Background and Objectives: General competencies developed in undergraduate and graduate medical education are sometimes promoted as applicable in any practice context. However, rural practice presents challenges and opportunities that may require unique training. The objectives of this national survey of both undergraduate and graduate medical educators and practicing physicians were to further develop a previously published list of competency domains for working in rural communities and to assess their relative importance in education and practice.

Methods: Using six rural competency domains first refined with a national group at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Meeting in Baltimore in 2008, the authors employed a snowball strategy to survey medical educators and physicians regarding the importance and relevance of this list and to solicit additional domains and competencies.

Results: All six domains were considered important, with average responses for each domain ranging from 4.16 to 4.78 on a 5-point Likert scale (1-not important; 5-extremely important). Unique relevance to rural practice was more varied, with average responses for domains ranging from 2.36 to 3.6 (1-not at all unique; 5-extremely unique). Analysis of free text responses identified two important new domains—Comprehensiveness and Agency/Courage—and provided clarification of some competencies within existing domains.

Conclusions: This study validates and further elaborates dimensions of competence believed to be important in rural practice. The authors propose these domains as a common language and framework for addressing the unique challenges and opportunities that training and practicing in a rural setting present.

For decades, medical educators, including those in family medicine, have widely embraced competency-based education.1,2 In the United States, a number of general competencies in both undergraduate and graduate medical education and training are incorporated into standards for accreditation.3-5 Even before admission to medical school, the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) recommends applicants be assessed on 15 competencies in four domains.6 Educators in other countries have developed their own sets of competencies with different competency frameworks.7,8 The Physician Competency Reference Set (PCRS), a unifying framework of 58 competencies across eight competency domains, seeks to bring these many lists together into a coherent framework and to provide a standardized taxonomy of outcomes defining general physician competence.9

As we embrace competency-based education, questions of context arise around geography, caring for special populations, regionalization of medical education and clinical training sites, and the meaning of competence in the setting of teams.10,11 Unfortunately, much of the medical education community in the United States, as in Canada, follows “a nationally-based approach...in a way that [attempts to ensure] equity of experience no matter where the clinical teaching site learners are training.”12 Such an approach is potentially agnostic of place and could diminish the role of context.

Leaders in the competency-based education movement explicitly assert that competence in practice is fundamentally contextual. Competence has been defined as “The array of abilities…across multiple domains or aspects of performance in a certain context” (emphasis added).2 The original authors of the PCRS framework suggest that context could be integrated into to their list of competencies by adding qualifiers.9 Ekstrand et al, for example, have done this, approaching a subpopulation by adding 30 content and context-specific qualifiers to 20 of the 58 total competencies.10

Given the unique context of practice in a rural community, it stands to reason that there might be a list of domains and competencies that are particularly important to sustained competence in that geographic setting. Physicians wishing to practice in low-resource or underserved rural communities will eventually face challenges that may require additional knowledge, skills, attitudes, values, and other professional attributes.

