Background and Objectives: Worsening faculty shortages in medical schools and residency programs are threatening the US medical education infrastructure. Little is known about the factors that influence the decision of family medicine residents to choose or not choose academic careers. Our study objective was to answer the following question among family medicine residents: “What is your greatest concern or fear about pursuing a career in academic family medicine?”

Methods: Participants were family medicine residents who attended the Faculty for Tomorrow Workshop at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference in 2016 and 2017. Free responses to the aforementioned prompt were analyzed using a constant comparative method and grounded theory approach.

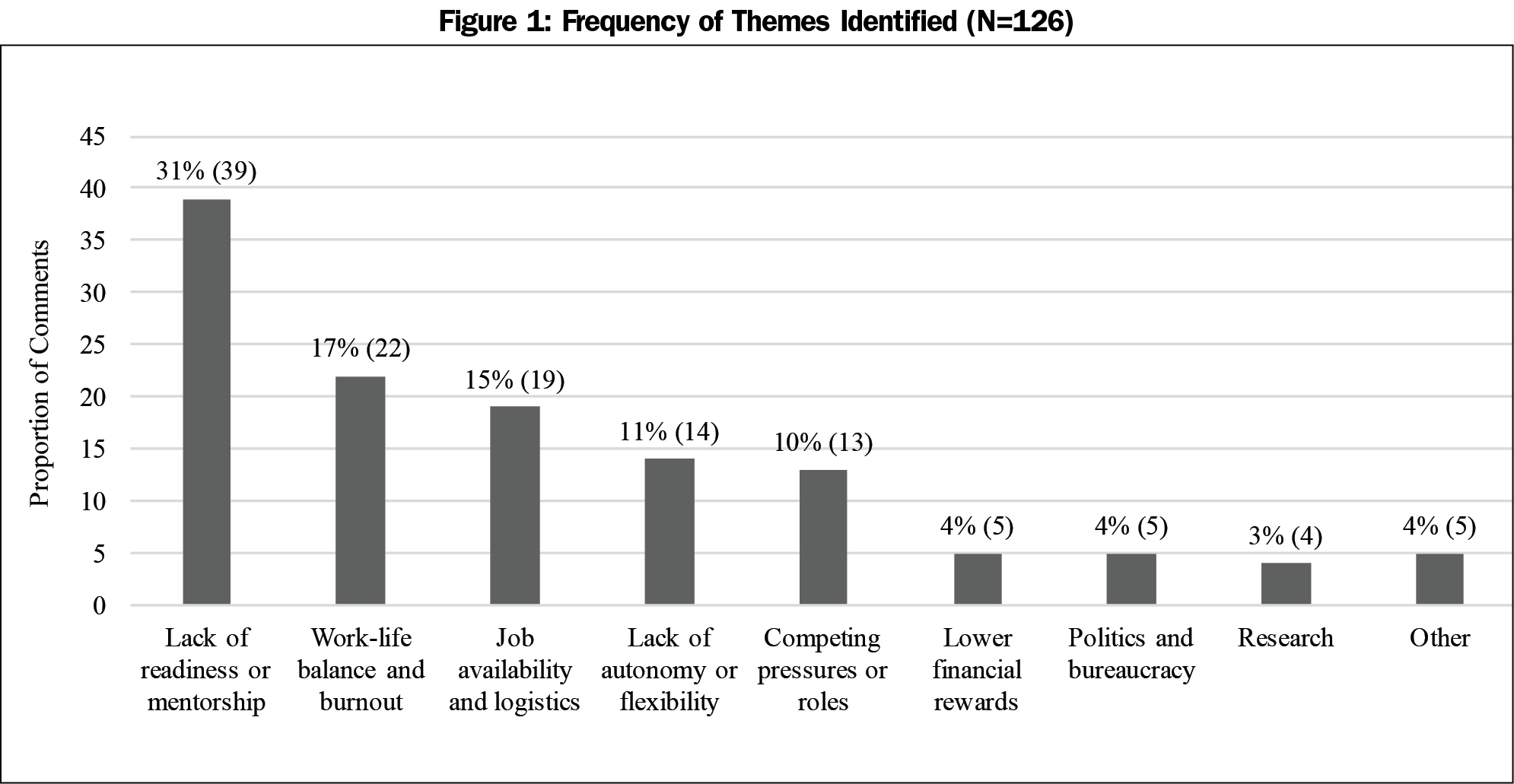

Results: A total of 156 participants registered for the workshops and 95 (61%) answered the free response question. Eight distinct themes emerged from the analysis. The most frequently recurring theme was “lack of readiness or mentorship,” which accounted for nearly one-third (31%) of the codes. Other themes included work-life balance and burnout (17%), job availability and logistics (15%), lack of autonomy or flexibility (11%), competing pressures/roles (10%), lower financial rewards (4%), politics and bureaucracy (4%), and research (3%).

Conclusions: To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify barriers and disincentives to pursuing a career in academic medicine from the perspective of family medicine residents. There may be at least eight major obstacles, for which we summarize and consider potential interventions. More research is needed to understand why residents choose, or don’t choose, academic careers.

Worsening faculty shortages in medical schools and residency programs across the United States are threatening the nation’s medical education infrastructure.1-3 According to the Association of Academic Health Centers (AAHC), 70% of chief executives of academic health centers declared faculty shortages to be a serious problem.1 In 2016, 87% of medical schools were “moderately or very concerned” about the supply of primary care preceptors.2 Department chairs and residency program directors nationwide have reported that they cannot fill open faculty positions.3 These worrisome trends shed light on a looming problem: without sufficient faculty members to teach the next generation of physicians, the nation’s health systems are in jeopardy.

