Background and Objectives: Education of health care clinicians on racial and ethnic disparities has primarily focused on emphasizing statistics and cultural competency, with minimal attention to racism. Learning about racism and unconscious processes provides skills that reduce bias when interacting with minority patients. This paper describes the responses to a relationship-based workshop and toolkit highlighting issues that medical educators should address when teaching about racism in the context of pernicious health disparities.

Methods: A multiracial, interdisciplinary team identified essential elements of teaching about racism. A 1.5-hour faculty development workshop consisted of a didactic presentation, a 3-minute video vignette depicting racial and gender microaggression within a hospital setting, small group discussion, large group debrief, and presentation of a toolkit.

Results: One hundred twenty diverse participants attended the workshop at the 2016 Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference. Qualitative information from small group facilitators and large group discussions identified some participants’ emotional reactions to the video including dismay, anger, fear, and shame. A pre/postsurvey (N=72) revealed significant changes in attitude and knowledge regarding issues of racism and in participants’ personal commitment to address them.

Discussion: Results suggest that this workshop changed knowledge and attitudes about racism and health inequities. Findings also suggest this workshop improved confidence in teaching learners to reduce racism in patient care. The authors recommend that curricula continue to be developed and disseminated nationally to equip faculty with the skills and teaching resources to effectively incorporate the discussion of racism into the education of health professionals.

Despite efforts to promote health equity over the past 30 years, significant racial and ethnic disparities persist.1 Racial and ethnic minorities continue to be disproportionately affected by disparities in disease.2,3 Structural and personally-mediated racism increasingly emerge as drivers of these inequities as they impact social, economic, and environmental factors, health care delivery, and clinician behavior.4-12

Teaching clinicians about health care inequities has primarily focused on disparity statistics, power analyses, and cultural competence training.13,14 These strategies, however, have proved insufficient to reach health equity, as they address the symptoms while neglecting how racism helps create inequities and do not challenge the institutional and personal behaviors that sustain them.15-18 While teaching health care professionals about racism reduces biases,8,19-23 few curricula for medical education exist.20-23 Therefore, a workshop and toolkit to help medical educators teach and address racism was created and presented at the 2016 Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) Annual Spring Conference.

Members from the STFM Group on Minority/Multicultural Health organically formed a multiracial, multidisciplinary team to develop a curriculum for educators to address racism as a key social determinant of health. Using transcripts of group electronic discussions, this team identified essential curricular themes (see Table 1) using Jones’ Tripartite Model as a framework for exploring levels of racism (institutional, personally-mediated, and internalized).24 The team created a relationship-based faculty development workshop and accompanying toolkit.

The 90-minute workshop consisted of a didactic presentation on the connections between racism and health inequity, a video vignette developed by the team, small group discussion, large group debrief, and a commitment activity. The toolkit included articles, books, podcasts, videos, websites, and activities which explore racism, implicit bias, privilege, and the intersectionality of identities that could be used in participants’ settings.25 Workshop materials are available at the STFM Resource Library (https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/search?executeSearch=true&SearchTerm=racism&l=1).

The presentation summarized how discrimination, bias, and racism affect Americans, and the applicability of Jones’ model to poor health outcomes.24 Participants then viewed a 3-minute video depicting an inpatient family medicine team rounding outside the room of a patient presenting with a gunshot wound. A supervising white male physician speaks disparagingly about the patient, presumes he is Latino and a gang member, and simultaneously is condescending to an African American, female intern who is further undermined by a white male senior resident.26