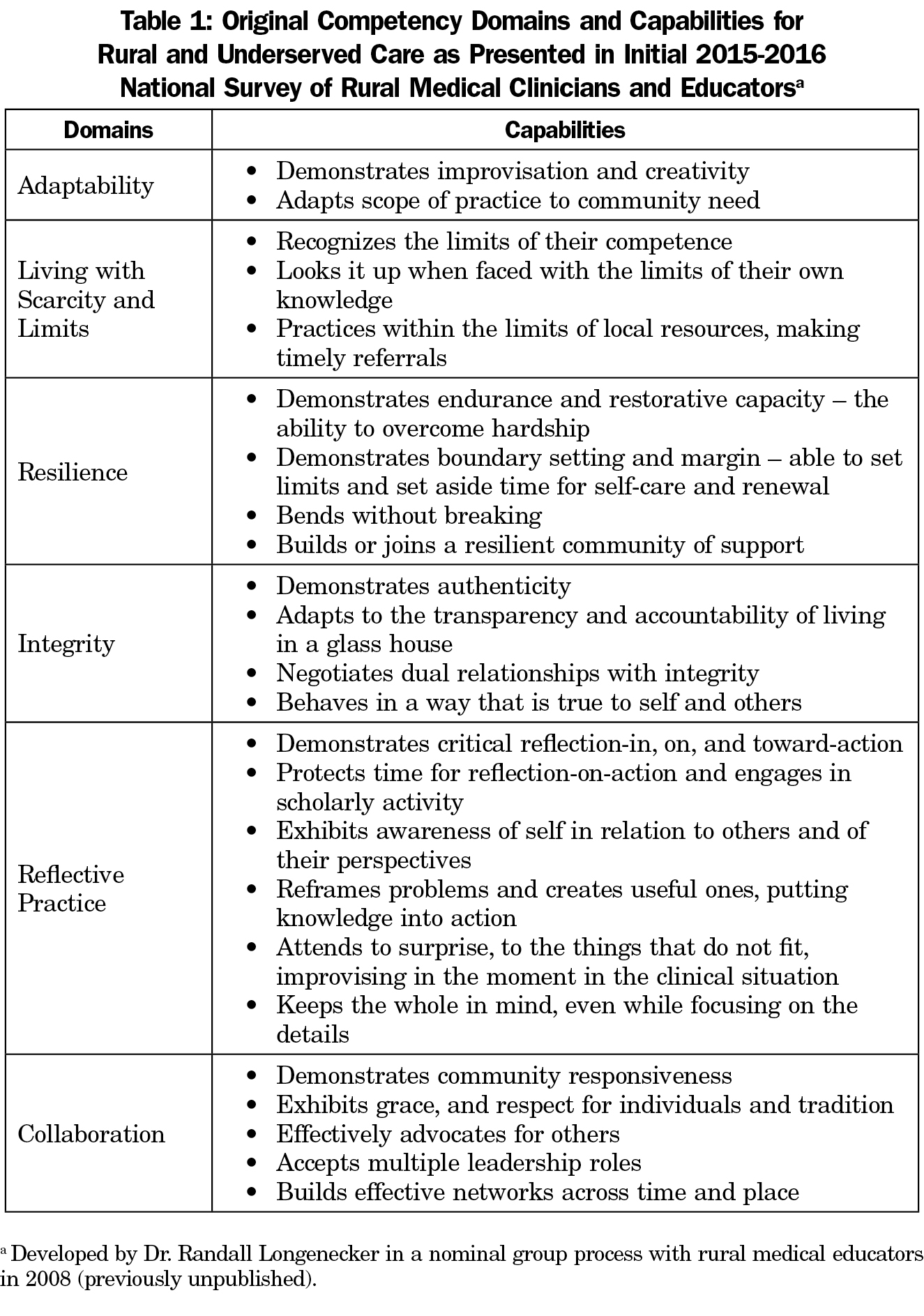

Over the past 2 decades, work has been done by individuals in social work, nursing, and medicine to define what those rural competencies might be.13,14 Specifically, national groups representing rural and remote medicine in Australia and Canada have defined contextual and clinical competencies for rural physicians, but there has been no comprehensive contribution to this literature from the United States.12,15 In 2008, a group of rural medical educators met at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) Spring Conference in Baltimore to address this task. A list of domains and competencies had been proposed in 2007 by the lead author, who as a program director had earlier constructed this list for use in a rural training track residency program. Several rural medical educators attending the STFM Spring Conference, and subsequently additional members of the STFM Group on Rural Health, expanded and then refined the list through an iterative group process.16 This included the generation of additional domains and competencies through email interaction before the conference, a nominal group ranking and clustering at the conference, and a subsequent round of refining and clustering that occurred with a larger group online in the weeks following the conference (Table 1). In 2008, and again in 2013, the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and the National Rural Health Association (NRHA) recommended in a joint position paper that the competencies be implemented more widely.17,18 In the years since, these competencies have been communicated and implemented in various ways and in multiple versions in medical school and residency programs across the United States, and internationally.19-21 The objective of this study, a national survey of both undergraduate and graduate medical educators and practicing physicians (many but not all of whom are family physicians), was to further develop a comprehensive list of competencies for rural practice and to assess the relative importance of these domains in education and practice.

Using the domains and competencies for rural practice that were initially developed through the process described above, we employed a snowball strategy to survey medical educators and physicians regarding the importance and relevance of the domains for rural practice, and to solicit additional domains and competencies and develop a more complete and useful list.

We developed a survey describing each proposed rural competency domain. See Table 1 for descriptions of the six rural competency domains included in the initial survey. We left it to each participant to define “rural” from their own perspective, since there is no universally accepted definition. After completing demographic information, we asked participants to rank each domain according to its importance and its unique relevance to rural and underserved practice, using a Likert scale of 1 to 5 ranging from “not at all important (or unique)” to “extremely important (or unique).” Without imposing a character or word limit, we also asked participants to free text any specific domains or capabilities that were relevant to rural or underserved practice but were not included on the initial list.

We sent an invitation for the initial survey as an anonymous Qualtrics version 2016 (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) survey link in November 2015 via email to members of the listservs of the STFM Group on Rural Health, the RTT (rural training track) Collaborative, NRHA Rural Medical Educators Group, AAFP Rural Health Member Interest Group, and the DR-ED email list, an electronic discussion group for medical educators sponsored by the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, Office of Medical Education Research and Development. These groups were chosen because their constituents included rural physicians and medical educators. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and snowball sampling was encouraged by asking participants to forward the invitation to others potentially interested in rural medical education. We also distributed the survey link to attendees of national conferences relevant to rural medical education held in the spring of 2016, including STFM, NRHA, AAFP Program Directors Workshop, and the International Community Engaged Medical Education Network Conference.

