Background and Objectives: Leadership positions in academic medicine lack racial and gender diversity. In 2016, the Council of Academic Family Medicine (CAFM) established a Leadership Development Task Force to specifically address the lack of diversity among leadership in academic family medicine, particularly for underrepresented minorities and women.

approach: The task force was formed in August 2016 with members from each of the CAFM organizations representing diversity of race, gender, and academic position. The group met from August 2016 to December 2017. The task force reviewed available leadership development programming, and through consensus identified common pathways toward key leadership positions in academic family medicine—department chairs, program directors, medical student education directors, and research directors.

consensus development: The task force developed a model that describes possible pathways to several leadership positions within academic family medicine. Additionally, we identified the intentional use of a multidimensional mentoring team as critically important for successfully navigating the path to leadership.

Conclusions: There are ample opportunities available for leadership development both within family medicine organizations and outside. That said, individuals may require assistance in identifying and accessing appropriate opportunities. The path to leadership is not linear and leaders will likely hold more than one position in each of the domains of family medicine. Development as a leader is greatly enhanced by forming a multidimensional team of mentors.

Diversity within medicine contributes to improved health outcomes as patients are more satisfied and have better health outcomes when cared for by providers with similar ethnic, racial, and language backgrounds.1-4 Unfortunately, today’s physician workforce does not mirror the general population.5 While the racial composition of medical students has slowly changed over time, diversity among family medicine residents, faculty, and leadership lags behind population trends.5,6 Women are also underrepresented in leadership positions. In 2017, only 17% of permanent department chairs across all specialties were women.7 Similar trends regarding racial and gender diversity exist throughout the various leadership positions of academic medicine.

