Background and Objectives: Medical educators have expressed interest in using less didactic and more interactive formats for academic half-days (AHDs) in postgraduate residency training. We assessed the feasibility and effectiveness of implementing a practice-based small-group learning (PBSGL) process as one part of AHDs.

Methods: A mixed-methods approach was used. Over a two-year period, family medicine residents at the University of Calgary took part in PBSGL sessions during their AHDs, discussing clinical cases presented in evidence-based educational modules and reflecting on clinical experiences with the guidance of a trained peer facilitator. Data sources to explore experiences with the PBSGL process included an evaluation questionnaire, a practice reflection tool (PRT; documenting patient management plans) and individual interviews (n=19) with residents and faculty preceptors.

Results: Of 148 residents, 139 (93%) agreed to participate. Participants were divided into groups of 14-16 members to discuss 12 different module topics. Participants indicated that ongoing small-group interactions were helpful in meeting learning needs and provided opportunities to share and learn from experiences of others in a safe environment. Group facilitation by residents was successful. Level of resident participation and time to preread modules were factors contributing to successful small-group interactions. Modules were rated as effective learning tools, and sample cases were perceived as representing typical cases encountered in practice. Although participants intended to apply their learning to practice, follow through was hindered by lack of relevant clinical cases.

Conclusions: Ongoing small-group learning facilitated by residents, coupled with evidence-based educational materials, was a feasible approach to AHDs.

Postgraduate medical education is situated in clinical environments where residents may not always have adequate exposure to important learning topics. To address this gap, academic half-days (AHDs) have been developed. AHDs are regularly-scheduled educational events under faculty supervision outside clinical time.1 Traditionally, AHDs have focused on didactic presentations, but recently there has been a push for more interactive formats incorporating best educational principles2,3 (opportunities for case-based experiential and social learning, reflection on current approaches, exploration of clinical reasoning, development of self-directed learning approaches).

In 2010, the family medicine (FM) residency program at the University of Calgary made changes to its AHDs based on the educational literature.4-6 To provide an active learning environment the program7,8 “communities-of-learners” were developed by using the process and content of a well-established continuing medical education (CME) program—Practice-Based Small-Group Learning (PBSGL).9 The PBSGL process is based on self-selected groups of physicians meeting monthly with a trained peer facilitator, discussing evidence-based modules on various clinical topics and using a practice reflection tool (PRT)10 to document any planned practice changes resulting from each meeting.9 The goal of PBSGL is to provide a safe learning environment for physicians to reflect on practice and identify gaps between current and best practice. Practice reflections are enhanced through small-group discussions by sharing practice experiences around clinical topics provided in evidence-based educational modules.

This study used a mixed-methods approach11 to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of implementing PBSGL during AHDs, investigate mediators to this learning approach, and determine the impact on intentions related to lifelong learning.

