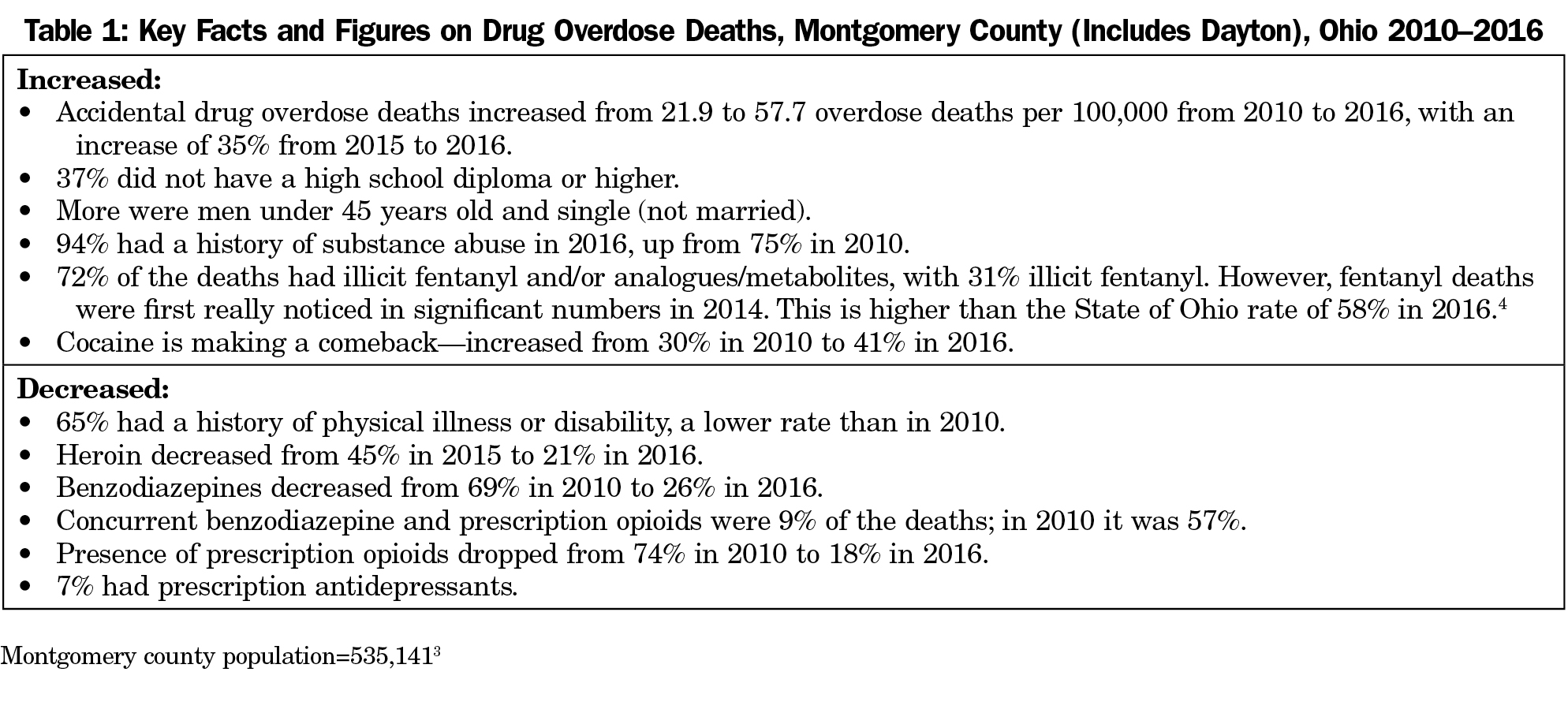

Dayton and surrounding counties top Ohio’s list of deaths from drug overdose,1 and Ohio is one of 10 states that continued to see increases in overdose deaths from 2016 to 2017 (Table 1).2-4 Opioid and other drug abuse is very much a family physician type of problem, ie, multifactorial, involving medical issues, health system issues, and the social determinants of health. We are all aware of the seriousness of this crisis, but it takes on a completely different dimension when viewed from the perspective of a worker at its epicenter.

