Background and Objectives: Improvement in population health has become a key goal of health systems and payers in the United States. Because 80% of health outcomes are driven by social determinants of health beyond medical care and health care access, such improvements require attention to factors outside of the conventional areas of expertise for clinicians. Yet primary care physicians often graduate from training programs with few skills in population and community health.

Methods: In 2011, the University of Wisconsin Department of Family Medicine began transformative work to become a Department of Family Medicine and Community Health (DFMCH). As part of this effort, educators in the department addressed deficiencies in its residency’s community and population health curriculum by implementing curricular change and faculty development. A set of guiding principles, “Three Community Health Responsibilities for Family Doctors,” was developed to provide background and structure to current and future work.

Results: An annual program evaluation survey was administered to faculty and residents between 2012 and 2016. Respondents reported a significant increase in their understanding of population and community health over the prior year in each year this was assessed (P<0.001).

Conclusions: Community and population health principles have become part of the fabric of the entire residency curriculum in the DFMCH. Faculty development was a key part of this work and will be integral to sustaining improvements.

Since the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) 2001 landmark report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” health systems, payers, and the public have given increasing attention to the need for improved population-level health outcomes in the United States. This shift has resulted in a gradual transformation in reimbursement structures toward value-based rather than volume-based payments. Yet approximately 80% of health outcomes are driven by factors outside the clinical care sector,1 such as racism and poverty, yielding disparities in education, employment, and housing. This tension between accountability and influence has begun to spur innovation as hospitals, insurers, and practice groups seek approaches to improving community and population health that extend beyond the usual clinical activities.2

As with historical breakthroughs in medical science, such a sweeping change in scope poses enormous challenges for health care educators. Trainees must graduate with knowledge and skills to practice in a new model of health care, yet faculty often lack the expertise to guide them. Over the last decade, the IOM,3 professional organizations, and primary care academicians4-8 have promulgated recommendations and strategies for enhancing physician education in community and population health. Yet recent survey data continue to show significant shortcomings in both curricula and outcomes in medical schools and primary care residency programs across the United States.9-11

Recognizing the above concerns, the University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Family Medicine (DFM), one of the largest family medicine departments in the United States with training sites in urban and rural communities throughout Wisconsin, sought to deepen its work in the areas of community and population health. The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) awarded the DFM a 5-year grant (September 2011-September 2016) to support the transformation from a DFM to a Department of Family Medicine and Community Health (DFMCH). Further driving the change was the department’s inclusion within the UW School of Medicine and Public Health, the first integrated school of medicine and public health in the nation. This transformative work has been broad and involves all areas of the DFMCH’s mission including clinical work, research, and education.

This report focuses on changes to residency education in community and population health at the Madison Family Medicine Residency Program, a 3-year program with 42 residents who train at four continuity clinic sites in Dane County, Wisconsin. In 2011, the community health curriculum in the Madison residency program consisted of a month-long block rotation in the first year and an expectation that a community medicine project be completed prior to graduation. The block rotation consisted of educational visits to community agencies and was supplemented with curricular modules on broad topics such as health policy and epidemiology. Residents often developed projects that were limited in scope and sustainability due to lack of time (8 allotted half days in each of the second and third years of training) and faculty involvement. Engagement with community members and application of data to inform these projects were limited in most cases.

The HRSA grant team assigned five of its coinvestigators (JL, RL, KR, BA, JE) to an education team focused on improving residency education around community and population health. We assessed the existing curriculum and retained the exposure to community resources and partners as well as foundational didactic sessions introducing basic principles of community health, health economics, health services, and health policy. We sought to supplement and contextualize these curricular concepts with real-time data related to patient panels and local populations. Faculty-championed community partnerships were developed to assure more formal and sustainable community-centered and data-informed engagement. We determined that successful implementation of these changes would require faculty development, as most of our faculty had not been exposed to a robust curriculum in these areas in their own family medicine training.

