As family medicine (FM) programs offer more distributed training sites1-3 journal clubs (JCs) are going online, with the benefit of offering distributed learners the opportunity to share their experiences.4-18 Little is known about the learning experience of online JCs.19,20 eLearning appears to be as effective in increasing knowledge levels.21 Social media also enhances learner engagement and collaboration but may be hampered by technical and privacy issues.22 Based on the studies suggesting that learners prefer e-learning as a complement to face-to-face teaching, we designed a hybrid online-traditional JC23 and explored the learner experience.

BRIEF REPORTS

Family Medicine Journal Club: To Tweet or Not to Tweet?

Lina Al-Imari, MD, CCFP | Melissa Nutik, MD, MEd, CCFP | Linda Rozmovits, DPhil | Ruby Alvi, MD, CCFP | Risa Freeman, MD, CCFP, MEd

Fam Med. 2020;52(2):127-130.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2020.705062

Background and Objectives: Online journal clubs have recently become popular, but their effectiveness in promoting meaningful discussion of the evidence is unknown. We aimed to understand the learner experience of a hybrid online-traditional family medicine journal club.

Methods: We used a qualitative descriptive study to understand the experience of medical students and residents at the University of Toronto with the hybrid online-traditional family medicine journal club, including perceived useful and challenging aspects related to participant engagement and fostering discussion. The program, informed by the literature and needs assessment, comprised five sessions over a 6-month period. Learners led the discussion between the distributed sites via videoconferencing and Twitter. Six of 12 medical students and 33 of 57 residents participated in one of four focus groups. Thematic data analysis was performed using the constant comparison method.

Results: While participants could appreciate the potential of an online component to journal club to connect distributed learners, overall, they preferred the small group, face-to-face format that they felt produced richer and more meaningful discussion, higher levels of engagement, and a better learning opportunity. Videoconferencing and Twitter were seen as diminishing rather than enhancing their learning experience and they challenged the assumption that millennials would favor the use of social media for learning.

Conclusions: Our study demonstrates that for discussion-based teaching activities such as journal club, learners prefer a small-group, face-to-face format. Our findings have implications for the design of curricular programs for distributed medical learners.

Participants from five distributed sites at the University of Toronto, including three family medicine residency teaching units (FMTU) and two medical student campuses, were recruited via email and word of mouth. Ontario Telemedicine Network (OTN) videoconferencing and Twitter were employed to connect 12 medical students and 57 residents. During the duration of the program between September 2016 and May 2017, the average age of the class for the year 1 and 2 medical students was 23.6 years, and the average age for the residents from the three sites was 31.5 years (range: 26 to 47 years).

