Background and Objectives: Burnout rates among American physicians and trainees are high. The objectives of this study were: (1) to compare burnout rates among residents and faculty members of the graduate medical education (GME) programs sponsored by the University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita (KUSM-W) to previously published data, and (2) to evaluate the physicians’ feedback on perceived causes and activities to promote wellness.

Methods: Between April and May 2017, we surveyed 439 residents and core faculty members from 13 residency programs sponsored by the KUSM-W. The survey included the Abbreviated Maslach Burnout Inventory, two open-ended questions, and demographic questions. The authors used Kruskal-Wallis and Fisher exact tests to analyze the quantitative data, and an immersion-crystallization approach to analyze the open-ended data.

Results: Forty-three percent of all respondents met the criteria for burnout, and the overall response rate was 50%. When compared with core faculty members, rates of burnout among residents were higher (51% vs 31%, P<.05). The immersion-crystallization approach revealed five interconnected themes as possible causes of burnout among physicians: work-life imbalance, system issues, poor morale, difficult patient populations, and unrealistic expectations. Promotion of healthy and mindfulness activities; enhanced program leadership; and administration, program, and system modification were identified as activities/resources that can promote wellness among physicians.

Conclusions: The findings show that burnout is prevalent among physicians within GME. Wellness and burnout prevention should be addressed at the beginning of medical training and longitudinally. Potential intervention should include activities that allow physicians to thrive in the health care environment.

Burnout among health care professionals has been associated with a decrease in the quality of patient care,1-3 an increase in the number of medical errors,4,5 and an increase in the risk of suicidal ideation, depression, and substance abuse.6,7 Health care professionals experiencing burnout also have a stronger intention of leaving the medical profession via early retirement and/or career change.8,9 Shanafelt and colleagues’ work documented increasing rates of burnout among all specialties studied between the years of 2011 and 2014.10 The impact of burnout on undergraduate medical education and graduate medical education (GME) has clarified that burnout begins early in the medical school experience7 and extends throughout GME. Publications in the lay press have called attention to the impact of burnout within GME, increasing public awareness of the toll burnout has on residents in training.11 The focus on addressing wellness within GME has been further codified by the inclusion of wellness initiatives with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s (ACGME) revision of Section VI of the Common Program Requirements.12

Our community-based medical campus sponsors 12 residency programs and one fellowship program, containing 280 residents. The purpose of this study was threefold: (1) to evaluate the level of burnout among both resident and faculty members of the GME programs sponsored by the University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita (KUSM-W); (2) to understand how the burnout rates among our residents and core faculty (as listed in ACGME Accreditation Data System [ADS]) compared to the previously published data7,10; and (3) to evaluate the participants’ opinions of the causes of burnout among their colleagues, and the solutions that they viewed as necessary to affect a positive change in their burnout experience.