We summarized demographic characteristics using descriptive statistics. We converted participant responses to the questions of whether existing domains were important or uniquely relevant to rural medical education to a numerical scale, and comparatively ranked them according to participants’ impression of importance and relevance. Statistical comparisons were accomplished using SPSS Version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY).

Three researchers coded free text quotes and grouped the codes into themes to identify incomplete or missing competency domains. Once all quotes were coded and themes were established, we analyzed and compared them to existing competency domains to determine whether participant suggestions were included in the original competencies (possibly requiring rewording for clarification), whether suggestions were indeed additional capabilities that should be included under existing domains, or whether suggestions were new domains not described in the initial survey.

Since we did uncover new domains upon analysis of the initial survey, we redrafted and described the competencies in a second survey that was sent to the NRHA Rural Medical Educators and the AAFP Rural Health Member Interest Group in August 2016.

This project was granted ethical approval by the Ohio University Institutional Review Board.

The initial survey invitation link was opened by 174 individuals; of those that opened the link, 171 participated in the survey and 146 completed at least 70% of the seven survey questions. Survey results are based on the responses of 171 participants.

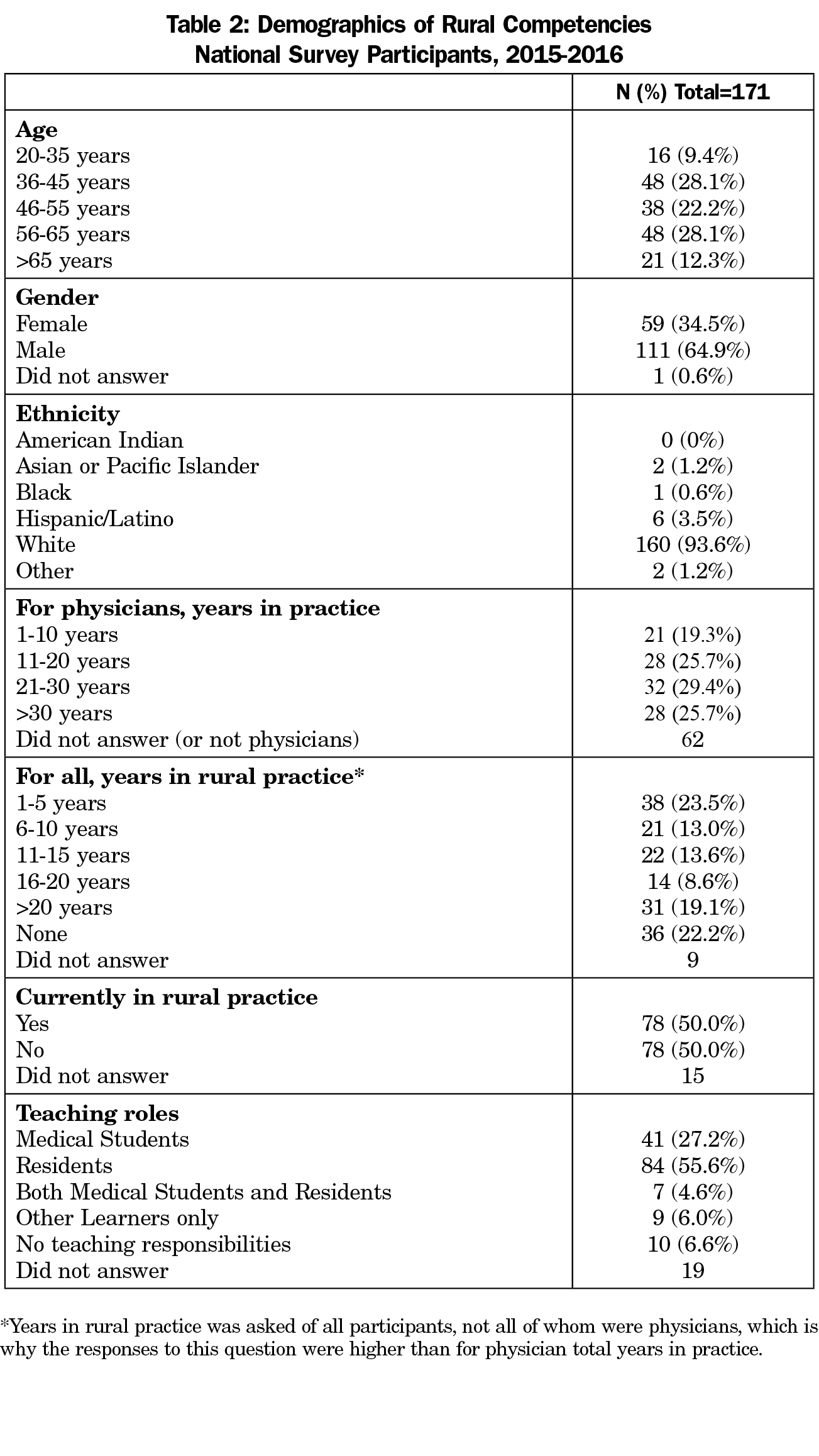

Self-reported demographics of survey participants are presented in Table 2. Most survey participants were male (n=111; 64.9%), white (n=160; 93.6%), and had at least some experience practicing in a rural community (n=131; 78%). About half of respondents (n=78; 50%) were currently in rural practice. The majority of respondents (n=132; 87.4%) taught residents, medical students, or both.

