Background and Objectives: Incoming family medicine (FM) residents start residency with different levels of procedural training. Understanding their baseline skill level is necessary to plan the educational experiences and teaching methods that will provide the desired knowledge, skills, and attitudes related to performing medical procedures.

Methods: A survey of 69 procedures based on the core list issued by the College of Family Physicians of Canada was administered to incoming residents in Alberta (Calgary and Edmonton FM programs). The survey intended to identify the levels of training and confidence acquired for each listed procedure before residency, and plans to perform each of the procedures in future independent practice.

Results: A total of 146 residents from both programs responded to the survey (82% response rate). Of the 69 procedures evaluated, 15 (21.7%) had been previously performed at least five times by 50% or more residents. Only five procedures were rated by 80% or more of the residents as being able to perform independently or to teach to others: simple suture, infiltration of local anesthetic, intramuscular injection, cryotherapy of skin lesions and Pap smear. More male residents than female residents felt confident in performing 10 procedures, while female residents were more confident in performing Pap smears. Rural residents felt more confident to perform 22 procedures than their urban colleagues.

Conclusions: This information demonstrates limited prior training in procedures among entering residents, and provides guidance to FM programs to develop teaching interventions to achieve competence in those procedural skills seen as necessary for family physicians.

The performance of procedures is an integral part of any family doctor’s skills. Unfortunately, teaching procedures to medical learners has traditionally been an assumed activity that is seldom structured and rarely based on educational objectives.1-3 Training in procedures is part of a continuum that starts in medical school and continues through residency education,4 but the degree of skills training has varied in recent decades. Previous surveys conducted in US medical schools during the 1990s reported that no procedural skills were formally taught to medical students other than venous phlebotomy.5 More recently, medical schools across North America have incorporated more procedure training.6-8 As students enter the specialty of family medicine (FM), training should continue to develop or improve the procedural skills required for practice. For this reason, FM associations and academic entities have issued lists of procedures required during residency training along with guidelines and learning objectives based on competencies required for certification.9-13

Medical students admitted to family medicine residency programs have a wide range of experience and abilities in procedural skills as they arrive from different medical schools across Canada and elsewhere (international medical graduates [IMG]). This creates the need to clearly identify the procedural skills training obtained before residency to determine the educational experiences needed to provide the desired knowledge, skills, and attitudes related to learning medical procedures.2,14

Residency programs traditionally assume exposure to common procedures before residency,15 but incongruities are found between programs’ expectations and the incoming resident’s abilities to perform common procedures.3,16-19 Furthermore, medical school graduates have reported lack of confidence in performing procedures.20-22 Understanding their level of procedural training can guide curricular planning23 and can help postgraduate programs to determine whether specific teaching interventions are needed for different groups of residents.

Previous studies have also found differences in procedural experience between trainee genders during residency, as male residents had performed relatively more procedures overall during training, while female residents had performed more IUD insertions and obstetrical care.24 Other studies found variation in procedural skills experiences was a function of training location, identifying that more rural residents felt confident to practice procedures and had plans to perform them in the future than urban residents. However, it is unclear whether this is due to differences between those who enter such programs, rather than what is taught in them.25,26 For this reason, identifying the procedural skills training needs of specific groups of residents at the beginning of residency, as well as areas of lack of confidence in performance,27-28 will allow programs to determine groups of procedures or specific procedures in which residents may require more training in order to adequately prepare them for independent practice.

The objective of this study was to understand what procedural skills Alberta family medicine residents have at program entry, and whether those skills differ according to the resident’s gender or admission to urban or rural training.

Research Design

A survey was administered to residents early in their first year (PGY1) in family medicine programs at the University of Calgary and the University of Alberta. The study received ethical approval from the Conjoined Health Regional Ethics Boards (CHREB) in Calgary and the Human Research Ethics Board in Edmonton. Urban residents at the University of Calgary completed a paper survey in an academic session during their orientation period in July 2015, and the rural residents completed the survey during an academic session one week later. At the University of Alberta, urban residents completed a paper survey during an academic session in the third month of residency while the rural residents completed an online survey collected during the first 7 months of residency using the REDCap29 electronic data capture tool hosted at the University of Calgary.