Several reasons may account for the widespread faculty shortages, including low level of interest in academic careers among residents, high level of burnout and competing pressures in academic life, lack of role models and mentors, and sharp disparities in financial reward between academia and private practice or industry.4,5 Two recent systematic reviews concluded that the question of how, when, and why physicians choose academic careers remains “essentially unanswered,” and that more research is needed because the literature is scant and outdated.4,5 Many existing studies have been limited by small sample sizes and single institution sampling; few studies, if any, have explored the perspectives of family medicine residents specifically.4,5

Understanding which factors influence the decision of family medicine residents to choose or not choose a career in academic medicine is vital to addressing the critical shortage of faculty and its threat to the nation’s health systems. Our study’s objective was to answer the following question among family medicine residents: “What is your greatest concern or fear about pursuing a career in academic family medicine?”

Participants

Participants were family medicine residents who attended the Faculty for Tomorrow Workshop at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine’s (STFM) Annual Spring Conference in 2016 and 2017, held in Minneapolis, MN and San Diego, CA, respectively. The workshop was a free, full-day, 9-hour program designed to increase residents’ interest in, and prepare them for, careers in academic family medicine. Participants learned about the workshop through STFM marketing, website, digital newsletter, and social media.

Survey

Data for this research was collected as part of a larger study evaluating the Faculty for Tomorrow Workshop, described elsewhere in the literature.6 Participants were asked to complete an 18-item preworkshop questionnaire; questions included demographics, residency program characteristics, and future career plans. At the end of the survey, participants were asked: “What is your greatest concern or fear about pursuing a career in academic family medicine?” as a free response with a 500-character limit. The Faculty for Tomorrow Task Force chose to frame the question this way after a literature review4,5 and field testing with residents, with the intent to generate a ranked list of concerns that can be used by STFM for strategic planning. Questionnaires were voluntary and anonymous.

Qualitative Analysis

A codebook was developed using a constant comparative method—grounded theory approach.7 One reviewer (SL) identified and defined recurring themes from the free responses using a data-driven approach with triangulation from literature. Two coders (CN, SL) independently reviewed each response and labeled it according to the codebook. The content units for data analysis were words and phrases. Interrater agreement was analyzed using Cohen’s kappa coefficient.

Ethical Approval

This study was granted an exemption by the Institutional Review Board of Stanford University School of Medicine.