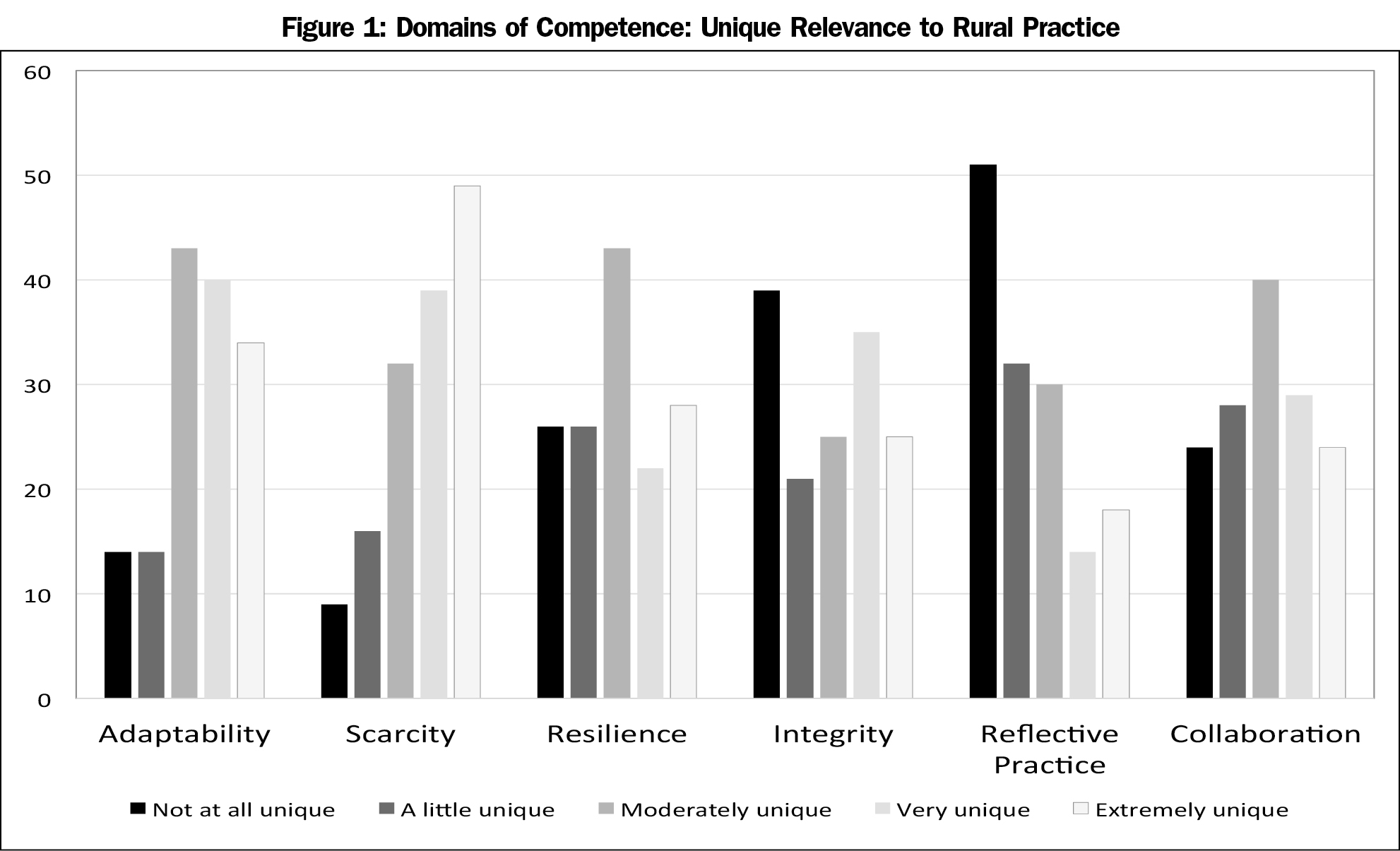

The survey asked respondents to rank the importance and the relevance of each curricular domain for rural practice. All six domains were considered important, with average responses for each domain ranging from 4.16 to 4.78 on a 5-point Likert scale (1-not important; 5-extremely important). Unique relevance to rural practice was more varied, with average responses for domains ranging from 2.36 to 3.6 (1-not at all unique; 5-extremely unique; see Figure 1). Of the six domains, “Reflective Practice” was considered the least unique to rural practice and “Living with Scarcity and Limits” the most unique. There were no statistically significant differences seen when we compared responses based on participant’s age, gender, current rural practice, or rural practice experience.

