Background and Objectives: Resident physicians experience a high level of stress. Mindfulness meditation has been shown to offer medical students and physicians a healthier way to relate to daily stressors. We developed and pilot tested a mindfulness training program and assessed its impact on resident physician burnout and resilience.

Methods: The residency program offered 17 family medicine residents a 10-hour mindfulness training over the course of 2 months in 2016. Residents were encouraged, but not mandated, to attend. Experienced Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction teachers and a family physician/integrative health fellow cotaught the program. A research team qualitatively assessed deidentified, postintervention resident interviews. Residents completed four quantitative questionnaires preintervention, immediately postintervention, and 3 months postintervention. A t score was calculated to assess for statistical significance.

Results: Three residents (18%) attended all five training sessions, seven residents (41%) completed at least four sessions, and 16 residents (94%) completed either one or two sessions. Eight residents completed the postintervention interview. Twelve, nine and 14 residents completed the four questionnaires at the three time points, respectively. Qualitative results identified multiple personal/professional benefits of participating in mindfulness training, and we found a statistically significant decrease in perceived stress and increase in mindful awareness from pre- to postintervention (P<.05).

Conclusions: A resident physician mindfulness training program can be reasonably integrated into the residency schedule as part of the wellness curriculum required by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Preliminary results show potential for personal growth and positive changes in patient relationships.

Burnout is characterized by overwhelming exhaustion, feelings of detachment from one’s job, and a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment. Symptoms of burnout are reported by family physicians at a rate significantly higher than other medical specialties (63%) and can result in increased rates of medical errors and lower patient adherence.1,2 A high level of stress-related burnout during residency training is also well documented.3 In our program, we found that 41 out of 42 resident respondents experienced some degree of burnout during training, based on an informal needs assessment.

Mindfulness has been defined as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally,”4 and may allow physicians to cultivate a healthier relationship with stress.5-7 Improvement in self-compassion, empathy,8,9 burnout,1 and positive affect,10 as well as decreased overreactions to stress2 have been reported in mindfulness programs for resident physicians. Research indicates that brief programs may be beneficial.11,12 As part of our efforts to support resident well-being and professional development, we assessed the impact of a 10-hour training program on residents’ burnout experiences.