Instrument

A questionnaire was developed based on the list of 65 core procedures identified by the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC).9 The final questionnaire included 69 procedures as we split “sutures” and “biopsies” into subtypes. The questionnaire was reviewed by three family physicians, and then modified. For each item, residents were asked to respond about their procedural skill training and comfort levels at the time of graduation from medical school and not during residency. Residents indicated whether they had theoretical knowledge of the procedure (read about the procedure or received verbal instruction), if they had observed or assisted in performing the procedure (or received video instruction) and how many times the resident had performed the procedure on their own during medical school. Residents were also asked if they were planning to perform the procedure in their future practice. The residents rated their level of confidence for each procedure using a Likert-type scale (1=no confidence; 2=minimal confidence; 3=can do it, if supervised; 4=can perform it independently; 5=can teach the procedure to others).

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 22.0, released 2013, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, 914-499-1900). Descriptive statistics were used to report age and gender and breakdown of respondents by place of medical school training (Canada or outside Canada). The numbers and percentages of residents who had observed or performed the procedures, level of confidence and future plans to perform the procedure were tabulated. The procedures that were performed more and less frequently, as well as resident’s self-reported confidence level, were analyzed by gender and program track (urban or rural). We grouped some response options for ease of analysis. The frequency of performance was grouped as none, few (1 to 4 times), and many (≥5 times). Similarly, confidence levels were grouped as no confidence (1), little confidence (2-3), and high confidence (4-5). Chi-square testing was used to compare proportions and study the relationship between dichotomous and categorical variables. We performed these tests for each procedure. For comparisons of average number of procedures residents performed and plan to practice, between groups of residents (gender and program track), we performed independent t-tests and Brown-Forsythe tests of means when the homogeneity of variances assumption required for the t-test was not met. Probability values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. We chose not to perform corrections for multiple comparisons as this is an exploration of potential differences between groups of residents.

A total of 146 early PGY1 residents to the two FM programs in Alberta in July 2015 completed the survey (response rate 82%). Of these, 92 (63%) were from the University of Calgary and 54 (37%) were from the University of Alberta; 123 residents (84%) were in the urban tracks, and 23 (16%) in the rural streams of the programs. Sixty-two (42%) respondents were male, 78 (53%) were female, and 6 (4%) chose not to disclose. Canadian graduates (CMGs) accounted for 133 (91%) residents, and 13 (9%) were international graduates (IMGs). Table 1 summarizes further characteristics of the participants by each residency program.

Sixty-nine medical procedures were evaluated in this survey. The proportions of residents who reported having observed and/or assisted in performing each procedure during medical school, previous performance, and plan to practice specific procedures during independent practice are shown in Table 2. Of the 69 procedures, 15 (21.7%) had been previously performed at least five times by at least 50% of the residents. Only five procedures were rated by 80% or more of the residents as “being able to perform independently or to teach to others”: simple suture, infiltration of local anesthetic, intramuscular injection, cryotherapy of skin lesions and Pap smear. More than half of the residents identified 16 procedures as “able to perform procedures independently or to teach them to others”. The mean number of procedures residents felt highly confident with (“can perform independently or can teach to others”) was not statistically different between males (21.65±11.14) and females (18.56±9.07). Rural residents felt confident with more procedures (27.39±8.28 for rural, 18.53±9.78 for urban; P<0.001; Table 3). Female residents were more confident than males only in performing Pap tests (P<0.01; Table 4), while male residents were more confident with 10 procedures: wound debridement, shave biopsy, digital block, instilling fluorescein, removal of foreign body from cornea or conjunctiva, removal of foreign body from nose, reduction of dislocated radial head, reduction of dislocated shoulder, endotracheal intubation, and infant peripheral venous access (P values < 0.05).

No significant difference was found for the mean number of procedures incoming male (53.61±10.74) and female (50.72±12.83) residents were planning to perform in their future independent practice (Table 3). However, more female residents than male residents indicated intention to perform diaphragm fitting insertion and endometrial biopsy (P values <0.05). More male residents than female residents reported intention to perform eight procedures: release of subungual hematoma, reduction of dislocated shoulder, removal of corneal or conjunctiva foreign body, pare skin callus, bag and mask ventilation, cardiac defibrillation, venipuncture and peripheral intravenous line placement for adults (P values<0.05, Table 4).

