Background and Objectives: The military population is frequently overlooked in civilian primary care due to an assumption that they are treated at the Veterans Health Administration (VA). However, less than 50% of eligible veterans receive VA treatment. Primary care providers (PCPs) may need support in addressing veterans’ needs. This regional pilot study explored the current state of practice among primary care providers as it pertains to assessing patients’ veteran status and their knowledge of and comfort with treating common conditions in this population.

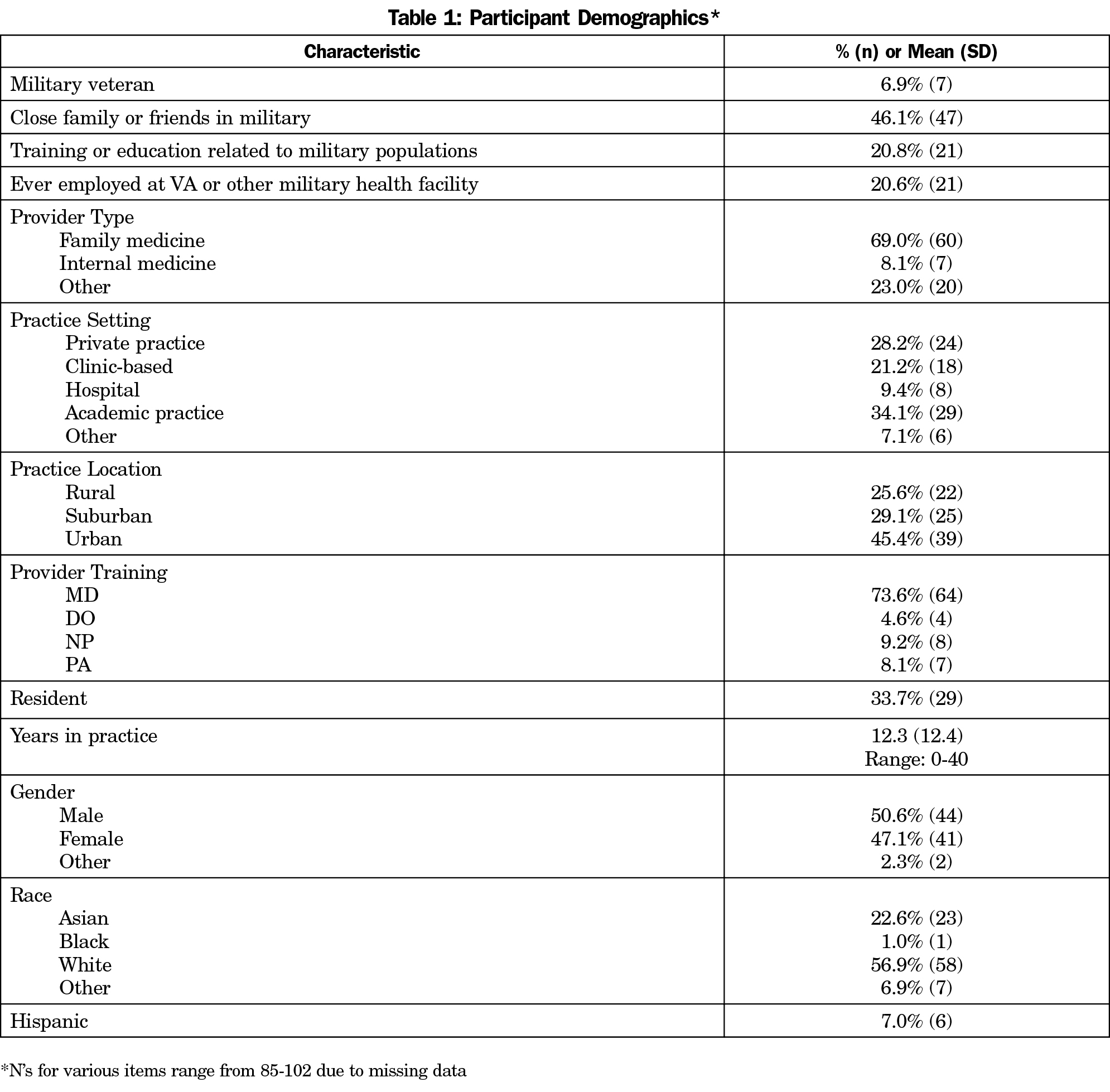

Methods: An electronic survey was administered to PCPs (N=102) in Western New York. Survey questions asked about assessing military status, understanding of military-related health problems, and thoughts on the priority of addressing these issues in practice. Data were analyzed using descriptive summary statistics.