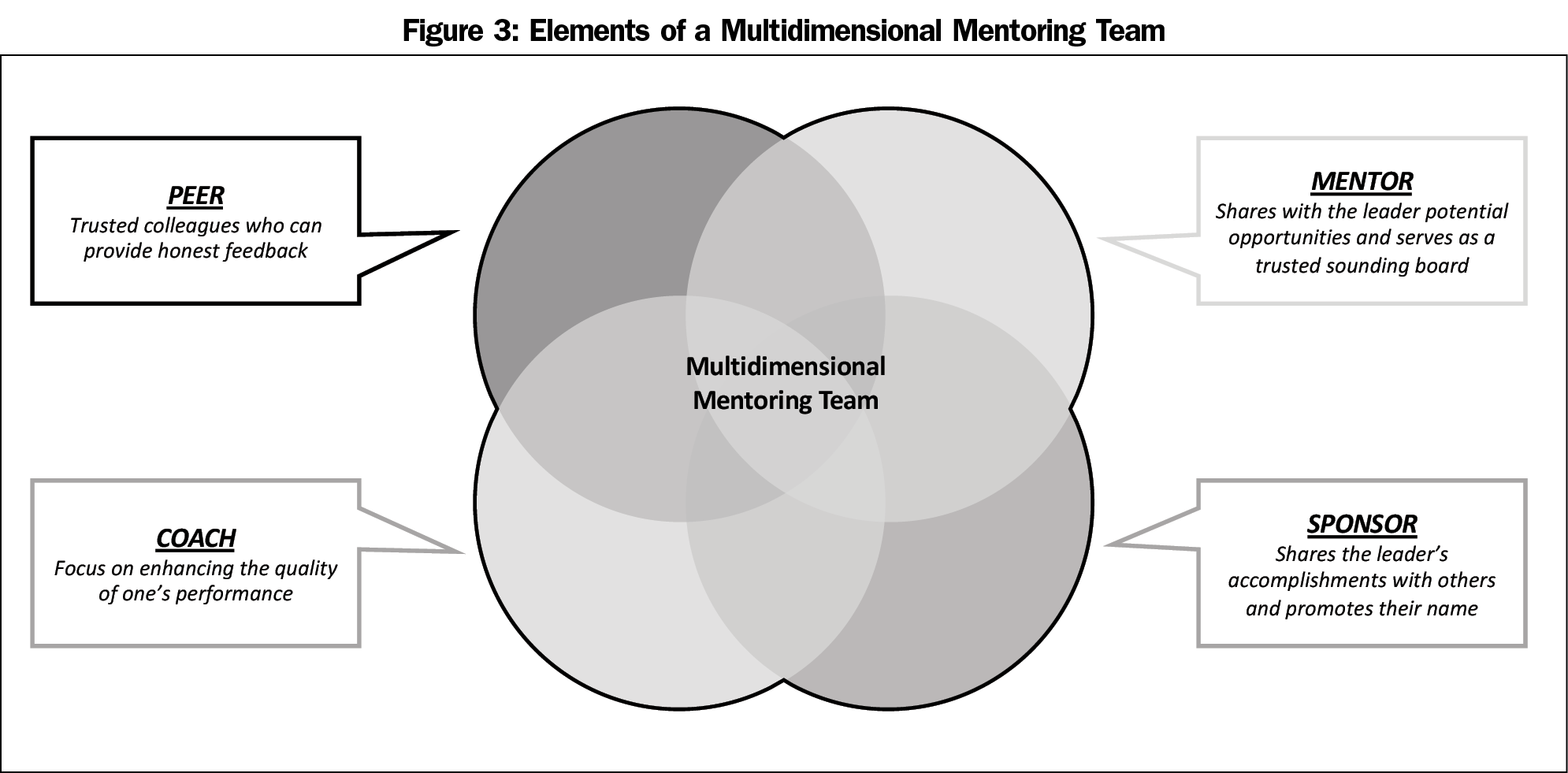

Several strategies have been proposed for advancing physicians into leadership roles, including mentorship, coaching, and sponsorship. Mentors traditionally work with their mentees to help them find resources and guide them toward their career goals.8,9 It is also important to note the need for multiple mentors as they provide different skill sets, experience, and opportunities for individuals to draw upon.8,10 Coaches focus on enhancing the quality of one’s performance, therefore faculty are more likely to succeed in each role they are given. Sponsorship is well described in the business world but has only recently been integrated into academic medicine.11 Sponsors help provide intentional visibility and vocal support for the potential leader and identify career advancement opportunities for women and minorities who may not have identified themselves as leaders.12,13

In 2016, the Council of Academic Family Medicine (CAFM) established a Leadership Development Task Force to specifically address the lack of diversity in academic family medicine leadership, particularly for women and underrepresented minorities (black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, American Indian/Alaskan Native). CAFM is comprised of the leadership of the four academic family medicine organizations: the Association of Departments of Family Medicine (ADFM), the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors (AFMRD), the North American Primary Care Research Group (NAPCRG), and the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM). Through its work, the task force sought to understand the pathways to leadership in academic family medicine and how those pathways differ based on ethnicity, gender, and other elements of diversity reflected by individuals within the pathways. The purpose of the task force was to identify trajectories for leadership for underrepresented minorities and women and to describe environmental influences that impact leadership acquisition.

The task force was formed in August 2016 and was comprised of key stakeholders from each of the CAFM organizations. The composition of this task force was intentionally convened with diversity in mind. Because the impetus for this effort came from ADFM (ADFM’s Leadership Development Committee) and STFM, CAFM agreed that authors J.S.P. and K.G. would serve as the leaders of this task force, representing ADFM and STFM, respectively. Joining them in the work were family medicine faculty representing a variety of ethnic and gender backgrounds, as well as different leadership roles and areas of expertise. An important constituency of the task force not included initially was that of emerging leaders in academic family medicine. Thus in February 2017, two individuals representing ADFM in the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Organization of Resident Representatives (C.L.C. and C.P.) joined the task force to provide this perspective.

Ultimately, the task force was comprised of eight members representing the academic spectrum including department chairs, deans, residency program directors, midcareer faculty, junior faculty, and trainees. The task force met quarterly via virtual calls and at semiannual meetings between August 2016 and December 2017. An executive staff member (A.D.) collated meeting minutes and distributed updated project information following the meetings to task force members.

