Background and Objectives: Family medicine rural training track (RTT) residency programs produce a higher proportion of graduates who choose rural practice than other programs, yet RTTs face continuing threats to their existence. This study sought to understand threats to RTT sustainability and resilience factors that enable RTTs to thrive.

Methods: In 2014 and 2015, the authors conducted semistructured interviews of 21 RTT leaders representing two closed programs and 22 functioning programs. Interview topics included program strengths providing resilience and sustainability, risk factors for closure or vulnerabilities threatening sustainability, and advice for other RTTs. The authors performed a content analysis, coding pertinent themes in all interview data.

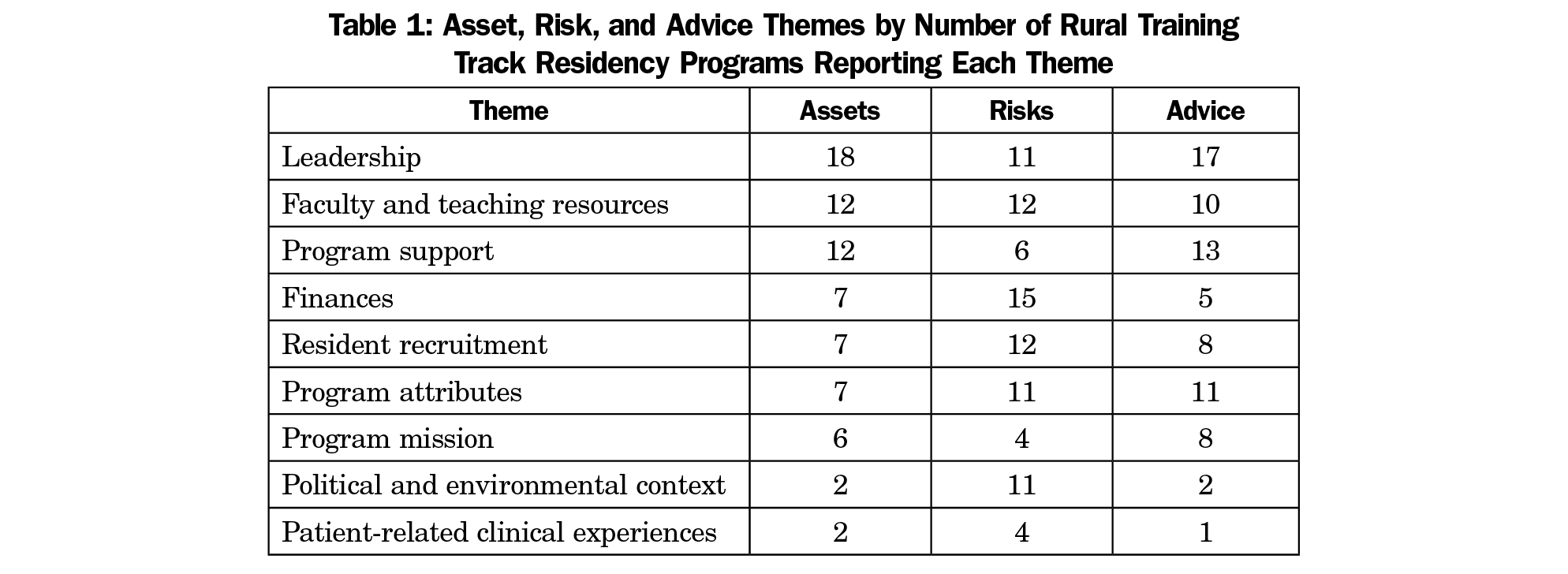

Results: From the top three assets, risks, and advice that respondents offered, the following nine themes emerged, in order from most to least mentioned: leadership, faculty and teaching resources, program support, finances, resident recruitment, program attributes, program mission, political and environmental context, and patient-related clinical experiences. Interviewees frequently reported multifactorial causes for RTT sustainability or closure.

Conclusions: Numerous factors identified, such as distance, can operate as positive or negative influences for program resilience, depending on place and context. Resilience depends on multiple forms of social capital, including robust networks among individuals and various communities: the local population and patients, local health care providers, residency faculty, and RTTs in general. The small size and remoteness of RTTs make them vulnerable to multiple challenges in finances, regulations, and accreditation, requiring program adaptability and suggesting the need for flexibility in the policies that govern them.