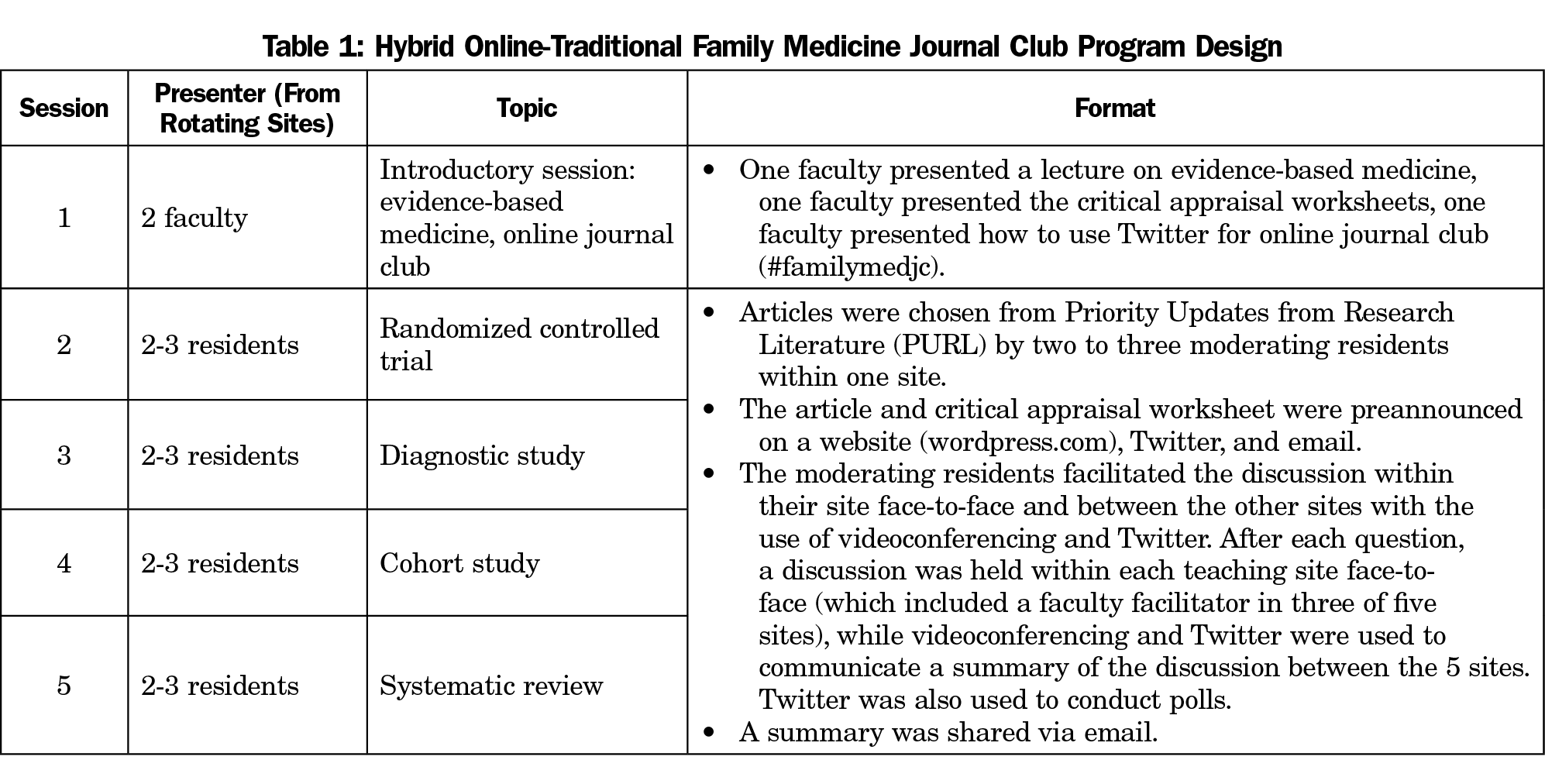

After an introduction, four JCs were held over a 6-month period (Table 1). Using a critical appraisal worksheet, groups of two to three residents from one of the FMTUs facilitated face-to-face discussions within their group and between the other sites using OTN and Twitter.

Focus groups were conducted by an experienced, independent qualitative researcher including one focus group for the residents at each FMTU (n=33) and one focus group for all medical students (n=6). Written consent was obtained from all participants. Discussions were audio recorded for verbatim transcription. Transcripts were checked for accuracy against sound files and coded for anticipated and emergent themes using the constant comparison method including searches for disconfirming evidence.24-26 The University of Toronto REB approved the study (#33325).