Faculty Development

Following a needs assessment via email survey (see Appendix), opportunities for faculty development on topics such as patient engagement, population health data literacy, addressing social determinants of health in clinical practice, and physician involvement in advocacy were identified and prioritized. Educational content was integrated into existing monthly faculty meetings and annual faculty development days for a total of 4 to 8 hours annually.

Residency Curricular Change

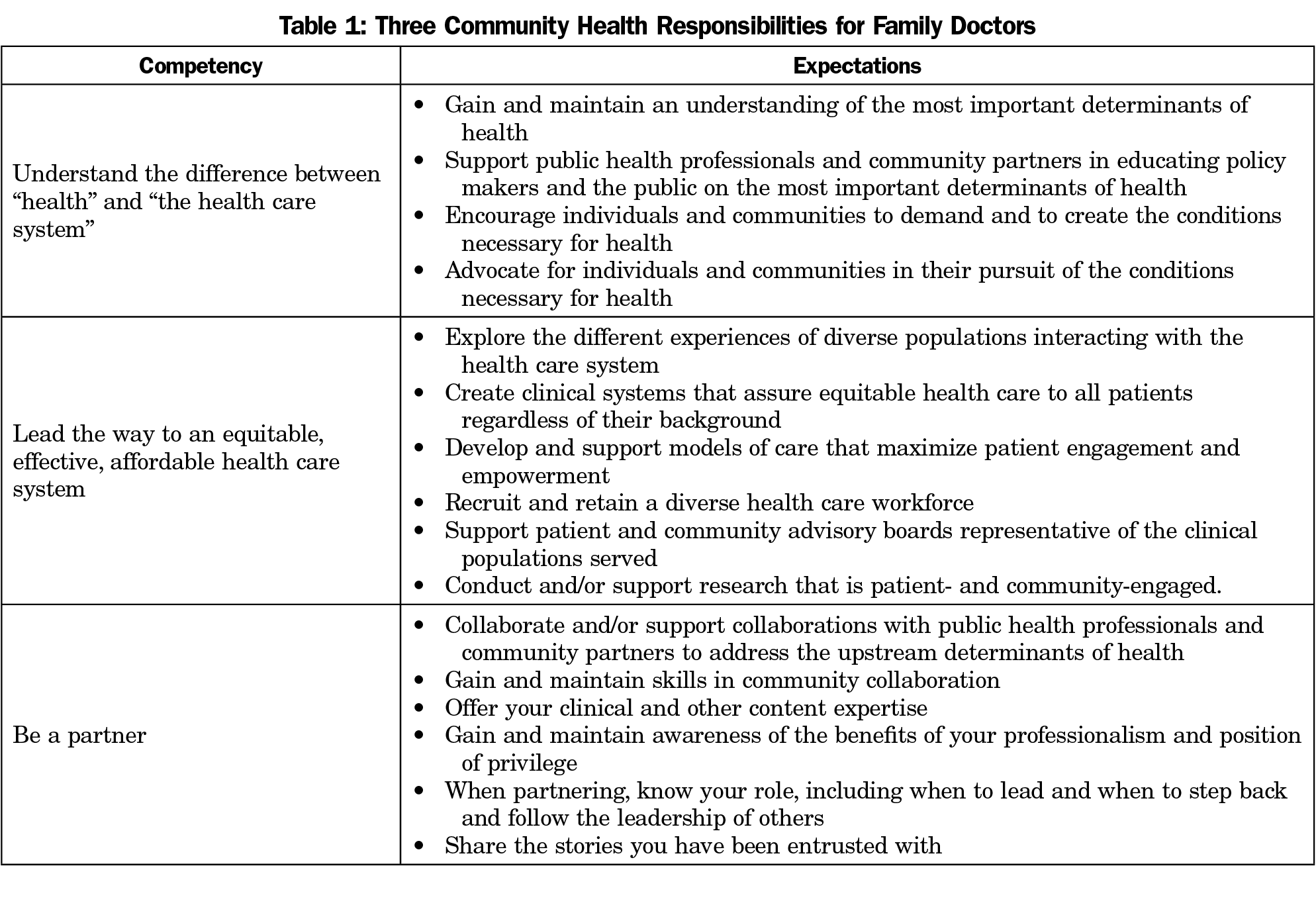

To provide a framework for ongoing curricular content development and revision for residency education and faculty development, a document was created addressing the fundamental question, “What should be the role of family physicians in improving community and population health?” Finding a dearth of answers to this question in published literature and through national family medicine organizations, we answered the question ourselves through iterative conversations with internal and external stakeholders. Our framework, “Three Community Health Responsibilities for Family Doctors,” outlines what we see as the essential community health competencies for family physicians: (1) understanding the difference between health and the health care system, (2) leading the way to an equitable, affordable health care system, and (3) being a community partner (Table 1). We chose to label this framework “responsibilities” for family doctors rather than just “competencies” in order to convey what we believe is a moral imperative to engage in this work.

The three main curricular innovations introduced included topic-based, clinic-oriented population health modules; clinic-based demographic and health community health practice profiles (CHPP) extracted from the electronic health record (EHR); and CHPP-informed, faculty-supported community engaged partnerships.