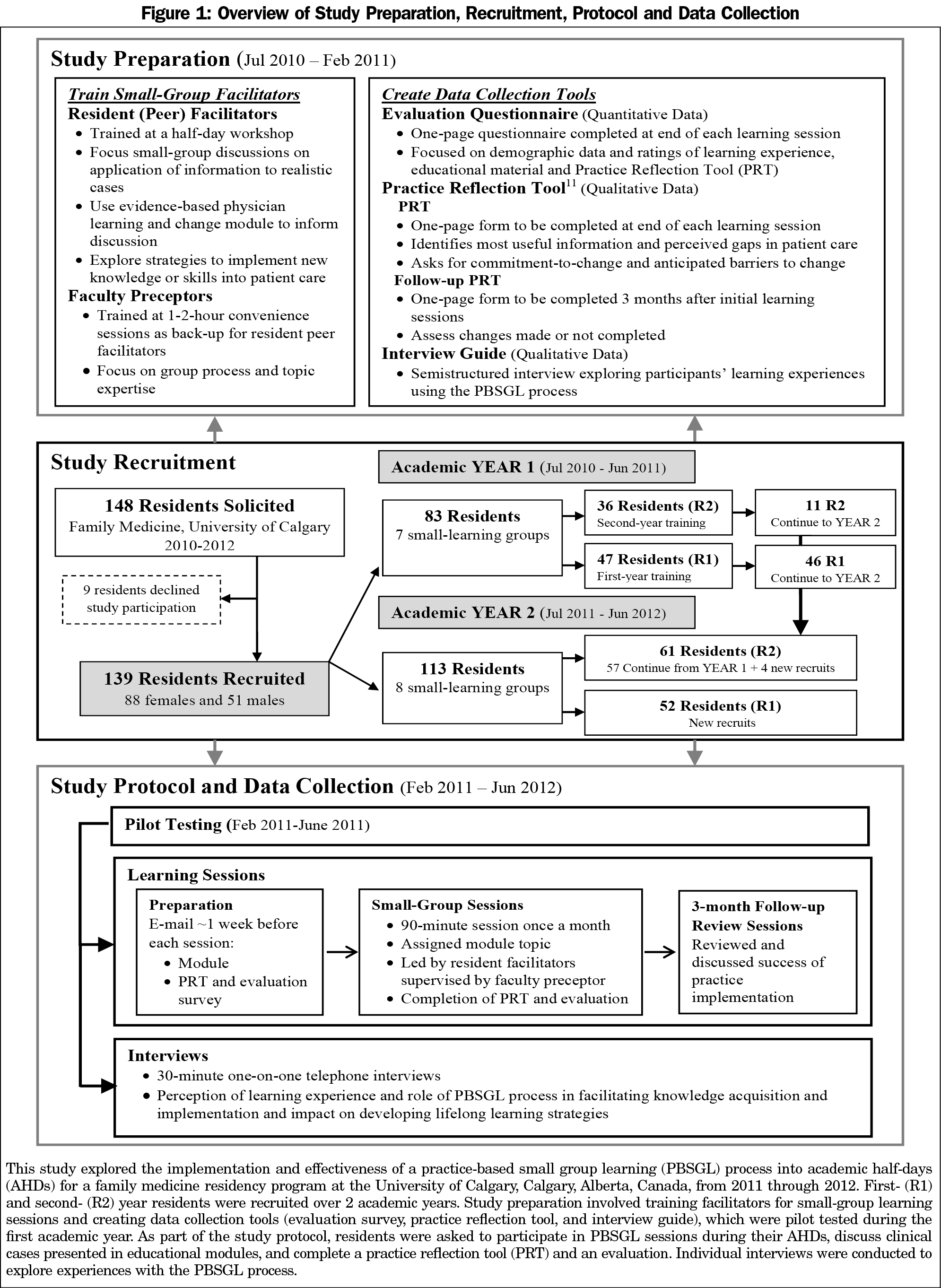

Figure 1 provides an overview of the study recruitment, preparation, protocol, and data collection.

Study Recruitment and Preparation

PBSGL9 was introduced to the University of Calgary FM residency program and studied between 2010 and 2012. Study information and invitations were provided verbally during an AHD and sent via e-mail to all residents (n=148) and faculty (n=23). Initially the study focused on training resident facilitators, creating data collection tools and piloting PBSGL sessions (Figure 1).