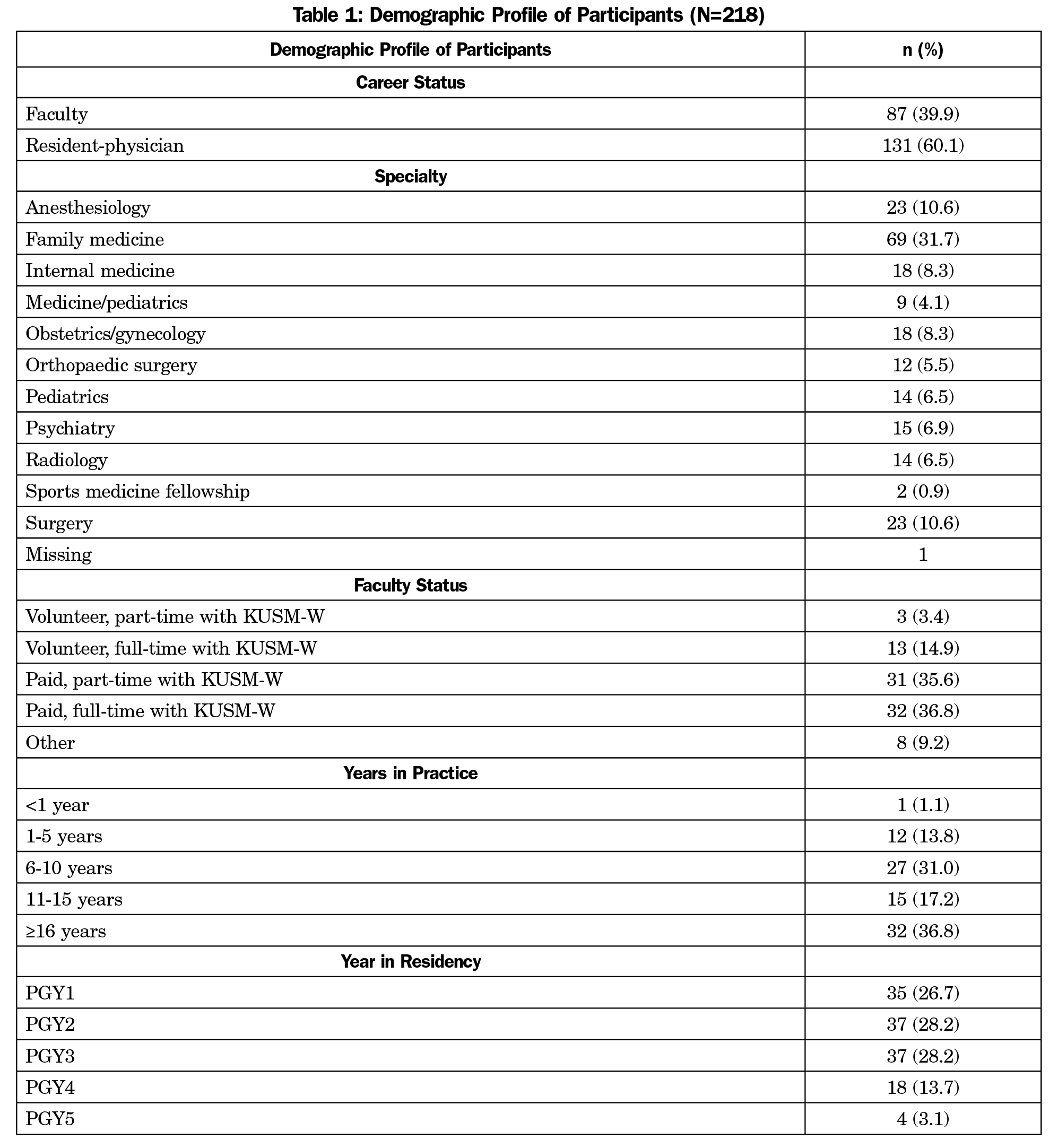

In April and May 2017, we surveyed 439 residents and core faculty members from 13 residency programs sponsored by KUSM-W. Each resident and faculty received an email invitation to participate along with a link to a survey. The survey included items from the Abbreviated Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI-9), two open-ended questions, and demographic information (career status, specialty, faculty status, years in practice, and year in residency). The KUSM-W Institutional Review Board granted an exemption for the study.

The MBI-9 is a validated nine-item questionnaire considered a criterion to measure manifestations of burnout.14-19 The survey included two open-ended questions to elicit the physicians’ feedback on perceived causes of burnout and activities to promote wellness. The question “In your opinion, what are some of the causes of burnout among your peers?” was used to elicit the participants’ perceived causes of burnout. The question, “What resources and/or activities would help professionals like you to promote wellness?” was used to identify possible resources and activities deemed helpful in promoting wellness among physicians.