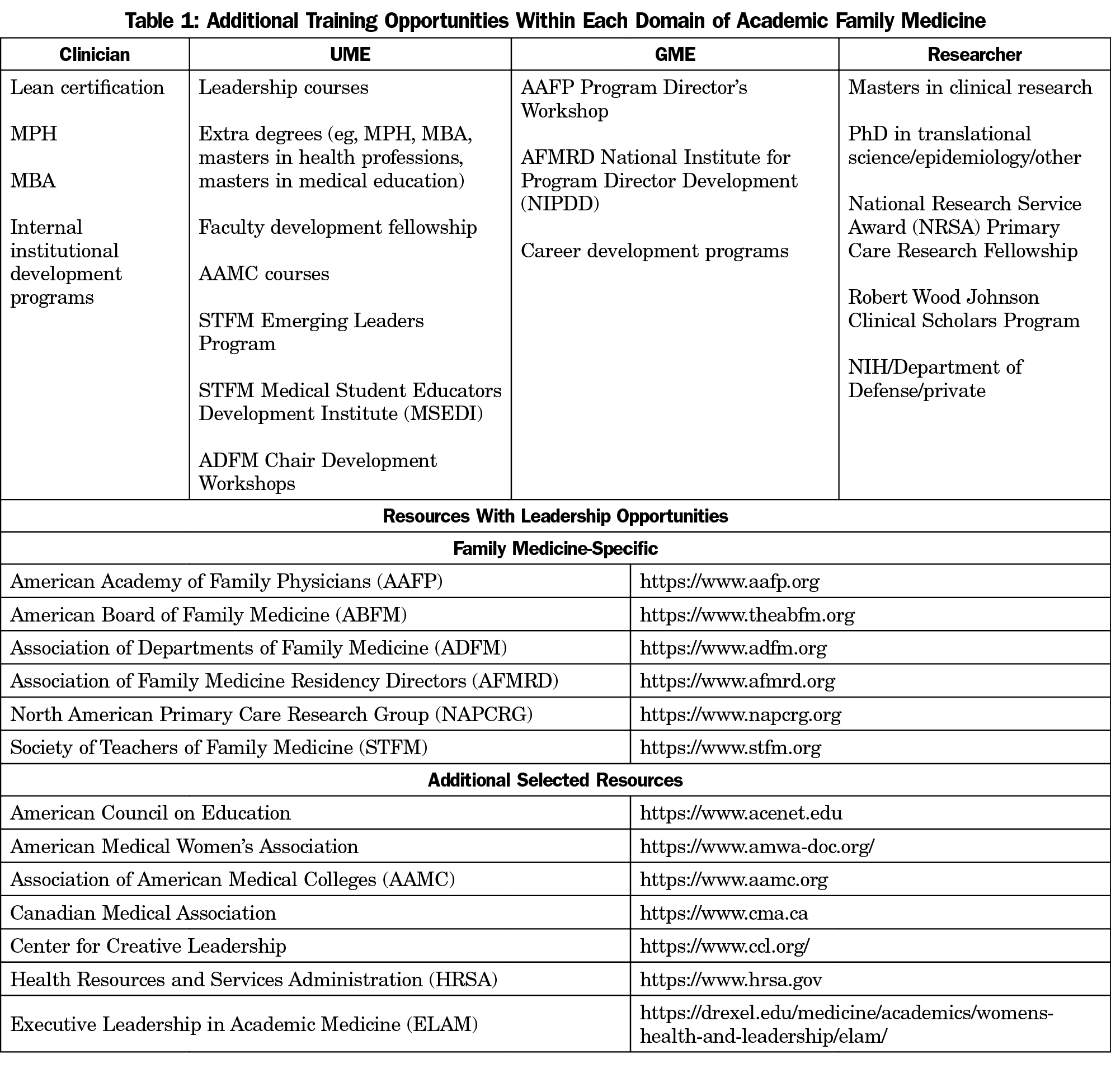

The task force compiled a list of leadership development programming available for faculty both internal and external to family medicine. The eight members of the task force independently reviewed opportunities on the STFM website for accuracy and availability. (https://www.stfm.org/facultydevelopment/otherfacultytraining/leadershipdevelopmentopportunities/overview/). Task force members searched other academic medical organizations, business, and higher education resources, recognizing that as faculty members progress further along in their careers (chairs, deans, etc), there are an increasing number of leadership development programs outside of family medicine organizations. A member of the task force (A.D.) compiled the collected data and sent it to task force members for additional comment and input before final synthesis.

Next, the task force defined and organized likely trajectories of leadership in academic family medicine and received feedback from CAFM leaders. To increase the diversity of stakeholder input, the task force presented the pathways at the 2017 and 2018 Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conferences. The workshops were led two to four members of the task force, and each session had more than 40 participants who contributed to the refinement of the pathways. A subsequent presentation of the model at the 2018 ADFM Winter Conference solicited the perspective of department chairs, who often select trainees and junior faculty for leadership positions and opportunities. It was through these additional discussions with stakeholders that the importance of mentorship, the various types of mentorship required, and the need to include mentorship into our pathways model were emphasized. Task force members integrated feedback from these stakeholders into the pathways model, resulting in the final, more comprehensive model of leadership development in academic family medicine.

