Nonclinical workers in medical education centers (MECs) play an integral role in the day-to-day operations of the medical education process. The nonclinical workers are faculty (PhD degree holders who do not spend time in clinics), research instructors, and office staff including departmental directors, department administrators, clerkship coordinators, and other medical education coordinators. These workers are frequently the first contact for learners (medical students, residents, and fellows) and spend a significant amount of time with learners. They have multiple roles, carry many responsibilities, and often work in a stressful environment. If nonclinical workers are unsatisfied with their work and are burned out, they may not be in a position to help learners. Long-term exposure to work-related stress1,2 and low job satisfaction3,4 are both associated with burnout. To our knowledge, no study has aimed at identifying burnout rates among nonclinical workers in MECs.

Given the lack of research surrounding nonclinical faculty and staff in MECs and the importance of their role in medical education, the current study sought to fill a gap in the medical education literature. The purpose of this study was threefold: (1) to explore the prevalence of both burnout and job satisfaction among nonclinical workers at the University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita (KUSM-W), (2) to assess relationships between job satisfaction and burnout among nonclinical workers at KUSM-W (a community-based, outpatient and inpatient medical school), and (3) to determine which job satisfaction factors related to burnout. We hypothesized that nonclinical workers with greater job satisfaction experience less emotional exhaustion, less depersonalization, and greater personal accomplishment and therefore, decreased burnout.

The project was a nonexperimental, prospective wellness study involving nonclinical workers at a local MEC. The KUSM-W Institutional Review Board granted exemption for the study. Modified Spector’s Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS)5 and the Abbreviated Maslach Burnout Inventory (AMBI)6,7 were used to measure participants’ job satisfaction and burnout, respectively. Data were gathered via anonymous survey of a convenience sample of all 158 nonclinical workers at a local MEC between December 2016 and January 2017. Given the goal of the study, only nonclinical workers were asked to participate in the study.