Study Protocol and Data Collection

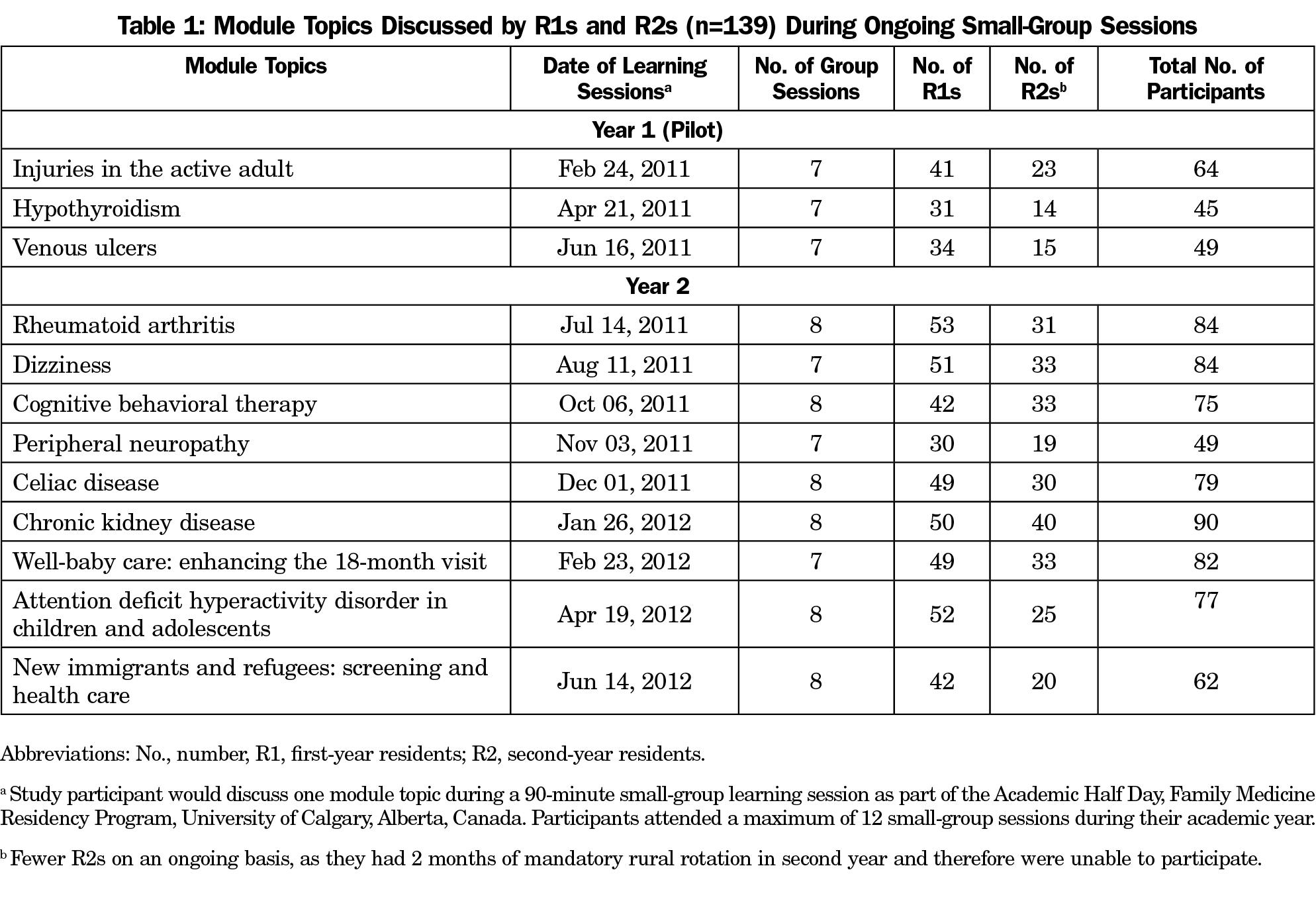

The residency program coordinator assigned residents to groups of 14-16 participants (combined first- and second-year residents) who stayed together over 1-2 years. Participants discussed module topics (Table 1) selected by the academic director during 90-minute PBSGL sessions facilitated by a resident facilitator, and supported by faculty. PBSGL sessions occurred once per month during AHDs.