The following results describe three major areas of review, and represent the consensus conclusions of the CAFM task force.

Domains of Academic Family Medicine

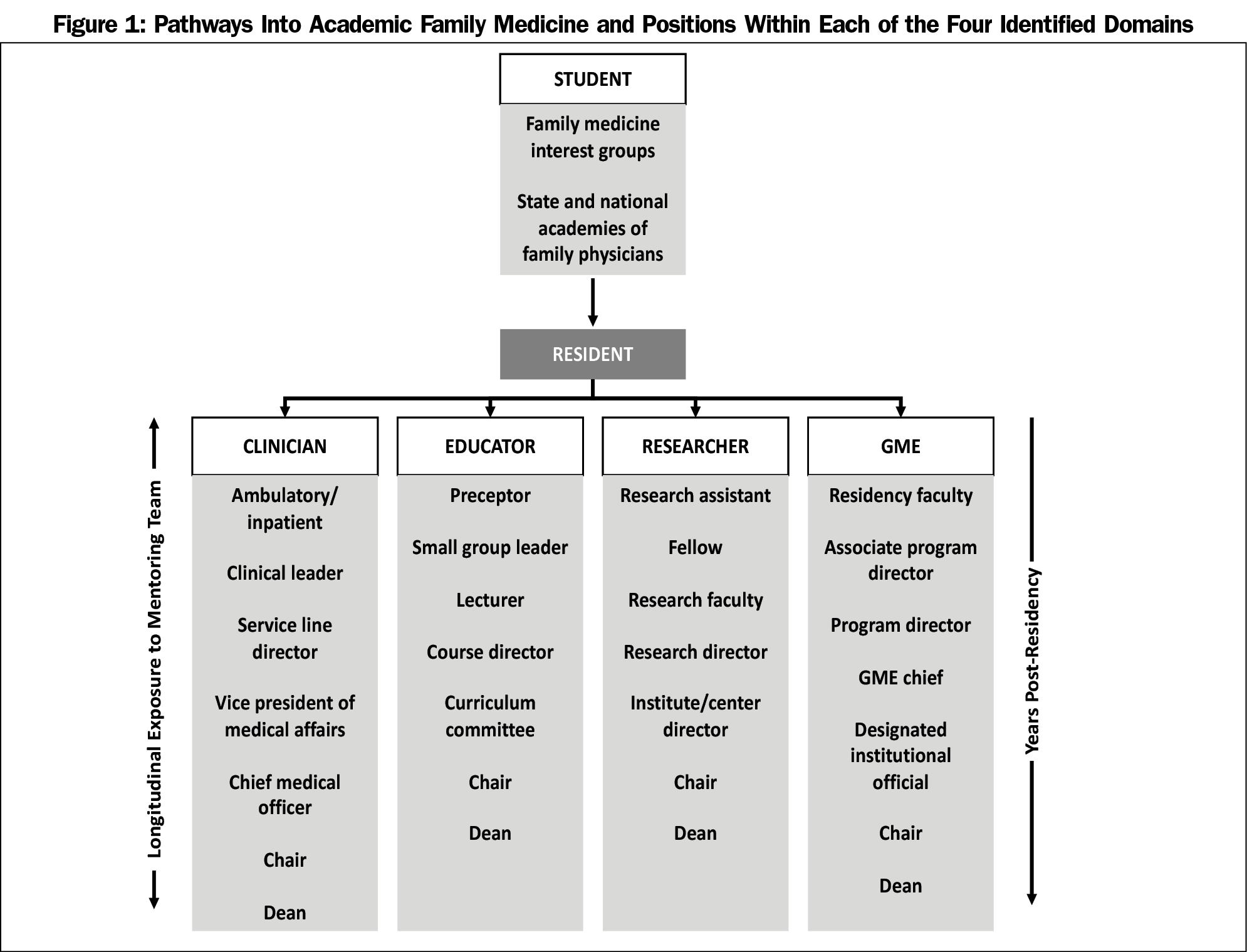

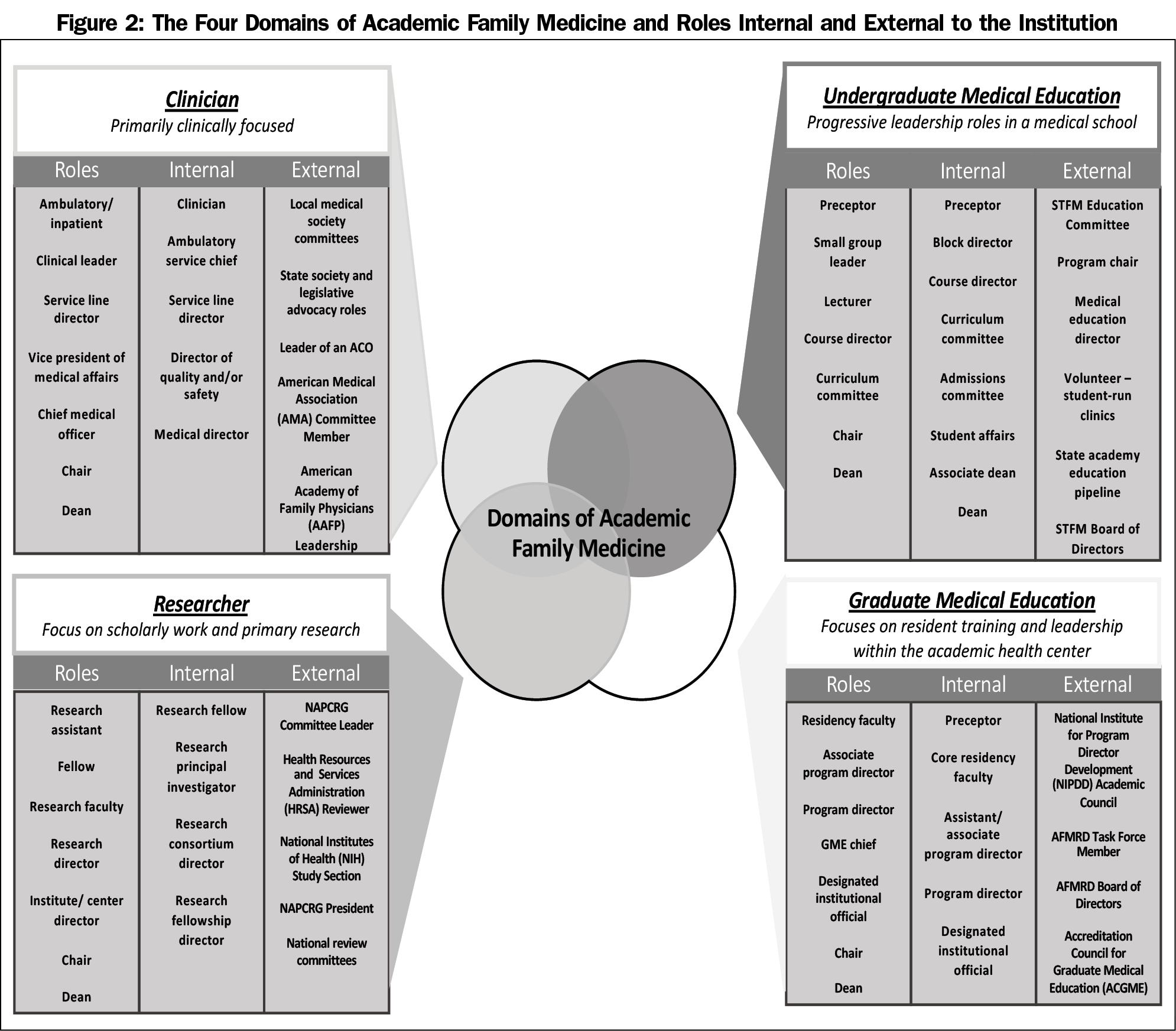

The CAFM task force evaluated pathways to key leadership positions within academic family medicine from the perspective of four representative constituent groups: department chairs (ADFM), program directors (AFMRD), medical student education directors (STFM), and research directors (NAPCRG). The task force identified four key domains within academic family medicine: clinician, researcher, undergraduate medical educator (UME), and graduate medical educator (GME). Through the assessment of these pathways, the task force generated an educational model (Figure 1) that contains possible pathways for several leadership positions. The model also identifies key entry points into the leadership pipeline through family medicine interest groups and state and local academies/chapters of family medicine. The model serves as an overall framework to think about leadership development. Figure 2 illustrates the four different domains identified as well as descriptions of roles and positions internal and external to the developing leader’s institution.