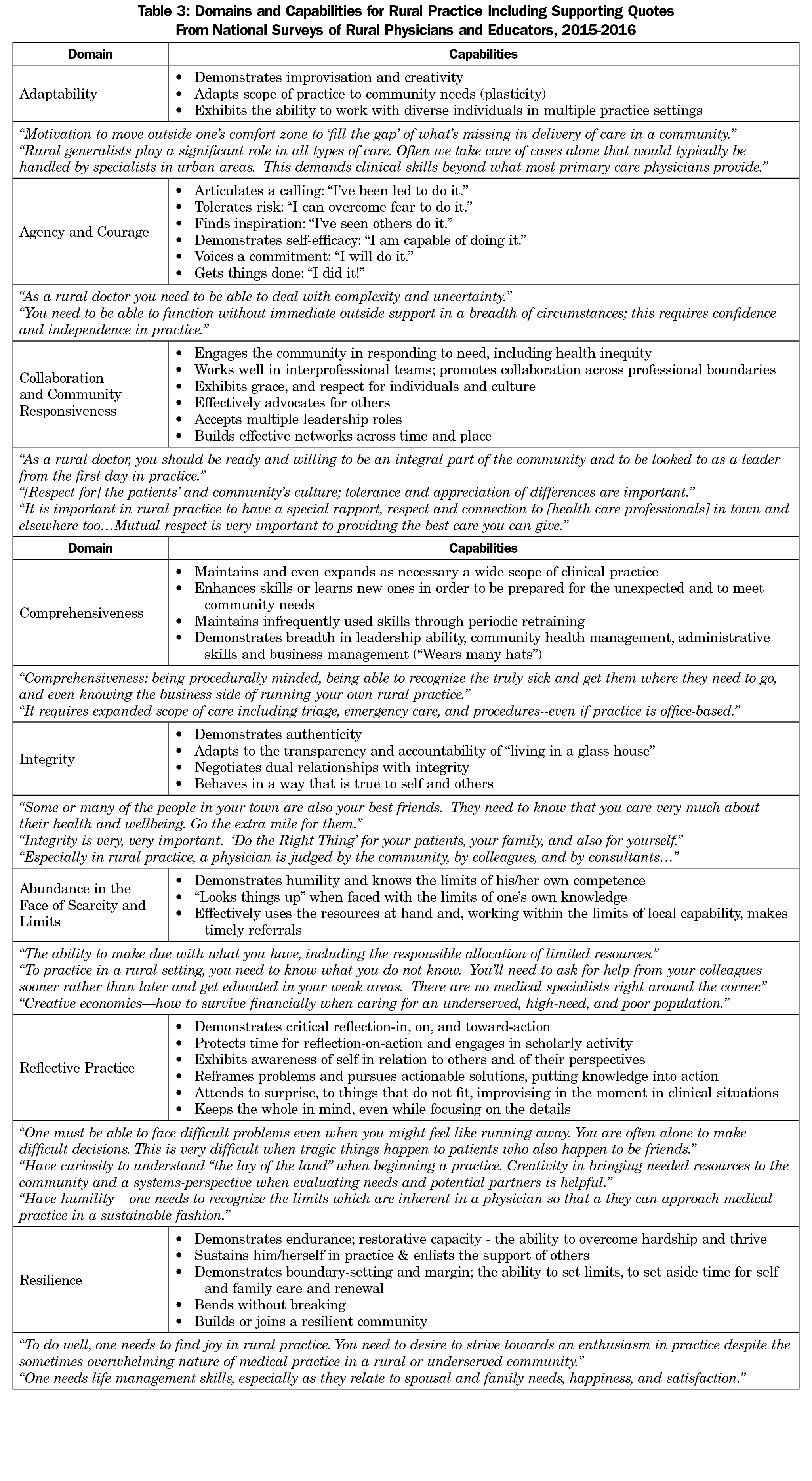

Analysis of free text responses to the question “What important or uniquely relevant competencies are missing from these domains?” resulted in the addition of two important new domains—Comprehensiveness and Agency/Courage—as well as clarification of some competencies within existing domains. For example, several respondents suggested framing “Living with Scarcity and Limits” in a more positive way, and this domain was renamed “Abundance in the Face of Scarcity and Limits.” The final model of domains and competencies for rural practice, incorporating changes uncovered by the national survey and with supporting quotes for each domain, is presented in Table 3.

We sent a final survey to the NRHA Rural Medical Educators Group and the AAFP Rural Health Member Interest Group. This survey described this revised and final list of domains and competencies for rural practice and requested input into whether there were any domains or competencies that were unclear or missing. The survey was returned by 16 participants (9 male [56%]; 100% Caucasian; 15 with rural practice experience [93%]; 15 with teaching duties, [93%]; and 10 currently practicing rurally, [60%]). No additional domains or competencies were uncovered by this follow-up survey.