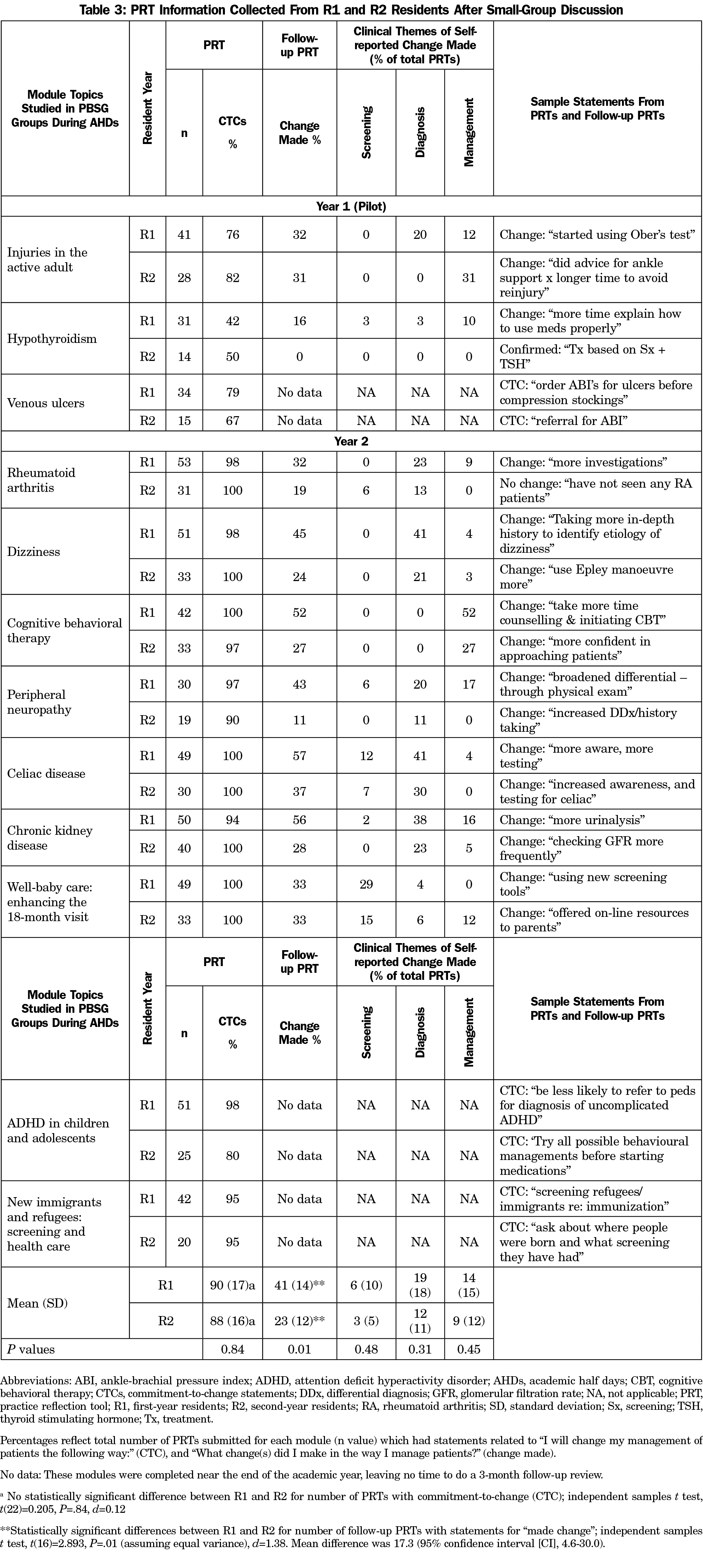

Practice reflection tools were used to document planned practice changes in the form of commitment-to-change statements (CTCs).10,12 Three months after each learning session, groups reviewed CTCs and documented success with implementation in practice (Figure 1). Changes were made to the PRTs (since residents did not perceive themselves as being in practice, the language on the PRTs was changed to “managing my patients”).

