Background and Objectives: Professional identity formation (PIF) is increasingly recognized as a core element of medical education. The use of narrative reflection is traditionally the most common means to explore PIF. We explored the use of mask-making as a process of reflective expression to encourage iterative exploration of professional identity in medical students. This project focused on elements of personal and professional identity in a cohort of entering students.

Methods: One hundred fifty entering students at the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine created a mask to use descriptive words to express their perceptions of an ideal physician (external face of the mask) and their sense of self (internal face of the mask). Responses were compared to established domains of professional identity.

Results: Students most commonly listed elements in the domain of personal characteristics to describe both their sense of self and of an ideal physician. Students were more likely to list emotional elements when describing self and more likely to use elements in the domains of relationships, attitudes, and duties/responsibilities when describing an ideal physician.

Conclusions: The beginning of medical school is a time of significant transition. Mask making can blend visual and narrative arts to provide a complementary tool to examine professional identity formation.

Identity formation is complex and multifaceted.1 Identity formation is a process organizing experiences and relationships into a meaningful whole that incorporates personal, public, and professional senses of self.2 Dynamic and comprised of multiple primary (eg, race, gender) and secondary (eg, medical student, spouse) components, identity is constantly in flux across time and contexts.3 In medical education, professional identity formation (PIF) is a process involving individual psychological development and socialization into appropriate roles and participation in the practice of medicine.4

Transitions in roles naturally lead to changes in identity. Individuals entering medical school do so with multiple and complex subidentities, often trying to adapt to preconceived expectations of what it means to be a medical student.5,6 Professional identity represents the extent to which an individual feels like an authentic member of their professional community.7,8 The PIF process represents a transformative journey where the “knowledge, skills, values and behaviors of a competent, humanistic physician” are integrated into unique individual identities and core values.9 Professional identity evolves through relationships and experiences within contexts, traditions, and ethical foundations of the medical community of practice.10 Ultimately, a strong sense of professional identity is on par with competence, cognition, and skill as an essential element of successful clinical practice.11,12

With this background in mind, we designed an investigation to examine mask-making as a means to describe themes of identity in a cohort of newly matriculating medical students. Masks allow for the external expression of a concern inside or outside of self.13,14,15 Mask-making provides students with “pedagogical space”16 to examine their emerging sense of professional identity.1,17 The process of mask-making allows students to project thoughts and emotions onto the mask to give voice to unsettling worries and concerns.18

In 2017, the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine welcomed an inaugural class to a regional campus in rural central Pennsylvania. As part of orientation, students from the main campus (n=138) gathered with students from the regional campus (n=12). One of the shared activities was a reflective mask-making exercise. Following approval from the institutional review board, students were prompted to use colored permanent markers to describe characteristics of an “ideal physician” on the outside of a blank mask. They were then asked to use the markers to express characteristics describing their sense of self as a beginning medical student on the inside of the mask. While not explicitly instructed to write words on their masks, most students chose to do so.

I transcribed all responses from the exterior (“ideal physician”) and interior of the masks (“self”) to a spreadsheet for analysis. I used basic descriptive statistics for response frequency, then aligned each response with previously reported domains of professional identity.9 Many of the student responses describing “self” did not align with existing domains. Therefore, I added the additional categories of “abilities” and “emotions.”