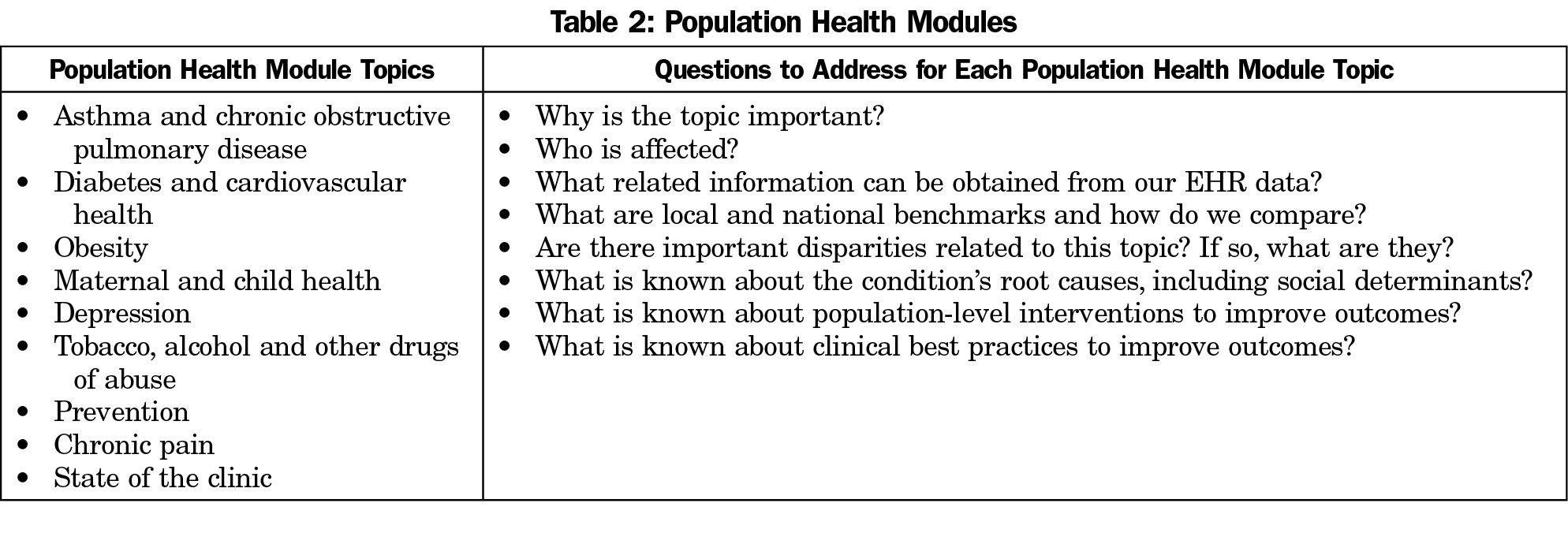

The population health modules, delivered over the course of 2 years, focus on nine core topics addressing eight questions on each topic (Table 2). The topics chosen include a variety of prevalent chronic diseases, maternal-child health, and prevention. All topics are amenable to analysis of internal data (from our EHR) and external data (from county, state, and national data sets) to support the goal of looking at health conditions from a community health perspective. The modules have helped residents reframe their approach to disease management and recognize the complex social determinants of health, including health inequities, which lie beyond clinical guidelines.

The CHPP combines EHR health and demographic data with publically available economic hardship data mapped for neighborhoods served by each clinic site. These data are incorporated in the population health modules to enhance learner engagement. For example, in examining racial disparity data for asthma at one clinic site, geo-mapping revealed a cluster of African-American patients with asthma who live within a mile of a meat processing plant. This finding led to discussion about potential environmental exposures that may impact asthma-related health outcomes.

The community-engaged partnerships are more rigorous and structured than the prior community medicine projects. A community needs assessment, evaluation of interventions, and equitable partnering with community members are now expected. Residents meet early in the process with faculty leaders to learn about current clinic-community partnerships and look at data in their CHPP to identify health issues that are relevant to their community.