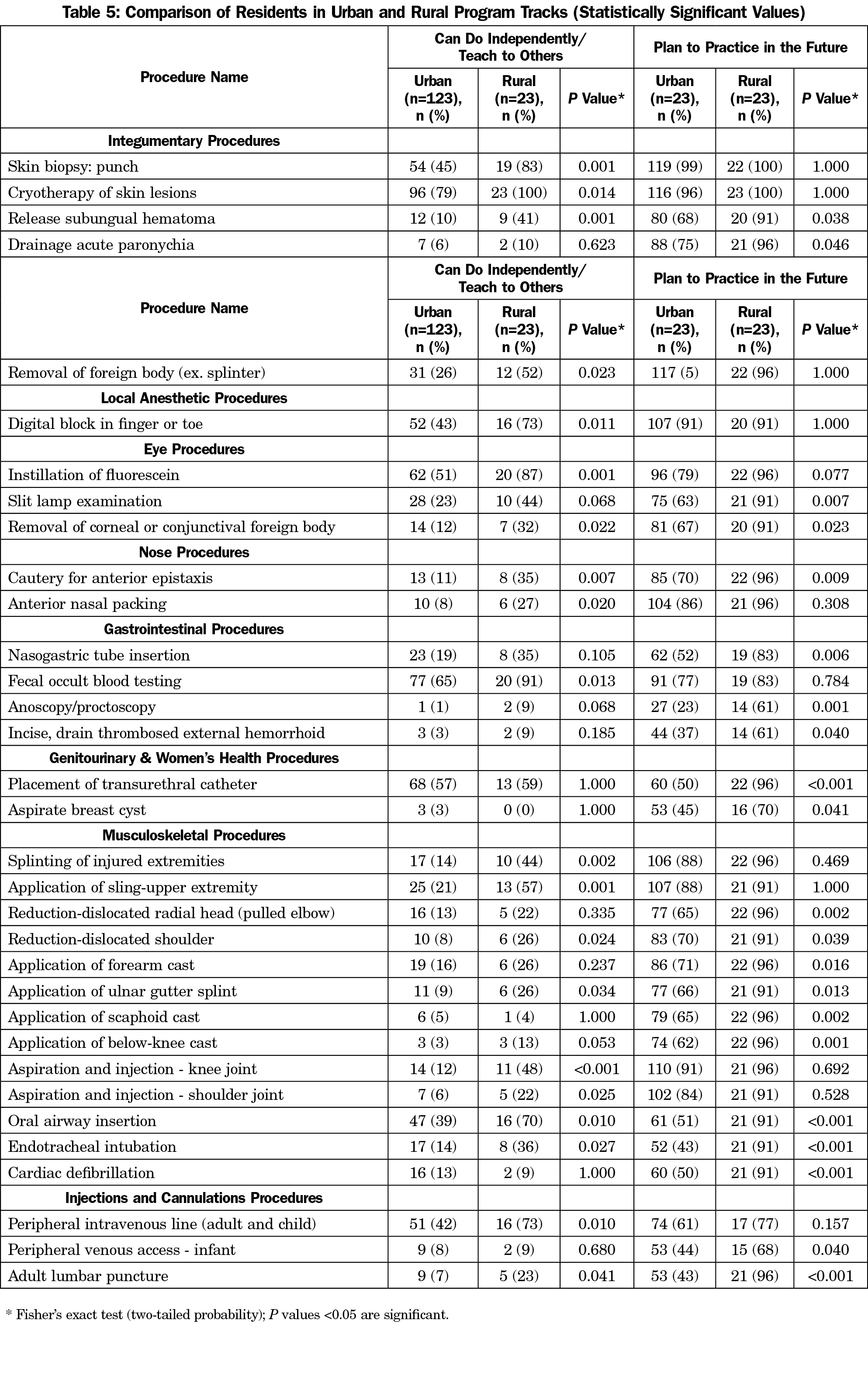

When analyzed independently, a larger proportion of incoming rural residents reported they were confident in 21 procedures than their urban colleagues (Table 5). Incoming rural residents also indicated that they plan to practice more procedures in the future than did their urban resident colleagues (mean 59.91 vs 50.23, P<0.001, Table 3). There were 22 procedures that incoming rural residents were more likely to intend to include in their future practice (P values < 0.05, Table 5). These included the resuscitation procedures: oral airway insertion, bag-and-mask ventilation, endotracheal intubation and cardiac defibrillation.