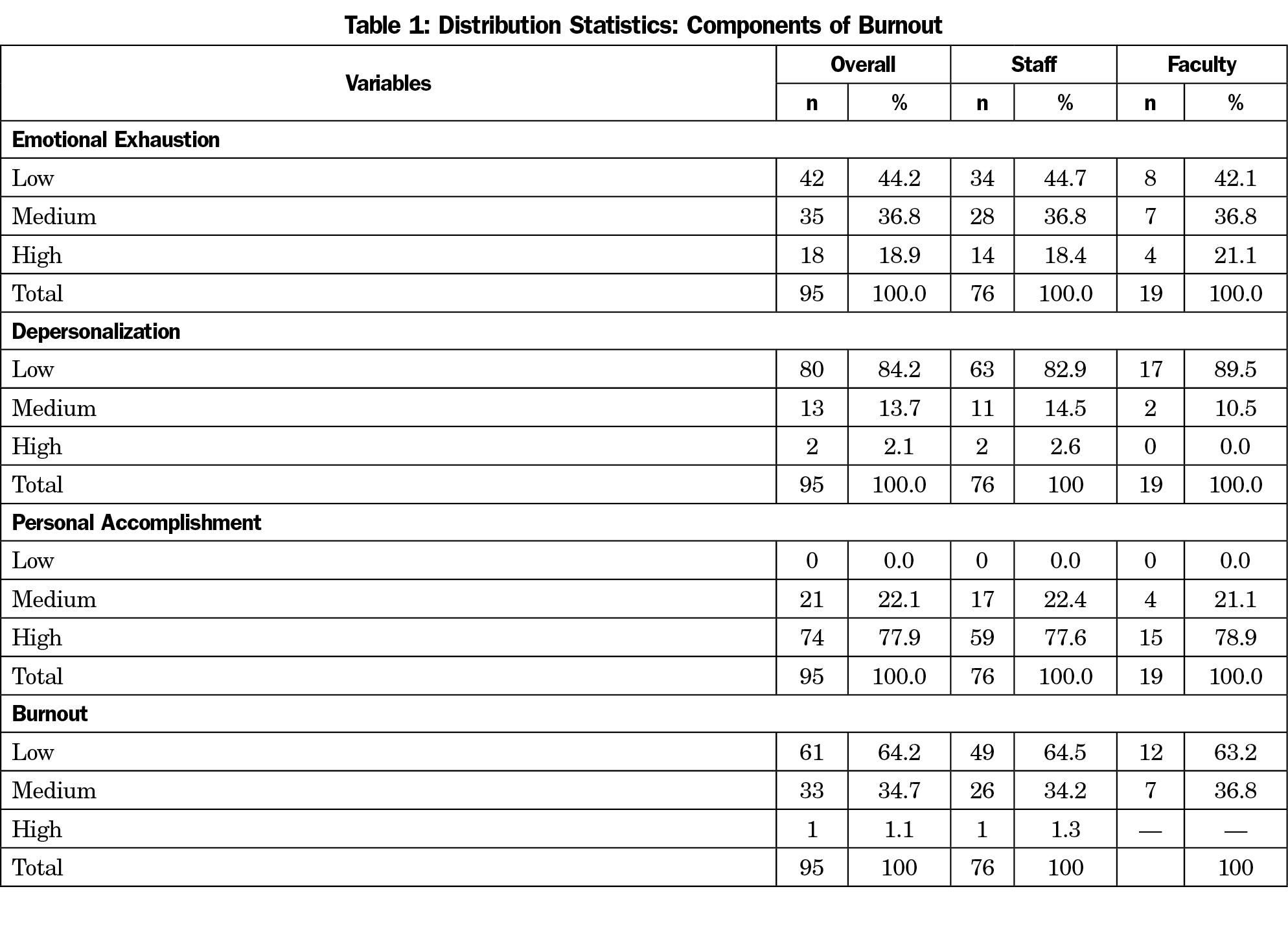

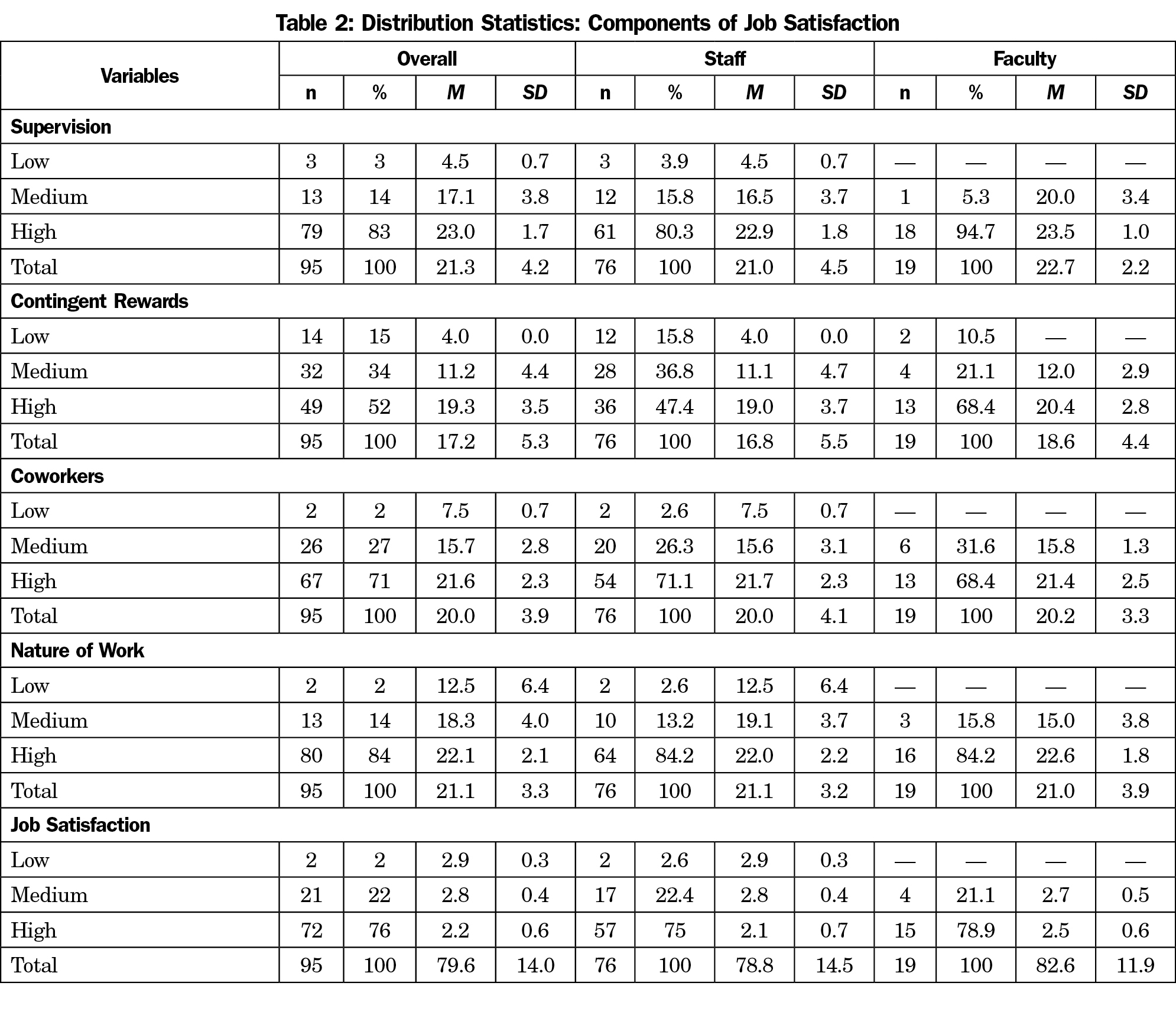

Of the 158 individuals surveyed, data were obtained from 95, representing a 60% response rate. Of the 95 respondents, 80% were staff and 20% were nonclinical faculty. Of those who provided information about their gender, 11% were males while 89% were females. Participants’ years of service to the institution ranged from 3 months to 29 years (7.9±6.9). As shown in Table 1, 1% of nonclinical workers reported high, 35% medium, and 64% low burnout. Sixty-two percent of faculty and 65% of staff reported low burnout respectively. In calculating the prevalence of job satisfaction among the participants, 76% of all respondents, 79% of faculty, and 75% of staff reported high satisfaction rates (Table 2).

