), 5 As (58.5%), CBT (31.6%), SBIRT (24.1%), and the BATHE technique (20.5%).

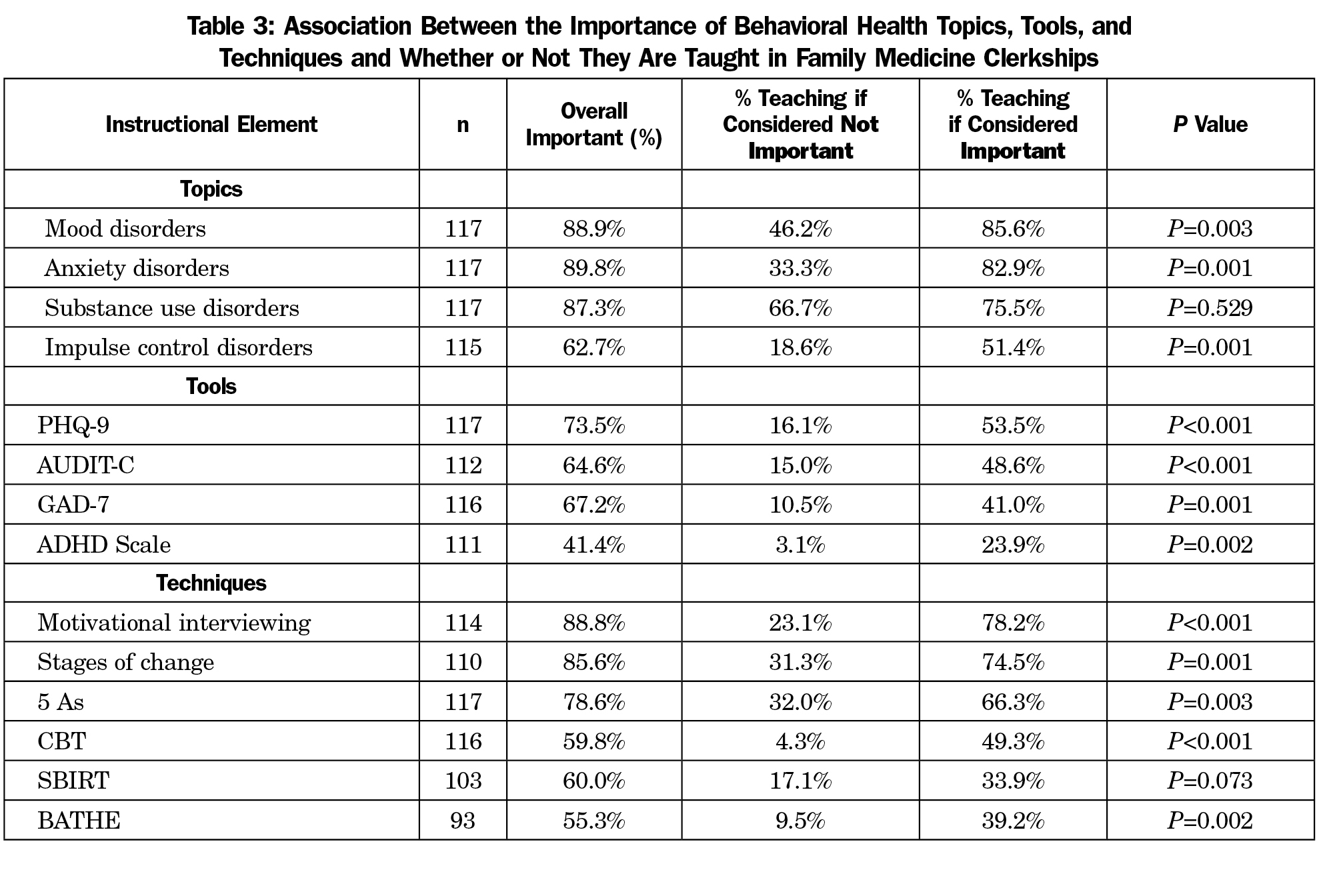

Of the named topics, tools, and techniques listed in Table 2, the proportion of respondents who rated the issue as important to include in the family medicine clerkship was reported (Table 3). Our analysis revealed that topics, tools, and techniques were more likely to be taught in the clerkship if the clerkship director thought them to be important. For example, clerkship directors who thought teaching mood disorders was important were more likely to teach about mood disorders (85.6% vs 46.2%, P=0.003). Clerkship directors who thought mental health screening tests were important were more likely to include them in the curriculum (Table 3).