Standard descriptive statistics, Fisher exact test, and Kruskal-Wallis test were used to analyze the quantitative data. The study team analyzed the content of the open-ended responses (qualitative data) individually and in two team meetings using an immersion-crystallization approach20-22 —a dual process involving detailed review of textual data and momentarily suspending the immersion process to reflect on emerging findings until consistent themes are identified.20,21

Quantitative Results

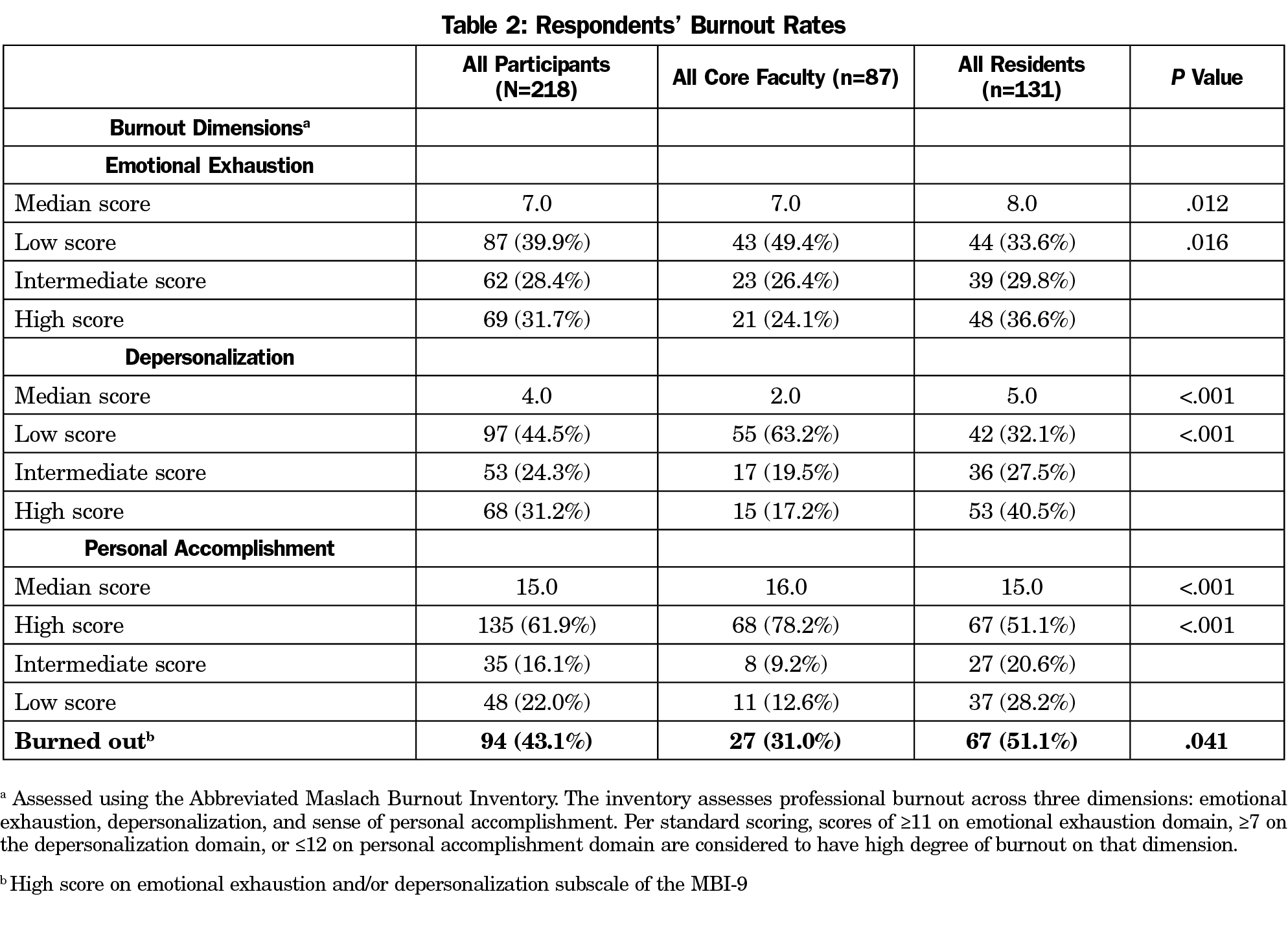

The response rates were 50% (218/439) for all participants, 55% (87/159) for core faculty, and 47% (131/280) for residents. As shown in Table 1, 87 (40%) of the respondents were core faculty and 131 (60%) were residents. Sixty-nine (32%) respondents were from the family medicine specialty, and 32 (37%) of the core faculty were full time, and paid by the sponsoring institution. Using the MBI-9 for assessment, 32% of all respondents had high emotional exhaustion, 31% high depersonalization, and 22% low personal accomplishment (Table 2). In aggregate, 43% of all respondents met the criteria for burnout (Table 2). When compared with core faculty members, rates of burnout among residents were higher (51% vs 31%, P<.05; Table 2).