Integrated rural training track (RTT) residency programs in family medicine seek to address rural provider shortages by increasing the number and competence of physicians entering rural practice.1,2 Because of their small size, RTTs are substantially integrated with larger, usually more urban, programs and are separately accredited.3 RTT residents complete more than half their training in a rural location. RTTs take many forms, but the dominant model is 1 year of urban training followed by 2 years of rural training. Graduates choose rural practice at a rate two to three times that of family physicians overall.4,5 From 2000 to 2010, the number of RTTs declined from 35 to 25,5 but increasing interest in rural training, technical assistance efforts, and a growing supportive national community of RTT programs have led to a rebound to a total of 37 known operating programs in 2014.6 Given that one RTT graduates an average of two residents per year,7 the total number of RTT graduates annually has historically been fewer than 100.

Family medicine residency programs, especially rural programs, face significant threats to their existence. Despite encouraging trends since 2010, several programs have closed. A study of 27 family medicine residencies closing from 2000 to 2004 identified multiple closure warning signs, including financial factors, political and leadership challenges, and difficulty recruiting residents.8 Since then, changes in the organization of health care delivery and graduate medical education (GME) funding have presented new challenges. Because physician education in rural places is scarce relative to rural physician need, and RTTs remain vulnerable as the smallest residency programs, understanding if previously identified closure factors continue to have relevance, and if new or unique risks affect RTTs, is crucial. Understanding how RTTs can face challenges and become resilient is also critical for their survival. This study aimed to identify risk factors threatening RTT sustainability and resilience factors enabling existing and developing RTTs to avoid closure and thrive.

At a 2014 meeting of rural medical educators, three study team members led a discussion to identify important factors associated with RTT program success or failure. The findings, and the interview guide from the prior closure study,8 informed the development of this study’s interview questions. In 2014 and 2015 we contacted leaders of 28 functioning or recently closed RTTs to request a telephone interview. Twenty-four programs participated (85.7%). We first interviewed two leaders of programs closing in 2011 and 2012 to understand the dynamics, timing, and relative importance of closure factors, as well as suggestions for promoting RTT resilience. We then interviewed program directors, rural site directors, or both about program risks and resilience at 22 functioning programs. We defined resilience as “the capacity to endure and overcome hardship”9 and asked respondents to describe: (1) program strengths or assets providing resilience and sustainability, (2) risk factors for closure or vulnerabilities threatening sustainability, and (3) advice for other RTTs. We also asked respondents to identify their top three assets and risks. Two or three study team members conducted each telephone interview of 1 to 1.5 hours, recording responses by hand, and compiling and reconciling notes afterward.

We performed a thematic content analysis of interview data from all 24 programs using Atlas.ti version 8.0. We focused on the top three assets and risks identified as well as advice for other programs, identifying emergent themes and developing a coding scheme to classify risks and resilience factors. We applied the coding scheme to a subset of the interviews and then to all interviews, revising and applying codes iteratively until the two lead investigators reached coding consensus. The University of Washington Human Subjects Division reviewed and approved this study.

The 21 respondents participating in the study represented 24 programs (some respondents operated more than one residency program). Six were residency program directors for both urban and rural sites, nine were rural site or associate program directors, and six were both program director and rural site director. Programs had existed from less than 1 to 31 years (median 15 years), beginning in the 1980s (1), 1990s (10), 2000s (4), or 2010s (9). We present results according to nine key themes (Table 1), summarizing risk and resilience factors as well as advice offered, if applicable, within each theme. Frequency of occurrence, where noted, refers to numbers of respondents mentioning the theme, not utterances. Illustrative interviewee comments are reported in Tables 2 through 5 by theme.

Leadership

Effective leadership (Table 2) in the sponsoring institution and residency program was the most commonly cited asset and subject of advice, and the second most common risk cited. Effective program leaders were passionate, dedicated, and respected in the community; had a solid understanding of program finances; engaged in strategic planning anticipating program needs, including succession planning; promoted program value; built relationships with community members, sponsoring institutions, and a peer network for support; and engaged in creative problem-solving, including seeking technical assistance.

A change in leadership in the hospital, sponsoring institution, or program could critically affect program success. Program or rural site director burnout was a particular risk when support staff or teaching resources were insufficient to share the load. Difficulty recruiting program leaders to ensure continuity was a commonly cited risk, the most crucial factor identified in one program’s closure. Other risks included frequent leadership turnover or an unsupportive leader in any organization relied on for sponsorship or operations.