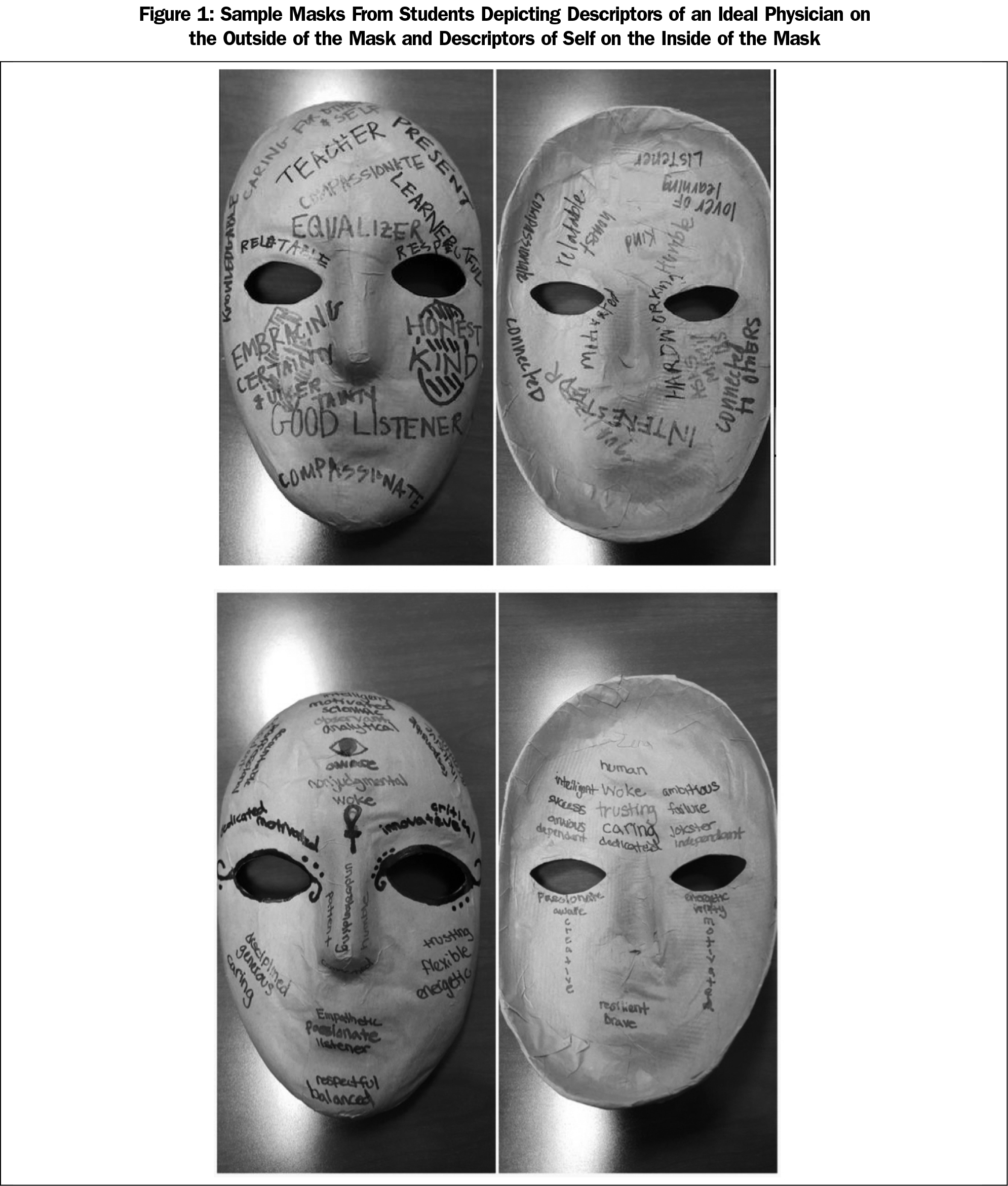

All 150 students participated in the activity. Figure 1 shows sample masks. When describing the ideal physician, elements of personal characteristics (eg, curiosity, intelligence) were the most commonly cited, followed by relationships (eg, collegiality, communication skills). There was an even distribution between domains of attitudes, duties and responsibilities, habits, and perception.

When describing their sense of self as an entering medical student, a different pattern emerged. Personal characteristics remained the most common descriptors (present on nearly half of the masks). Responses diverged from here, however. The next most commonly identified domain dealt with emotions (eg, anxious, excited, eager, overwhelmed). Progressively fewer masks contained descriptors of attitudes (8), habits (8), relationships (7), duties and responsibilities (6), and perceptions (6).