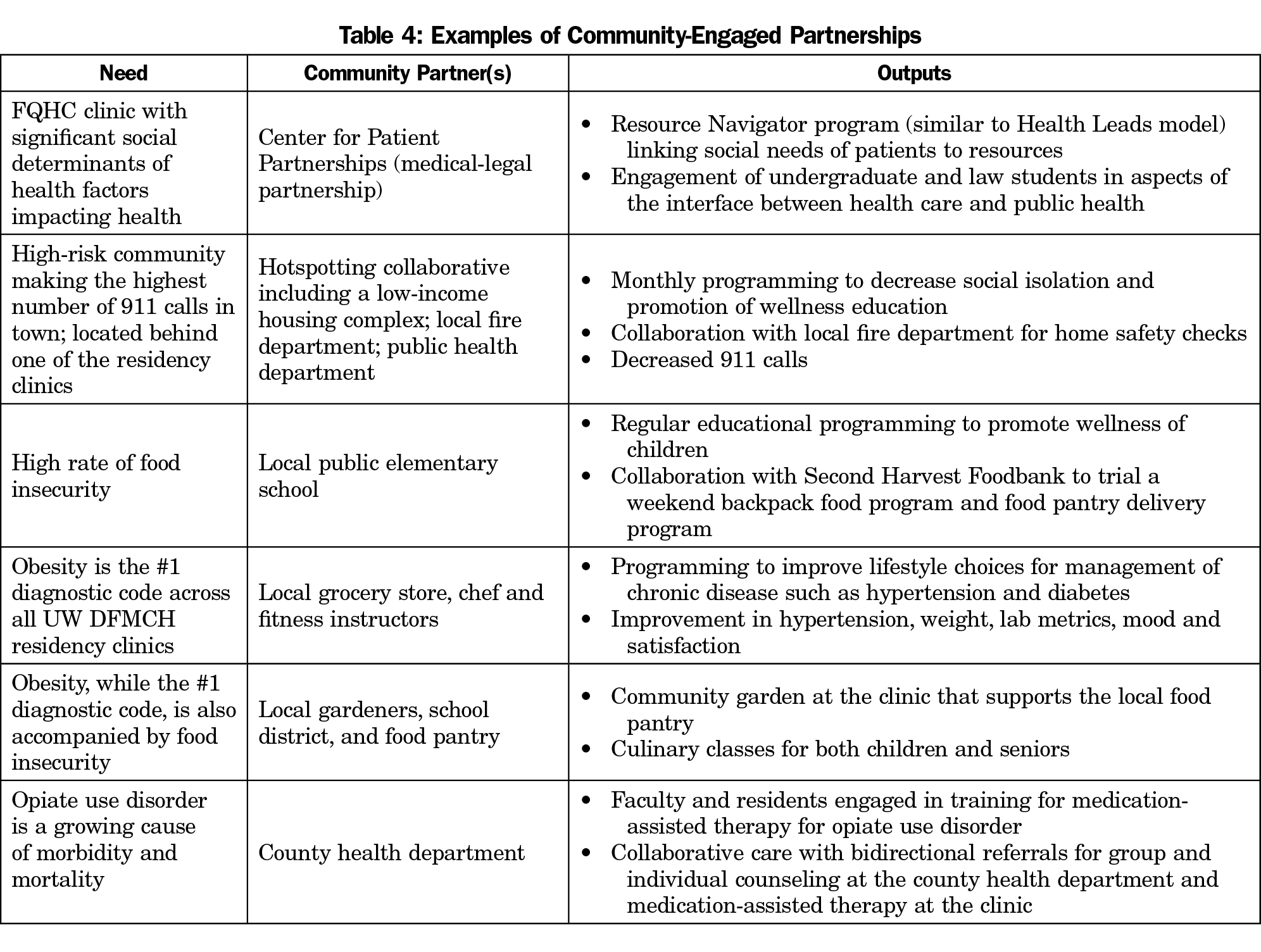

Our ultimate vision for this work is that each clinic will engage in one to two sustained partnerships involving faculty, residents, and staff. Residents will have opportunities to learn about initiating, sustaining, and growing partnerships throughout their training. As an example, faculty and residents at one clinic collaborated to engage obese patients in a novel 20-week group visit intervention focusing on lifestyle changes with an emphasis on healthy eating and practical approaches to fitness. It was founded on the principles of peer support, and also highlighted the importance of ongoing support from community partners, including financial incentives from local health maintenance organizations. Through this work, the clinic has formed enduring community connections with local grocery stores, restaurants, insurance companies, and fitness facilities. This annual intervention has led to improvements in individual health outcomes, including weight loss, improved mood, and decreased pain.12 Additional examples of community-engaged partnerships are briefly described in Table 4.

The goals of the community health curriculum for our residency have not substantially changed with the implementation of the new curricular elements. What has changed is improved access to data to support our work, and greater expectations of utilizing this data in tandem with personal interactions with leaders of community organizations.

In addition to the community-engaged partnerships, experiential components of the curriculum include workshops on health equity designed to help recognition of race as a social construct and racism as a social determinant of health. Participants discuss identity, intersectionality (how various social identities such as race, gender, class, or sexuality overlap and contribute to discrimination), and privilege. They also examine how these impact our perspective, communication, and action as health care providers and team members, how they contribute to ongoing health inequities, and how to identify and interrupt implicit bias on a personal and institutional level.

An annual survey of program faculty and residents developed by the primary investigator and coinvestigators of the HRSA grant assessed the impact of the curricular innovations outlined above. An electronic baseline survey was administered in 2012, and a follow-up survey was administered in each of the subsequent years of the grant period through 2016. The total number of faculty in the DFMCH during these years was between 125 and 142, and there were 42 total residents each year (14 per class). Kruskal-Wallis and chi-square testing was used to compare survey responses over time. The statistical analysis was performed using R version 3.2.4 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

According to the UW-Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board, this program evaluation work does not constitute research according to the definition of the Common Rule (45 CFR 46).