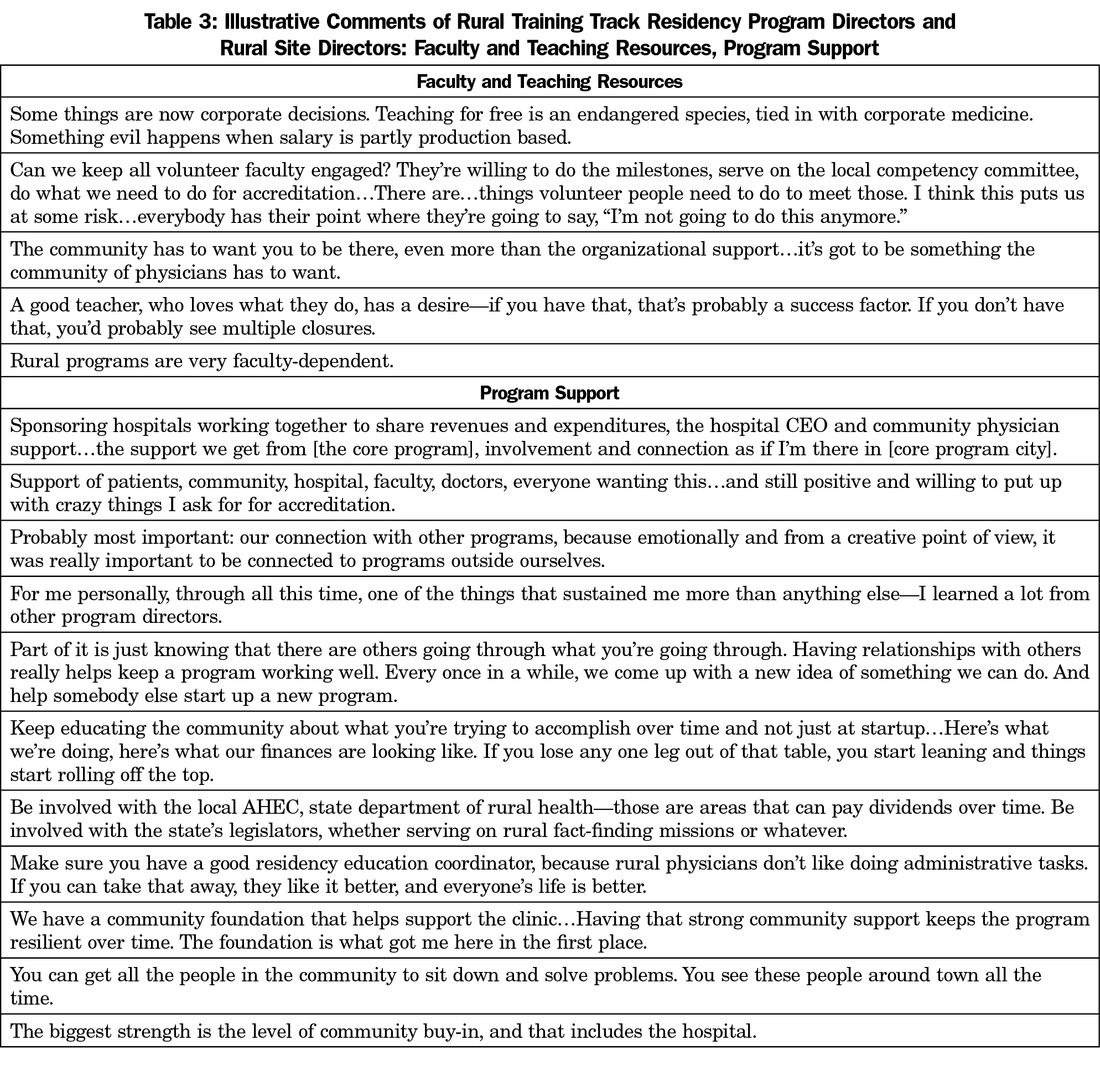

Faculty and Teaching Resources

Paid and volunteer faculty, the most valued RTT teaching resource, was the second most commonly cited asset (Table 3). Faculty dedication was often described in terms of community relationships: faculty longevity and embeddedness in the local community and the faculty as a community of skilled, experienced clinicians offering residents a broad scope of training. Program leaders emphasized the importance of recruiting faculty who were a good fit for the program and community. An RTT’s existence in a community, often taken as evidence of a high-quality practice environment, could be used as a tool to attract physicians interested in teaching opportunities.