After years of little narcotic prescribing for chronic pain, I moved to Dayton and found myself prescribing opioids to patients who were started on them by departing or retiring physicians. The previous doctors meant well and were overall good doctors. Many believe physician prescribing is a primary cause of this epidemic. It certainly is an important factor, but drug overdoses were too common even before increased opioid drug prescribing by physicians. Prescription narcotics have been aggressively marketed to patients as well as health providers leading to a growing acceptance that chronic pain could be safely treated with narcotics.5 My personal belief is that the primary causes of overdose deaths are the addictive nature and ready availability of these substances and many of the classic social determinants of health.6

Socioeconomic problems and a pessimism for improvement in life circumstances were certainly key factors in drug abuse in Dayton, a high-output manufacturing city, where the economy died fairly quickly starting in the early 1970s,7 leading to high unemployment. This was a fertile environment for drug abuse to increase. In addition, Dayton is at the crossroads of two major interstate truck routes, Route 70 (east-west) and Route 75 (north-south), allowing ready access to the illegal drug trade. Many chronic opioid users are construction workers or other physical laborers.8 It is scary to have patients taking opioids while working on roofs, yet when I look at their battered hands and joints, it is easy to understand pain relief can be the difference between their ability to work, and a life without sufficient income.

I also believe drug abuse is frequently intergenerational, and contagious, creating massive social side effects. For example, we do not have enough foster families for the many children who need care because of parental drug abuse. One of the families in my practice temporarily had 11 concurrent foster children. The children of another family epitomized the problem–the oldest child was clearly in charge and had beautiful teeth, the middle child had a couple of cavities, and the youngest had no cavity-free teeth. The parents’ story of advancing drug use and lack of parenting was told through their children’s teeth, behavior, and foster placement.

Over and beyond the classic socioeconomic issues—pessimism and the lack of economic opportunity—many entities share responsibility for this problem. Drug companies, the profit motive,9 the government, the rules by which workers live, technology aiding the ability to make, buy, and sell illegal drugs, better transportation routes, the lack of adequate education, our prison systems and their apparent permeability to drugs, the lack of adequate payment for known alternatives to easy-to-take and cheap narcotics, doctors, and, yes, the patients themselves. The cause is multifactorial, and improvement will take many concurrent solutions.10

The physician challenge is how to assist patients on chronic opioids for pain and those with drug addiction. These two overlapping groups might require different tactics. Many of the patients on prescription opioids have been on them for many years, sometimes decades, without significant evidence of problematic addiction. The treatment will differ for the patients with drug addiction, whose options are either to attempt to get prescriptions from health care workers or get drugs from the streets, leading to overdoses, arrests, and additional social disruption. My personal goal is to identify where patients are on this spectrum in order to best assist them and their families.

In spite of the obstacles, we as family doctors can and should do what we do best: keep working with our patients. We need to partner to tackle the difficulties, providing support and appropriate treatment as best we can. We can and will, slowly, see improvements. Chronic illness requires many interventions, over time, with understanding that relapse is part of the learning about how to sustain change. One of my exemplar patients, after many failed attempts over 5 years, did a classic environmental change to get off opioids—she purposefully did not take her narcotics with her on an overseas trip, went through withdrawal starting on the airplane, was clean for her 3-week trip, and then permanently. And in one day last week I had two patients thank me profusely for getting them off of narcotics, and two others that had become tobacco free. Wow! That was a good day. And, it gives me ongoing hope. I maintain optimism, and hope to see some success every time I see patients.

Upcoming in Ohio and other states is another understudied and overlapping issue—marijuana. Medical marijuana is now becoming available in Ohio, yet we have little data from other states on what this will mean, and little research available, representing another experiment in mixed medical/social change.

For our academic physicians, residents, and students, the opiate/drug abuse crisis epitomizes a public health and medical interface that creates a call to action. We can lobby to improve our many laws, regulations, and policies that hurt the nation’s ability to prevent initiation and stop ongoing drug abuse. Within our own sphere, incorporating appropriate training into our medical schools and residencies is an obvious must-do. And, to enhance our ability to know what to do, we should bring the incredible force of our research in real-life settings and conditions to assist all potential layers of action.

Between our ability to influence the training of our future health care workforce, our research capability, and our drive to make a difference for our patients, we family physicians can and should make a real impact on the otherwise disheartening and horrible effects of opioid and other addictive drug misuse and abuse.

There are no comments for this article.