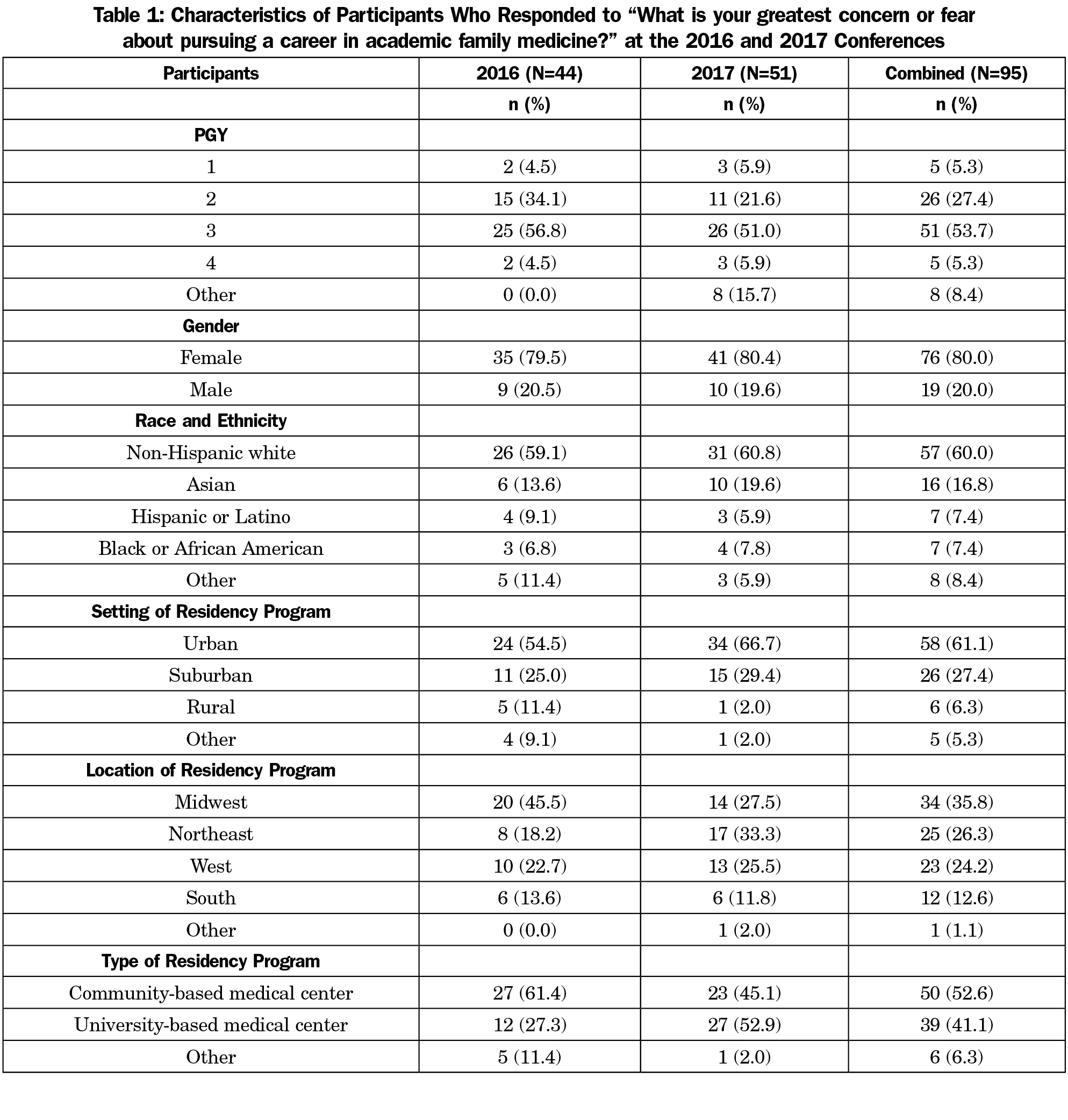

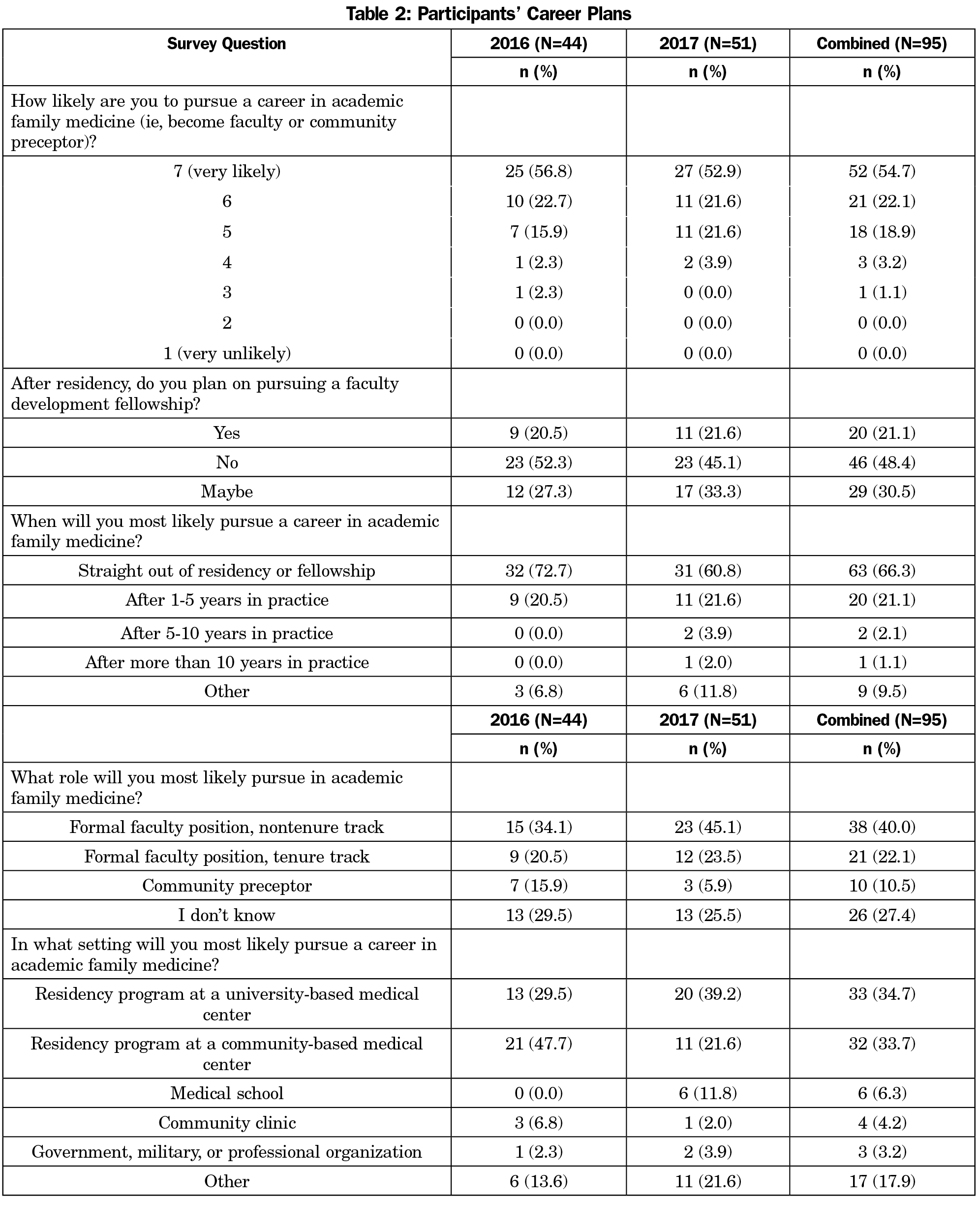

A total of 156 participants registered for the workshops in 2016 and 2017. Of those who registered, 126 (81%) completed the questionnaire, and 95 (61%) answered the free response question. Most participants were PGY-3 (54%), female (80%), white (60%), and came from urban (61%), community-based (53%) residency programs. Overall, our participants broadly represented family medicine residents nationally8 (Tables 1 and 2).