Challenges involving faculty and teaching resources were the second most frequently cited risk. Rural communities already struggling to recruit providers similarly find recruiting and retaining faculty difficult. Some programs reported lack of support for faculty to teach due to productivity pressures. Faculty burnout could be both cause and consequence of faculty shortages, exacerbated in communities too small to support enough providers that consequently lack enough clinical training opportunities. These challenges threatened the quality of the resident teaching experience with the potential to discourage the recruitment of both new faculty and residents. Other risks included insufficient support for faculty development and protected teaching time, as well as narrowing scopes of practice, due paradoxically to competition for patients from other providers and subspecialists.

Program Support

Interviewees cited multiple, varied examples of support for RTTs (Table 3). The “community”—medical community, host community, patients, other RTTs, or a general, unspecified notion of community—was the most frequent way interviewees described support systems. Human resource support, such as administrative support provided by the core residency education coordinator or site residency coordinator, was also frequently mentioned. Other sources of support included hospital and clinic staff, patient support of resident training, and other entities such as Area Health Education Centers (AHECs) or the local health department. Peer support through interaction with other RTT program personnel and consultant technical assistance were particularly valued.

Lack of support from any of these actors—education or program coordinators, the local community, the medical community, the hospital, peers—or lack of a local champion external to the program were risks clustered under this theme.