Program Development and Participants

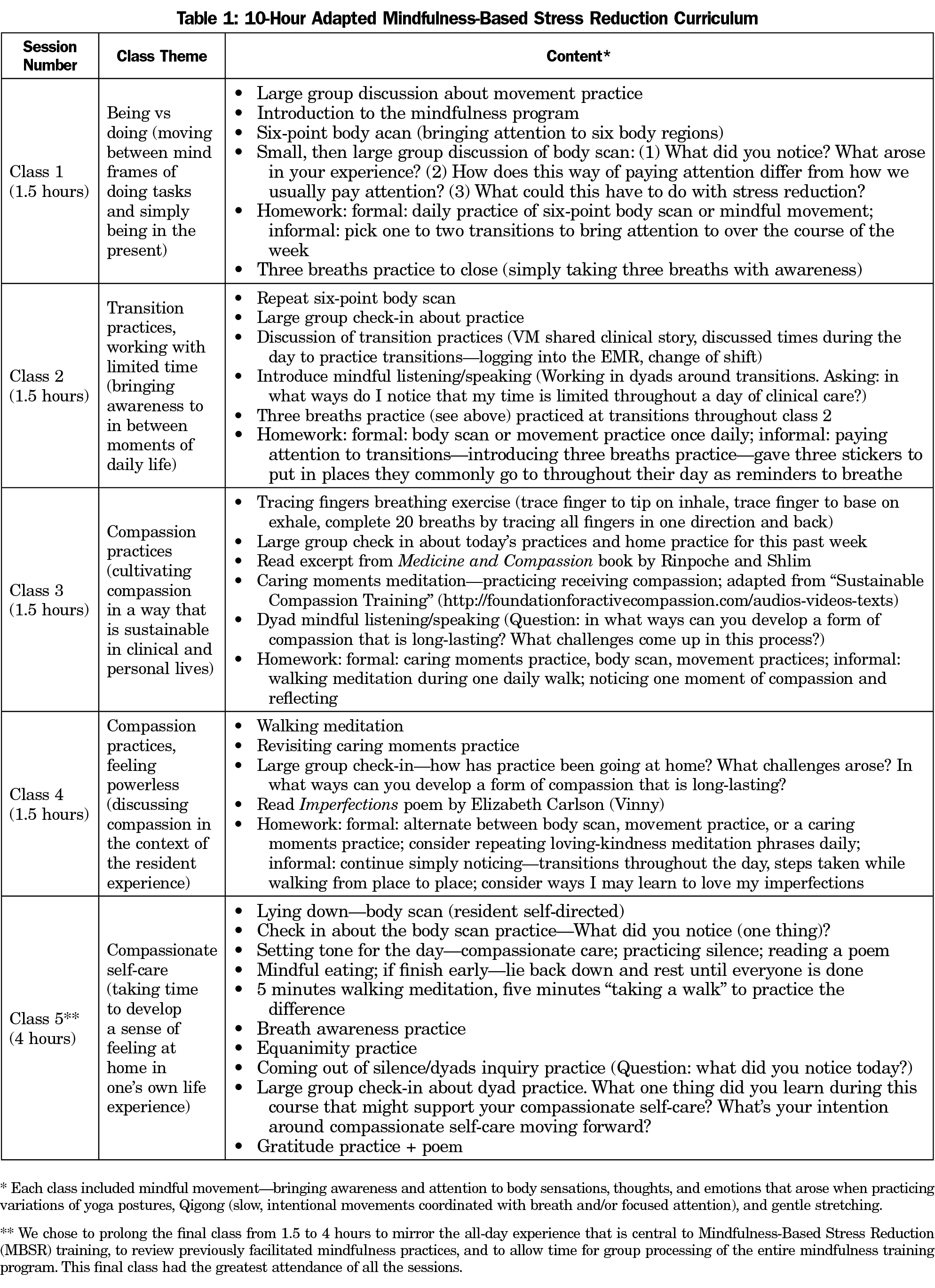

We designed a five-session, 10-hour curriculum (Table 1). Participation was strongly encouraged for 17 first-year family medicine residents. The training occurred during scheduled didactic time on a weekly or biweekly basis in fall 2016. The University of Washington Health Sciences Minimal Risk Institutional Review Board exempted this educational study.