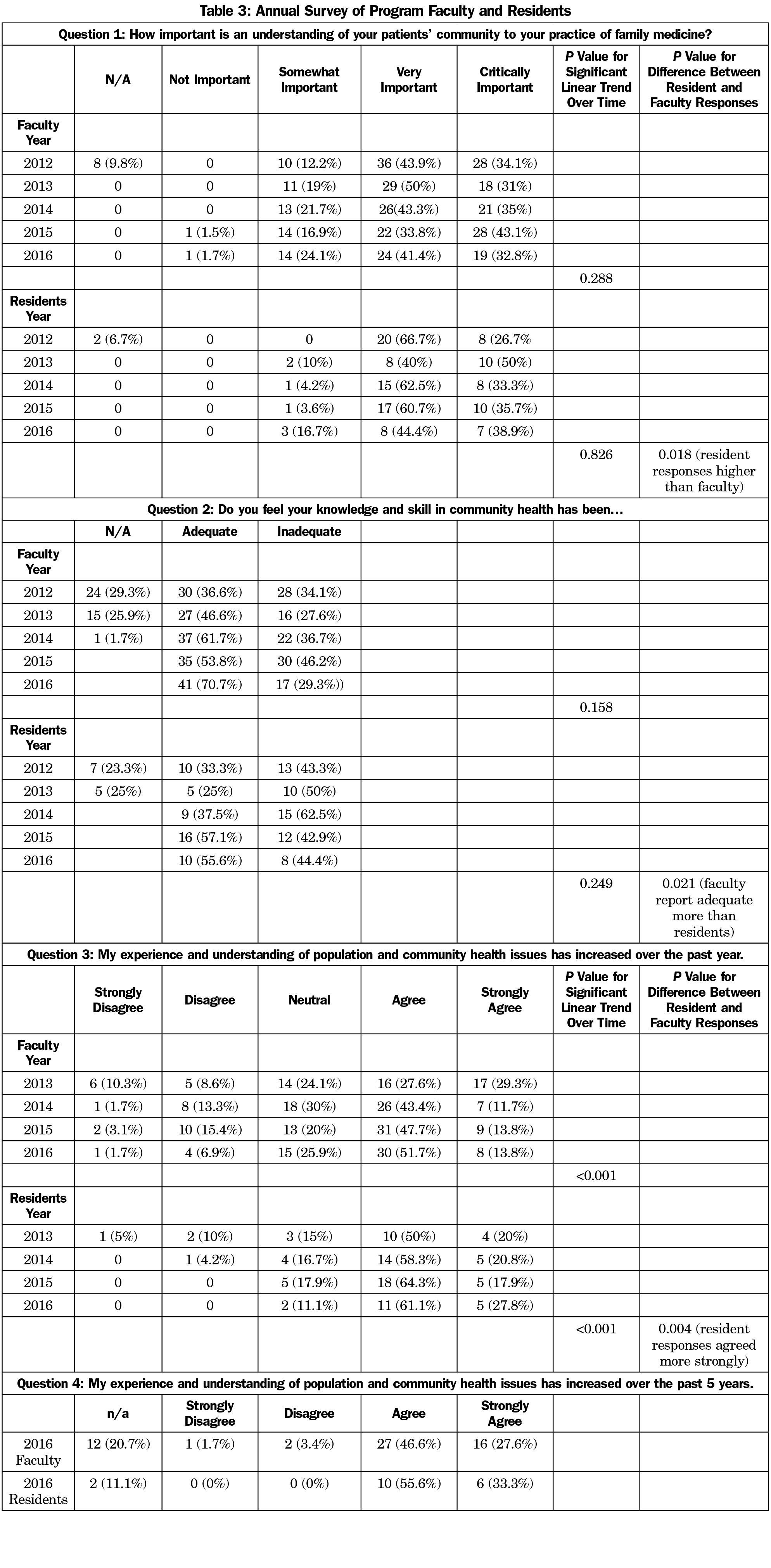

Faculty response rates for the annual survey were 60.3% in 2012, 40.8% in 2013, 45.5% in 2014, 53% in 2015, and 43.9% in 2016. Resident response rates were 71.4% in 2012, 47.6% in 2013, 57.1% in 2014, 66.7% in 2015, 42.9% in 2016.