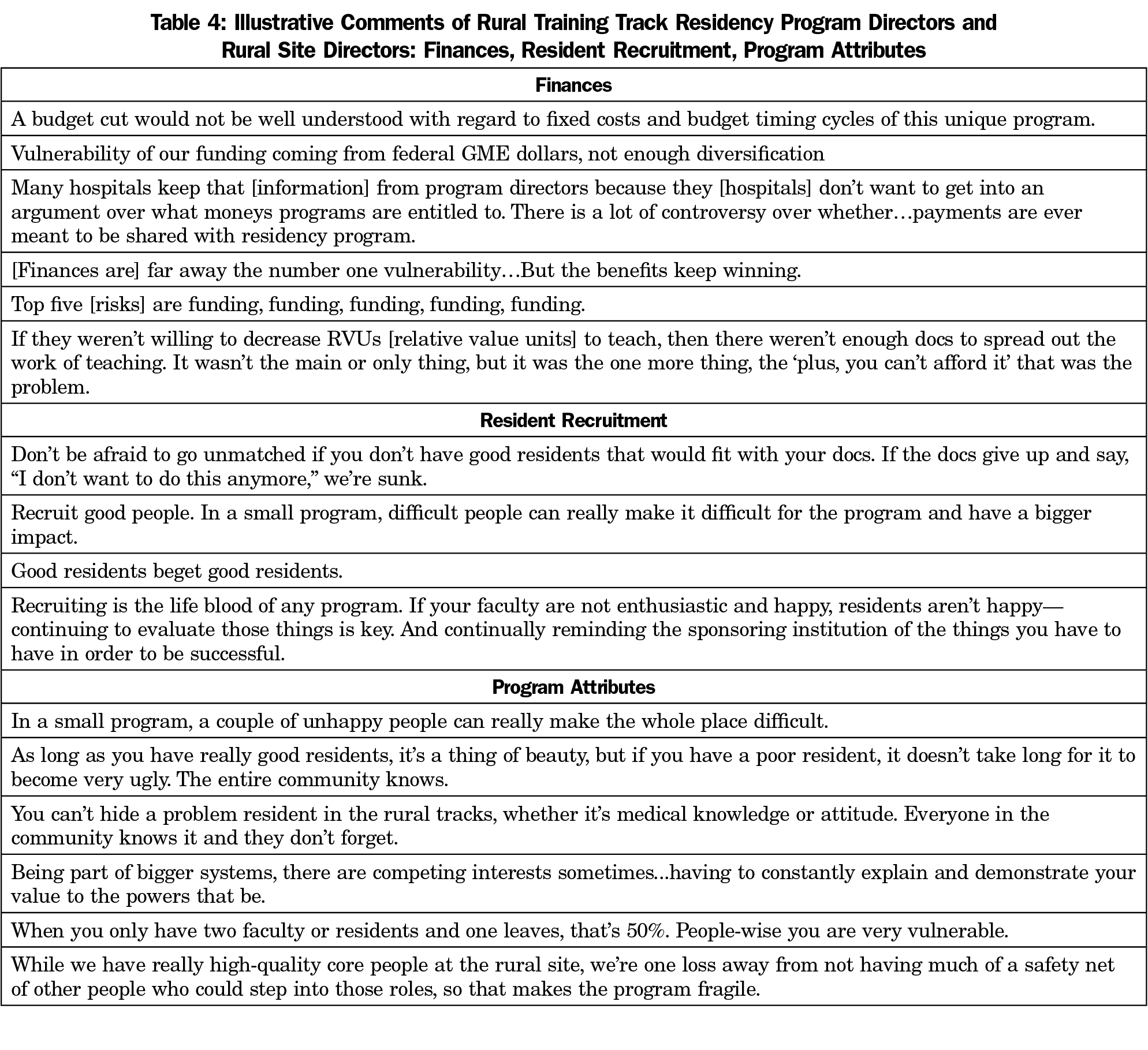

Finances

Managing financial risks is a key preoccupation of RTT leaders (Table 4). Multiple RTTs reported reliance on grants for program planning and implementation. RTTs reporting the strongest finances cited good partnerships with sponsoring programs, other stable funding sources, or diverse funding sources such that programs were not overly dependent on any single source. RTTs in predominantly rural states may enjoy greater state government awareness and financial support. For example, in one mostly rural state, resident slots were state funded. Financial sponsorship also carried symbolic value, as one interviewee cited the combination of the hospital’s “moral support with financial support” as a key asset.

Most programs cited real or potential financial risks. Limited RTT funding generally or lack of sustained funding after startup grants were frequently cited risks. A sponsoring institution’s lack of transparency with RTT leadership could complicate budgeting and indicate unwillingness to share responsibility for financial decisions and outcomes. Small changes in a sponsor’s much larger budget or in the funding arrangement could have outsized negative impacts on RTTs. RTT patient populations are frequently poorer, resulting in a payor mix that generates low revenues. Even in the favorable environment of a rural state where the need for RTTs is well understood, there are risks: the RTT’s existence and contributions to rural workforce supply can be taken for granted. Dependence on either a predominant funding source or diverse funding sources could be a vulnerability if perceived responsibility for financial support is diffuse, the impact of funding arrangements is not transparent to sponsors, or those who hold the purse strings do not perceive clear stakes in the RTT’s success.

Resident Recruitment

Residents, like faculty, are critical program assets (Table 4). Apart from being the reason for a program’s existence, high-quality residents improve practice and learning environments and ensure future recruitment and socialization of good residents, perpetuating program success. Recruitment assets included solid learning opportunities, particularly a small program’s ability to provide individual attention, strategic recruitment relationships, and mission-aligned and mission-driven residents.

Tied with faculty, difficulty recruiting residents was the most frequently cited risk to program viability. Recruitment difficulties included inability to fill resident positions, residents (or significant others) who were poor matches for the program or community, and finding the proper balance in the number of residents a program could support. Fewer residents allowed for more individual attention, with the risk that poor outcomes could not be spread across a larger pool to mitigate overall program impact.

Program Attributes

Numerous program attributes were cited as influential (Table 4). By definition, RTTs are small and rural. Small size was an identified asset allowing some programs to be more manageable, nimble, and flexible to adapt to resident needs or changing circumstances. The appeal of rural living and amenities were positive recruitment assets for some programs. Other attributes that were cited as assets included newer, high-quality equipment or facilities; optimal distance to sponsoring programs or urban areas; relative independence in being less visible to the larger program; and the fact that the RTT’s function and priority is to serve community needs for patient care and for provider recruitment.

Interviewees more often cited small program attributes as risks than as assets. Being small frequently meant too small, isolated, or undervalued. Small programs functioned at a power disadvantage in relation to urban sponsors, vulnerable to being overlooked or eliminated through budget cutting or reallocation or being swallowed up by larger systems. Small programs can struggle to provide enough geriatric, pediatric, or other patients to meet clinical experience requirements for accreditation. Small programs are more vulnerable to the impacts of a single bad apple or poor relationship dynamics. Outdated equipment or facilities can discourage resident and faculty recruitment. The appeal of rural or remote living is not universal, and some communities have fewer amenities to attract residents and faculty. A community can be too isolated, or conversely, grow to become too urbanized.