Qualitative Assessment

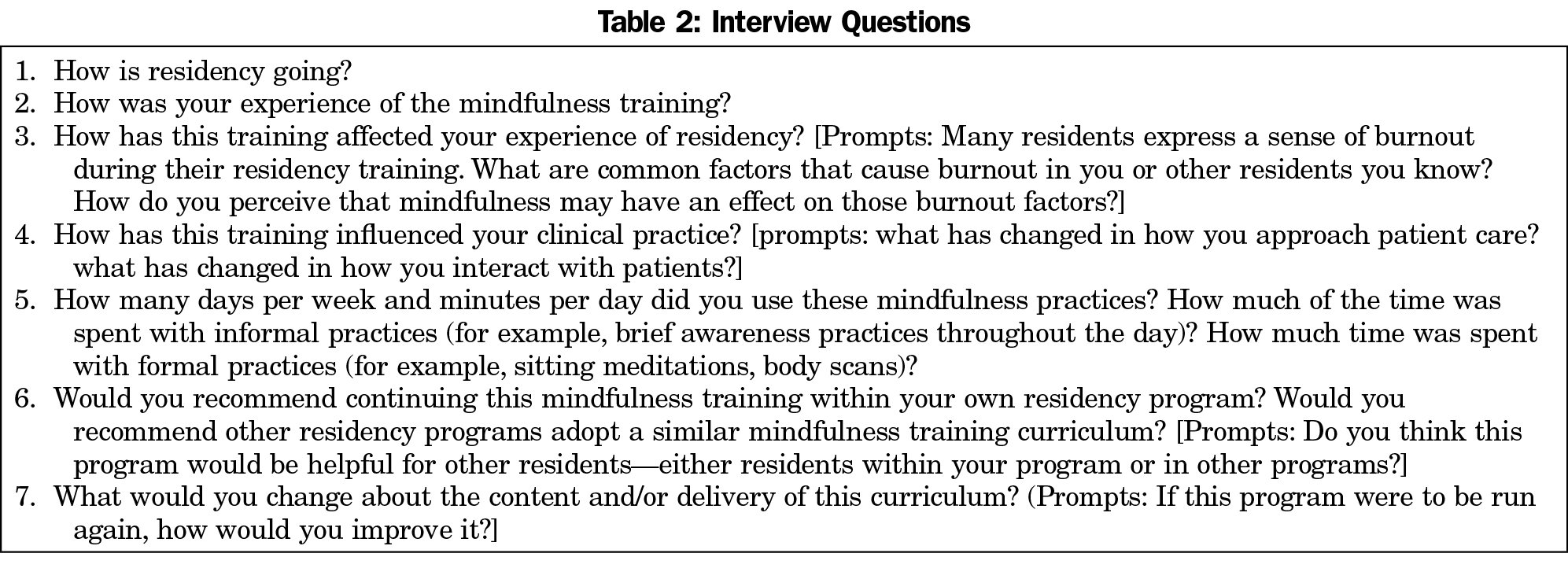

Residents were invited to participate in confidential, posttraining phone interviews (Table 2) with optional recording conducted by a physician-researcher (author S.H.) not associated with the training. Responses were transcribed.

Transcripts were read by six reviewers: four integrative health fellows (including V.M.), a family physician with a doctorate degree in anthropology (B.B.), and a senior mindfulness instructor. Prior to reviewing transcripts, all readers went through a bracketing process in which they answered a series of reflective questions on their sociocultural background and relationship with the subject matter. Reflection fosters awareness of readers’ strengths and/or limitations that result from their backgrounds, thus improving the quality of the reviewing process. Readers reviewed transcripts twice, following a modified interpretative phenomenological analysis approach.13 Readers met to discuss notations and emergent themes during six in-person meetings.