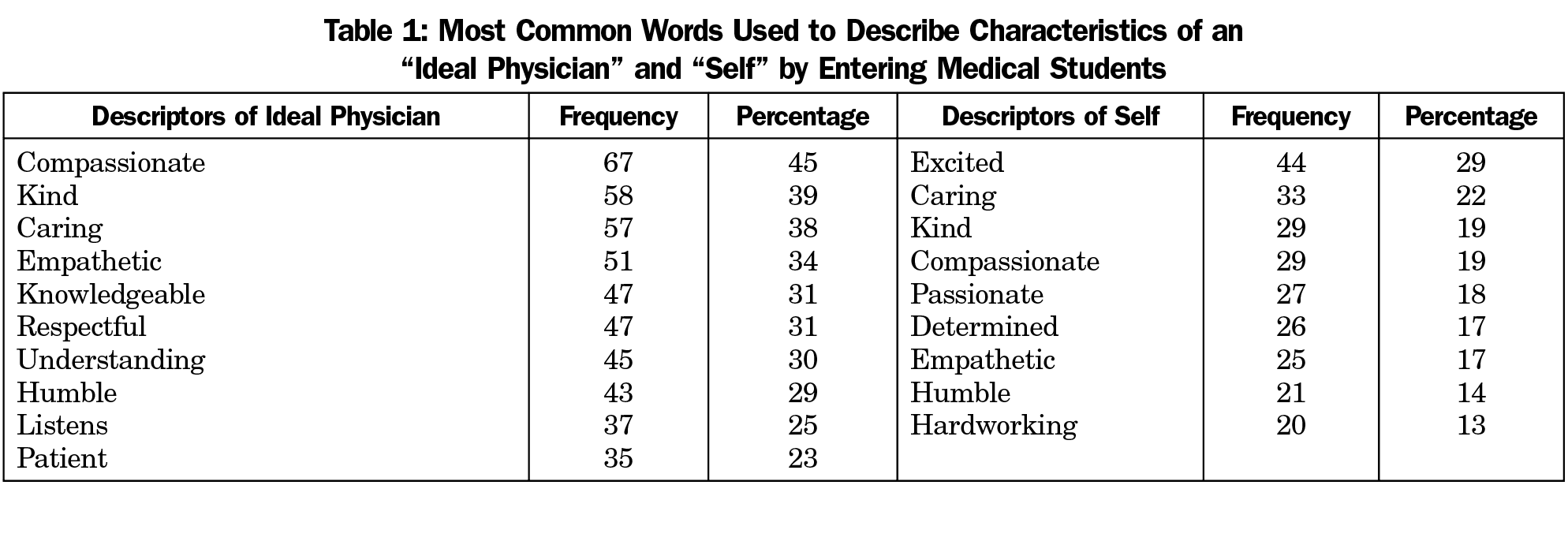

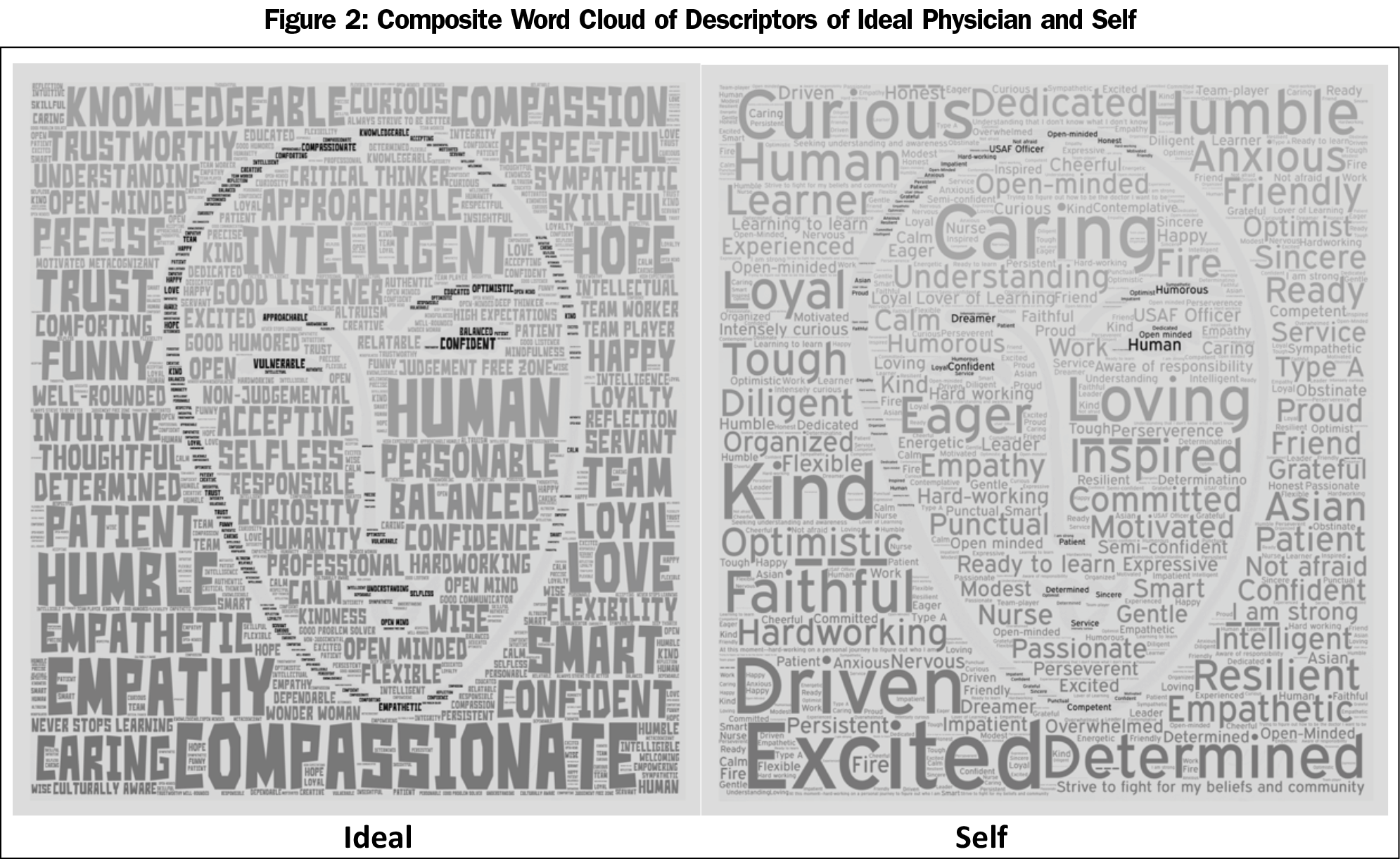

The most frequently listed characteristics are shown in Table 1. By aggregate response frequency, students described the ideal physician as compassionate, kind, caring, empathetic, knowledgeable, respectful, understanding, humble, listening, and patient. In comparison, students described themselves as excited, caring, kind, compassionate, passionate, determined, empathetic, humble, and hard-working. Figure 2 is a visual display of the descriptors that were shared with students.

Masks evolve from the common human need to find meaning and create belonging.19 Mask-making represents a unique way to explore identity as students transition to medical school. Masks are important elements of liminal ritual when “former states are no longer operative and new ones are yet to be conferred.”20 Masks are traditionally used to confirm identity or create a new persona.21 Masks address ambiguities and highlight potential paradoxes in times of transition, allowing the mask maker to explore boundaries and investigate “problems that appearances pose in the experience of change.”22

The masks created as part of this study suggest considerable synchrony between student perceptions of an ideal physician and their perception of self. Compassion, caring, humility, kindness, and empathy were common themes of identity noted for both. In contrast, students were more likely to list relationship (eg, communication skills) and attitudinal (eg, cultural competence) traits when describing an ideal physician. They were more likely to list emotions (eg, excitement, anxiety, enthusiasm) when describing themselves.

This study has several limitations. It is a single-author study that is representative only of a single point-in-time reflection from one cohort of students at one institution. The ability to generalize to other settings is limited. Additionally, the study is purely descriptive. The mask analysis does not take into account placing, position, script, color, font or other nuances that may hold importance to the student-artists who chose to express characteristics through images or symbols. Finally, conducting the exercise in a large-scale public setting may alter how students choose to present their work.