Leadership Development Opportunities

In review of available leadership development programming, the task force identified 26 leadership development programs available through family medicine organizations and 33 additional leadership development programs through outside organizations, such as the AAMC and specific academic institutions. Due to the transient nature of many of the leadership development programs and diverse offerings among various institutions, selected opportunities are listed in Table 1 and additional opportunities in the family medicine organizations on the career development area of the STFM website.14 Many of these opportunities require applications and often a cost for registration and travel. It is important to note that many institutions and programs offer internal and local opportunities that often do not have the barrier of cost or travel.

A critical outcome of the work of the task force was the acknowledgement that there are ample opportunities available for leadership development both within family medicine organizations and outside. However, a gap exists between program availability and the individuals who would benefit from them. We must find ways to direct developing leaders to the right opportunities at the right times in their career.

Multidimensional Mentoring Team

Simply being aware of the opportunities is not enough. A mentoring team is needed to help would-be leaders recognize and take advantage of the right opportunities. CAFM leaders acknowledged that in their pathway to leadership, a group of mentors rather than a single mentor guided them in various aspects of their professional development. This insight led to the conceptualization of a multidimensional mentoring team that might include those who can be described as coaches, mentoring peers, mentors, and sponsors (Figure 3). These roles are critical to preventing a mismatch between skills and opportunities which can lead to leaders feeling underutilized or overwhelmed. Figure 4 depicts the concept of how mentors provide a bridge to help disseminate opportunities and increase skills and preparations. In order to avoid underutilization or overwhelming of faculty members, mentors should orient them to institutional culture, share and draw analogies to personal experiences, and help align mentees with their individual vision/goals. Though all leaders benefit from a mentoring team, underrepresented minorities and women need a team that can also help them navigate some of the unique challenges they face in academic medicine.

Leadership development is not a linear process. Leaders will hold positions across the different domains throughout the path of professional development. Although listed in a hierarchical and linear fashion, it is important to note that the degree of leadership and weight of the position may vary among institutions, and therefore underscores the importance of a mentoring team to provide context and guidance for developing leaders.

This description of leadership development domains can help demystify potential pathways for aspiring leaders in their academic career. Mentors can also use this pathway model as a guide for discussion with their mentees. The multidimensional mentoring team comprised of people who can act in the role of a coach, sponsor, mentor, or peer mentor is an important resource to support the advancement of leaders.

We identified over 50 different leadership development training programs across the family medicine organizations and others in and outside of academia. Lack of a consistent platform promoting these programs, in addition to the requirement for an external nomination (rather than self-nomination) limits access to the most competitive programs which often propel faculty into top leadership positions. These programs also varied considerably in their cost, time commitment, and level of experience required to participate. Future program development should include not only descriptive content, but also exposure to corporate and academic culture, team building and communication, and negotiating strategies. It is critical to ensure that these opportunities are shared through proactive and intentional communication across CAFM organizations and their constituents.

Task force discussions highlighted the importance of family medicine interest groups and state and national academies of family physicians for inspiring future leaders. Institutional support for these opportunities and offering them at a low cost is key to facilitating student and resident entry into the leadership pipeline. Family medicine organizations should consider forming stronger partnerships with the Student National Medical Association, Latino Medical Student Association, and American Medical Women’s Association to build a pipeline of diverse leaders. These experiences provide students and residents exposure to organizational leadership and an introduction to different opportunities and possible mentors.

Challenges Faced by Minorities and Women

Many studies describe the lack of diversity in academia and higher attrition rates of minority faculty in general.15,16 Minority faculty are often in institutions with few professionals of color, which can lead to isolation and job dissatisfaction. A systematic review exploring the etiology of this found evidence that racism, promotion and funding disparities, lack of mentorship, and diversity pressures (both personal and institutional) exist and affect minority faculty.17 Underrepresented minorities are often assigned to numerous recruitment activities, panels, and mentorship responsibilities, which results in unequal pressures that are distinct from defined clinical, educational, and research requirements. Often referred to as the “minority tax,” this burden of extra responsibilities placed on minority faculty in the name of diversity can adversely impact promotion of underrepresented minorities within academic medicine.18-22 This tax is complex, and it is a major source of inequity in academic medicine.