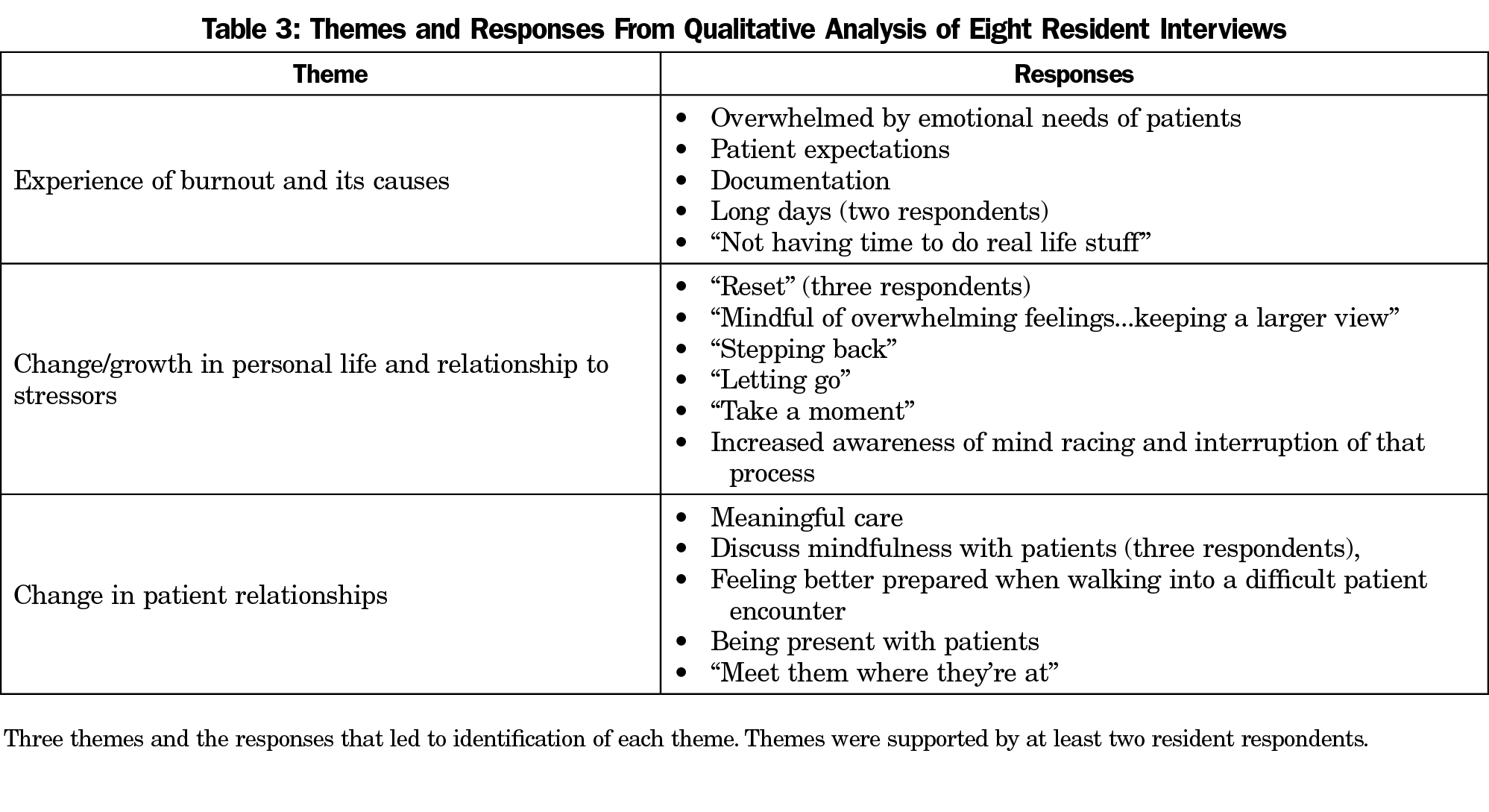

The lead investigator (V.M.) condensed the themes (Table 3), shared results with all readers, and conducted one member-checking session with six residents. There were no disagreements among readers or residents with the condensed themes.

Quantitative Assessment

Residents completed surveys prior to the mindfulness training, immediately afterwards, and 3 months posttraining. Surveys included the Maslach Burnout Inventory,14 Perceived Stress Scale-10,15 Brief Resilience Scale (assessing one’s ability to bounce back from stress),16 and Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (measuring an individuals’ experience of mindfulness).17 These measures feature prominently in burnout and mindfulness literature, have a short completion time (15 minutes), and encompass outcomes of interest. Qualtrics online survey software (Provo, UT: Qualtrics; 2018) was utilized to collect and organize the data.

Data were compared on each measure from baseline to 2- and 5-month values and between 2- and 5-month values, and tested for significance using unpaired, two-sample t tests. Self-report bias was minimized by ensuring anonymity.

Of the 17 first-year family medicine residents, 10 participated in at least four of the five sessions, and 16 completed one or two sessions.

Qualitative Assessment

Eight residents completed postintervention interviews, and saturation was reached after reviewing these interviews. Reviewers identified three themes during qualitative analysis: (1) experiences of burnout and its causes, (2) change/growth in personal life and relationship to stressors, and (3) changes in patient relationships (Table 3).

Residents provided positive programming feedback including: (1) appreciating the community space provided to practice mindfulness, (2) participating in a training rather than check-in discussion groups, (3) holding sessions during the first year of residency, and (4) one of the teachers (V.M.) was a family physician. One point of contention amongst respondents was about whether the program should be mandatory or voluntary.

Quantitative Assessment

Eight residents completed all measures at all three time points (Table 4). Average scores showed significant improvement in depersonalization, perceived stress, and experience of mindfulness. All respondents moved out of the “high levels of burnout” range in the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization subscales.

We implemented a mindfulness program during residency training. Most residents (59%) voluntarily attended at least four of the five sessions. Both qualitative and quantitative assessments suggest that this program may improve burnout, resilience, perceived stress, and level of mindful awareness, while having positive influences on residents’ personal lives and clinical practice. Positive responses about the training format and content provide support for the program, and the likelihood of implementing and evaluating similar programs.

Our program is the first to quantitatively and qualitatively assess a brief mindfulness curriculum for resident physicians that is integrated into residency training. Quantitative results suggest that participating residents noticed lower amounts of depersonalization and perceived stress in their work, while incorporating a greater understanding of mindfulness meditation into their lives. These data are corroborated in the residents’ interviews as they acknowledge a shift in their relationships to stressors—a shift that carried over into their personal and professional lives.

Study strengths included collaboration of readers from diverse backgrounds, the use of a bracketing process, incorporating resident feedback, and group facilitation by experienced mindfulness teachers. Finally, as a training embedded within a standard didactic curriculum, our program avoided adding responsibilities to the already full lives of resident physicians, supporting healthy physician learning and practice.18-20

This study had several limitations. This was a small-scale observational study with no control group. Rotation scheduling constraints prevented some residents from attending classes. Attendance was not tracked to support resident privacy, so we could not assess any association between attendance and the quantitative measures over time, nor can we conclude that regular attendance is associated with congruent benefits described in the qualitative assessment.

This study describes a mindfulness program for resident physicians. Our findings suggest this program can be reasonably integrated into the residency curriculum, and that mindfulness may be an effective way for residents to enhance resilience, and prevent and navigate burnout.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude for the collaborative efforts and support of the UW Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, the UW Integrative Health program, and the UW Health Mindfulness Program. The authors thank Shari Barlow for her work in project management, in addition to continued support of the process involved in coordinating this resident mindfulness curriculum. They also thank Mindy Smith, MD, for her contributions through editing and advising on this manuscript.