Improved Knowledge and Skills

Faculty and resident survey respondents indicated that understanding their patients’ communities was either very important (faculty 43.9%, residents 66.7%) or critically important (faculty 34.1%, residents 26.7%) to their practice of family medicine at baseline in 2012, and this did not significantly change over time for either group (Table 3, P=0.288, P=0.826). Residents’ response scores for this question were consistently and significantly higher than faculty’s (Table 3, P=0.018). In 2016, the final year of the grant period, 70.7% of faculty and 55.6% of residents indicated they had adequate knowledge and skills in community health compared to 36.6% of faculty and 33.3% of residents at baseline in 2012. These are nonsignificant increases with P=0.158 for faculty responses and P=0.249 for resident responses over time. Residents reported significantly less adequate knowledge and skills than faculty (Table 3, P=0.021). Both resident and faculty survey respondents reported a significant increase in their understanding of population and community health over the past year for each of the 4 years this was assessed (Table 3, P<0.001, P<0.001). Residents reported significantly higher agreement with this statement than faculty (P=0.004). When asked in 2016 to reflect on the prior 5 years, 74.1% of faculty and 88.9% of residents agreed or strongly agreed that their experience and understanding of population and community health issues had increased.

One resident commented in the survey that

... in conjunction with other residency education opportunities, I feel that I am getting a wonderful useful exposure to the foundations of community health and will be able to apply the things I’ve learned to my future practice after graduation.

The main faculty concern about this work revolved around the lack of protected time for most faculty to engage in community work:

I understand it to be taking care of the community as a whole. To get to this point however we need someone that has dedicated time to take care of the community as a whole. As practitioners, I feel that we have a part in this, but it is often on the individual basis. I admire people that go above and beyond this and use their free time and family time to help the community. My family would understand, but they are ultimately more important to me at this time.

Faculty development and residency curricular change in the areas of population health and community health were critical components of the DFM’s transformation to a DFMCH. Survey data assessing the impact of these changes show a significant increase in faculty and residents’ experience and understanding of population and community health over the 5-year grant period.

Though not formally measured, we have found that residency curricular change around community and population health has led to a remarkable cultural shift in our family medicine residency. Community health is now woven into the fabric of our educational activities. For example, without prompting by the education team, our residency program altered their evaluation form such that all residency education seminars are now evaluated for community health content through questions about whether the content was patient-, family-, and community-centered and whether it addressed issues of health care inequities, cultural context, and/or social justice.

We recognize several limitations in our work. First, we are a single residency program that has benefitted from the financial support of a federal grant, allowing our education team to have funded time to design and implement curricular change. However, we view our team’s most useful output as not heavily grant dependent, and thus replicable in other settings. Our community partnerships used little of the formal grant funding, helping to ensure their sustainability. Creation of our population health teaching modules also relied heavily on open-access internet material such as Center for Disease Control and County Health Ranking data, graphs and maps. Clinic-specific data is produced for use by our clinic’s operational leadership; we repurpose it in an educational context. Second, the survey-based evaluation of our work must be viewed as preliminary and inconclusive given our low response rate and focus on assessing attitude and knowledge but not behaviors. In the future we plan to include questions regarding job duties and skills in community and population health in our graduate survey to see if our graduates are implementing these techniques in their practices. Third, we have not assessed any patient- or population-based outcomes thus far. These are more difficult to achieve, but they do remain the ultimate goal of our work.

The importance of faculty development in these areas cannot be overstated. As we worked on new curricular elements in community and population health, we found a need to educate ourselves and our faculty colleagues on these topics. Many faculty members had not had robust training in community health principles during their own family medicine training, and most were eager to engage in learning activities on topics of community and population health. In many cases, the sessions highlighted and recognized values and work that was already being done outside of formal job duties. These educational efforts have empowered our faculty to engage in and sustain community-driven partnerships as well as provide mentorship to residents and model community health competencies.