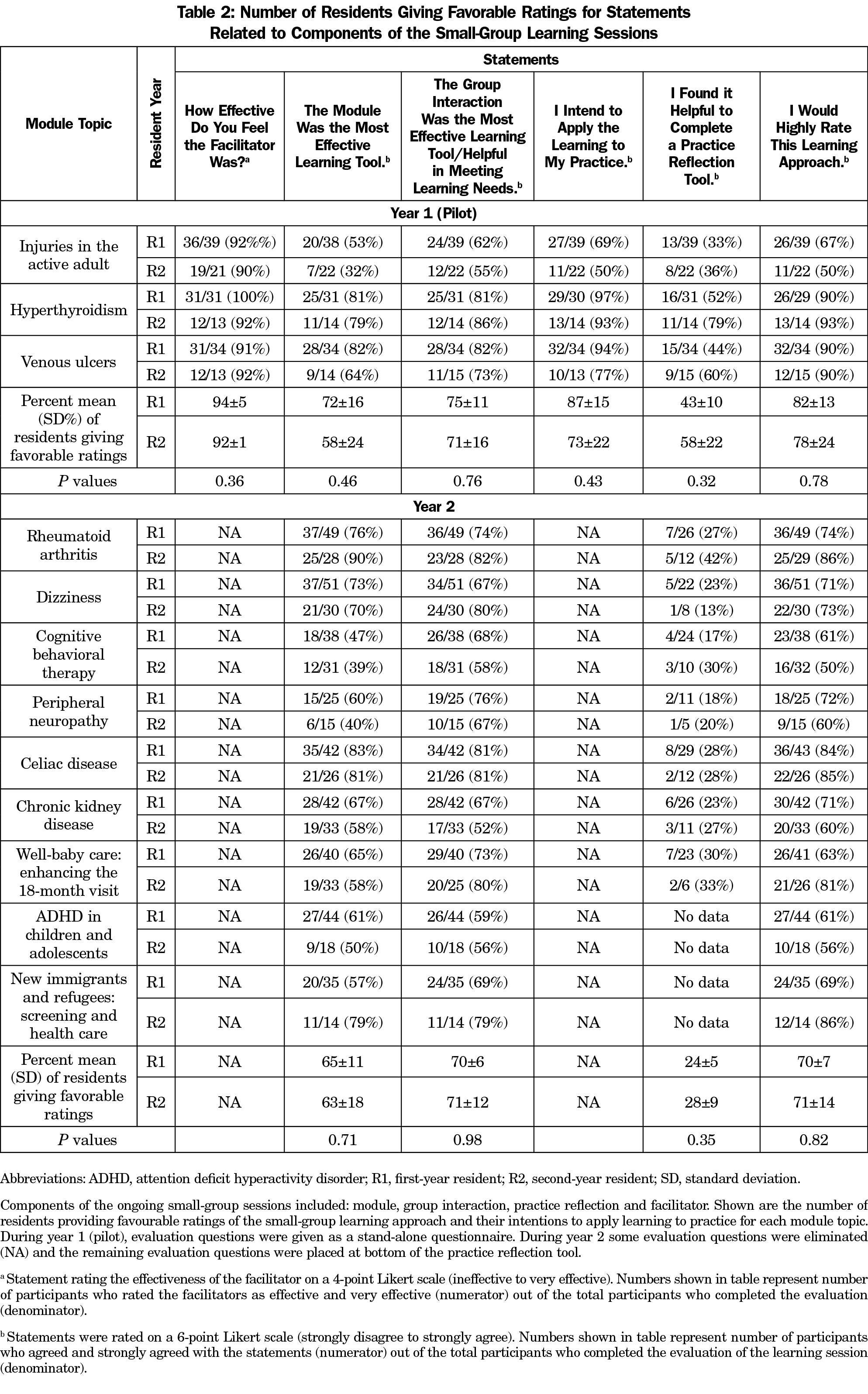

Evaluation questionnaires used to rate the PBSGL sessions consisted of Likert-type questions/statements (Table 2). Participants found completing a separate questionnaire time consuming, so we added selected evaluation questions to the PRTs.

Interviews explored the PBSGL experience. All residents, facilitators, and faculty were invited via e-mail to be interviewed by telephone. Interviews were recorded verbatim for transcription and analyzed using QSR NVivo 9.

Data Analysis

Data from the questionnaires and PRTs were tabulated using Microsoft Excel 2007 for frequency counts and ratio calculations. Independent samples t tests assessed for significant differences (P≤.05) between first- and second-year residents using IBM SPSS Windows Version 24.0.

We coded PRT statements according to a taxonomy of clinical questions,13 and used a thematic analysis approach14 to identify themes and create a framework to code interview statements. Coding discrepancies were discussed until consensus was achieved. Ethics approval was granted by the University of Calgary’s Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board, Calgary, Alberta, Canada: REB E-23666.

Out of 148 residents, 139 (94%) consented to participate (Figure 1). On average, there were nine participants per group. The breakdown of the number of first- and second-year residents who discussed the module topics is shown in Table 1.

Evaluation of Learning Sessions

More participants rated facilitators, modules, and group interactions as effective and indicated intentions to apply learning to practice; no significant differences were observed between first- and second-year residents’ evaluations (Table 2). Fewer residents rated completion of the PRT as helpful.

Practice Reflections and Implementation

Table 3 shows the number of PRTs submitted, percent of documented CTCs, and change made for each module topic. Most participants planned to make changes to patient care. There were no statistically significant differences between the percentage of first- and second-year residents making CTCs. Significantly more first-year residents reported making changes compared to second-year residents; t(16)=2.893, P=.01, d=1.38; mean difference 17.3 (95% CI, 4.6–30.0). Reported changes made were related to diagnosis (eg, ordering tests) and/or management (eg, taking more time to counsel patients) depending on the clinical topic studied (Table 3).

