Background and Objectives: Morbidity and mortality conference (MMC) is educationally important. However, resident physicians rate it less positively than faculty, citing focus on assigning blame rather than targeting change. Additionally, many MMC presentations are selected for clinical novelty instead of avoidable outcome. Despite significant time and resources routinely committed to MMC, its educational and clinical impact is generally limited. This warrants shifting focus toward quality improvement and systems-based care.

Methods: From July to December 2017, within a large, public academic center and medical school, the family medicine MMC became a quality conference (QC) focusing on thematically-linked, system-based errors. After case presentations, the audience split into small groups for targeted discussion then reconvened to identify specific interventions. We collected attitudinal data from faculty and resident physicians in attendance using real-time audience text polling, targeting case relevance and change impact.

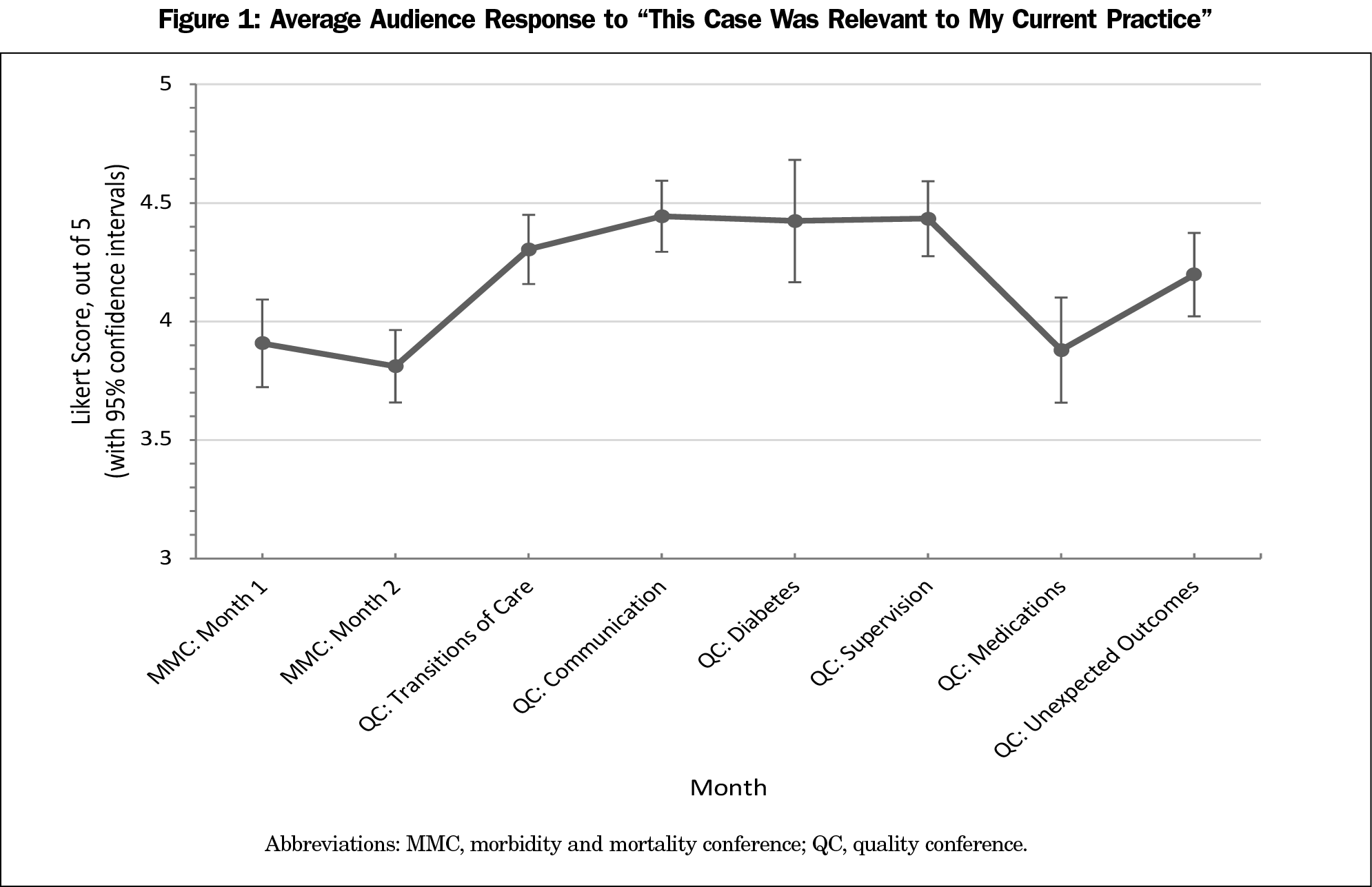

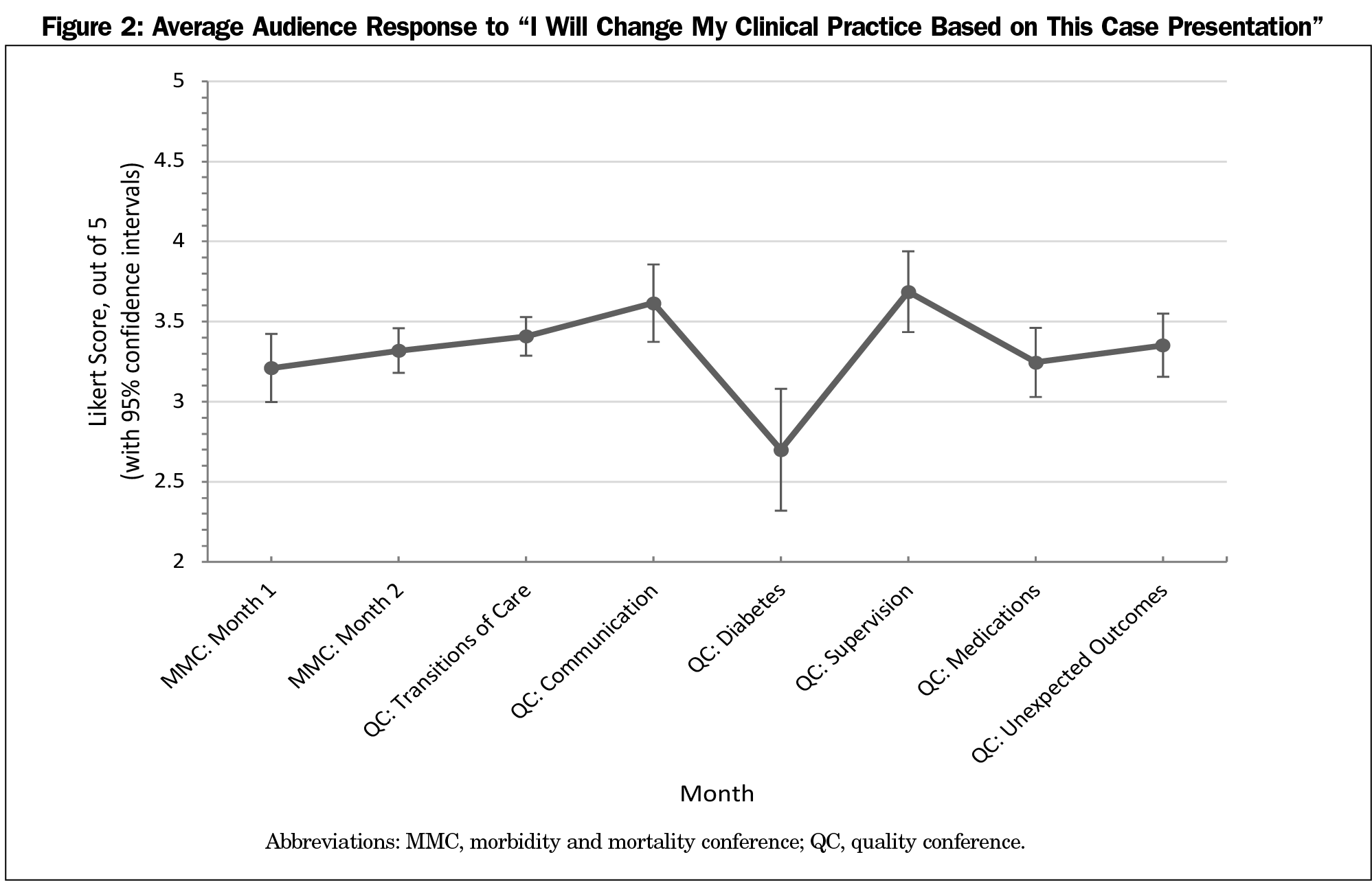

Results: Compared to MMC, QC case relevance improved by 0.39 (P<.01) on a 5-point scale. Compared to MMC, QC cumulatively approached but did not meet statistical significance regarding changing clinical practice. Qualitative statements commented on increased multilevel engagement, dedicated follow up, and decreased didactic presentations.

Conclusions: QC demonstrated statistically significant increased relevance compared to MMC, reflecting the benefit of systems-based, thematically-linked cases.

The morbidity and mortality conference (MMC) is a long-standing medical education tool meant to teach from adverse outcomes. However, resident physicians rate it less positively than faculty, citing focus on deflecting and assigning blame.1 Additionally, many MMC cases are selected primarily for clinical novelty.2 Highlighting upstream, systems-level cause and effect would be more objective.3 There have been efforts to shift MMC toward quality improvement and systems-based care,4,5,6,7 at the expense of didactics-driven learning.

We hypothesized implementing a theme-based, systems-focused quality improvement conference would increase relevance and likelihood to change clinical practice, thus increasing its medical educational value.