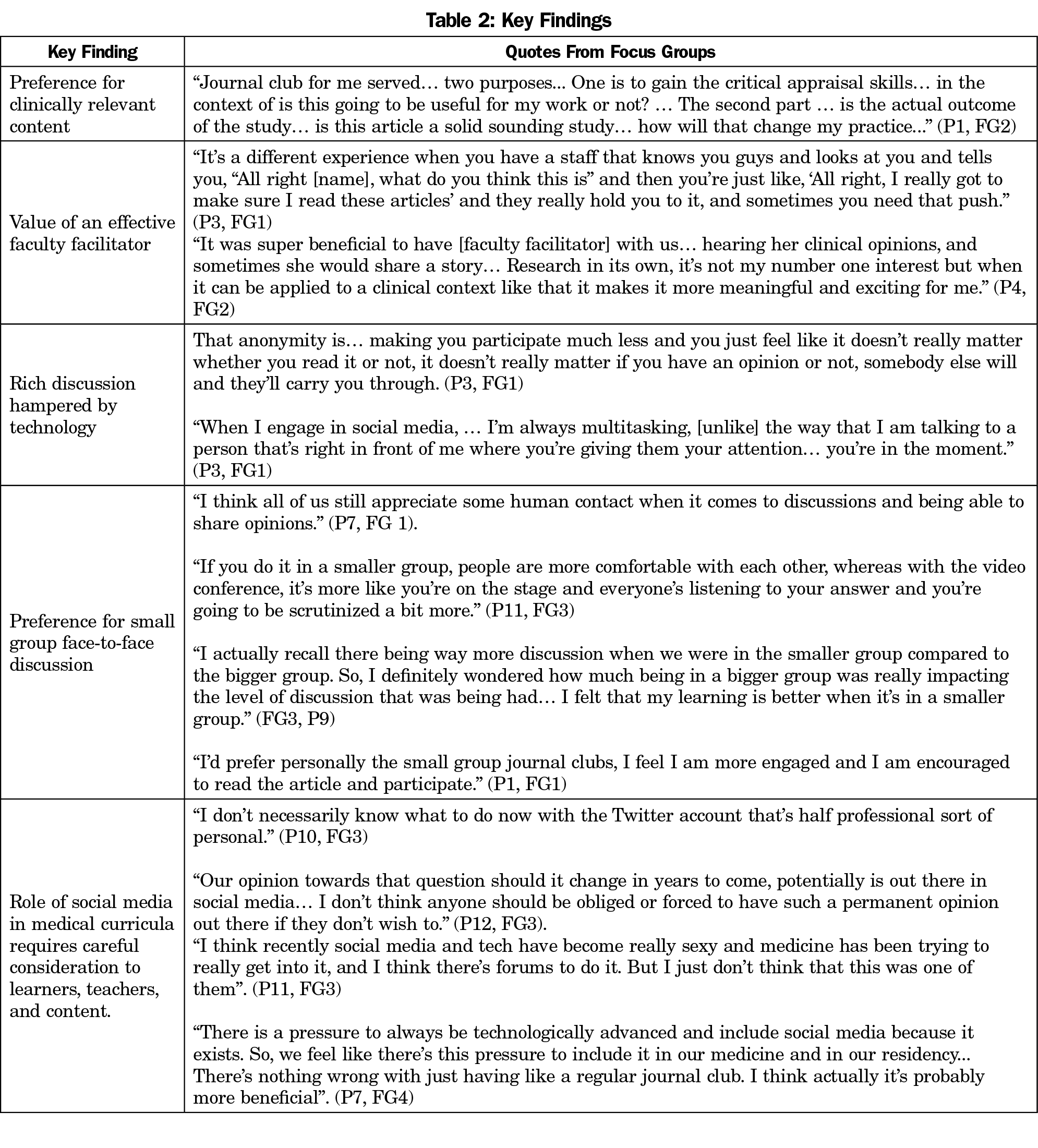

Participants valued four aspects of the program: content that is relevant to practice; an effective faculty facilitator; rich discussion; and a small-group, face-to-face environment (Table 2). Participants hoped JCs would enhance their critical appraisal skills, better equipping them to practice evidence-based medicine. Articles that were contemporary and relevant to FM were preferred for their clinical implications. Participants also highlighted the integral role that facilitators play in engaging and keeping the group on track. They especially valued the facilitators’ experience in contextualizing the research discussion in terms of patient care.

While technology was intended to enrich discussion by connecting our distributed learners, most participants felt that it had the opposite effect. Videoconferencing was found to be a cumbersome medium for discussion, often hampered by technical difficulties, and failed to produce dynamic experiences or meaningful connections. Similarly, although some participants felt Twitter had the potential to connect distributed learners, the majority found that it failed to engage learners because the anonymity diminished motivation to prepare for JC and participate in the discussion. Many also felt that the use of their phones and short character limit was not conducive to fostering the social connection that is integral to effective conversations.