Interviews

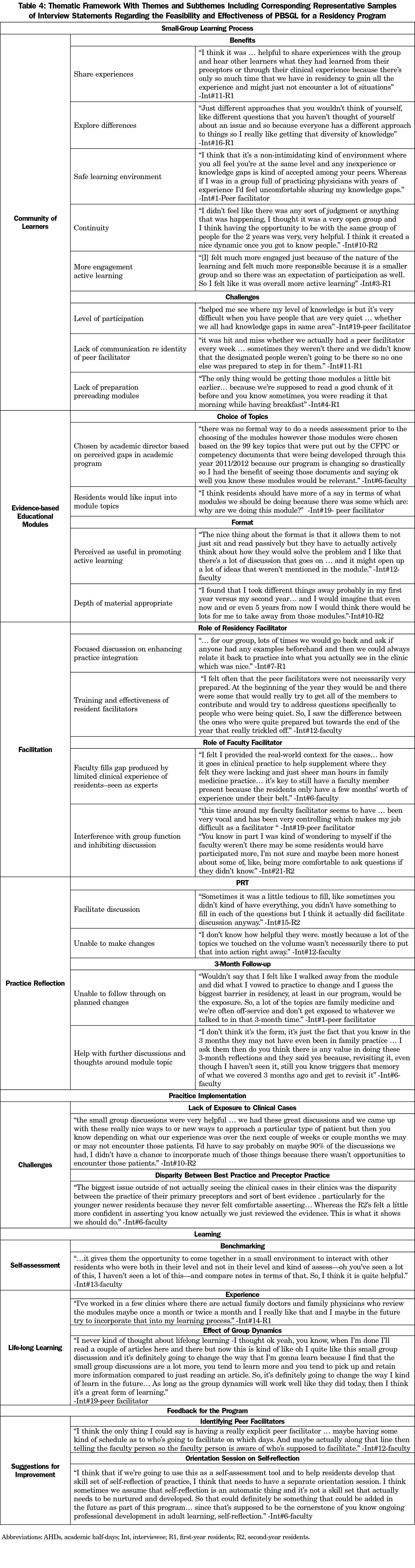

Thirteen residents, three facilitators, and three faculty were interviewed. The thematic framework created to analyze the transcripts had four broad coding categories: (1) small-group learning process, (2) practice implementation, (3) learning; and (4) feedback for the program. Data saturation15 was reached with 14 interviews. Table 4 provides the framework with themes/subthemes and representative interview statements.

Using the PBSGL process during AHDs was found to be a feasible and effective teaching and learning strategy for the University of Calgary family practice residency program.

Developing a community of learners provided an engaging and supportive learning environment. Chen et al7 identified sharing experiences and exploring differences in clinical approaches as factors that increase residents’ engagement in their own learning. Group interactions met participants’ learning needs and improved self-assessment.

Residents’ desire to have input into the choice of modules/discussion topics echoes previous studies.16,17 Considering that modules were developed for established physicians, they were still found to be relevant to the residents’ clinical context. Small-group discussions of patient cases provided opportunities for clinical reasoning, practice reflection, and knowledge application.18 Time to preread modules contributed to successful small-group discussions.

Although facilitators were effective, the peer facilitators’ limited clinical experience hindered discussion around changes in practice. Faculty were meant to fill this gap; however, faculty were resistant to extra training for the PBSGL process. Batalden et al3 identified faculty development as a core principle for developing excellent AHD experiences. To ensure good dynamics within the small-group setting, many facilitation strategies19-21 were discussed during training.

Studies on the use of CTCs in residency are limited.22-24 Using CTCs in this study presented some challenges: residents did not frame their clinical experiences in terms of their practice. They saw themselves as starting to establish clinical approaches for patient management. Even when language was changed, perception of PRT usefulness was questionable. Limited patient encounters minimized opportunities to apply new knowledge. Despite this, most participants planned to apply their learning, and some reported changes to practice. Reviewing planned changes was identified as beneficial to consolidate learning. Although the documented CTCs were similar, first-year residents had more “made changes” statements than second-year residents. This may have been because first-year residents are less experienced than second-year residents, who have already established some practice approaches.

Residents identified the PBSGL experience as one they would seek after residency, and approximately 30% are currently using PBSGL for CME. Rial and Scallan found PBSGL helps newly graduated practitioners shift “their learning needs away from their postgraduate exams and towards ’real world’ practice and establishing a peer group to provide support for the early years in practice.”25 PBSGL appeared to promote practice reflection in the context of small group interactive learning environments, exposing them to a positive lifelong learning environment.

This study is limited by its setting in a single residency program at one university and the focus on one aspect of AHDs. The use of a specific programmatic approach (PBSGL) could be an additional limitation, although the components (consistent small groups; case-based learning materials; facilitated discussions; practice reflections) are relevant and should be tested in other residency programs. The University of Calgary Residency Program continues to use PBSGL during their AHDs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank first- and second-year family medicine residents for participating in this study, and the faculty involved with the family medicine residency program at the University of Calgary for working with the authors to setup ongoing small-group learning sessions as part of the AHDs. They also thank Dr Jacqueline Wakefield and Catherine Leipciger for critical feedback on the manuscript.