Results: The majority (56%; n=54) of respondents indicated they never or rarely ask their patients about military service, and only 19% (n=18) said they often or always ask. Seventy-one percent (n=68) of providers agreed or strongly agreed it was important to know if their patient was a veteran. Participants indicated limited knowledge about military stressors, resources available for military populations, and common medical conditions impacting veterans.

Conclusions: Our pilot results demonstrate that in a regional sample of primary care providers, providers rarely ask patients about their military history; however, they feel it is important information for patient care. While further study is needed, it may be necessary to provide education, specifically pertaining to military culture and health-related sequelae, to address barriers that may be limiting PCPs’ provision of care for this population.

There are approximately 20 million veterans in the United States.1 Veterans are at high risk for many negative health conditions related to deployment, combat, and the challenges of reintegration,2-7 including higher rates of substance use disorders,2-4 smoking,4,8 and suicide.4

The military population is frequently overlooked in civilian primary care due to an assumption that they are receiving care through the Veterans Health Administration (VA).6,9,10 However, in reality, health care for this population is much more complex and may include any combination of care at the VA, at military treatment facilities (operated by the Department of Defense), and in the civilian health care system. Less than 50% of eligible veterans receive treatment through VA facilities6,9,10 and 25% to 45% of veterans who use the VA simultaneously obtain care from other sources,11,12 particularly in rural areas.11,13

Civilian health care providers have been called upon to screen their patients for veteran status and become familiar with the health impacts of military service.6,14,15 These recommendations appear to have had little impact on practice, with military service called “the unasked question” in health care.15 One study assessed community primary care providers’ perceptions and comfort with veterans’ health care problems, and found low comfort in addressing common issues.16

Given limited research specific to how civilian primary care providers address the needs of veteran patients, this regional pilot study explored current practices among primary care providers in Western New York (WNY) in regards to assessing patients’ veteran status and their knowledge of and comfort with identifying and treating common conditions in this population.

Participants were primary care providers (MDs, DOs, NPs and PAs) currently in civilian practice in WNY (N=102). Data were collected using an anonymous electronic survey. The survey was distributed via email through provider networks, including the local chapter of the New York State Academy of Family Physicians, university academic departments, the community health center network, the local practice-based research network, and other provider organizations. The study team contacted individuals responsible for administering these email lists and requested that they send an approved message containing a link to the survey to all of their providers. Due to the nature of this recruitment, it is not possible to determine a response rate to the survey, as it is unknown how many individuals were reached through these mass emails. Contacts were asked to send the email to their providers at least twice, and in most cases the second email was sent within 2 to 4 weeks of the initial request.

The study team also attended provider meetings at eight family medicine practices to introduce the survey and solicit participation. The survey was emailed to the providers within 1 day of the meeting, although at some practices participants were able to complete the surveys during the meeting. Participants could enter into a drawing to win one of two iPads. The survey was prefaced by an IRB information sheet, and survey submission was deemed as consent. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at the University at Buffalo.

Survey questions were modified, with permission, from a similar survey conducted with mental health providers.17 Questions addressed providers’ current practices pertaining to screening and documenting military status, knowledge and comfort in identifying and treating veterans’ health problems, and thoughts on the priority of addressing these issues. Finally, the survey solicited feedback on training and educational needs. Additional items assessed provider demographics, years in practice, practice type, geographic location, and whether or not the providers themselves were veterans or military family members or had worked at the VA or another military treatment facility.