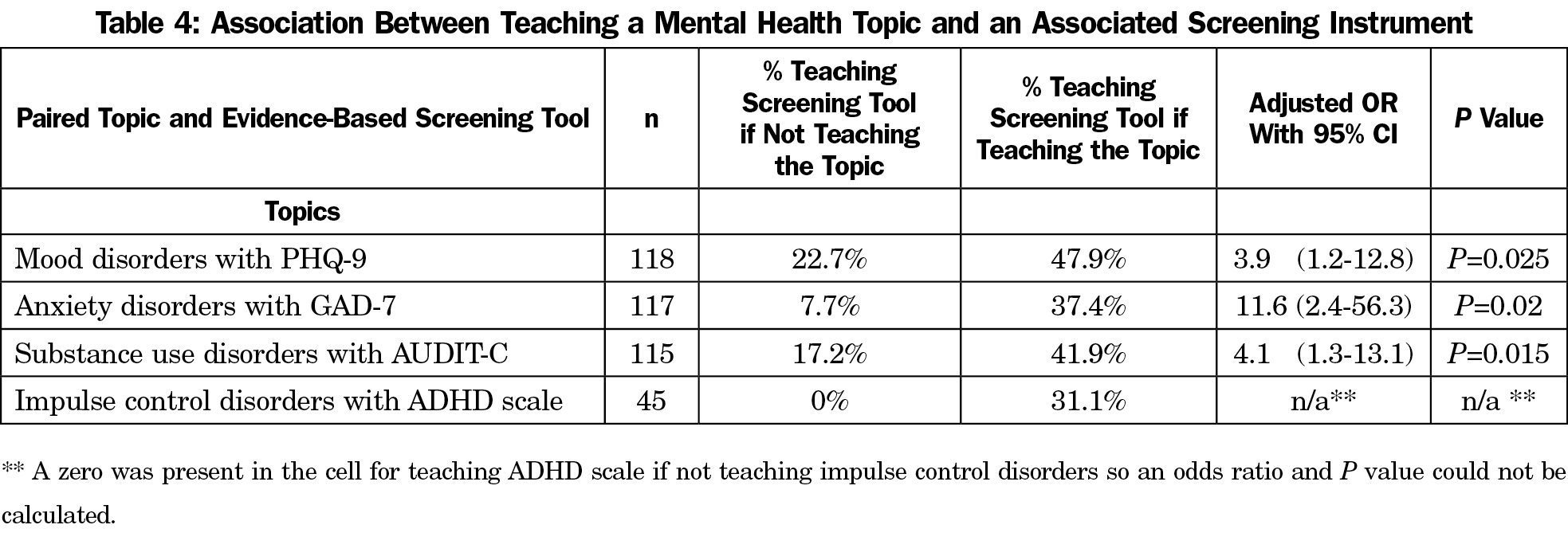

Among clerkships that teach each of the selected topics of mental health disorders, there is an association with whether or not a paired screening tool was also taught (Table 4). For example, among respondents who reported teaching mood disorders, 47.9% state that they also teach the PHQ-9 screening tool.

In this study, we sought to describe the pattern and degree of education surrounding common topics, tools, and techniques that are utilized in behavioral health care. In our survey of family medicine clerkship directors, we discovered that gaps exist in what is being taught to family medicine clerkship students related to some of the most prevalent mental health diagnoses seen in primary care. For instance, one quarter (25.6%) of family medicine clerkships reported that they have no formal curricular elements that educate students on substance use disorders, and 60.9% do not report teaching impulse and behavioral control disorders such as ADHD or conduct disorder in the primary care clerkship, even though the lifetime prevalence of that class of disorders is 24.8%.1

Effective treatment for behavioral health disorders relies on the ability of primary care clinicians to accurately screen for and diagnose mental health disorders when present. Our results show that many students on family medicine clerkships are not taught about the most widely used and evidence-based screening tools during their family medicine clerkship. Even when there is formal curriculum for mental health topics (eg, mood disorders), the teaching does not always extend to include use of those tools. For example, while most institutions report inclusion of mood disorders in their curriculum (81.4%), less than half of those that teach it also teach the PHQ-9 (47.9%). CDs may consider exchanging didactic instruction time to focus on these clinical skills rather than content which may be delivered elsewhere in the curriculum.