This study lends validity to and further elaborates dimensions of competence believed by a convenience sample of medical educators to be particularly important in rural practice. However, there was no consensus as to their unique relevance to rural medicine, which may reflect the importance of such competencies to other practice settings as well. We do not feel this finding detracts from their relevance, but rather, as one respondent mused, it may be in the rural context that these domains of competence are most appreciated and where they are most apparent in their absence, possibly due to the lack of redundancy in a low-resource or remote practice setting:

I think the idea that you can teach such competencies or check them off a list when done, reminds me of Benjamin Franklin’s project as a youth to build his character, designating a week each for one of the virtues, after which he would be “done”. I think a rural physician is akin to the adage about pilots: Flying is not dangerous. It’s just less forgiving of mistakes. A really good physician should be all of the things you listed, and then some, but this is true for all physicians. For rural physicians, however, the price of deficiencies is much higher.

Competence is multidimensional (ie, multiple domains in multiple dimensions), multifaceted (from multiple perspectives, that of the individual and those of others), and dynamic (changing with time, experience and setting).9 Yet in much of the clinical and medical education literature, competence has often been reduced to a checklist of behaviors. By grappling with the definition of competence in the rural context and implementing the competency domains proposed a decade ago in rural undergraduate and graduate medical education, we as authors have come to understand competence in a less conventional way. Like others, we question the completeness and relevance of current models of competence, especially in the authentic context of rural practice, and suggest these domains be used differently.22

As suggested by several survey respondents and affirmed in our interactions with family medicine and other educators during presentations of our research, achieving and sustaining intrinsic competence is more than a technical or developmental task.23,24 These domains are interrelated, and although difficult to measure or sum in parts, are relatively easily recognized in the whole in practice. Like the general competency domain of professionalism, these rural domains defy a reductionist approach that addresses competence only as a cumulative list of capabilities. And also like professionalism, it may be better not to deconstruct them.

Just as virtues complement a principle-based approach to ethics, the rural domains described in this study may best be used in rural education and training to complement (rather than further complicate) the conventional competency-based approach.25,26,27 The rural domains may best serve as beacons in learning and practice, cultivating character-building habits in ourselves and, through modeling, in learners as well as peers.24 Good rural physicians will commit to becoming more and more competent in these domains, continually realigning their own behavior and moving toward an aspirational goal they may never fully reach. This will require continuous reflection and lifelong learning.