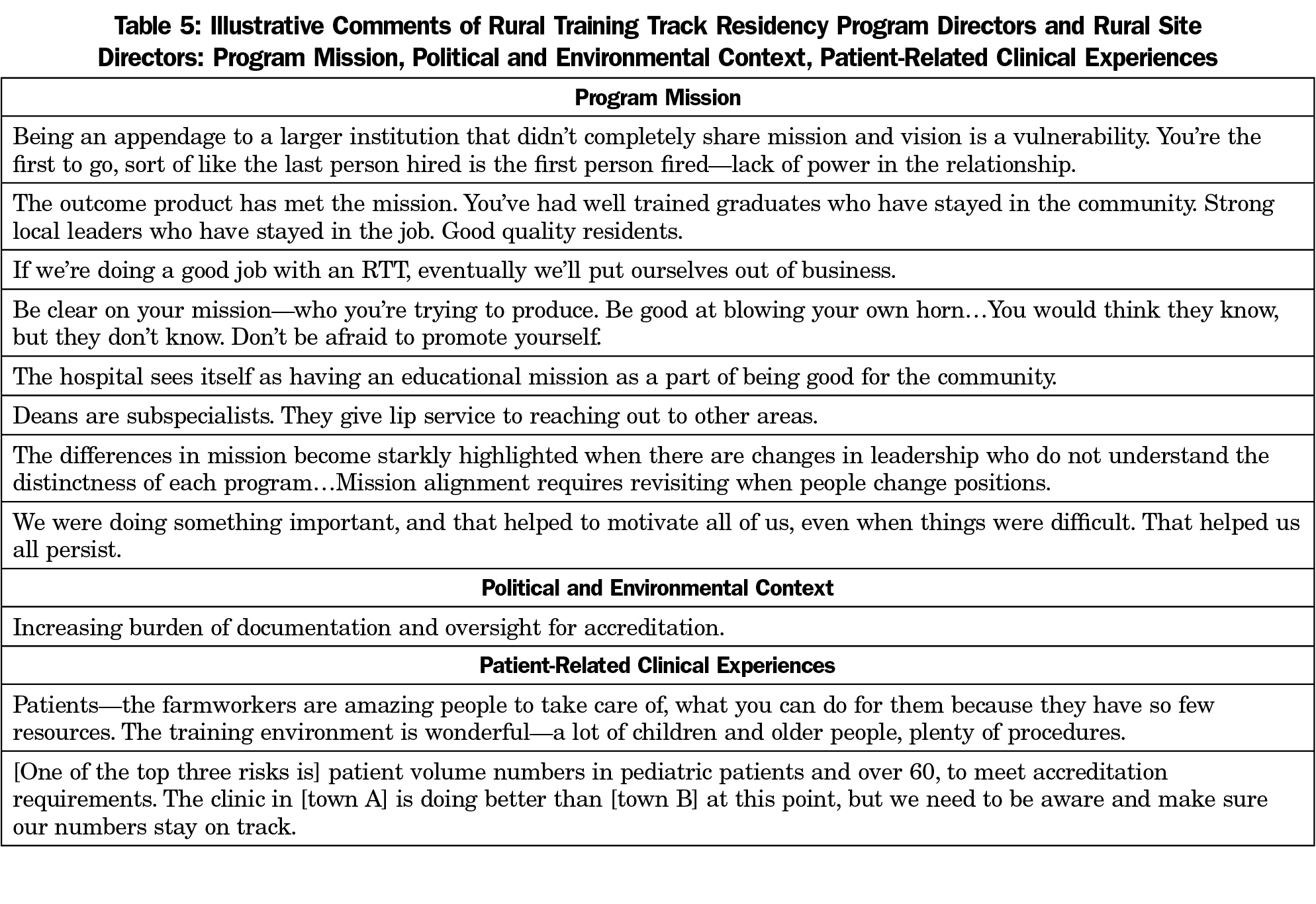

Program Mission

Alignment of missions between RTTs and sponsoring programs was considered important for long-term sustainability (Table 5). A track record of success in meeting the mission to provide rural physicians for local communities was itself considered an asset in continuing to attract resources to the RTT.