In summary, we found that curricular transformation toward community and population health led not only to improved learner outcomes in knowledge and experience in these areas, but it also lent support to important cultural changes across the department as a whole. We are now proud to be members of a Department of Family Medicine and Community Health.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Wen-Jan Tuan for data acquisition; Geng Li for assistance with statistical analysis, Mindy Smith, MD and Laura Cruz for editorial support, and Valerie Gilchrist, MD and John Frey, MD for obtaining funding for our work.

Previous presentations: Lankton R, Rindfleisch K, Gilchrist V, Edgoose J, Lochner J, Arndt B. What’s in a name? Transforming to a Department of Family Medicine and Community Health. Presented to physician, resident and student attendees of the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference; April 30-May 4, 2016; Minneapolis, MN.

Lochner J, Rindfleisch K, Lankton R. Taking care of the forest and the trees: integrating a population health approach into teaching family medicine clinics. Presented to physician, resident and student attendees of the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine/American Academy of Family Physicians Conference on Practice Improvement; December 4-7, 2014; Tampa, FL.

Funding/Support: This project was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number D54HP233299, “Transforming to a Department of Family Medicine and Community Health” for a total award of $752,716.00 (0% funded with nongovernmental sources). This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsement be inferred by HRSA, HHS of the US government.

References

- University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County Health Rankings 2012. http://www.countyhealthrankings.org. Accessed April 2, 2018.

- Alley DE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Sanghavi DM. Accountable Health Communities--Addressing Social Needs through Medicare and Medicaid. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):8-11. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1512532.

- Hernandez LM, Munthali AW, Institute of Medicine (US). Training physicians for public health careers. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=11915. Accessed April 2, 2018.

- Maeshiro R, Johnson I, Koo D, et al. Medical education for a healthier population: reflections on the Flexner Report from a public health perspective. Acad Med. 2010;85(2):211-219. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c885d8.

- Kaprielian VS, Silberberg M, McDonald MA, et al. Teaching population health: a competency map approach to education. Acad Med. 2013;88(5):626-637. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828acf27.

- Shtasel D, Hobbs-Knutson K, Tolpin H, Weinstein D, Gottlieb GL. Developing a Pipeline for the Community-Based Primary Care Workforce and Its Leadership: The Kraft Center for Community Health Leadership’s Fellowship and Practitioner Programs. Acad Med. 2015;90(9):1272-1277. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000806.

- Wolff M, Hamberger LK, Ambuel B, et al. The development and evaluation of community health competencies for family medicine. WMJ. 2007;106(7):397-401.

- Clancy GP, Duffy FD. Going “all in” to transform the Tulsa community’s health and health care workforce. Acad Med. 2013;88(12):1844-1848. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000039.

- Jones MD Jr, McGuinness GA, First LR, Leslie LK. Residency Review and Redesign in Pediatrics Committee. Linking process to outcome: are we training pediatricians to meet evolving health care needs? Pediatrics. 2009;123(suppl 1):S1-S7. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-1578C.

- Vickery KD, Rindfleisch K, Benson J, Furlong J, Martinez-Bianchi V, Richardson CR. Preparing the Next Generation of Family Physicians to Improve Population Health: A CERA Study. Fam Med. 2015;47(10):782-788.

- Catalanotti JS, Popiel DK, Duwell MM, Price JH, Miles JC. Public health training in internal medicine residency programs: a national survey. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(5)(suppl 3):S360-S367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.024.

- Larson M, Minichiello V, Hahn T, Yates J, Prince R, Arndt B. Community supported interdisciplinary clinic based group visits: a pilot-level quality improvement project on obesity, quality of life, mental health and healthy lifestyle behaviors. Presented at the 2016 North American Primary Care Research Group Annual Meeting; November 12-16; Colorado Springs, CO.

There are no comments for this article.