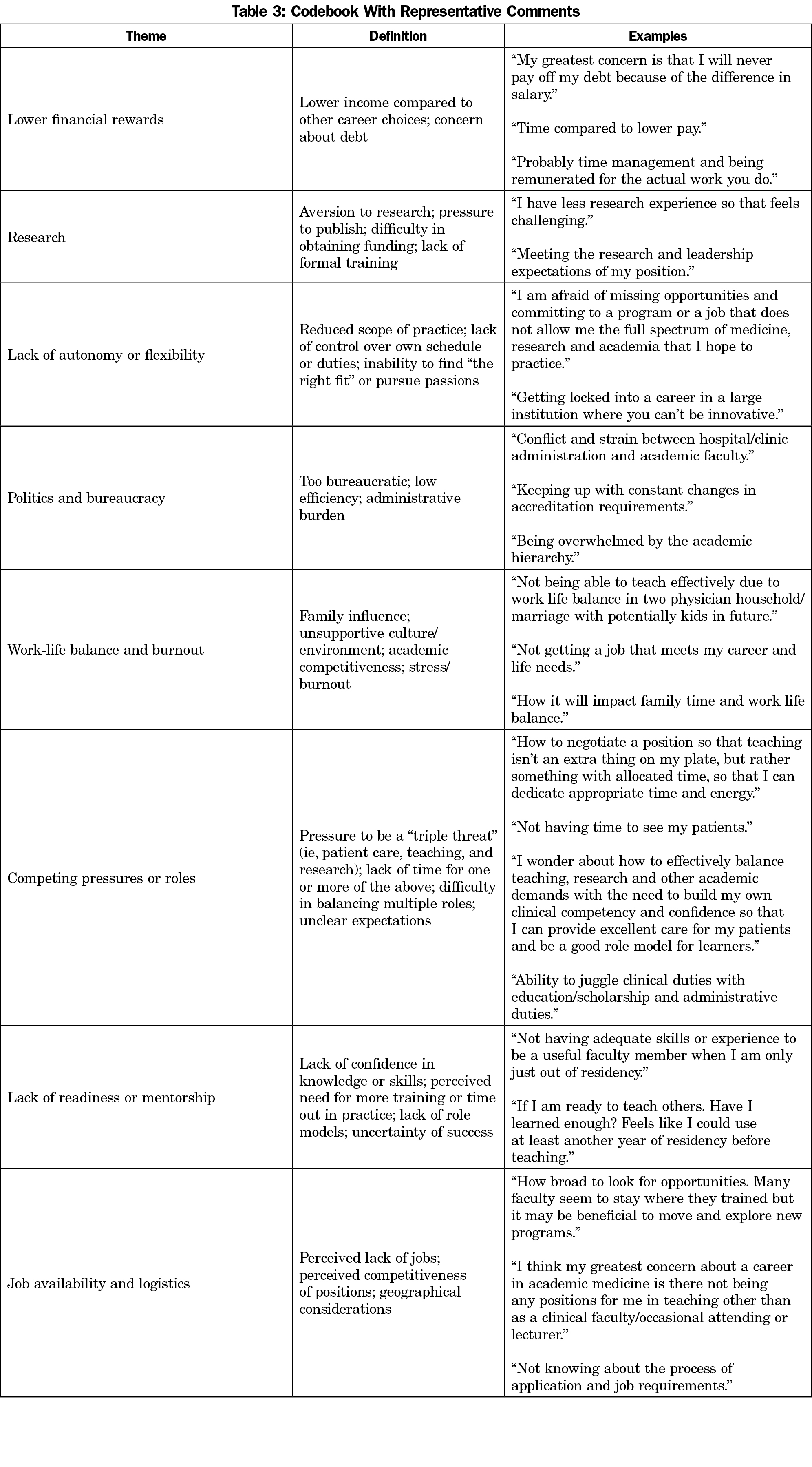

Eight distinct themes emerged from the analysis (Table 3 and Figure 1). Of the 95 individual free responses, 126 codes were assigned. The most frequently recurring theme was lack of readiness or mentorship, which made up nearly one-third (31%) of the codes. The remaining themes were work-life balance and burnout (17%), job availability and logistics (15%), lack of autonomy or flexibility (11%), competing pressures or roles (10%), lower financial rewards (4%), politics and bureaucracy (4%), and research (3%). Interrater reliability was established with a kappa of 0.69.