Lack of mission specificity or alignment, and especially lack of clear commitment from the sponsoring program to training physicians for rural practice—through its articulated mission and actions—were seen as risks. Rather than citing mission as an asset or risk, interviewees more often offered advice about program mission, stressing the importance of finding ways to align RTT missions with the missions of sponsoring programs and other organizational partners.

Political and Environmental Context

Notably few interviewees cited political or environmental assets that boded well for continued RTT success (Table 5). These assets included state government recognition of the RTT program’s value, including financial support and legislator backing, as well as increased medical student and resident interest in rural medicine.

Much more often, interviewees viewed the political, environmental, and regulatory context within which RTTs operated as threatening. Even some highly successful programs reported concerns about the future, including health system changes that could affect residency training (eg, mergers), changes in financial stability (eg, a loss of state support), fear of competition to recruit great residents, or a shifting balance of power between the sponsoring program and RTT.

Overwhelmingly, the most common contextual risk cited concerned challenges with Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requirements. These included fulfilling ACGME Milestones, the increasing burden of documentation for accreditation, scholarly activity requirements that are not financially supported, and the unification of allopathic and osteopathic residencies under a single ACGME accreditation system.

Patient-Related Clinical Experiences

A complement to excellent faculty was the availability of good learning opportunities through patient clinical experiences (Table 5), including serving patients in the community and providing care for chronically underserved populations such as patients insured through Medicaid. A risk that several RTTs mentioned was an insufficient number of patients generally or particular types of patients, such as pediatric or geriatric patients, to provide adequate training.

A Holistic View of Risk and Resilience Factors

Some program leaders struggled to identify individual factors that were particularly consequential as risks or as resilience factors. Notably, interviewees from programs that had closed described closure as “multifactorial” and “a perfect storm,” including financial issues, a resident failure on boards (the impact of small numbers where one failure is magnified), an unsupportive sponsoring institution, difficulty recruiting faculty, and inability to identify a successor for a retiring program director. Thus, although a critical precipitating event or circumstance may have preceded closure, it was the confluence of multiple risks without sufficient assets to offset those risks that ultimately caused closures.

This study has limitations. The usual limitations of qualitative inquiry apply here, and our results reflect the viewpoints of program leadership. As we have shown, RTT success or failure is multifaceted, and we may have missed information from other actors that could provide greater insight into our study questions. Because RTTs are a small proportion of all family medicine residencies, the size of the study population prevented us from determining with certainty all necessary and sufficient factors for resilience and success, and which factors, alone or in combination with others, are necessary and sufficient to cause closure. The 10 separately-identified themes at times overlapped and thus were not always neatly classifiable as discreet concepts. Despite these limitations, a qualitative investigation is especially appropriate for illuminating complex relationship dynamics and key historical processes that help account for RTT program success or failure.

To some degree, the themes described by this study’s key informants—human resources, finances, mission, etc—are likely no different than the determinants of success for all residency programs. The context of rural and lower resource environments, however, poses unique challenges for RTTs, with less margin for error, and the consequences of failure may be more keenly felt in small communities than in urban environments.

Multiple domains of influence could operate distinctly in different places. For example, opinions varied on the optimal distance between the rural site and the sponsoring residency program. How rural should a rural training track be? Being too close to the urban site can deprive residents of a truly rural experience throughout the 3 years of residency; being too far away can mean that rurally-motivated students are discouraged by having to spend the first year in an environment they consider too urban. Depending on region of the country, some interviewees considered either 45 minutes’ or 2 hours’ driving distance optimal, demonstrating the role that context plays in determining whether a factor constitutes a program asset or a vulnerability.

It is worth noting that closed programs reported having extremely dedicated site directors, hospital administrators, local health providers and faculty, as well as community support. Despite all these advantages, the loss of key assets, such as sponsor support through financial backing or program leadership that could not be replaced, was enough to cause a program to close. No residency program, large or small, can long endure financial or leadership deficits, but small and remote programs are particularly vulnerable to circumstances that may be beyond their control. Tracking residency closures and examining the causes in depth is an important area of further research.