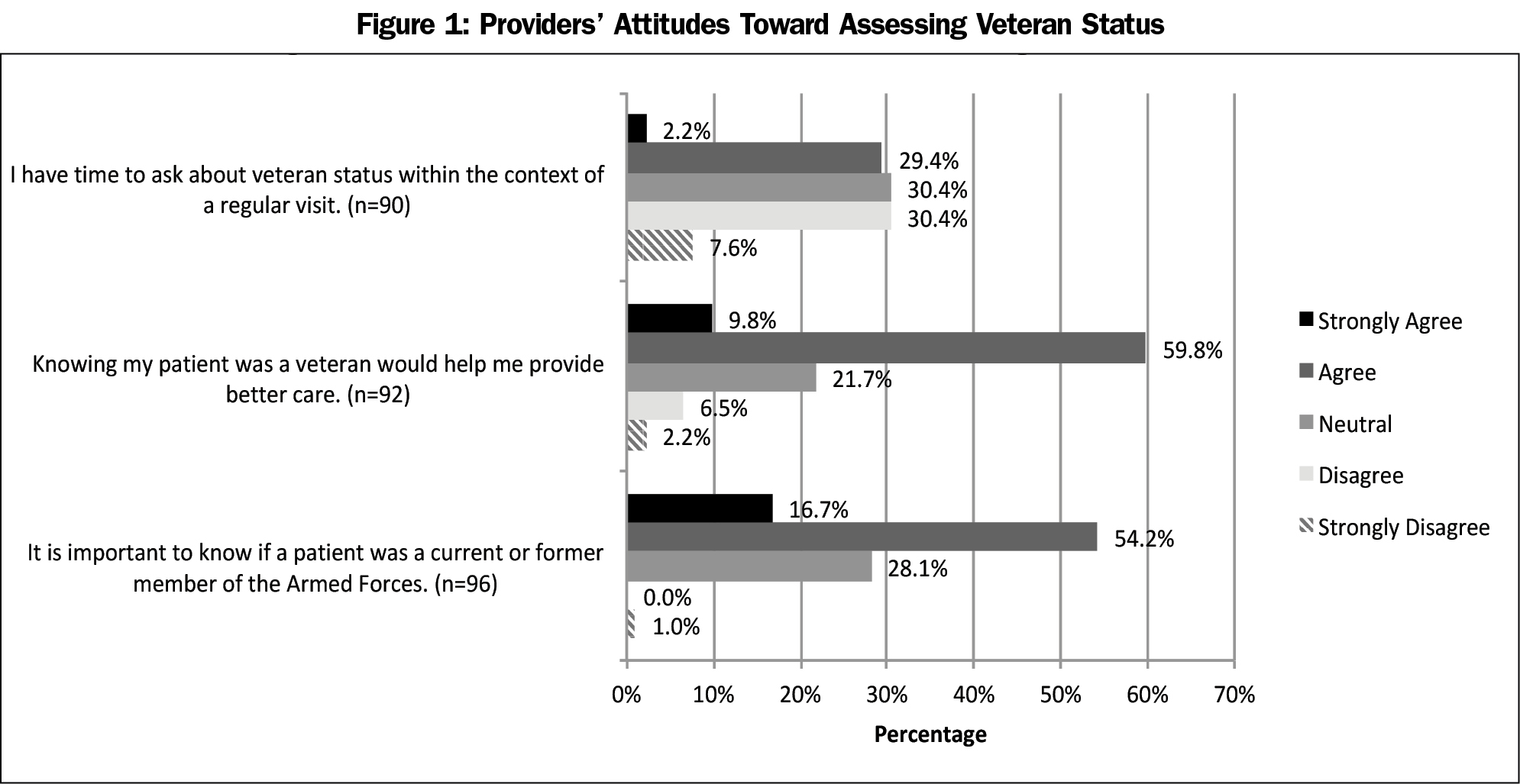

Participant demographics are presented in Table 1. The majority (56.3%; n=54) of respondents indicated that they “never/rarely” ask their patients if they have served in the military, 25% (n=24) “sometimes” ask, and 18.8% (n=18) said they “often” or “always” ask. Seventy-one percent (n=68) of providers “agreed/strongly agreed” that it was important to know if their patient was a veteran, and 70.9% (n=68) “agreed/strongly agreed” that knowing would help them provide better care. Only 38.0% (n=35) of participants “disagreed/strongly disagreed” that they had time to ask about veteran status (Figure 1).

Participants were asked to rank the top three problems they felt a veteran might face. The top three identified concerns were: depression/anxiety (70.6%), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; 66.7%), and family stress/relationship problems (42.2%). The majority of participants “agreed/strongly agreed” that knowing a patient was a veteran would change how they would address all conditions listed (Table 2). For most conditions, the majority of providers indicated comfort in diagnosing and addressing the concern.