Residency programs traditionally assume that incoming residents have had some training in common procedures before residency,15 however, only a small fraction (15 out of 69) of the surveyed procedures had been performed more than five times by at least half of the incoming residents. Furthermore, the majority of incoming resident had high levels of confidence for only five procedures. Compared to incoming urban program residents, incoming rural program residents reported having more procedural training, and feeling more confident to perform a larger array of procedures. Further, incoming rural residents reported planning to perform more procedures in their future practice than did their urban counterparts. Male residents reported a higher level of confidence than did female residents, and expected to perform more procedures, except for specific gynecological procedures.

Previous studies have shown that incoming residents’ self-reported lack of experience performing procedures contrasts with the level that is expected by program directors of residents entering FM residency programs.16 The low number of skills that residents in our study are confident to independently perform, especially those training at urban-based residency programs, suggests these incoming residents will require additional training for the majority of core procedures to achieve sufficient levels of confidence and proficiency.11-12 while residents with previous experience can benefit from higher-level instruction to mastery level.13 Our study also suggests that family medicine programs need to evaluate the procedural skills competencies of each incoming resident. Incoming residents who have had less exposure to procedural training will need more comprehensive education during their residency training.

Previous data about medical students entering family medicine programs in Ontario in 2006 showed no difference in procedural training between residents starting training in urban or rural streams of the program.27 Our contrasting finding may be attributed to the recent differentiation of rural tracks, through efforts of several programs in Canada to expose students to more rural rotations or assigning a substantial part of their training in rural settings, for example Rural Longitudinal Integrated Community Clerkships,30 where students spend 9 months of their training in a specific rural location.

The finding that incoming rural residents plan to perform more procedures in the future compared with urban residents is similar to earlier findings in the literature.25,26 This could be attributed to previous exposure to rural training, but also to incoming rural residents seeking such procedural training during medical school due to knowing what is required for such practice from their rural origin, or personal motivation.

Previous studies24 found similar differences in procedural experience between genders. Specific training and motivational opportunities should be offered to female residents to learn and gain comfort with a wide variety of procedures. Male residents may need more practice in gynecological procedures.

Just over half of the surveyed residents had attended medical school in Alberta. The remaining residents who responded to the survey had attended a variety of medical schools across Canada, and a few were international medical graduates. Given the great variation of represented medical schools, there were too few residents from each medical school to perform meaningful comparative analysis.

As FM residency training in Canada provides only 2 years to learn a large number of procedures, these results demonstrate the need for programs to develop efficient approaches for such training. This implies a pedagogical framework and careful schedule of activities1,31,32 prioritized on community needs, resident preference, and intentions to practice. Teaching interventions such as providing reading materials, online instructional modules, video training, and classroom teaching can reinforce the cognitive component of training.33-37 Structured simulation workshops, procedure clinics, and selected procedural rotations in surgical services can provide psychomotor skills.31,38,39 Finally, activities combining standardized patient and simulators can reinforce the patient-centered approach to undertaking procedures.40

Limitations

The data obtained from residents were self-reported, and it is possible that participants could have erred in their estimates of the number of procedures performed and/or their confidence to perform these procedures independently. We were unable to include validation or reliability assessment. Data collection from residents in the rural tracks of the programs occurred later than from urban residents. This difference could have affected the perception of confidence and the exposure to procedures among the rural residents at the University of Alberta, although the residents were specifically asked to rate the levels before residency. Furthermore, the response rate from rural residents was much lower than from urban residents, increasing the possibility of a response bias. The residents could have become fatigued with the long questionnaire and the responses at the end of the survey could have become more arbitrary. The statistical tests per procedure were meant to highlight the procedures in which groups may have potential differences. As we conducted the tests multiple times, some statistically significant results we found may have occurred by chance.