Qualitative Results: Causes of Burnout

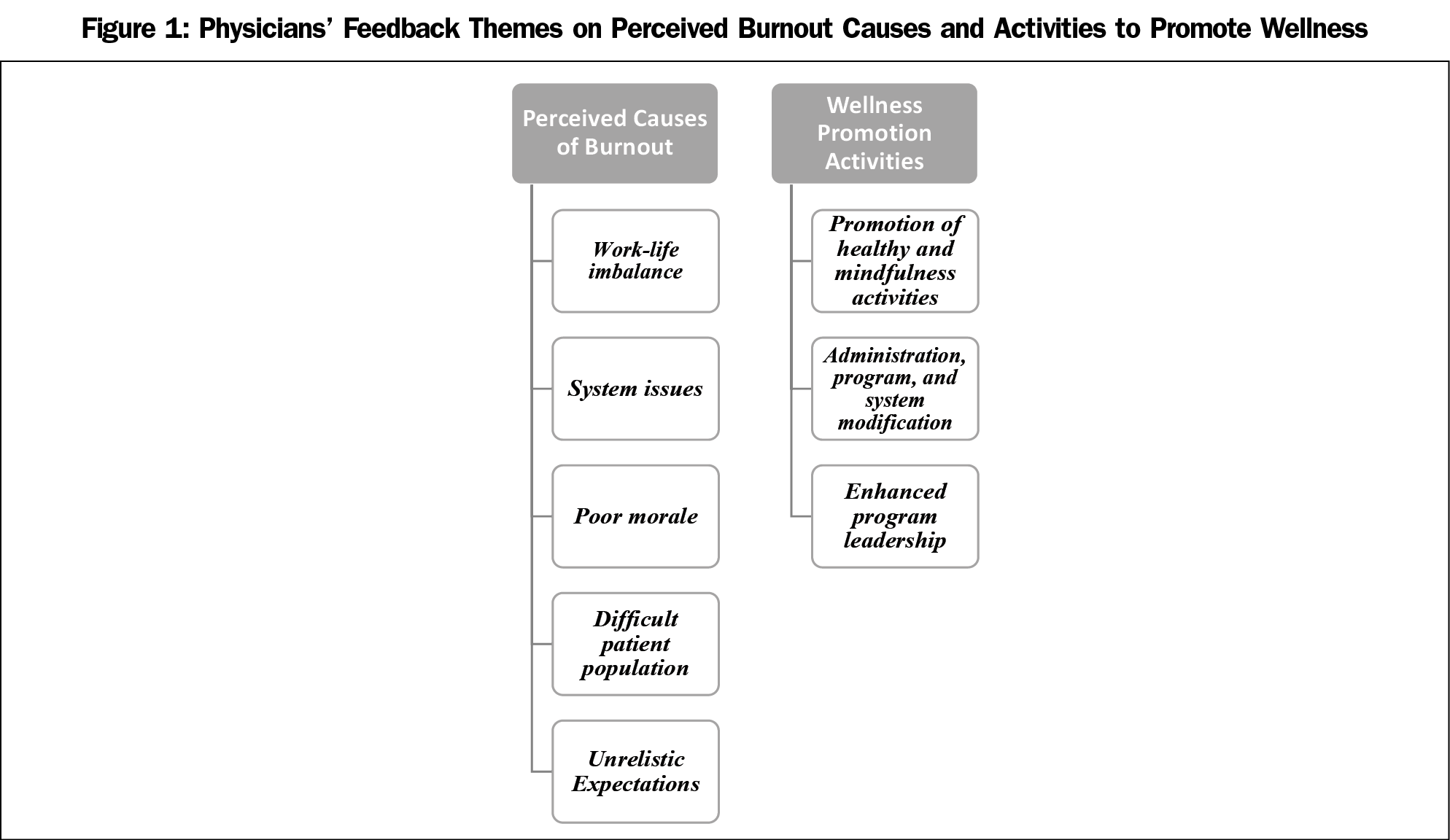

Of the 218 participants, 74% provided responses to the possible causes of burnout question. Five themes emerged as possible causes of burnout among physicians: work-life imbalance, system issues, poor morale, difficult patient populations, and unrealistic expectations (Table 3; Figure 1).