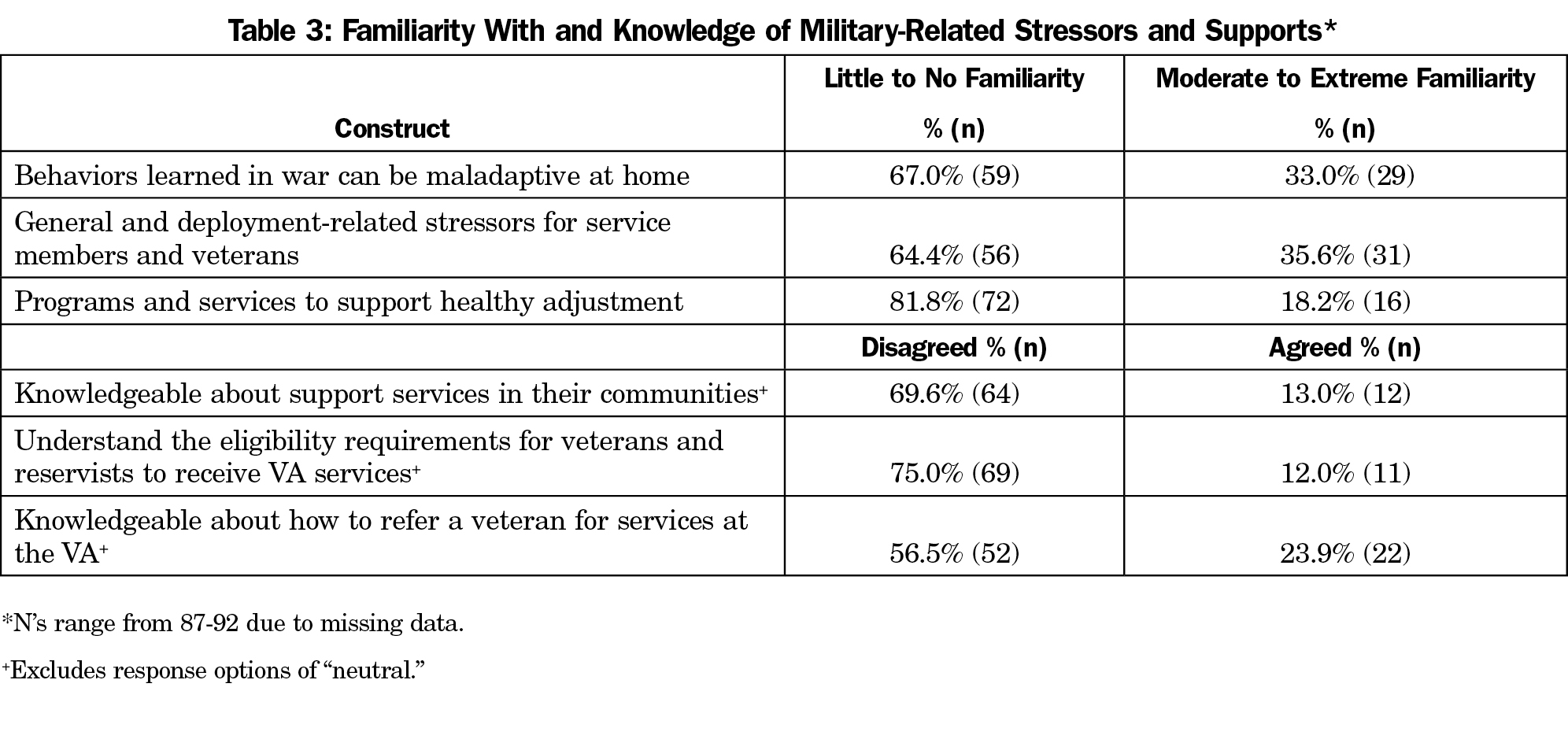

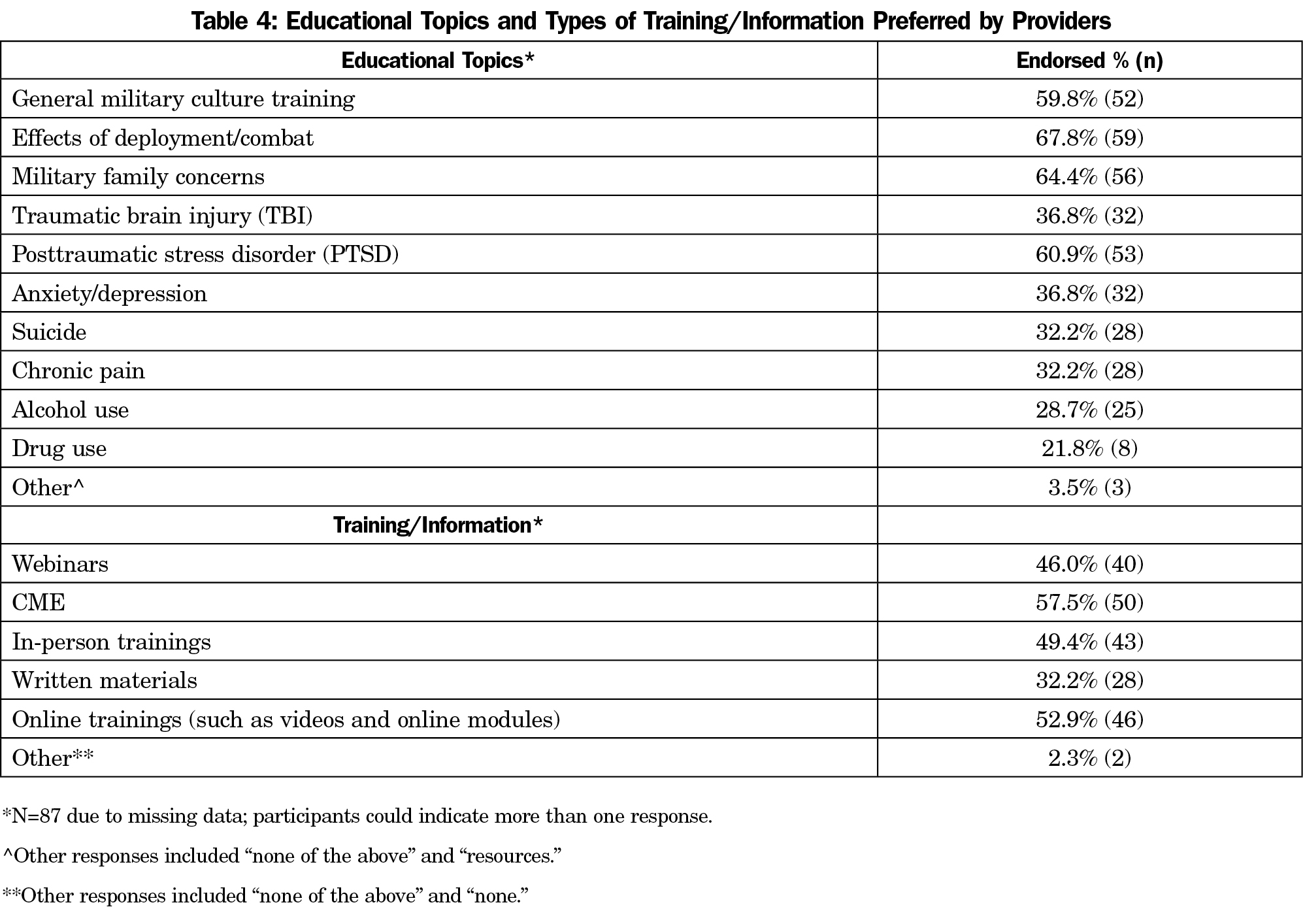

The majority of participants indicated limited familiarity with military stressors, limited knowledge of support services and VA systems, and limited time and resources for learning more, despite their interest (Table 3). Participants’ preferences for educational topics and format are presented in Table 4.

Results demonstrate that only 19% of primary care providers regularly ask patients about military service history; however, nearly three-fourths agree it is important to patient care to know veteran status. Furthermore, they feel this information would help them provide better care to their patients and may change how they diagnose and treat certain conditions.

Given that providers see this information as important and helpful to providing better care, one presumed barrier to not asking would be limited time; however, only 38% of providers felt they did not have time to ask their patients about military participation. Asking the question as part of routine demographic questions has been recommended as an easy way to determine whether further follow-up is needed.6

Providers may also have limited insight into the possible impacts of military service, reporting they were generally unfamiliar with military stressors. While providers identified PTSD, depression, and anxiety as common problems, very few identified substance use or traumatic brain injury as top concerns, despite their prevalence among this population.3,18-20 Furthermore, providers indicated lower levels of comfort addressing prevalent conditions among veterans.

Providing educational interventions to address barriers that may limit physicians’ identification and care of patients who are veterans is important. Providers more strongly endorsed their desire for training in military culture and effects of deployment than a need for education on specific medical conditions. Education that encompasses military cultural competency and health-related sequelae of military participation could help providers better engage veteran patients and recognize potentially under-addressed health problems. However, providers in our study identified lack of time for educational activities and limited knowledge of available resources, which may be barriers to caring for veteran patients.

This study is subject to limitations. First, the regional sample may not be representative of primary care providers generally. However, our sample included providers from a wide range of geographic areas, practice types, and educational backgrounds, enhancing generalizability. Second, provider responses about veteran care may be subject to an acceptability bias, thus, the survey was completely anonymous.