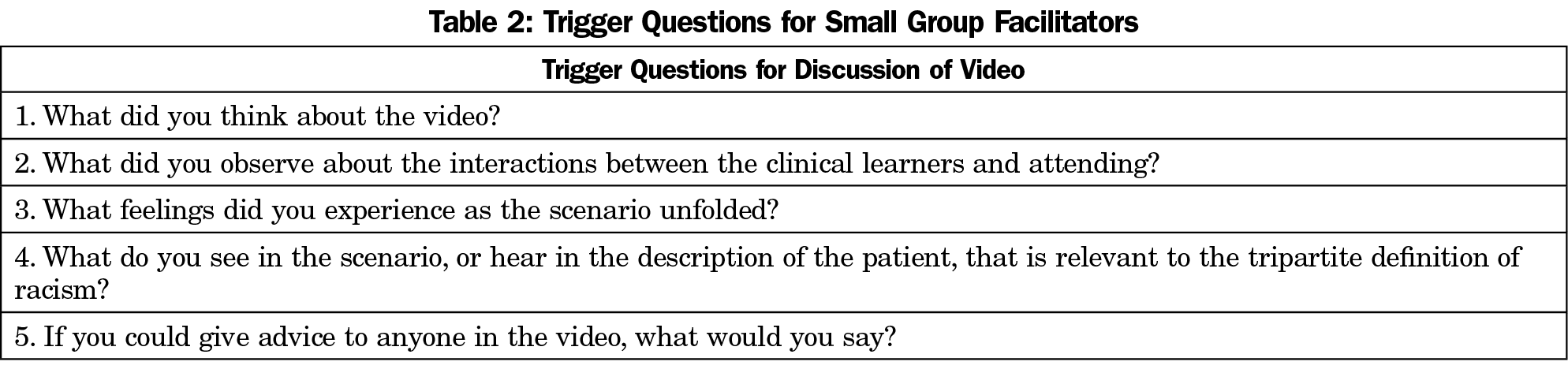

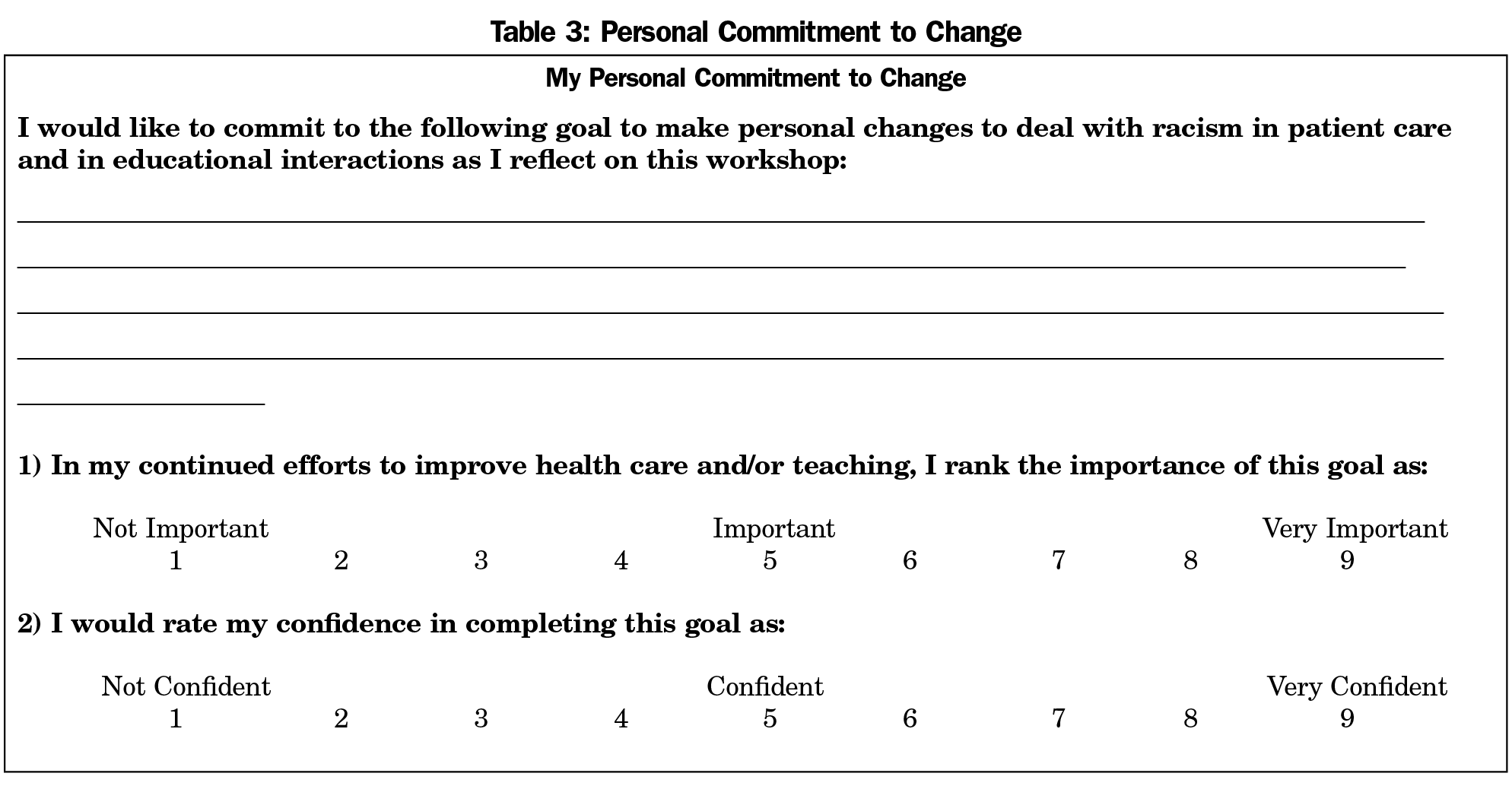

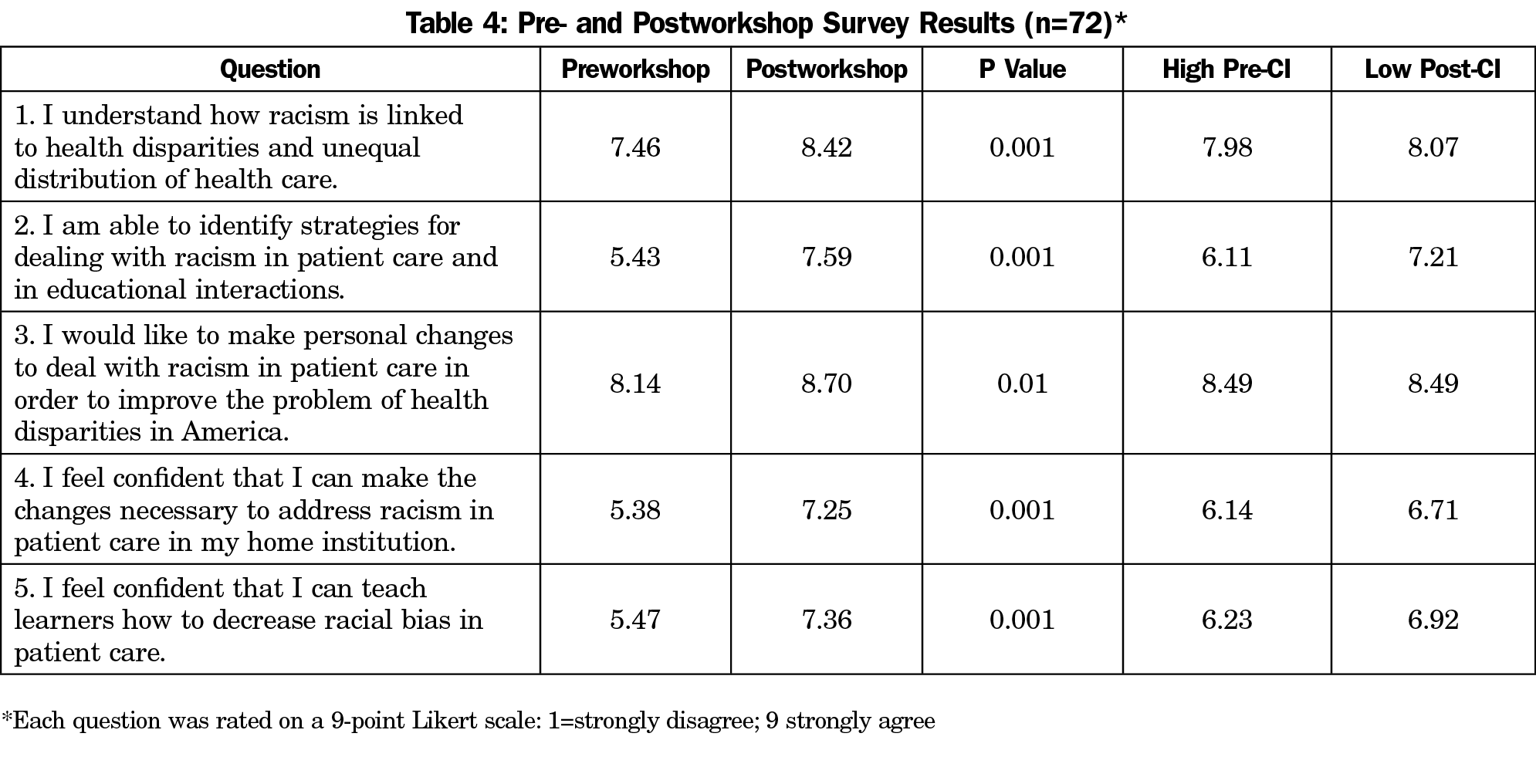

Workshop faculty divided participants into groups of ten and facilitated discussions using standardized questions (Table 2). Participants then shared their discussions in a large group debrief. The educator resource toolkit was then presented. Finally, participants wrote one action they would take to address racism in their home institutions and rated their confidence in following through (Table 3). Participants were instructed to keep and review this commitment in 6 months. An anonymous pre- and postworkshop survey was administered to assess any change in participants’ knowledge and attitudes (Table 4). Faculty facilitators recorded issues discussed in small groups, which were later analyzed by a team member for recurrent themes. This project was classified as exempt by Montefiore Medical Center IRB.