Financial Support: The University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Family Medicine and Community Health (UW-DFMCH) Small Grants Program contributed funding for this projec,t in addition to the UW Integrative Health program’s George Washington Institute for Spirituality and Health grant. During this project, Bruce Barrett was supported by a midcareer research and mentoring grant from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (K24AT006543).

Presentations: Minichiello V. Being with burnout: the development and evaluation of a 10-hour mindfulness training for resident physicians. University of Cincinnati, Hematology/Oncology Grand Rounds Presentation. Cincinnati, OH. May 18, 2018.

Minichiello V. Developing an adapted mindfulness based stress reduction program for resident physicians. Guest speaker at Madison, Wisconsin VA Hospital’s monthly Integrative Health and Wellness Committee meeting. June 14, 2017.

Minichiello V. Being with burnout. University of Wisconsin, Anesthesiology Grand Rounds Presentation. Madison, WI. October 10, 2018.

Minichiello V. Introduction to STREaM: Supportive Training for Residents through Education in Mindfulness. University of Wisconsin, Madison, Graduate Medical Education Committee Meeting. Madison, WI. October 17, 2018.

References

- Goldhagen BE, Kingsolver K, Stinnett SS, Rosdahl JA. Stress and burnout in residents: impact of mindfulness-based resilience training. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:525-532.

- Brennan J, McGrady A. Designing and implementing a resiliency program for family medicine residents. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2015;50(1):104-114. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091217415592369

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-451. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134

- Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life. 10th ed. New York: Hachette Books; 2005.

- Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1284-1293. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1384

- Fortney L, Luchterhand C, Zakletskaia L, Zgierska A, Rakel D. Abbreviated mindfulness intervention for job satisfaction, quality of life, and compassion in primary care clinicians: a pilot study. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(5):412-420. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1511

- Goodman MJ, Schorling JB. A mindfulness course decreases burnout and improves well-being among healthcare providers. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2012;43(2):119-128. https://doi.org/10.2190/PM.43.2.b

- Runyan C, Savageau JA, Potts S, Weinreb L. Impact of a family medicine resident wellness curriculum: a feasibility study. Med Educ Online. 2016;21(1):30648. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v21.30648

- Verweij H, van Ravesteijn H, van Hooff MLM, Lagro-Janssen ALM, Speckens AEM. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Residents: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(4):429-436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4249-x

- Wen L, Sweeney TE, Welton L, Trockel M, Katznelson L. Encouraging Mindfulness in Medical House Staff via Smartphone App: A Pilot Study. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(5):646-650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-017-0768-3

- Carmody J, Baer RA. How long does a mindfulness-based stress reduction program need to be? A review of class contact hours and effect sizes for psychological distress. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(6):627-638. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20555

- Romcevich LE, Reed S, Flowers SR, Kemper KJ, Mahan JD. Mind-Body Skills Training for Resident Wellness: A Pilot Study of a Brief Mindfulness Intervention. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2018;5:2382120518773061. https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120518773061

- Smith JA, Flowers P, Larkin M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis : theory, method and research. [Internet] London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2009, Available from https://trove.nla.gov.au/version/164877353. Accessed November 1, 2018.

- Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual [Internet]. 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996 [cited 2018 Nov 1]. https://trove.nla.gov.au/version/18762965. Accessed July 18, 2019.

- Cohen S. Perceived Stress Scale—Mind Garden [Internet]. Menlo Park, CA: Mind Garden, Inc; 1994. http://www.mindgarden.com/documents/PerceivedStressScale.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2018.

- Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15(3):194-200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13(1):27-45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504

- Konopasek L, Slavin S. Addressing Resident and Fellow Mental Health and Well-Being: What Can You Do in Your Department? J Pediatr. 2015;167(6):1183-4.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.09.037

- Ludmerer KM, Johns MME. Reforming graduate medical education. JAMA. 2005;294(9):1083-1087. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.9.1083

- Verweij H, van Ravesteijn H, van Hooff MLM, Lagro-Janssen ALM, Speckens AEM. Does Mindfulness Training Enhance the Professional Development of Residents? A Qualitative Study. Acad Med. 2018;93(9):1335-1340. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002260

There are no comments for this article.