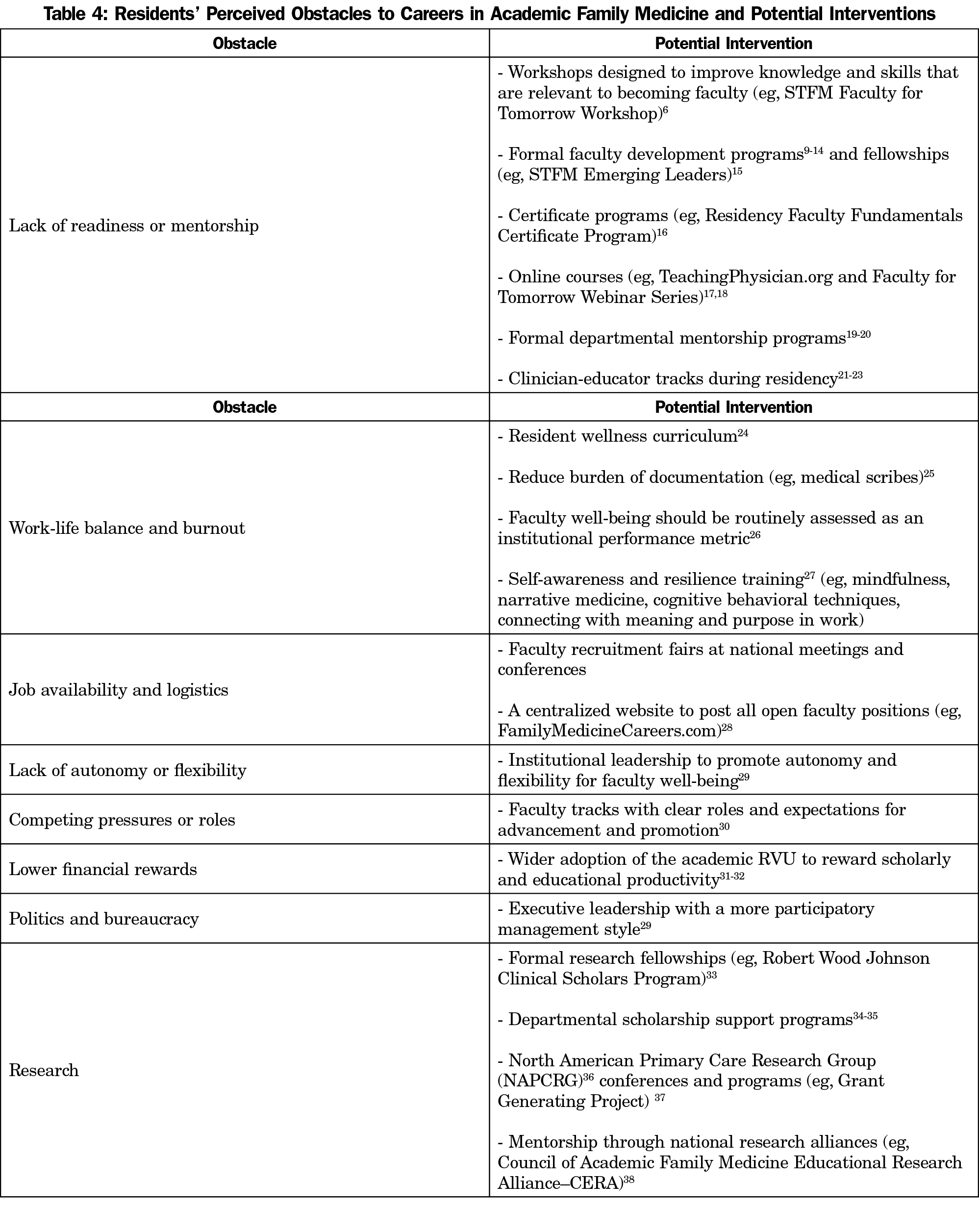

To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify barriers and disincentives to pursuing a career in academic medicine from the perspective of family medicine residents. Our results suggest that there may be at least eight major obstacles, which we summarize and offer potential interventions for in Table 4.9-38

Consistent with prior studies in other specialties,4,5 we found that lack of mentorship was a major disincentive for family medicine residents contemplating academic careers. Formal faculty development programs are likely the most effective type of intervention here, as they have the most evidence in the literature for improving teaching skills, increasing scholarly activities, and advancing young faculty to new leadership roles.9-14 These programs are usually part-time, with participants meeting weekly for 10 to 36 months.9-14