This work was presented at the Canadian Conference on Medical Education (CCME) April 14, 2019 in Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada.

Funding: The Department of Family Medicine, University of Calgary provided partial financial support of this project.

References

- Chalk C. The academic half-day in Canadian neurology residency programs. Can J Neurol Sci. 2004;31(4):511-513. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0317167100003735

- Taylor DC, Hamdy H. Adult learning theories: implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 83. Med Teach. 2013;35(11):e1561-e1572. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.828153

- Batalden MK, Warm EJ, Logio LS. Beyond a curricular design of convenience: replacing the noon conference with an academic half day in three internal medicine residency programs. Acad Med. 2013;88(5):644-651. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828b09f4

- Kaufman DM. Applying educational theory in practice. BMJ. 2003;326(7382):213-216. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7382.213

- Edmunds S, Brown G. Effective small group learning: AMEE Guide No. 48. Med Teach. 2010;32(9):715-726. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.505454

- Mann KV. Theoretical perspectives in medical education: past experience and future possibilities. Med Educ. 2011;45(1):60-68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03757.x

- Chen LY, McDonald JA, Pratt DD, Wisener KM, Jarvis-Selinger S. Residents’ views of the role of classroom-based learning in graduate medical education through the lens of academic half days. Acad Med. 2015;90(4):532-538. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000605

- Jung P, Kennedy M, Winder MJ. Protected block time for teaching and learning in a postgraduate family practice residency program. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(6):e323-e329.

- Armson H, Kinzie S, Hawes D, Roder S, Wakefield J, Elmslie T. Translating learning into practice: lessons from the practice-based small group learning program. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(9):1477-1485.

- Armson H, Elmslie T, Roder S, Wakefield J. Encouraging Reflection and Change in Clinical Practice: evolution of a Tool. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2015;35(3):220-231. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.21299

- Creswell J, Clark VLP. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2011.

- Armson H, Elmslie T, Roder S, Wakefield J. Is the Cognitive Complexity of Commitment-to-Change Statements Associated With Change in Clinical Practice? An Application of Bloom’s Taxonomy. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2015;35(3):166-175. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.21303

- Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Gorman PN, et al. A taxonomy of generic clinical questions: classification study. BMJ. 2000;321(7258):429-432. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.321.7258.429

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Walker JL. The use of saturation in qualitative research. Can J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012;22(2):37-46.

- Al Achkar M. Redesigning journal club in residency. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2016;7:317-320. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S107807

- Klein D, Schipper S. Family medicine curriculum: improving the quality of academic sessions. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(2):214-218.

- Bethune C, Brown JB. Residents’ use of case-based reflection exercises. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(3):471-476, 470.

- Azer SA. Challenges facing PBL tutors: 12 tips for successful group facilitation. Med Teach. 2005;27(8):676-681. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590500313001

- Berta W, Cranley L, Dearing JW, Dogherty EJ, Squires JE, Estabrooks CA. Why (we think) facilitation works: insights from organizational learning theory. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):141-154. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0323-0

- Bylund CL, Brown RF, Lubrano di Ciccone B, Diamond C, Eddington J, Kissane DW. Assessing facilitator competence in a comprehensive communication skills training programme. Med Educ. 2009;43(4):342-349. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03302.x

- Trowbridge E, Hildebrand C, Vogelman B. Commitment to change in graduate medical education. Med Educ. 2009;43(5):493. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03353.x

- Ramani S, Mann K, Taylor D, Thampy H. Residents as teachers: Near peer learning in clinical work settings: AMEE Guide No. 106. Med Teach. 2016;38(7):642-655. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2016.1147540

- Mann K, Sargeant J, Hill T. Knowledge translation in interprofessional education: what difference does interprofessional education make to practice? Learn Health Soc Care. 2009;8(3):154-164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-6861.2008.00207.x

- Rial J, Scallan S. Practice-based small group learning (PBSGL) for CPD: a pilot with general practice trainees to support the transition to independent practice. Educ Prim Care. 2013;24(3):173-177. https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2013.11494168

There are no comments for this article.