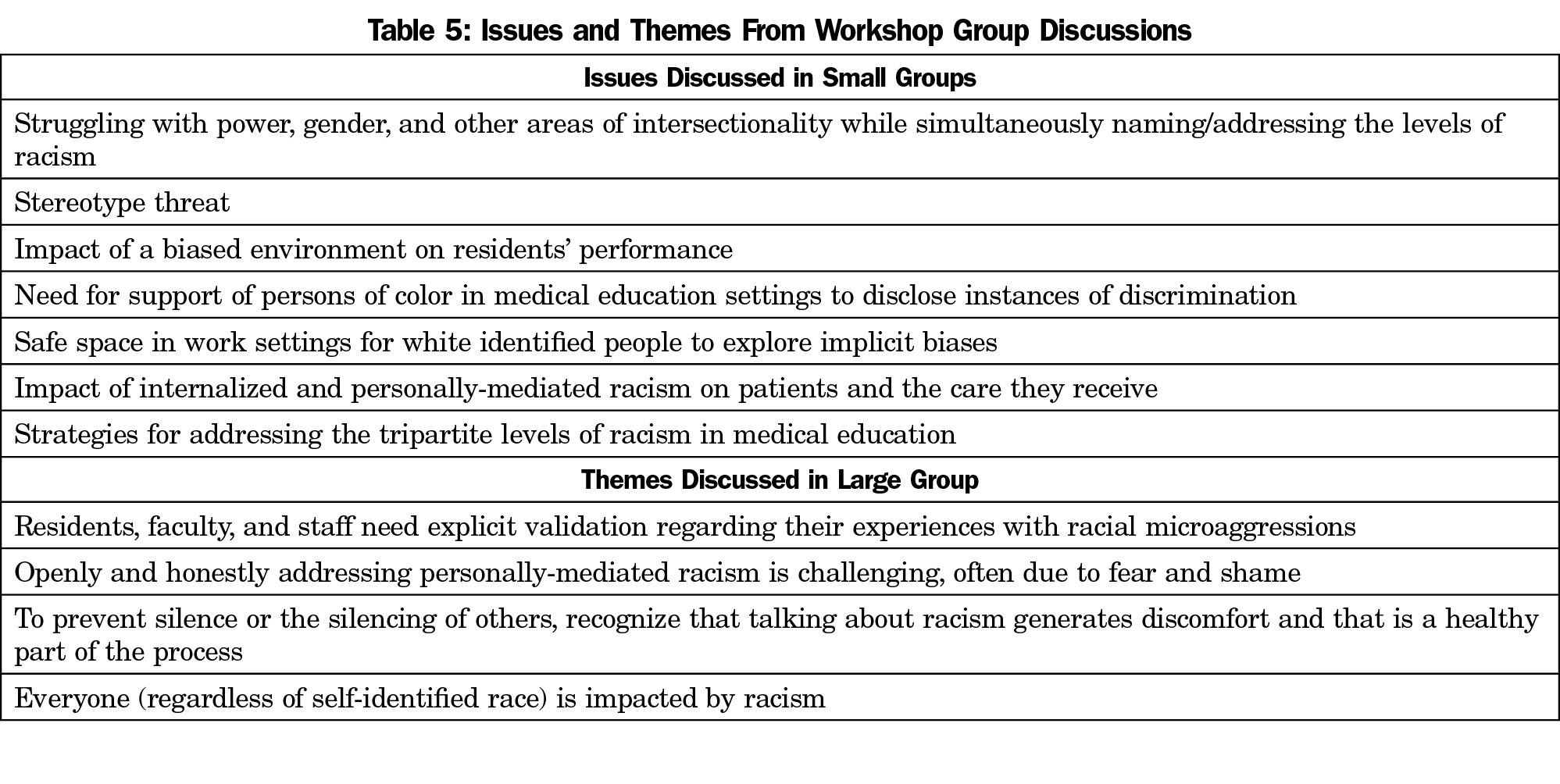

One hundred twenty participants attended this workshop, as determined by count from three facilitators. Demographic information was not collected for workshop participants, but the participants appeared diverse in many respects. The team reviewed facilitators’ notes on small and large group discussions to identify themes. Facilitator notes revealed that small groups began with reactions to the video’s content. Some groups moved to an affective level, while others had cognitive discussions about scenarios and strategies. Some participants expressed feeling dismay, anger, fear, and shame. Various issues were discussed (Table 5), and some participants expressed wanting more time for deeper discussion than time allowed. In the large group debrief, when asked to raise their hands, a majority of participants endorsed feeling discomfort during the small group process. However, many said they were able to “push through it.” Some participants had powerful emotional connections to the content; some became tearful, yet simultaneously expressed finding the experience beneficial. Four notable themes emerged in the large group debriefing (Table 5).

The pre/postsurvey was completed by 72 participants and analyzed in aggregate (Table 4). Results revealed that participants improved their knowledge of the impact of racism on health inequities (Q1, P=0.001) and of strategies to address racism in home institutions (Q2, P=0.001). Participants had higher levels of confidence in making strategies to improve the racial climate in their institutions (Q4, P=0.001) and in teaching learners to reduce racism in patient care (Q5, P=0.001). Finally, participants highly rated their commitment to make personal changes in addressing health disparities (Q3, P=0.01).

This relationship-based workshop and toolkit are early steps in developing an antiracism curriculum in medical education, and demonstrate how providing information and relational context for difficult conversations can engage faculty to consider addressing racism in their educational institutions. Survey results showed that participants felt they had changed or improved their knowledge of how to address these issues.

Limitations