Contrary to prior studies in other specialties suggesting that the largest obstacle is lower financial rewards,4,5 the residents in our study were not as concerned about money. This result seems to be consistent with one study suggesting that family medicine teachers tend to make career decisions based on values other than financial gain.39

Limitations

Although our data draws from a national cohort of residents, the study is still limited by a small sample size. Participants self-selected for interest in academic family medicine; thus, our results may not be generalizable to all residents. Lastly, the wording of our prompt (“What is your greatest concern or fear…”) may have introduced a negative bias, although it did enable us to identify the most pressing challenges and generate a ranked list of concerns.

We identified eight major obstacles for residents who are contemplating academic careers. Each of these obstacles need to be further explored. More research is needed to understand why residents choose, or don’t choose, academic careers.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the members of the STFM Faculty for Tomorrow Task Force: Stoney Abercrombie, Sharon Hull, Paul Larson, Meaghan Ruddy, Cathleen Morrow, Dawn Pruett, Sonya Shipley, Kelly Jones, Stan Kozakowski, and Mary Theobald.

Funding/Support: The Faculty for Tomorrow Task Force is supported by the American Board of Family Medicine Foundation and the STFM Foundation.

Other disclosures: Dr Lin serves on the STFM Board of Directors. Ms Walters is STFM staff. Neither the funders nor the STFM Board of Directors had any role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or the decision to approve publication of the completed manuscript.

References

- Association of Academic Health Centers. Academic Health Center CEOs Say Faculty Shortages Major Problem. http://www.aahcdc.org/Portals/41/Series/Issue-Briefs/Faculty_Shortages_Major_Problem.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed July 5, 2017.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Results of the 2016 Medical School Enrollment Survey. https://members.aamc.org/iweb/upload/Results%20of%20the%202016%20Medical%20School%20Enrollment%20Survey.pdf. Published May 2017. Accessed July 5, 2017.

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. STFM launches initiative in response to faculty shortage. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(3):290-291.

https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1800.

- Borges NJ, Navarro AM, Grover A, Hoban JD. How, when, and why do physicians choose careers in academic medicine? A literature review. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):680-686.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d29cb9.

- Straus SE, Straus C, Tzanetos K; International Campaign to Revitalise Academic Medicine. Career choice in academic medicine: systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(12):1222-1229.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00599.x.

- Lin S, Gordon P. Preparing Residents for Teaching Careers: The Faculty for Tomorrow Resident Workshop. Fam Med. 2017;49(3):225-229.

- Ng S, Lingard L, Kennedy TJ. Qualitative research in medical education: methodologies and methods. In: Swanwick T, ed. Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory and Practice. 2nd ed. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2014:371-384.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book: Academic Year 2015-2016. http://www.acgme.org/About-Us/Publications-and-Resources/Graduate-Medical-Education-Data-Resource-Book. Published 2016. Accessed July 5, 2017.

- Wilkerson L, Uijtdehaage S, Relan A. Increasing the pool of educational leaders for UCLA. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):954-958.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ACM.0000242477.01887.06.

- Muller JH, Irby DM. Developing educational leaders: the teaching scholars program at the University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):959-964.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ACM.0000242588.35354.db.

- Rosenbaum ME, Lenoch S, Ferguson KJ. Increasing departmental and college-wide faculty development opportunities through a teaching scholars program. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):965-968.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ACM.0000242478.12299.c1.

- Steinert Y, McLeod PJ. From novice to informed educator: the teaching scholars program for educators in the health sciences. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):969-974.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ACM.0000242593.29279.be.

- Frohna AZ, Hamstra SJ, Mullan PB, Gruppen LD. Teaching medical education principles and methods to faculty using an active learning approach: the University of Michigan Medical Education Scholars Program. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):975-978.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ACM.0000242573.71314.74.

- Robins L, Ambrozy D, Pinsky LE. Promoting academic excellence through leadership development at the University of Washington: the Teaching Scholars Program. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):979-983.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ACM.0000242584.11488.4e.