Family medicine residency programs can benefit from information concerning the knowledge and levels of skill training in procedures that residents bring into residency. This data can provide a basis for curricular design, guide implementation of teaching activities and assist allocation of resources. Limited prior procedural skills training and performance among incoming residents highlight the need for FM programs to develop teaching interventions to help each resident achieve competence in skills necessary for practice.

References

- Grantcharov TP, Reznick RK. Teaching procedural skills. BMJ. 2008;336(7653):1129-1131.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39517.686956.47.

- Kovacs G. Procedural skills in medicine: linking theory to practice. J Emerg Med. 1997;15(3):387-391.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0736-4679(97)00019-X.

- Sanders CW, Edwards JC, Burdenski TK. A survey of basic technical skills of medical students. Acad Med. 2004;79(9):873-875.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200409000-00013.

- Crutcher RA, Szafran O, Woloschuk W, et al. Where Canadian family physicians learn procedural skills. Fam Med. 2005;37(7):491-495.

- Nelson MS, Traub S. Clinical skills training of U.S. medical students. Acad Med. 1993;68(12):926-928.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199312000-00015.

- van der Vlugt TM, Harter PM. Teaching procedural skills to medical students: one institution’s experience with an emergency procedures course. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;40(1):41-49.

https://doi.org/10.1067/mem.2002.125613.

- Margolick J, Kanters D, Cameron BH. Procedural skills training for Canadian medical students participating in international electives. Can Med Educ J. 2015;6(1):e23-e33.

- O’Connor HM. Training undergraduate medical students in procedural skills. Emerg Med (Fremantle). 2002;14(2):131-135.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1442-2026.2002.00333.x.

- College of Family Physicians of Canada. Defining competence for the purposes of certification by the College of Family Physicians of Canada: the evaluation objectives in family medicine. Report of the Working Group on the Certification Process. Part II—The evaluation objectives for daily use: the operational level, for assessing competence. Procedure Skills. October 2010. http://www.cfpc.ca/uploadedFiles/Education/Certification_in_Family_Medicine_Examination/Definition%20of%20Competence%20Complete%20Document%20with%20skills%20and%20phases.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2016.

- Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors. CAFM consensus for procedural training in family medicine residency. http://m.afmrd.org/files/CAFM%20guidelines%20documents/CAFMProceduralTraininginGuideline_1.pdf. Accessed September 20,2016

- Sylvester S, Magin P, Sweeney K, Morgan S, Henderson K. Procedural skills in general practice vocational training - what should be taught? Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40(1-2):50-54.

- Nothnagle M, Sicilia JM, Forman S, et al; STFM Group on Hospital Medicine and Procedural Training. Required procedural training in family medicine residency: a consensus statement. Fam Med. 2008;40(4):248-252.

- Kelly BF, Sicilia JM, Forman S, Ellert W, Nothnagle M. Advanced procedural training in family medicine: a group consensus statement. Fam Med. 2009;41(6):398-404.

- Dent JA, Harden RM, eds. A Practical Guide for Medical Teachers. 3rd ed. London: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2009.

- Ladak A, Hanson J, de Gara CJ. What procedures are students doing during undergraduate surgical clerkship? Can J Surg. 2006;49(5):329-334.

- Dickson GM, Chesser AK, Woods NK, Krug NR, Kellerman RD. Family medicine residency program director expectations of procedural skills of medical school graduates. Fam Med. 2013;45(6):392-399.

- Fitch MT, Kearns S, Manthey DE. Faculty physicians and new physicians disagree about which procedures are essential to learn in medical school. Med Teach. 2009;31(4):342-347.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590802520964.

- Langdale LA, Schaad D, Wipf J, Marshall S, Vontver L, Scott CS. Preparing graduates for the first year of residency: are medical schools meeting the need? Acad Med. 2003;78(1):39-44.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200301000-00009.

- Lyss-Lerman P, Teherani A, Aagaard E, Loeser H, Cooke M, Harper GM. What training is needed in the fourth year of medical school? Views of residency program directors. Acad Med. 2009;84(7):823-829.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a82426.