The concept of community was used to describe many different types of groups: the local population and patients, local health care providers, residency faculty, and RTTs in general. The ubiquity of references to community and the importance of the support of these multiple communities reinforce the notion that resilience is a property not only of individuals but of networked communities.9 RTTs appear to be critically dependent on cultivating multiple forms of social capital for their success.

Despite the frequently cited role of community embeddedness for sustainability, environmental changes have required some programs to move to a new community offering more favorable conditions. This phenomenon raises questions about which communities of support are truly essential. The ability of a residency program to reinvent itself in a new location shows that above all, RTTs must be adaptable, and that there is no single factor that can guarantee resilience and success.

All RTT leaders were able to identify vulnerabilities, even though several sites did not appear to be suffering from specific vulnerabilities at the time of the interview. No doubt losing any of these programs, when there are so few and when communities depend on them for health care workforce development, would represent a significant loss both to affected communities and to the larger enterprise of rural training and recruiting to rural practice. It is clear that financial, regulatory, and accreditation challenges loom large for RTTs. It is likely that osteopathic programs, which are also frequently rural and smaller in size and will soon be subject to the same standards as allopathic programs, may face similar challenges that threaten their survival. Further research should examine how rural and small osteopathic programs fare during and after the transition.

Targeted technical assistance, particularly in the areas of finance, governance, faculty and leadership succession, and accreditation, will be key to addressing RTT vulnerabilities.5,6 Networking with peers around the United States to identify resources and share lessons learned can foster a community of practice that encourages performance improvement.5,7 RTTs could benefit greatly from transparency in GME finance and more direct funding of programs that operate primarily in outpatient settings to increase accountability and provide more local control.6 Collaboration among local and state stakeholders with an interest in rural workforce development, such as state offices of rural health, AHECs, and rural safety net facilities (eg, critical access hospitals), can also help identify new opportunities to expand rural residency training.5,6 This study’s findings suggest that policies providing flexibility in residency program design, finance, and regulation, indeed any one or all of these, could improve the sustainability of small family medicine residency programs more broadly, including but not limited to RTTs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sherry Adkins, Letitia Reason, and Andrea Corage-Baden for their contributions to study development and data analysis.

Financial support: This study was supported by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under cooperative agreement #UA9RH26027. The information, conclusions and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and no endorsement by FORHP, HRSA, or HHS is intended or should be inferred.

Presentations: Portions of the material submitted here for publication were presented in the following venues:

Rural Health Summit; September 1, 2015; Portland, OR.

National Organization of State Offices of Rural Health Annual Meeting; October 29, 2014; Omaha, NE.

References

- Patterson DG, Longenecker R, Schmitz D, Skillman SM, Doescher MP. Policy brief: training physicians for rural practice: capitalizing on local expertise to strengthen rural primary care. Seattle, WA: WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, University of Washington; January 2011.

- Longenecker RL, Wendling A, Hollander-Rodriguez J, Bowling J, Schmitz D. Competence revisited in a rural context. Fam Med. 2018;50(1):28-36. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2018.712527

- Longenecker R. Rural medical education programs: a proposed nomenclature. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(3):283-286. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-16-00550.1

- Rosenthal TC. Outcomes of rural training tracks: a review. J Rural Health. 2000;16(3):213-216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2000.tb00459.x

- Patterson DG, Schmitz D, Longenecker R, Andrilla CHA. Family medicine rural training track residencies: 2008-2015 graduate outcomes. Seattle, WA: WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, University of Washington; February 2016.

- Patterson DG, Schmitz D, Longenecker R, Squire D, Skillman SM. Graduate medical education financing: sustaining medical education in rural places. Seattle, WA: WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, University of Washington; May 2015.

- Patterson DG, Longenecker R, Schmitz D, Phillips RL Jr, Skillman SM, Doescher MP. Rural residency training for family medicine physicians: graduate early-career outcomes, 2008-2012. Seattle, WA: WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, University of Washington; January 2013.

- Gonzalez EH, Phillips RL Jr, Pugno PA. A study of closure of family practice residency programs. Fam Med. 2003;35(10):706-710.

- Longenecker R, Zink T, Florence J. Teaching and learning resilience: building adaptive capacity for rural practice. A report and subsequent analysis of a workshop conducted at the Rural Medical Educators Conference, Savannah, Georgia, May 18, 2010. J Rural Health. 2012;28(2):122-127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00376.x

There are no comments for this article.