To add perspective to our study, there has been increased encouragement of clinical techniques to provide brief intervention (BATHE, SBIRT) by national primary care and mental health organizations.11 Despite efforts to expand their adoption, those techniques are not commonly taught in current family medicine clerkship curriculum (BATHE, 20.5%, SBIRT, 24.1%). This finding is consistent with a prior 2014 CERA study which discovered that only 18% of clerkship directors reported inclusion of SBIRT, and the majority of those that did include it do not use a formal curriculum.11

Our findings contrast with many of the objectives listed in the NCC (Table 1). While the NCC is not a required curriculum, it may be considered a blueprint that maps out priorities that define the family medicine specialty, overlapping with the care that is predominately provided and addressing societal need. Our findings should prompt CDs to compare their own curriculum to the specific behavioral health skills highlighted in the NCC objectives to identify opportunities to meet this suggested national standard. More importantly, we believe that items which we have shown to have high importance among CDs and which are not already part of the NCC to be considered for possible inclusion as the NCC adapts to changes in the medical education environment as well as national health care priorities.

Strengths and Limitations

A notable strength of our study is the high response rate (84%), which encompasses schools with a variety of formats and durations in a wide geographic distribution including the United States and Canada. This allows our results to be generalizable across many models of undergraduate medical education. Also, the study focused on the most prevalent mental health conditions in primary care, making it relevant to nearly all learners in medical school. Furthermore, the study utilized the well-validated CERA study mechanism, which also contributes to generalizability.

Secondly, the study looked at conditions based on population prevalence and accepted national practice guidelines. Because of this, the conclusions of the present study can help align their curriculum with the needs of our health care system.

A limitation of our study is that the survey was only sent to directors of the family medicine clerkship and only assesses content taught within that portion of the curriculum. It is recognized that instruction in mental health takes place in both preclinical experiences as well as clinical clerkships besides family medicine. However, it has been reported that behavioral health topics are more likely taught during the family medicine clerkship than any other clinical rotation other than psychiatry.8 Moreover, most mental health symptomatology presents first at the primary care level, so this care, and therefore training, needs to be integrated into primary care education.

Another limitation is that due to survey space, not every screening test for the topic conditions was assessed. Topics were chosen due to prevalence in society, and the screening tests and management techniques were selected for relevance to these conditions and based on their recommendation in national guidelines, inclusion on the NCC, and their reported high clinical utility in primary care settings.

The results of this study provide insight into the forces that influence behavioral health curriculum. We identified that despite mention in the STFM National Clerkship Curriculum, key concepts are not universally included in all family medicine clerkships, providing an opportunity to enhance fidelity to suggested standards. Perceived importance of many of the items studied increases the likelihood that those skills are taught. Understanding how CDs are influenced by and can influence the NCC may help family medicine educators develop more efficient ways to enhance behavioral health education during family medicine clerkships. Finally, the discrepancy between the prevalence of the conditions studied and the frequency with which they are included as content in family medicine clerkships provides an additional opportunity for alignment of societal health needs with learner content during medical school training.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Mara McAdams DeMarco for statistical analysis support as well as the clerkship director respondents to the 2016 CERA survey.

Project Support: This project was supported by a HRSA grant (HRSA-6 UHIHP29964-01-01).

Presentations: A portion of this manuscript was presented at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference in San Diego, CA, May 5-9, 2017.

References

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602.

https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593.

- Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):603-613.

https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603.

- Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system. Epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(2):85-94.

https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140007001.

- Scott KM, Lim C, Al-Hamzawi A, et al. Association of mental disorders with subsequent chronic physical conditions: world mental health surveys from 17 countries. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(2):150-158.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2688.

- Barile JP, Mitchell SA, Thompson WW, et al. Patterns of chronic conditions and their associations with behaviors and quality of life, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E222.

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. STFM National Clerkship Curriculum http://www.stfm.org/Resources/STFMNationalClerkshipCurriculum. Accessed February 22, 2017.

- Chumley H, Chessman A, Hobbs J, et al; Family Medicine Clerkship Curriculum Implementation task force. STFM unveils the national family medicine clerkship curriculum website. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(3):275-276. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1412.

- Dubé B, Verduin ML. A brief examination of integrated care in undergraduate medical education. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(4):457-460.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-015-0332-y.

- Ledford CJ, Seehusen DA, Chessman AW, Shokar NK. How we teach U.S. medical students to negotiate uncertainty in clinical care: a CERA study. Fam Med. 2015;47(1):31-36.

- Cochella S, Liaw W, Binienda J, Hustedde C. CERA: clerkships need national curricula on care delivery, awareness of their NCC Gaps. Fam Med. 2016;48(6):439-444.

- Carlin-Menter SM, Malouin RA, WinklerPrins V, Danzo A, Blondell RD. WinklerPrins V, Danzo A, Blondell RD. Training family medicine clerkship students in screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for substance use disorders: A CERA study. Fam Med. 2016;48(8):618-623.

There are no comments for this article.