Students often lack a clear view of their professional identity, particularly as they begin their medical education.1 As such, medical schools have the responsibility to provide students with opportunities to develop a sound professional identity allowing them to “think, act, and feel like a physician”23,24 Students must have opportunities to explore identity formation through experience, service, and reflection to promote self-awareness.25 Mask-making represents one way to do so.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance and support of key educational leaders from the Penn State University College of Medicine including Dr Britta Thompson, Dr Dan Wolpaw, Dr Jeff Wong, Dr Michael Flanagan, Dr Terry Wolpaw, Dr Paul Haidet, Dr Jennifer Meka, and Dr Eileen Moser.

References

- Goldie J. The formation of professional identity in medical students: considerations for educators. Med Teach. 2012;34(9):e641-e648. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.687476

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: a guide for medical educators. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):718-725. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700

- Wiese D, Rodriguez Escobar J, Hsu Y, Kulathinal RJ, Hayes-Conroy A. The fluidity of biosocial identity and the effects of place, space, and time. Soc Sci Med. 2018;198:46-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.023

- Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt DD, Regehr G. Competency is not enough: integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1185-1190. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182604968

- Monrouxe LV. Identity, identification and medical education: why should we care? Med Educ. 2010;44(1):40-49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03440.x

- Vivekananda-Schmidt P, Crossley J, Murdoch-Eaton D. A model of professional self-identity formation in student doctors and dentists: a mixed method study. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0365-7

- Holden M, Buck E, Clark M, Szauter K, Trumble J. Professional identity formation in medical education: the convergence of multiple domains. HEC Forum. 2012;24(4):245-255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-012-9197-6

- Wenger E, Snyder W. Communities of practice: the organizational frontier. Harv Bus Rev. 2000;(Jan-Feb):139-145.

- Holden MD, Buck E, Luk J, et al. Professional identity formation: creating a longitudinal framework through TIME (Transformation in Medical Education). Acad Med. 2015;90(6):761-767. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000719

- Coulehan J. Viewpoint: today’s professionalism: engaging the mind but not the heart. Acad Med. 2005;80(10):892-898. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200510000-00004

- Cooke M, Irby DM, O’Brien BC, eds. Educating Physicians: A Call for Reform of Medical School and Residency. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2010.

- Dornan T, Boshuizen H, King N, et al. Experience-based learning: a model linking the processes and outcomes of medical students’ workplace learning. Med Ed 2007; 41(1): 84-91.

- Joseph K, Bader K, Wilson S, Walker M, Stephens M, Varpio L. Unmasking identity dissonance: exploring medical students’ professional identity formation through mask making. Perspect Med Educ. 2017;6(2):99-107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-017-0339-z

- Shapiro J, Youm J, Heare M, et al. Medical students’ efforts to integrate and/or reclaim authentic identity: insights from a mask-making exercise. J Med Humanit. 2018;39(4):483-501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-018-9534-0

- Trepal-Wollenzier HC, Wester K. The use of masks in counseling: creating reflective space. Journal of Clinical Activities, Assignments & Handouts in Psychotherapy Practice. 2002;2(2):123-130. https://doi.org/10.1300/J182v02n02_13

- Atkinson P. Medical Talk and Medical Work: The Liturgy of the Clinic. London: Sage; 1995.

- Ibarra H. Provisional selves: experimenting with image and identity in professional adaptation. Adm Sci Q. 1999;44(4):764-791. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667055

- Green MJ. Comics and medicine: peering into the process of professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):774-779. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000703

- Congdon-Martin D, Pieper J. Masks of the World. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing; 1999.

- Mack J. Masks: The Art of Expression. London, ENG: The British Museum Press; 2013.

- Bontempi, ES. Art Therapy Techniques: Mask Making [Internet]. University of Oklahoma (OK): beyondutopia.net/bontempi/masks_ARTH_bontempi.pdf. Accessed, February 19, 2019.

- Napier AD. Masks, Transformation and Pardox. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1987.

- Merton RK. Some preliminaries to a sociology of medical education. In: Merton RK, Reader LG, Kendall PL, eds. The Student Physician: Introductory Studies in the Sociology of Medical Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1957:3-79. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674366831.c2

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1446-1451. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427

- Inui TS. A Flag in the Wind: Educating for Professionalism in Medicine. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2003.

There are no comments for this article.