Most strikingly, participants raised some interesting assertions related to the role of social media in medical curricula (Table 2). Some indicated that they never used Twitter, and those who did reserved it for personal use. Many were ambivalent about overlapping their personal lives with their professional roles and were also concerned about JC discussions taking place in a public, and potentially permanent sphere. While learners valued the opportunity to draw on the experiences of peers at other sites, a small-group, face-to-face JC format was most effective in promoting engagement and fruitful discussion.

Our study provides insight into the experience of distributed learners with technology in the context of a JC. While technology connected learners, combining videoconferencing and Twitter with a face-to-face session was not found to be conducive to rich discussion. Many participants felt that technology hampered discussion as it divided participants’ attention. Since active engagement in discussion is central to learning in JCs,27-30 participants indicated that the face-to-face format provided a superior learning experience. This finding is shared by another hybrid JC employed by geriatric subspeciality trainees10 and echoes a study by McLeod et al, who noted that participation among general surgery residents was lower in the internet-based group compared to the face-to-face sessions.13 As attention is a finite resource, the advantage of face-to-face JCs may be the opportunity to be fully present whereas electronically-mediated human interactions divide our attention.31

The large-group nature of the hybrid JC also decreased the motivation of learners to participate. Research shows that although large groups can be more efficient at disseminating information, they are inferior to small groups in stimulating thinking and, as seen in our JCs, in engaging in discussion.32,33

It is noteworthy that the public nature of social media did not foster a safe learning environment. A similar fear of committing opinions to print was noted in online JCs for general surgery trainees.11,14 A private online discussion forum may have provided a more comfortable environment for learners to share differing viewpoints. Currently, there is limited role modelling of professional online physician identities or how to establish boundaries between professional and personal electronic personas. This may have further contributed to learners’ discomfort.

While this was a small-scale study limited by our inability to collect the ages of all participants, our findings suggest that the incorporation of technology in medical curricula requires careful consideration in relation to the learners, the content, the educational milieu, and the teachers.34-36 Future research can assess our hybrid model in other disciplines and with other technologies that may be better suited to discussion-based learning activities amongst distributed learners.

Our findings suggest that learners value face-to-face, small-group sessions for JCs. Learners learn best in a safe environment, and achieving a meaningful connection matters in discussion-based learning activities.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: The Dr Harrison Waddington Fellowship provided funding through the Office of Education Scholarship, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto.

Presentations: This study was presented at Family Medicine Forum, November 14, 2018, in Toronto, Canada, and as a poster presentation at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference on April 28, 2019 in Toronto, Canada.

References

- Sandars J, Morrison C. What is the Net Generation? The challenge for future medical education. Med Teach. 2007;29(2-3):85-88. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590601176380

- Canadian Resident Matching Service. Program descriptions by discipline. Ottawa: CaRMS; 2018.

- Bates J, Frost H, Schrewe B, Jamieson J, Ellaway R. Distributed education and distance learning in postgraduate medical education. Members of the FMEC Postgraduate consortium; 2011.

- Roberts MJ, Perera M, Lawrentschuk N, Romanic D, Papa N, Bolton D. Globalization of continuing professional development by journal clubs via microblogging: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(4):e103. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4194

- Mehta N, Flickinger T. The times they are a-changin’: academia, social media and the JGIM Twitter Journal Club. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(10):1317-1318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2976-9

- Alguire PC. A review of journal clubs in postgraduate medical education. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(5):347-353. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00102.x

- Deenadayalan Y, Grimmer-Somers K, Prior M, Kumar S. How to run an effective journal club: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(5):898-911. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01050.x

- Sackett DL, Parkes J. Teaching critical appraisal: no quick fixes. CMAJ. 1998;158(2):203-204.

- Alper BS, Hand JA, Elliott SG, et al. How much effort is needed to keep up with the literature relevant for primary care? J Med Libr Assoc. 2004;92(4):429-437.