Future work is needed to identify interventions most effective in prompting providers to ask about veteran status. Importantly, our results demonstrate that once veterans are identified, primary care providers may need training to help better meet their needs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Chester H. Fox, MD for his guidance on study design and assistance with accessing primary care providers and offices.

Funding Statement: This project was funded by the American Academy of Family Physicians Foundation, Joint Grant Awards Program, Grant # G1601JG; PI: Vest. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award Number UL1TR001412. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Dr Kulak’s time was supported through Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) award #T32HP30035 to the University at Buffalo Primary Care Research Institute (PI: Kahn).

Presentations: Portions of this work were presented at the American Public Health Association Annual Conference in Atlanta, GA, November 4-8, 2017.

References

- US Census Bureau. US Census Bureau Quick Facts: 2015. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045216/00. Accessed May 25, 2017.

- Eisen SV, Schultz MR, Vogt D, et al. Mental and physical health status and alcohol and drug use following return from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(S1)(suppl 1):S66-S73. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300609.

- Seal KH, Cohen G, Waldrop A, Cohen BE, Maguen S, Ren L. Substance use disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in VA healthcare, 2001-2010: implications for screening, diagnosis and treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;116(1-3):93-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.027.

- Tanielian T. Assessing Combat Exposure and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Troops and Estimating the Costs to Society: Implications from the RAND Invisible Wounds of War Study. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2009.

- Clauw DJ, Engel CC Jr, Aronowitz R, et al. Unexplained symptoms after terrorism and war: an expert consensus statement. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45(10):1040-1048. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jom.0000091693.43121.2f.

- Hinojosa R, Hinojosa MS, Nelson K, Nelson D. Veteran family reintegration, primary care needs, and the benefit of the patient-centered medical home model. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(6):770-774. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2010.06.100094.

- Levy BS, Sidel VW. Health effects of combat: a life-course perspective. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30(1):123-136. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100147.

- Smith TC, LeardMann CA, Smith B, et al. Longitudinal assessment of mental disorders, smoking, and hazardous drinking among a population-based cohort of US service members. J Addict Med. 2014;8(4):271-281. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000050.

- Finley EP, Zeber JE, Pugh MJV, et al. Postdeployment health care for returning OEF/OIF military personnel and their social networks: a qualitative approach. Mil Med. 2010;175(12):953-957. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-10-00040.

- Straits-Tröster KA, Brancu M, Goodale B, et al. Developing community capacity to treat post-deployment mental health problems: a public health initiative. Psychol Trauma. 2011;3(3):283-291. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024645.

- Nayar P, Apenteng B, Yu F, Woodbridge P, Fetrick A. Rural veterans’ perspectives of dual care. J Community Health. 2013;38(1):70-77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-012-9583-7.

- Vaughan C, Schell TL, Jaycox LH, Marshall G, Tanielian T. Quantitative Needs Assessment of New York State Veterans and Their Spouses. In: Schell TL, Tanielian T, eds. A Needs Assessment of New York State Veterans: Final Report to the New York State Health Foundation. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2011:23-52.

- Gaglioti A, Cozad A, Wittrock S, et al. Non-VA primary care providers’ perspectives on comanagement for rural veterans. Mil Med. 2014;179(11):1236-1243. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00342.

- Spelman JF, Hunt SC, Seal KH, Burgo-Black AL. Post deployment care for returning combat veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(9):1200-1209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2061-1.

- Brown JL. A piece of my mind: the unasked question. JAMA. 2012;308(18):1869-1870. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.14254.

- Fredricks TR, Nakazawa M. Perceptions of physicians in civilian medical practice on veterans’ issues related to health care. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2015;115(6):360-368. https://doi.org/10.7556/jaoa.2015.076.

- Kilpatrick DG, Best CL, Smith DW, Kudler H, Cornelison-Grant V. Serving Those Who Have Served: Educational Needs of HealthCare Providers Working with Military Members, Veterans, and their Families. South Carolina: Medical University of South Carolina Department of Psychiatry, National Crime Victims Research & Treatment Center; 2011.

- Bray RM, Pemberton MR, Lane ME, Hourani LL, Mattiko MJ, Babeu LA. Substance use and mental health trends among U.S. military active duty personnel: key findings from the 2008 DoD Health Behavior Survey. Mil Med. 2010;175(6):390-399. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-09-00132.

- Snell FI, Halter MJ. A signature wound of war: mild traumatic brain injury. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2010;48(2):22-28. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20100108-02.

- Tanielian T, Jaycox LH. Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2008.

There are no comments for this article.