Women face similar challenges to minorities, including availability of mentorship, coaching, and sponsorship and disparities in funding.23 Both women and minorities face issues of conscious and unconscious bias. Gender stereotypes and double standards in what is considered an effective leadership style also play a role in promotion disparities.24 Women also face issues of salary disparity and lack of career flexibility.23 Sexual harassment is common in medicine and is underreported for many reasons, including a fear of reprisal.25 Policies and culture surrounding this form of gender discrimination are varied throughout academic medicine. Lastly, institutional and cultural patterns of discrimination and inequities are complex and cannot be separated on the basis of one aspect of a person’s identity or experience.26 Indeed, the challenges that women and minorities face are often amplified by intersecting identities (eg, a gay woman of color will generally have more challenges than a straight white female in academic medicine). The support and guidance underrepresented minorities and women need are nuanced due to these intersecting identities, varied life experiences, and institutional differences. Mentoring teams must be aware of these unique challenges and be proactive in helping their mentee navigate these challenges while advocating for system change.

Limitations

This article only addresses the lack of mentorship and differential exposure to opportunities for leadership among underrepresented minorities and women in academic family medicine. It does not address the representation of the specialty of family medicine in overall leadership positions within medicine and health care systems. Additionally, it does not address specific disparities for additional groups underrepresented in medicine and academic medicine such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) populations and people with disabilities. It is our hope however that these models will be applicable to mentoring and developing leaders in all populations. Furthermore, while our discussions of the obstacles to a diverse leadership were rich, we acknowledge that many additional factors are likely at play in the issues surrounding diversity within the pipeline.

Next Steps

Specific efforts should be made to reach out to underrepresented minorities and women to pull them into the academic family medicine leadership pipeline.27 Identifying potential leaders and providing guidance, coaching, and sponsorship through a multidimensional mentoring team is a suggested first step to increasing diversity. Continued education and intervention to address implicit gender and racial biases and structural racism, which may impact promotional decisions, are important steps to decrease biases towards these groups.28-30 To know if we are being successful in these endeavors, we need to track the current state of minorities and underrepresented leaders within academic family medicine. Using surveys sponsored by the CAFM Education Research Alliance (CERA) is one way to track this in aggregate over time. In addition, CAFM has begun to track data on the number of underrepresented minorities and women in medicine through our member organization databanks to ensure we are making progress. The CAFM Leadership Development Task Force completed its work and gave a final report to CAFM in December 2017. CAFM will continue to develop and disseminate these models for use (with funding support from Family Medicine for America’s Health) through partnership with the American Academy of Family Physicians’ Center for Diversity and Health Equity.

In developing the leadership pipeline, current leaders should look to colleagues, including junior colleagues, who may not have self-identified as leaders but who have demonstrated leadership potential. Building a multidimensional mentoring team can help them reach their potential and will support an increase in the pipeline of future leaders. Using the models developed by the task force, we provide a framework that guides and supports intentional outreach to develop the next generation of leaders.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alan David, MD, Chair of the Department of Family Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, and Robert Graham, MD for their work in the initial discussions to conceptualize Figure 4. The authors also thank Shannon Pittman, MD, who represented program directors on the task force. The authors acknowledge Carlos Jaen and Myra Muramoto for providing breadth of diversity in the perspective of chairs on the Taskforce.

Presentations: Initial versions of the data and figures were presented at the 2017 and 2018 Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conferences:

Kristen Goodell, MD; Jeannette South-Paul, MD; Ardis Davis, MSW; Mary Hall, MD: Leadership Development and Diversity in Academic Family Medicine; Seminar presented at the 2017 STFM Annual Spring Conference. May 5-9, 2017, San Diego, CA.

Stephanie Carter-Henry, MD, MS; Joedrecka Brown Speights, MD; Ardis Davis, MSW; Kerwyn Flowers, DO; Kristen Goodell, MD; Mary Hall, MD; Carrie Pierce, MD; Jennifer Snyder, MD; Jeannette E. South-Paul, MD; Judy Washington, MD; In Pursuit of Equity and Diversity in the Family Medicine Workforce and Leadership; Presented at the 2018 STFM Annual Spring Conference. May 5-9, 2018, Washington, DC.

References

- Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, et al. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):992-1000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2082-9

- Chen FM, Fryer GE Jr, Phillips RL Jr, Wilson E, Pathman DE. Patients’ beliefs about racism, preferences for physician race, and satisfaction with care. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(2):138-143. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.282

- García JA, Paterniti DA, Romano PS, Kravitz RL. Patient preferences for physician characteristics in university-based primary care clinics. Ethn Dis. 2003;13(2):259-267.

- Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, Bindman AB. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(9):997-1004. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.159.9.997

- Xierali IM, Hughes LS, Nivet MA, Bazemore AW. Family medicine residents: increasingly diverse, but lagging behind underrepresented minority population trends. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(2):80-81.