- Gardhouse AI, Budd L, Yang SYC, Wong CL. #GeriMedJC: the twitter complement to the traditional-format geriatric medicine journal club. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(6):1347-1351. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14920

- Hammond J, Whalen T. The electronic journal club: an asynchronous problem-based learning technique within work-hour constraints. Curr Surg. 2006;63(6):441-443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cursur.2006.07.003

- Ahn HH, Kim JE, Ko NY, Seo SH, Kim SN, Kye YC. Videoconferencing journal club for dermatology residency training: an attitude study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87(5):397-400. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-0285

- McLeod RS, MacRae HM, McKenzie ME, Victor JC, Brasel KJ; Evidence Based Reviews in Surgery Steering Committee. A moderated journal club is more effective than an Internet journal club in teaching critical appraisal skills: results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(6):769-776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.08.016

- Oliphant R, Blackhall V, Moug S, Finn P, Vella M, Renwick A. Early experience of a virtual journal club. Clin Teach. 2015;12(6):389-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12357

- Touchet BK, Coon KA, Walker A. Journal Club 2.0: using team-based learning and online collaboration to engage learners. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(6):442-443. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03340092

- Udani AD, Moyse D, Peery CA, Taekman JM. Twitter-augmented journal club: educational engagement and experience so far. A A Case Rep. 2016;6(8):253-256. https://doi.org/10.1213/XAA.0000000000000255

- Yang PR, Meals RA. How to establish an interactive eConference and eJournal Club. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(1):129-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.10.004

- Topf JM, Sparks MA, Phelan PJ, et al. The evolution of the journal club: from Osler to Twitter. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69(6):827-836. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.12.012

- Sterling M, Leung P, Wright D, Bishop TF. The use of social media in graduate medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):1043-1056. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001617

- Arnbjörnsson E. The use of social media in medical education: a literature review. Creat Educ. 2014;5(24):2057-2061. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2014.524229

- Wutoh R, Boren SA, Balas EA. eLearning: a review of Internet-based continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2004;24(1):20-30. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.1340240105

- Cheston CC, Flickinger TE, Chisolm MS. Social media use in medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88(6):893-901. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828ffc23

- Ruiz JG, Mintzer MJ, Leipzig RM. The impact of E-learning in medical education. Acad Med. 2006;81(3):207-212. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200603000-00002

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334-340. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:43.0.CO;2-G

- Corbin JM, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd ed. Sage Publications; 2007.

- Miles MB, Huberman M. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994.

- Wenger E. Communities of Practice. Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1999.

- Mattingly D. Proceedings of the conference on the postgraduate medical centre. Journal clubs. Postgrad Med J. 1966;42(484):120-122. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.42.484.120

- Price DW, Felix KG. Journal clubs and case conferences: from academic tradition to communities of practice. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28(3):123-130. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.180

- Quinn EM, Cantillon P, Redmond HP, Bennett D. Surgical journal club as a community of practice: a case study. J Surg Ed 2014;71(4):606-612.

- Crawford M. The world beyond your head: on becoming an individual in an age of distraction. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2016.

- Bligh D. What’s the point in discussion? Exeter, UK: Intellect Books; 2000.

- Edmunds S, Brown G. Effective small group learning: AMEE Guide No. 48. Med Teach. 2010;32(9):715-726. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.505454

- Ellaway R. Patterns of educational technology adoption and use. Med Teach. 2007;29(4):420-421. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701469479

- Ellaway RH, Topps M, Bahr T. Information and educational technology in postgraduate medical education. Members of the FMEC Postgraduate Consortium; 2011.

- Schwab JJ. The practical 3: translation into curriculum. Sch Rev. 1973;81(4):501-522. https://doi.org/10.1086/443100

Lead Author

Lina Al-Imari, MD, CCFP

Affiliations: Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Co-Authors

Melissa Nutik, MD, MEd, CCFP - Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Linda Rozmovits, DPhil

Ruby Alvi, MD, CCFP - Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Risa Freeman, MD, CCFP, MEd - Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Corresponding Author

Lina Al-Imari, MD, CCFP

Correspondence: 37 Green Ash Crescent, Richmond Hill, ON, L4B 3S1, Canada. 416-560-7594.

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.