Participants selected this workshop, and demographic information was not collected, which limits generalizability. Due to underestimating the number of participants, only 80 paper copies of the survey were distributed, and 72 were completed. The survey results may not truly reflect the entire group experience. The lack of a control group calls into question whether attitude changes were attributable solely to information presented in the workshop. Additionally, qualitative information from group discussions were collected via group facilitators, who were presenters and also authors of this study, which may introduce bias.

Health inequities are not inevitable.27 Given the evidence on the role of racial bias in disparate health outcomes, racism must be included in medical education curricula.5,8,13,29 This workshop offers preliminary evidence that educators can benefit from exploring racism in medical education. Training programs should: (1) prepare health professionals to address racism; (2) adhere to the health inequities training requirements of the Association of American Medical Colleges and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; and (3) develop innovative, impactful, relationship-based curricula that are facilitated with thoughtfulness and respect by well-prepared faculty members. Educating future health care professionals to combat racism is essential in eliminating health inequities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the work and dedication of other members of their team whose powerful contribution to the development and implementation of the aforementioned workshop lead to its success. Those members include: Denise Rodgers, MD, David Henderson, MD, Warren Ferguson, MD, Lamercie Saint-Hilaire, MD, and Diana Wu, MD. The authors send a special thank you to Mindy Smith, who provided valuable editorial guidance to their team.

Presentations: This manuscript describes part of a workshop presentation given at the 2016 Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Meeting, in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Thirty Years Later, the “Heckler Report” continues to influence efforts to improve minority health. https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/OMH/OMH-HecklerReport.html. Accessed August, 2016

- Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: understanding racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2002.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). 2016 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; July 2017. AHRQ Pub. No. 17-0001. http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr16/index.html Accessed September 2017.

- Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X.