- AAMC. Table A-9: Matriculants to US Medical Schools by Race, Selected Combinations of Race/Ethnicity and Sex, 2015-2016 through 2018-2019. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2018.

- AAMC. Trends: Department Chairs by Chair Type and Sex. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2018.

- Lewellen-Williams C, Johnson VA, Deloney LA, Thomas BR, Goyol A, Henry-Tillman R. The POD: a new model for mentoring underrepresented minority faculty. Acad Med. 2006;81(3):275-279. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200603000-00020

- Afghani B, Santos R, Angulo M, Muratori W. A novel enrichment program using cascading mentorship to increase diversity in the health care professions. Acad Med. 2013;88(9):1232-1238. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829ed47e

- DeCastro R, Sambuco D, Ubel PA, Stewart A, Jagsi R. Mentor networks in academic medicine: moving beyond a dyadic conception of mentoring for junior faculty researchers. Acad Med. 2013;88(4):488-496. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318285d302

- Gottlieb AS, Travis EL. Rationale and models for career advancement sponsorship in academic medicine: the time is here; the time is now. Acad Med. 2018;93(11):1620-1623. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002342

- Roy B, Gottlieb AS. The career advising program: A strategy to achieve gender equity in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):601-602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3969-7

- Travis EL, Doty L, Helitzer DL. Sponsorship: a path to the academic medicine C-suite for women faculty? Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1414-1417. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a35456

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Family Medicine Leadership Development Opportunities. Available at: https://www.stfm.org/facultydevelopment/otherfacultytraining/leadershipdevelopmentopportunities/overview/. Accessed January 15, 2019.15.

- Cropsey KL, Masho SW, Shiang R, Sikka V, Kornstein SG, Hampton CL; Committee on the Status of Women and Minorities, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, Medical College of Virginia Campus. Why do faculty leave? Reasons for attrition of women and minority faculty from a medical school: four-year results. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(7):1111-1118. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2007.0582

- Kaplan SE, Gunn CM, Kulukulualani AK, Raj A, Freund KM, Carr PL. Challenges in recruiting, retaining and promoting racially and ethnically diverse faculty. J Natl Med Assoc. 2018;110(1):58-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2017.02.001

- Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Mouratidis RW. Where are the rest of us? Improving representation of minority faculty in academic medicine. South Med J. 2014;107(12):739-744. https://doi.org/10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000204

- Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9

- Kelly-Blake K, Garrison NA, Fletcher FE, et al. Rationales for expanding minority physician representation in the workforce: a scoping review. Med Educ. 2018;52(9):925-935. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13618

- Pololi L, Cooper LA, Carr P. Race, disadvantage and faculty experiences in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(12):1363-1369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1478-7

- Jimenez MF, Laverty TM, Bombaci SP, Wilkins K, Bennett DE, Pejchar L. Underrepresented faculty play a disproportionate role in advancing diversity and inclusion. Nat Ecol Evol. 2019;3(7):1030-1033. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0911-5

- Carson TL, Aguilera A, Brown SD, et al. A seat at the table: strategic engagement in service activities for early career faculty from underrepresented groups in the academy. Acad Med. 2019;94(8):1089-1093. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002603

- Bates C, Gordon L, Travis E, et al. Striving for gender equity in academic medicine careers: A call to action. Acad Med. 2016;91(8):1050-1052. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001283

- Surawicz CM. Women in Leadership: Why So Few and What to Do About It. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13(12)(12 Pt A):1433-1437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2016.08.026

- Bates CK, Jagsi R, Gordon LK, et al. It is time for zero tolerance for sexual harassment in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):163-165. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002050

- Collins PH. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Revised. New York: Routledge; 1999.

- Peek ME, Kim KE, Johnson JK, Vela MB. “URM candidates are encouraged to apply”: a national study to identify effective strategies to enhance racial and ethnic faculty diversity in academic departments of medicine. Acad Med. 2013;88(3):405-412. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318280d9f9

- Girod S, Fassiotto M, Grewal D, et al. Reducing implicit gender leadership bias in academic medicine with an educational intervention. Acad Med. 2016;91(8):1143-1150. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001099

- Powers BW, White AA, Oriol NE, Jain SH. Race-Conscious Professionalism and African American Representation in Academic Medicine. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):913-915. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001074

- Carnes M, Morrissey C, Geller SE. Women’s health and women’s leadership in academic medicine: hitting the same glass ceiling? J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(9):1453-1462. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2007.0688

There are no comments for this article.