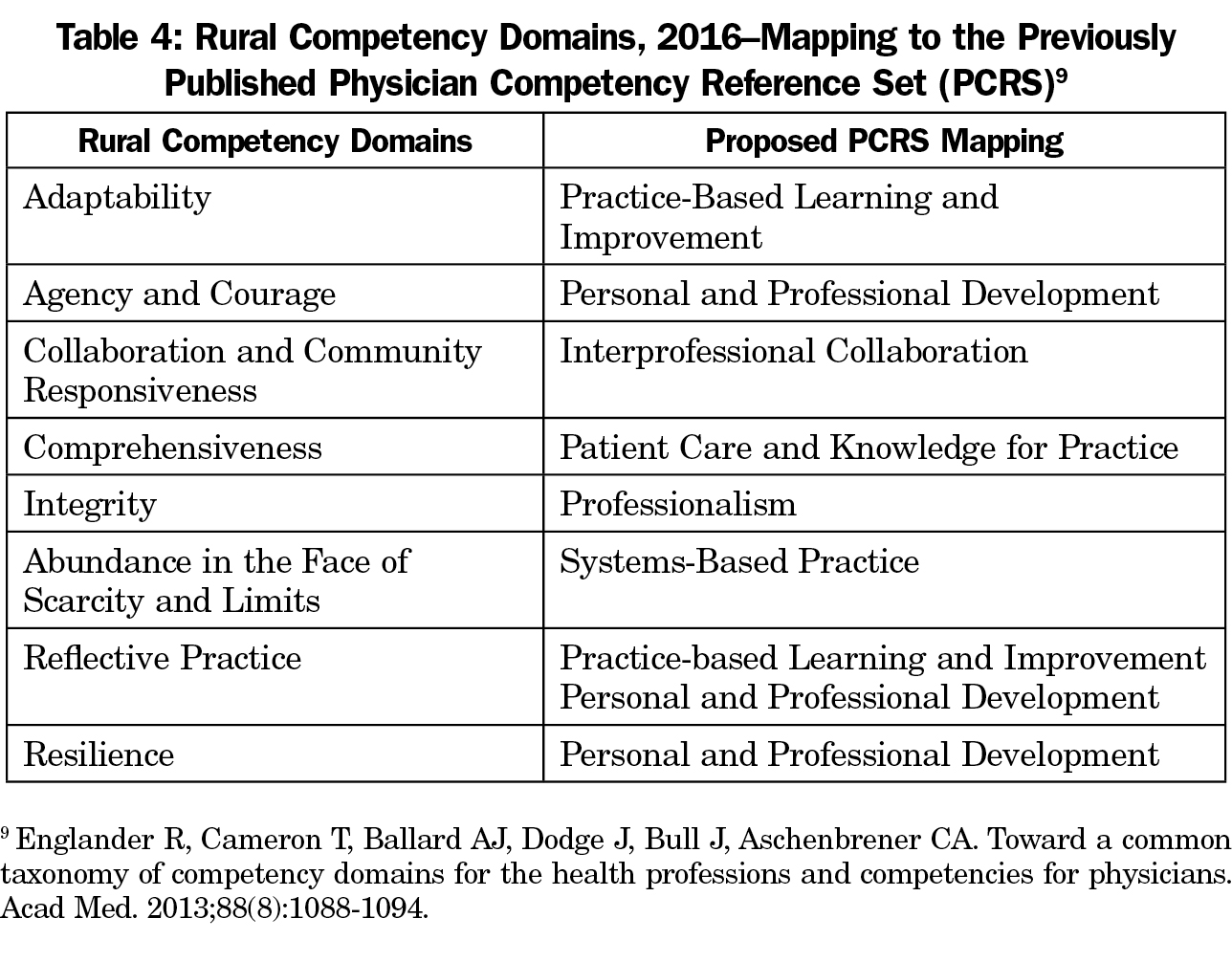

We propose the domains of competence further refined in this study as a common language and framework for addressing the important challenges and opportunities presented by training and practicing in a rural setting. Rather than reducing them to a checklist and burdening those who teach with yet more documentation, we propose these domains serve as curricular anchors, bringing geographic context to the general competencies to which they can be mapped. These rural domains, applicable across multiple general competencies, add particularly important dimensions to some of them and map to the Physician Competency Reference Set (PCRS) in complementary ways (See Table 4).9

We suggest that medical educators use the competency domains for program and curricular design, even programmatic mapping and evaluation, fostering the deliberate development of these habits in our learners and developing reflective measures for self-monitoring over the course of their careers. Teaching toward these competencies may, in a formative way, help our learners set aspirational goals. Always keeping the end in mind, faculty can ask learners to identify the competency domains they believe a given learning activity addresses and ask how they intend to change their own practice following the activity. As an educational tool, case examples for each domain are provided in the STFM Resource Library (https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/competencies-for-rural-and-underser?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a). Medical educators can develop workshops intended to build resilience, comprehensiveness, or agency and courage, and then as an assessment of program effectiveness—rather than as a measure of an individual’s capability—look for evidence of genuine understanding in the learners’ reflections and verbatims.17

This study has several limitations. The survey respondents were a convenience sample and may not have been representative of all rural practitioners or rural medical educators. Although designed to target rural physicians and educators, this study captured some respondents without rural practice experience, which we considered both a limitation and an opportunity. Rather than excluding these participants, we opted to include all responses in the analysis and no significant differences were found between respondents based on rural practice experience. The number of responses to the validation survey was small and this work deserves more rigorous validation. Further work should explore whether these domains and competencies are also relevant to other underserved practice settings such as urban underserved communities or global mission settings.

We struggled with defining “rural” for this study as there are currently many federal definitions.28 We chose not to explicitly define rural in the survey, but rather leave this to the participants’ perspectives, which may have affected responses. This is a limitation of this study, but it is also an ongoing challenge for the discipline. Although no one definition is likely to be universally applicable, developing a shared operational definition of rural for the purpose of health professions education research would be an important advance.

The process by which this list of domains and competencies was originally developed (eg, lack of an a priori and intentional design) does not yet warrant use of the term “consensus” to describe the list that was produced.29 A consensus is still emerging, beginning with an intentional nominal group process almost a decade ago, then proceeding serendipitously among a panel of experts in their use, and now, in this study, clarified through an iterative national survey and series of workshops and focus groups. A formal consensus as to the explicit role of these domains in medical education for rural practice and their relationship to the Physician Competency Reference Set awaits a formal consensus building process and another publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the medical educators who participated in this survey and those who contributed in each of the workshops at which this material was presented.

Previous Presentations:

Longenecker R, Hollander-Rodriguez J, Schmitz D. Competencies for rural and underserved practice, a workshop and research presentation, AFMRD Program Directors Workshop, Kansas City, MO, April 1 & 2, 2016.

Longenecker R, Wendling A, Bowling J. Competencies for rural and underserved practice, a seminar and research presentation at STFM Annual Spring Conference, Minneapolis, MN, May 2, 2016.

Longenecker R. Competencies for rural practice, presented as a PeARLS session, International Community Engaged Medical Education Conference (ICEMEN 2016), Sault Ste Marie, Ontario, Canada, June 24, 2016.

References

- Bell HS, Kozakowski SM, Winter RO. Competency-based education in family practice. Fam Med. 1997;29(10):701-704.

- Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):638-645.

https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements effective July 1, 2016; IV.A.5. http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2016.

- American Osteopathic Association. American Osteopathic Association Basic Documents for Postdoctoral Training, July 2016; Section III. http://www.osteopathic.org/inside-aoa/accreditation/postdoctoral-training-approval/postdoctoral-training-standards/Documents/aoa-basic-document-for-postdoctoral-training.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2016.

- American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine. Osteopathic Core Competencies.

http://www.aacom.org/ome/profdev/occ. Accessed December 6, 2016.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. The 15 Core Competencies for Entering Medical Students endorsed by the AAMC Group on Student Affairs Committee on Admissions. https://www.aamc.org/admissions/dataandresearch/477182/corecompetencies.html. Accessed December 6, 2016.

- Frank JR, Danoff D. The CanMEDS initiative: implementing an outcomes-based framework of physician competencies. Med Teach. 2007;29(7):642-647.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701746983.

- Simpson JG, Furnace J, Crosby J, et al. The Scottish doctor--learning outcomes for the medical undergraduate in Scotland: a foundation for competent and reflective practitioners. Med Teach. 2002;24(2):136-143.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590220120713.

- Englander R, Cameron T, Ballard AJ, Dodge J, Bull J, Aschenbrener CA. Toward a common taxonomy of competency domains for the health professions and competencies for physicians. Acad Med. 2013;88(8):1088-1094.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829a3b2b.

- Eckstrand KL, Potter J, Bayer CR, Englander R. Giving context to the physician competency reference set: adapting to the needs of diverse populations. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):930-935.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001088.

- Lingard L. Rethinking competence in the context of teamwork. In: Hodges B, Lingard L, eds. The Question of Competence. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2012:42-69.

- Bosco C, Oandasan I. Review of Family Medicine Within Rural and Remote Canada: Education, Practice, and Policy. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2016.

- O’Sullivan D, Ross D, Young S. A framework for the use of competencies in rural social work field practice placements. Aust Soc Work. 1997;50(1):31-38.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03124079708415205.

- Hurme E. Competencies for nursing practice in a rural critical access hospital. Online J Rural Nurs Health Care. 2009;9(2):67-81.

- Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine. Primary Curriculum. 4th ed. http://www.acrrm.org.au/misc/curriculum/Default.htm. Accessed March 14, 2017.

- Dobbie A, Rhodes M, Tysinger JW, Freeman J. Using a modified nominal group technique as a curriculum evaluation tool. Fam Med. 2004;36(6):402-406.

- Longenecker, R. National Rural Health Association Policy Brief: Graduate Medical Education for Rural Practice. https://www.ruralhealthweb.org/getattachment/Advocate/Policy-Documents/Archive/GMEforRural2008-(1).pdf.aspx?lang=en-US. Published 2008. Accessed March 18, 2017.

- Schmitz D. Graduate medical education for rural practice: position paper jointly sponsored by NRHA and AAFP. http://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/medical_education_residency/program_directors/Reprint289A_Rural.pdf. Published July 2008. Revised November, 2013. Accessed December 6, 2016.

- Longenecker R, Zink T, Florence J. Teaching and learning resilience: building adaptive capacity for rural practice. A report and subsequent analysis of a workshop conducted at the Rural Medical Educators Conference, Savannah, Georgia, May 18, 2010. J Rural Health. 2012;28(2):122-127.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00376.x.

- Hollander-Rodriguez J, Montjoy H. Competencies for rural health: an overarching framework for training interprofessional learners. A workshop presentation at STFM Spring Conference; April 2015; Orlando, FL.

- Longenecker R. Refining the competencies for rural practice. A workshop presented at Rural WONCA 2015; April 16, 2015; Dubrovnik, Croatia.

- Ginsburg S, McIlroy J, Oulanova O, Eva K, Regehr G. Toward authentic clinical evaluation: pitfalls in the pursuit of competency. Acad Med. 2010;85(5):780-786.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d73fb6.

- Schon DA. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1983.

- Leach DC. Competence is a habit. JAMA. 2002;287(2):243-244.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.2.243.

- Eckles RE, Meslin EM, Gaffney M, Helft PR. Medical ethics education: where are we? Where should we be going? A review. Acad Med. 2005;80(12):1143-1152.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200512000-00020.

- Karches KE, Sulmasy DP. Justice, courage, and truthfulness: virtues that medical trainees can and must learn. Fam Med. 2016;48(7):511-516.

- Saultz J. Professional Virtue. Fam Med. 2016;48(7):509-510.

- US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Overview of Rural Classifications. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-classifications/ Updated November 17, 2016. Accessed May 30, 2017.

- Waggoner J, Carline JD, Durning SJ. Is there a consensus on consensus methodology? Descriptions and recommendations for future consensus research. Acad Med. 2016;91(5):663-668.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001092.

There are no comments for this article.