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Emerging Leaders Fellowship. http://www.stfm.org/CareerDevelopment/FellowshipsandCertificatePrograms/EmergingLeadersFellowship. Updated 2017. Accessed August 1, 2017.

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Residency Faculty Fundamentals Certificate Program. http://www.stfm.org/CareerDevelopment/FellowshipsandCertificatePrograms/ResidencyFacultyFundamentalsCertificateProgram. Updated 2017. Accessed August 1, 2017.

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Teaching Physician. https://www.teachingphysician.org/. Updated 2017. Accessed August 1, 2017.

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Faculty for Tomorrow Webinars. http://www.stfm.org/OnlineCourses/Webinars/F4T. Updated 2017. Accessed August 1, 2017.

- Riley M, Skye E, Reed BD. Mentorship in an academic department of family medicine. Fam Med. 2014;46(10):792-796.

- Stubbs B, Krueger P, White D, Meaney C, Kwong J, Antao V. Mentorship perceptions and experiences among academic family medicine faculty: findings from a quantitative, comprehensive work-life and leadership survey. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(9):e531-e539.

- Lin S, Sattler A, Chen Yu G, Basaviah P, Schillinger E. Training Future Clinician-Educators: A Track for Family Medicine Residents. Fam Med. 2016;48(3):212-216.

- Heflin MT, Pinheiro S, Kaminetzky CP, McNeill D. ‘So you want to be a clinician-educator...’: designing a clinician-educator curriculum for internal medicine residents. Med Teach. 2009;31(6):e233-e240.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590802516772.

- Smith CC, McCormick I, Huang GC. The clinician-educator track: training internal medicine residents as clinician-educators. Acad Med. 2014;89(6):888-891.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000242.

- Runyan C, Savageau JA, Potts S, Weinreb L. Impact of a family medicine resident wellness curriculum: a feasibility study. Med Educ Online. 2016;21(1):30648.

https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v21.30648.

- Gidwani R, Nguyen C, Kofoed A, et al. Impact of scribes on physician satisfaction, patient satisfaction, and charting efficiency: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):427-433.

https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2122.

- Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. Lancet. 2009;374(9702):1714-1721.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61424-0.

- National Academy of Medicine. Action collaborative on clinician well-being and resilience. https://nam.edu/initiatives/clinician-resilience-and-well-being/. Updated 2017. Accessed August 1, 2017.

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Family Medicine Careers. http://www.familymedicinecareers.com/. Updated 2017. Accessed August 1, 2017.

- Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-146.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004.

- Coleman MM, Richard GV. Faculty career tracks at U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2011;86(8):932-937.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182222699.

- Ma OJ, Hedges JR, Newgard CD. The Academic RVU: Ten Years Developing a Metric for and Financially Incenting Academic Productivity at Oregon Health & Science University. Acad Med. 2017;92(8):1138-1144.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001570.

- Lin S, Mahoney M, Singh B, Schillinger E. An academic achievement calculator for clinician-educators in primary care. Fam Med. 2017;49(8):640-643.

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program. http://rwjcsp.unc.edu/. Updated 2017. Accessed August 1, 2017.

- Viggiano TR, Shub C, Giere RW. The Mayo Clinic’s Clinician-Educator Award: A program to encourage educational innovation and scholarship. Acad Med. 2000;75(9):940-943.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200009000-00018.

- Bertram A, Yeh HC, Bass EB, Brancati F, Levine D, Cofrancesco J Jr. How we developed the GIM clinician-educator mentoring and scholarship program to assist faculty with promotion and scholarly work. Med Teach. 2015;37(2):131-135.

https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.911269.

- North American Primary Care Research Group. http://www.napcrg.org/. Updated 2017. Accessed August 1, 2017.

- North American Primary Care Research Group. Grant Generating Project. http://www.napcrg.org/Programs/GrantGeneratingProject(GGP). Updated 2017. Accessed August 1, 2017.

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. CAFM Educational Research Alliance. http://www.stfm.org/Research/CERA. Updated 2017. Accessed August 1, 2017.

- Simpson DE, Rediske VA, Beecher A, et al. Understanding the careers of physician educators in family medicine. Acad Med. 2001;76(3):259-265.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200103000-00016.

There are no comments for this article.