Qualitative Results: Wellness Promotion

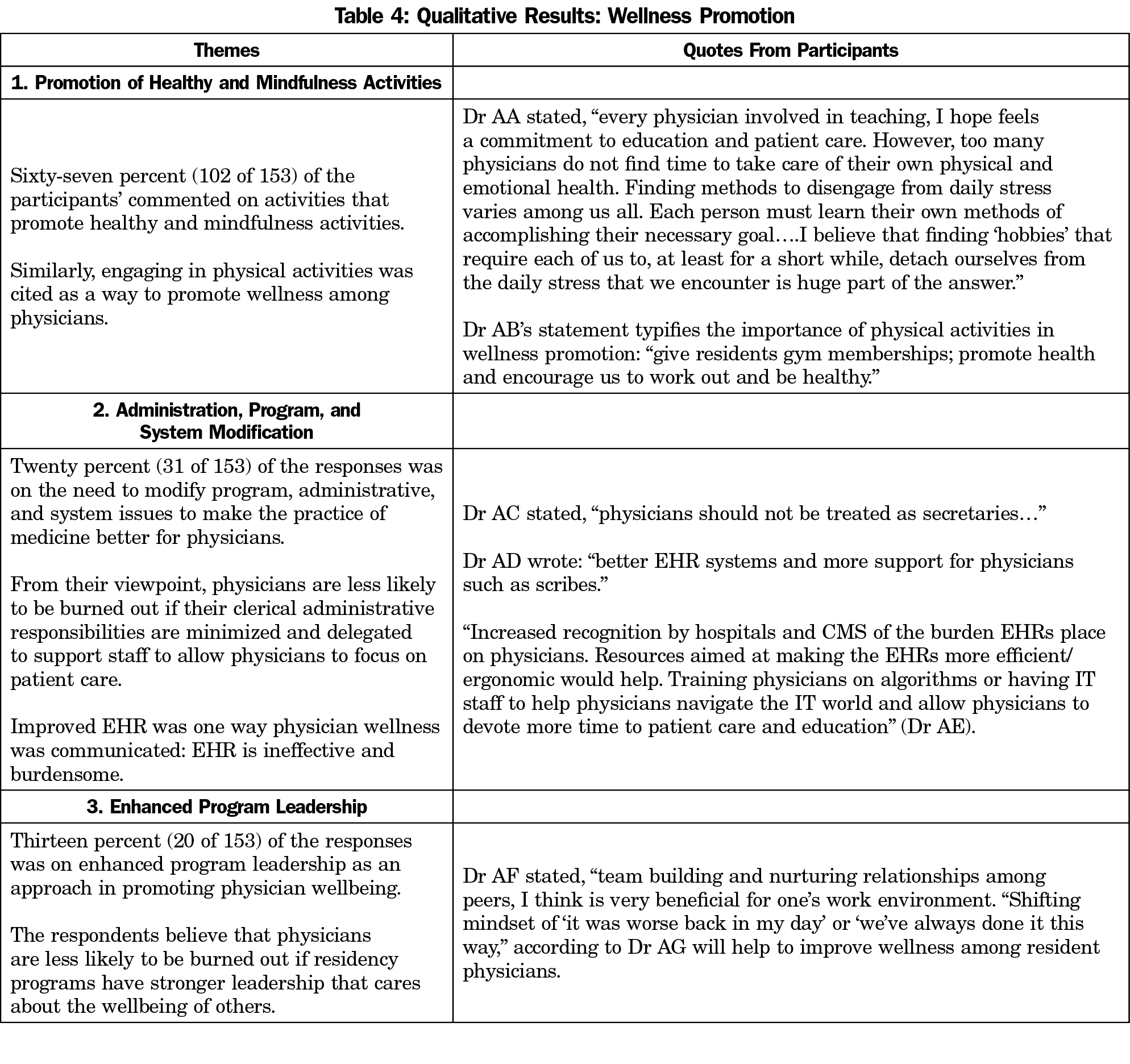

Sixty-three percent of the 218 participants provided responses to the wellness promotion question. Three themes emerged as activities and resources that can promote wellness among physicians: promotion of healthy and mindfulness activities; enhanced program leadership; and administration, program, and system modification (Table 4; Figure 1).

This study illustrates burnout rates within GME programs sponsored by a community-based medical school. As 12 of the 13 sponsored programs are core rather than fellowships, these burnout rates of all participants further illustrate Shanafelt’s data regarding burnout risk in front-line specialties.10 While our data correspond with previously published data, there are notable differences. The faculty burnout rate of 31% is lower than other published burnout rates among practicing physicians.10,18 Within the community-based GME model in our institution, the faculty are active in clinical responsibilities and patient care as well as academic responsibilities including teaching, supervision, and scholarly activities. Whether these academic activities impact the experience of burnout were not addressed in this study. Additionally, the residents’ contribution to patient care, including much of the clinical charting, orders, and medication reconciliation lessens the EHR and clerical burden upon the faculty. Though the residents’ overall burnout rate of 51% is lower than the reported 60% among US residents/fellows,7 it nonetheless validates the call to understand and address the residents’ experience of burnout within GME programs.12

The qualitative data provide insight into resident and teaching faculty’s personal experiences. These insights reveal significant angst within the GME system to provide quality care for patients while having little time for self and family needs. The novel findings regarding poor morale and system issues display an opinion of leadership and systems augmenting the problem rather than addressing the experience of burnout. Compassion fatigue is evident in findings regarding the difficult patient population. The qualitative data captured participant input regarding ideas to promote greater wellness, which is consistent with the National Academy of Medicine’s (NAM) burnout framework aimed at promoting well-being and resilience among physicians.23 Comments illustrated recognition of the need for actions on the part of the individual, engaging in exercise, healthier diet, and decompression from the daily stress. Comments also expressed the need for administrative and system modification including enhanced leadership. Suggested action items also imply the need for more resources within hospital and institutional systems.

This study has a number of limitations. First, as this study’s results are limited to the 13 community-based residency programs sponsored by a single Midwest medical school, the findings may not be generalizable to other areas. Second, there is possibility of response bias with the response rate of 50%. However, the small response rate is consistent with other studies on physicians and residents.7,10 Third, given the size of our program we could not report specialty programs’ burnout scores without compromising anonymity.