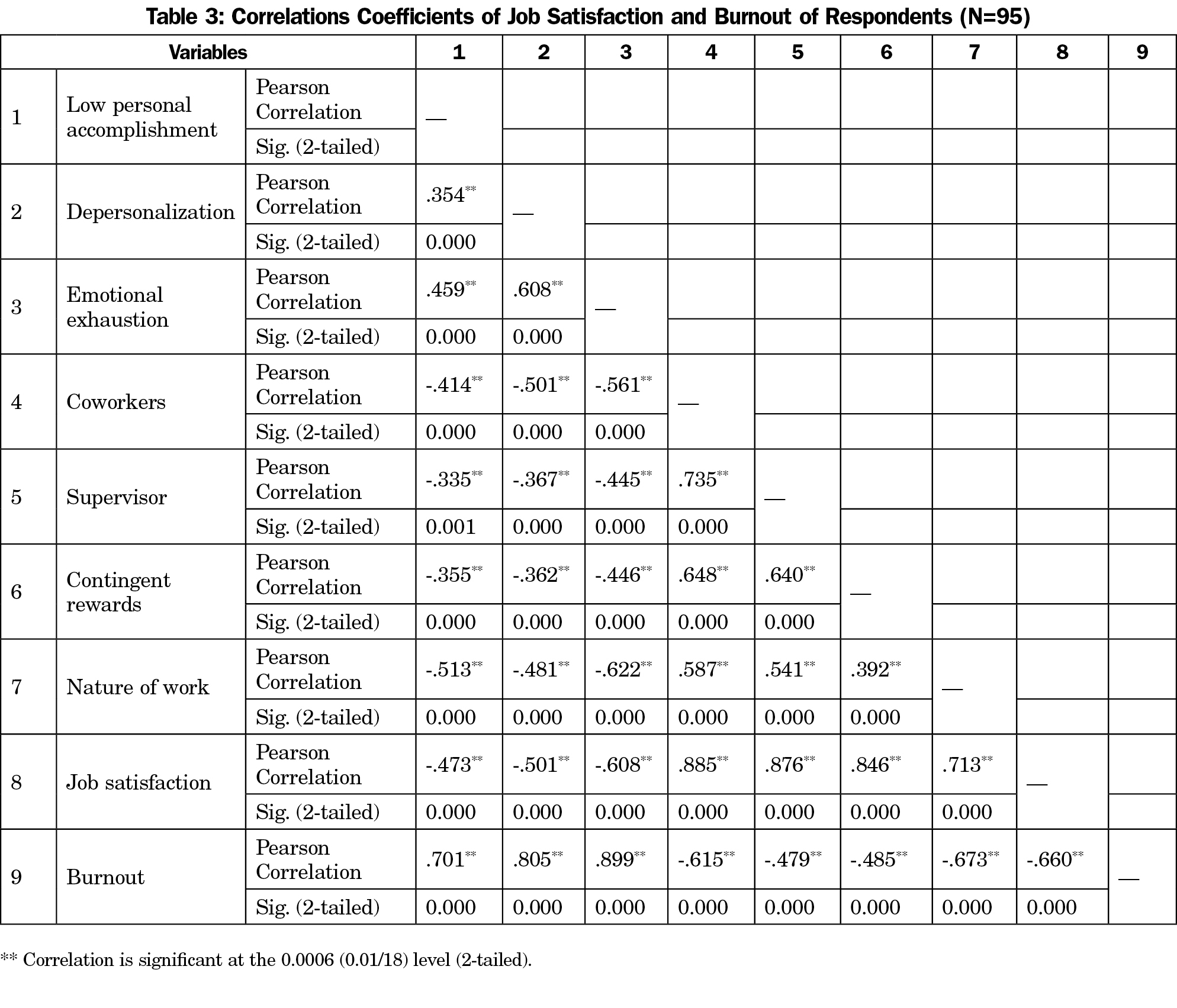

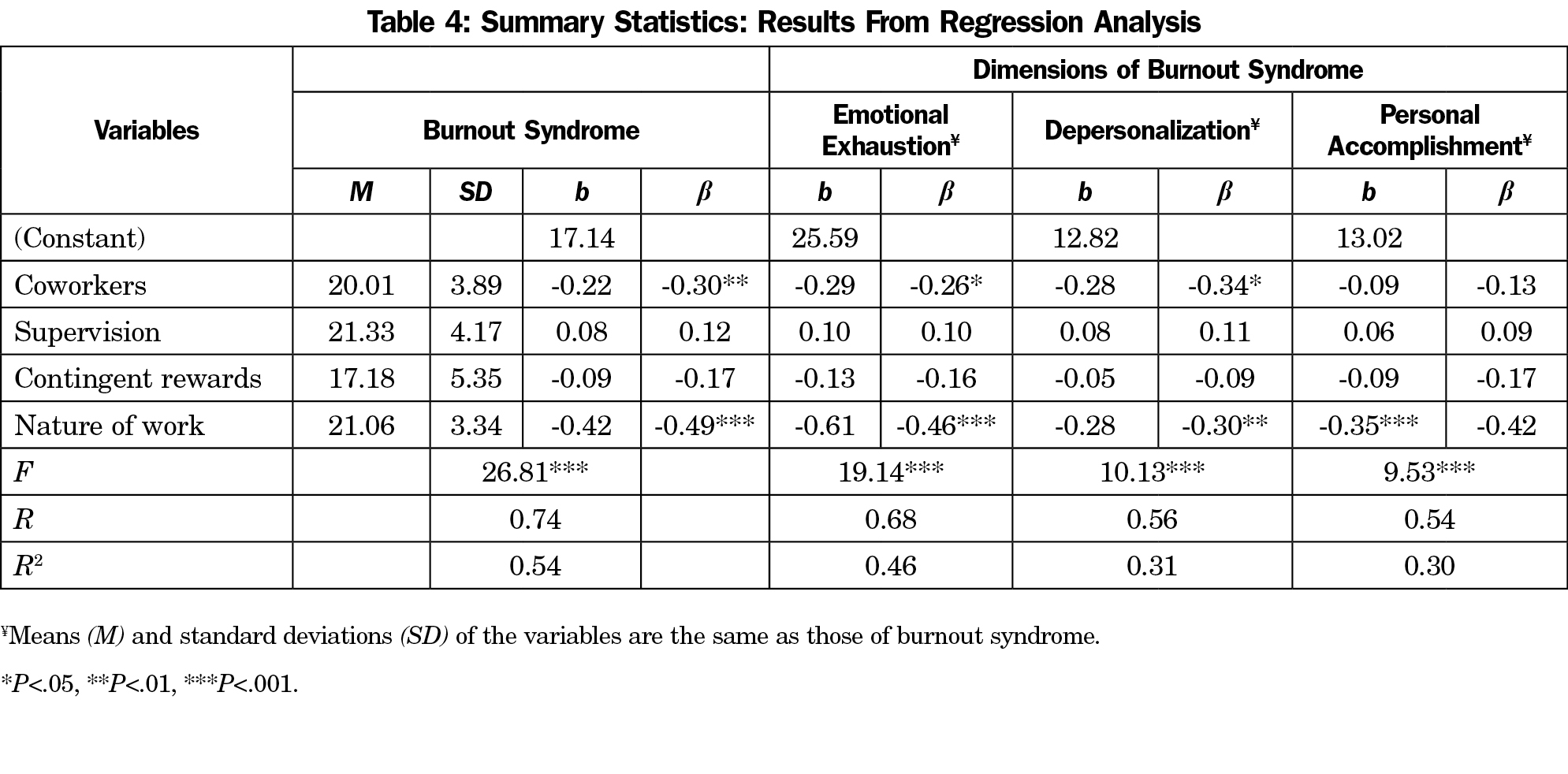

As shown in Table 3, there was a statistically significant relationship between job satisfaction and burnout (r[93]=-.66; P<.001). Multiple regression analysis showed that nature of work (job tasks; b=-.49) and coworkers (b=-.30) were significant predictors of burnout (R=0.74; F[4, 90]=26.81; P<.001; Table 4).

Burnout is a universal problem that affects individuals who work with others in some capacity, and has been found to be getting worse among medical workers.8 More than one-third of our sample reported symptoms of burnout. Despite these concerning statistics, the burnout rates of our sample is better than that of the general population of US workers (excluding physicians), where 53% reported symptoms of burnout.8

Regarding job satisfaction, our findings suggest that the nonclinical workers at a local MEC are satisfied, a finding that is consistent with the Society for Human Resources Management’s 2016 report that showed that 88% of US employees were satisfied with their job.9 Findings emphasized the importance of coworkers, supervision, contingent rewards, and nature of work to job satisfaction.

When it comes to job satisfaction and degrees of burnout, our findings showed that nonclinical workers who are satisfied with their job reported a low degree of burnout. In particular, job satisfaction negatively correlated with all three dimensions of burnout. Although we are not aware of any data that provide a direct comparison to nonclinical workers at MECs, our findings are consistent with studies that examined job satisfaction and burnout among mental health workers10 and other educators.11

Even though there were negative correlations between burnout and all four subscales of job satisfaction, nature of work and coworkers were found to be the best predictors of burnout with negative beta coefficients. These findings suggest that negative feelings about one’s job, poor relationships with colleagues, lack of support, and lack of teamwork from coworkers are all responsible for burnout among nonclinical workers at a local MEC.

This study is limited by having been conducted in a single medical education center, and having a small sample size. The inherent bias and nonprobability-based nature of the convenience sampling limit generalizability of the findings.

The data collected has the potential for many future projects. One consideration would be to expand this study to include multiple institutions with a larger sample. Most literature on burnout and job satisfaction focuses on negative predictive factors and less on what is being done to promote wellbeing and resilience. Given the overall positive outcomes of this data with high rates of job satisfaction and low rates of burnout among the nonclinical workers, more attention should be focused on what is being done to foster optimal functioning at this institution.

In conclusion, the findings of this exploratory study highlight the importance of job satisfaction factors such as nature of work, support from coworkers, supervision, and contingent rewards among nonclinical workers at an MEC. Both job satisfaction and burnout constructs are well studied among clinicians, and are now documented among nonclinical workers at an MEC. This study has contributed new and meaningful knowledge to the field of well-being and resilience among workers at MECs.

There are no comments for this article.