- Promes SB, Chudgar SM, Grochowski CO, et al. Gaps in procedural experience and competency in medical school graduates. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(suppl 2):S58-S62.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00600.x.

- Gazibara T, Nurković S, Marić G, et al. Ready to work or not quite? Self-perception of practical skills among medical students from Serbia ahead of graduation. Croat Med J. 2015;56(4):375-382.

https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2015.56.375.

- Dickson GM, Chesser AK, Keene Woods N, Krug NR, Kellerman RD. Self-reported ability to perform procedures: a comparison of allopathic and international medical school graduates. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(1):28-34.

https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2013.01.120124.

- Tucker W, Diaz V, Carek PJ, Geesey ME. Influence of residency training on procedures performed by South Carolina family medicine graduates. Fam Med. 2007;39(10):724-729.

- Chaytors RG, Szafran O, Crutcher RA. Rural-urban and gender differences in procedures performed by family practice residency graduates. Fam Med. 2001;33(10):766-771.

- Wetmore SJ, Agbayani R, Bass MJ. Procedures in ambulatory care. Which family physicians do what in southwestern Ontario? Can Fam Physician. 1998;44:521-529.

- Wetmore SJ, Rivet C, Tepper J, Tatemichi S, Donoff M, Rainsberry P. Defining core procedure skills for Canadian family medicine training. Can Fam Physician. 2005;51:1364-1365.

- Goertzen J. Learning procedural skills in family medicine residency: comparison of rural and urban programs. Can Fam Physician. 2006;52:622-623.

- Connick RM1, Connick P, Klotsas AE, et al. Procedural confidence in hospital based practitioners: implications for the training and practice of doctors at all grades. BMC Med Educ. 2009;12:9:2.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

- University of Calgary, Cumming School of Medicine. University of Calgary Longitudinal Integrated Clerkship (UCLIC). Undergraduate Medical Education. Core Document. Class of 2017. http://www.ucalgary.ca/mdprogram/files/mdprogram/uclic_coredoc_cl2017.pdf. Accessed February 27, 2017.

- Garcia-Rodriguez JA. Filling the gaps between theory and daily clinical procedural skills training in family medicine. Educ Prim Care. 2016;27(3):172-176.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2016.1169443.

- Sawyer T, White M, Zaveri P, et al. Learn, see, practice, prove, do, maintain: an evidence-based pedagogical framework for procedural skill training in medicine. Acad Med. 2015;90(8):1025-1033.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000734.

- Lee JC, Boyd R, Stuart P. Randomized controlled trial of an instructional DVD for clinical skills teaching. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19(3):241-245.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-6723.2007.00976.x.

- Summers AN, Rinehart GC, Simpson D, Redlich PN. Acquisition of surgical skills: a randomized trial of didactic, videotape, and computer-based training. Surgery. 1999;126(2):330-336.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0039-6060(99)70173-X.

- Garcia-Rodriguez JA, Donnon T. Using comprehensive video-module instruction as an alternative approach for teaching IUD insertion. Fam Med. 2016;48(1):15-20.

- Xeroulis GJ, Park J, Moulton CA, Reznick RK, Leblanc V, Dubrowski A. Teaching suturing and knot-tying skills to medical students: a randomized controlled study comparing computer-based video instruction and (concurrent and summary) expert feedback. Surgery. 2007;141(4):442-449.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2006.09.012.

- Nousiainen M, Brydges R, Backstein D, Dubrowski A. Comparison of expert instruction and computer-based video training in teaching fundamental surgical skills to medical students. Surgery. 2008;143(4):539-544.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2007.10.022.

- Sierpina VS, Volk RJ. Teaching outpatient procedures: most common settings, evaluation methods, and training barriers in family practice residencies. Fam Med. 1998;30(6):421-423.

- Garcia-Rodriguez JA. Teaching medical procedures at your workplace. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(4):351-354, e222-e225.

- Kneebone R, Kidd J, Nestel D, Asvall S, Paraskeva P, Darzi A. An innovative model for teaching and learning clinical procedures. Med Educ. 2002;36(7):628-634.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01261.x.

There are no comments for this article.