In conclusion, burnout was prevalent among residents and core faculty within a GME system with multifactorial and interwoven themes. The high burnout rates combined with the qualitative insights on possible cause of burnout within the GME environment require serious intervention. Potential intervention should incorporate the NAM burnout framework. Medical trainees should be educated on the business of becoming physicians (workload, Medicare, billing, relationships with administration, etc) while also understanding the very real emotional toll and the need for resiliency training (diet, exercise, time for decompression, etc). Given that poor morale as a possible cause of burnout, intervention should include developing more authentic relationships among faculty and trainees. Residents must feel free to ask for help, whether clinical or personal without fear of showing weakness. Health system recognition of the value of GME should include tangible demonstration of this recognition.

References

- Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Trojanowski L. The relationship between physician burnout and quality of healthcare in terms of safety and acceptability: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e015141. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015141

- Weigl M, Schneider A, Hoffmann F, Angerer P. Work stress, burnout, and perceived quality of care: a cross-sectional study among hospital pediatricians. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174(9):1237-1246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-015-2529-1

- Shirom A, Nirel N, Vinokur AD. Overload, autonomy, and burnout as predictors of physicians’ quality of care. J Occup Health Psychol. 2006;11(4):328-342. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.11.4.328

- Hayashino Y, Utsugi-Ozaki M, Feldman MD, Fukuhara S. Hope modified the association between distress and incidence of self-perceived medical errors among practicing physicians: prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35585. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035585

- Wen J, Cheng Y, Hu X, Yuan P, Hao T, Shi Y. Workload, burnout, and medical mistakes among physicians in China: A cross-sectional study. Biosci Trends. 2016;10(1):27-33. https://doi.org/10.5582/bst.2015.01175

- Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among U.S. medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(5):334-341. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-451. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134

- Dewa CS, Jacobs P, Thanh NX, Loong D. An estimate of the cost of burnout on early retirement and reduction in clinical hours of practicing physicians in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):254. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-254

- Soler JK, Yaman H, Esteva M, et al; European General Practice Research Network Burnout Study Group. Burnout in European family doctors: the EGPRN study. Fam Pract. 2008;25(4):245-265. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmn038

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023

- Oaklander M. Doctors on Life Support. Times Health. August 27, 2015 http://time.com/4012840/doctors-on-life-support/. Accessed July 20, 2018.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Summary of Changes to ACGME Common Program Requirements Section VI. http://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Common-Program-Requirements/Summary-of-Proposed-Changes-to-ACGME-Common-Program-Requirements-Section-VI. Accessed July 20, 2018.

- McManus IC, Keeling A, Paice E. Stress, burnout and doctors’ attitudes to work are determined by personality and learning style: a twelve year longitudinal study of UK medical graduates. BMC Med. 2004;2(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-2-29

- Maslach C, Leiter MP. Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93(3):498-512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.498

- Maslach C. Maslach Burnout Inventory (Abbreviated)–MBI-9. From: http://wisdom.web.unc.edu/files/2015/11/Burnout-Abbreviated-General.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2018.

- Maslach C, Jackson SF, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

- Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199

- Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Hoogduin K, Schaap C, Kladler A. on the clinical validity of the maslach burnout inventory and the burnout measure. Psychol Health. 2001;16(5):565-582. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440108405527

- Creswell JW. Mapping the developing landscape of mixed methods research. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, eds. Sage handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2010:45-68. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506335193.n2

- Borkan J. Immersion/crystallization. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, eds. Doing qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999:179-194.

- Ofei-Dodoo S, Kellerman R, Nilsen K, Nutting R, Lewis D. Family Physicians’ Perceptions of Electronic Cigarettes in Tobacco Use Counseling. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(4):448-459. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2017.04.170084

- National Academy of Medicine. Action Collaborative on Clinical Well-Being and Resilience. https://nam.edu/initiatives/clinician-resilience-and-well-being/. Accessed February 27, 2019.

There are no comments for this article.