- Blair IV, Steiner JF, Fairclough DL, et al. Clinicians’ implicit ethnic/racial bias and perceptions of care among Black and Latino patients. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):43-52. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1442.

- Wyatt SB, Williams DR, Calvin R, Henderson FC, Walker ER, Winters K. Racism and cardiovascular disease in African Americans. Am J Med Sci. 2003;325(6):315-331. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000441-200306000-00003.

- Harrell JP, Hall S, Taliaferro J. Physiological responses to racism and discrimination: an assessment of the evidence. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):243-248. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.2.243.

- Lukachko A, Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM. Structural racism and myocardial infarction in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:42-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.021.

- McCluney CL, Schmitz LL, Hicken MT, Sonnega A. Structural racism in the workplace: does perception matter for health inequalities? Soc Sci Med.1-9. in press.

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Racism and health I: pathways and scientific evidence. Am Behav Sci. 2013;57(8):1-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213487340.

- van Ryn M, Burgess DJ, Dovidio JF, et al. The impact of racism on clinician cognition, behavior and clinical decision making. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8:199-218.2011. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X11000191.

- Hannan EL, van Ryn M, Burke J, et al. Access to coronary artery bypass surgery by race/ethnicity and gender among patients who are appropriate for surgery. Med Care. 1999;37(1):68-77. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199901000-00010.

- Carty DC, Kruger DJ, Turner TM, Campbell B, DeLoney EH, Lewis EY. Racism, health status, and birth outcomes: results of a participatory community-based intervention and health survey. J Urban Health. 2011;88(1):84-97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-010-9530-9.

- Loue S, Wilson-Delfosse A, Limbach K. Identifying gaps in the cultural competence/sensitivity components of an undergraduate medical school curriculum: a needs assessment. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(5):1412-1419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0102-z.

- Stone J, Moskowitz GB. Non-conscious bias in medical decision making: what can be done to reduce it? Med Educ. 2011;45(8):768-776. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04026.x.

- Bellack JP. Unconscious bias: an obstacle to cultural competence. J Nurs Educ. 2015;54(9):S63-S64. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20150814-12.

- Brooks KC. A piece of my mind. A silent curriculum. JAMA. 2015;313(19):1909-1910. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.1676.

- Kumagai AK, Lypson ML. Beyond cultural competence: critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Acad Med. 2009;84(6):782-787. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a42398.

- Ring J, Nyquist JG, Mitchell S. Curriculum for culturally responsive health care: the step-by-step guide for cultural competence training. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing; 2008.

- Acosta D, Ackerman-Barger K. Breaking the silence: time to talk about race and racism. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):285-288. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001416.

- Hannah SD, Carpenter-Song E. Patrolling your blind spots: introspection and public catharsis in a medical school faculty development course to reduce unconscious bias in medicine. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2013;37:314-339.1-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-013-9320-4.

- Sharma M, Pinto AD, Kumagai AK. Teaching the social determinants of health: a path to equity or a road to nowhere? Acad Med. 2018;93(1):25-30.

- van Ryn M, Saha S. Exploring unconscious bias in disparities research and medical education. JAMA. 2011;306(9):995-996. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1275.

- Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212-1215. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.90.8.1212.

- Brown-Speights JS, Edgoose J, Ferguson W, et al. Teaching about racism in the context of persistent health and healthcare disparities: How educators can enlighten themselves and their learners. Presented at the Society for Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference; April 30-May 4, Minneapolis, MN.

- Henderson D. Trigger Video for Small Group Activity on Implicit Bias. In: Henderson D. Teaching About Racism in the Context of Persistent Health and Healthcare Disparities: How Educators Can Enlighten Themselves and Their Learners. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/search?executeSearch=true&SearchTerm=racism&l=1. p. 15. Accessed June 2016.

- Fry-Johnson YW, Levine R, Rowley D, Agboto V, Rust G. United States black:white infant mortality disparities are not inevitable: identification of community resilience independent of socioeconomic status. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(1)(suppl 1):S1-S131, 5.

- Holm AL, Rowe Gorosh M, Brady M, White-Perkins D. Recognizing Privilege and Bias: An Interactive Exercise to Expand Health Care Providers’ Personal Awareness. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):360-364. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001290.

- Smedley BD. The lived experience of race and its health consequences. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):933-935. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300643.

There are no comments for this article.