This project took place at the Michigan Medicine Department of Family Medicine, comprising 99 faculty and 33 resident physicians at a publicly-funded academic medical center. The University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board deemed the project exempt from review (HUM00145938).

MMC was a monthly 2-hour conference presented by senior residents from each inpatient service, reviewing their month’s short list of cases (typically interesting cases and suboptimal outcomes), prepared concurrent to their inpatient responsibilities. Short list paper copies were distributed at each MMC. Occasionally, faculty members presented an outpatient case.

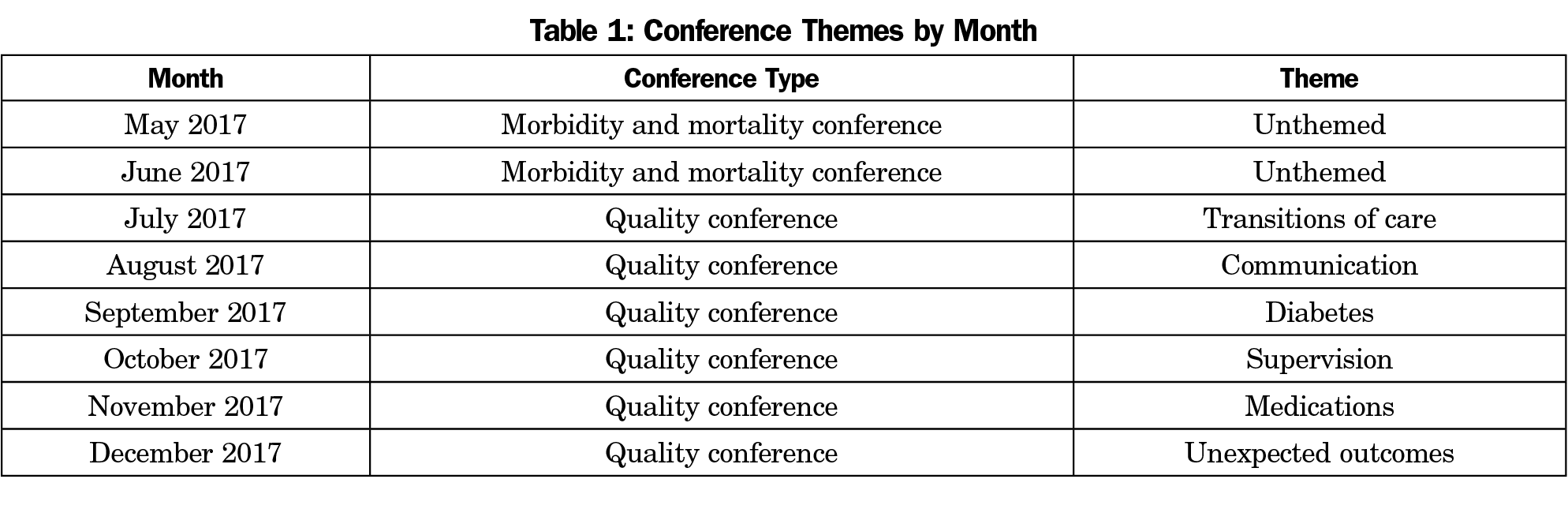

Starting in July 2017, we began a 6-month pilot, changing MMC to a systems-focused quality conference (QC), without changing frequency or duration. We selected conference themes to demonstrate different types of error (Table 1) and vetted each resident-selected case for thematic and systems-focused appropriateness. Inpatient seniors continued to compile short lists stored on an institution-approved, online repository. Residents on assigned outpatient rotations each received oversight from study authors and administrative time to prepare their QC presentations. At QC, each resident presented one case, from past short lists or personal experience, culminating in discussion prompts identifying systems flaws. After brainstorming solutions in small groups, audience members reconvened to discuss high-impact, low-cost interventions. These became standing agenda items at the department’s Quality Improvement Committee for implementation; workflow crossover did not previously exist. A status report on these proposals was presented at the pilot’s conclusion.

We collected data from May 2017 through June 2017 about MMC as a baseline, and from July 2017 through December 2017 to assess QC. We collected attitudinal data using voluntary, anonymous, real-time audience text polling. We assessed attitudes regarding case relevance and change impact via a targeted 5-point Likert scale (1-strongly disagree to 5-strongly agree) text prompt. We collected qualitative attitudinal data via free-text submission. Study authors iteratively adjusted QC based on feedback reviewed each conference session. Resident physicians also submitted written feedback in their annual program evaluation. Electronic attendance logs provided attendance data.

We analyzed quantitative data using Stata and compared using two different linear regressions, one with Likert-scale responses to the relevance question as the dependent variable and one with Likert scale responses to the change practice question as dependent variable. Both regressions included a dichotomous independent variable representing conference type (MMC vs QC). All analyses included clustering by conference session. A sensitivity analysis using dichotomized outcomes and logistic regression yielded similar results.

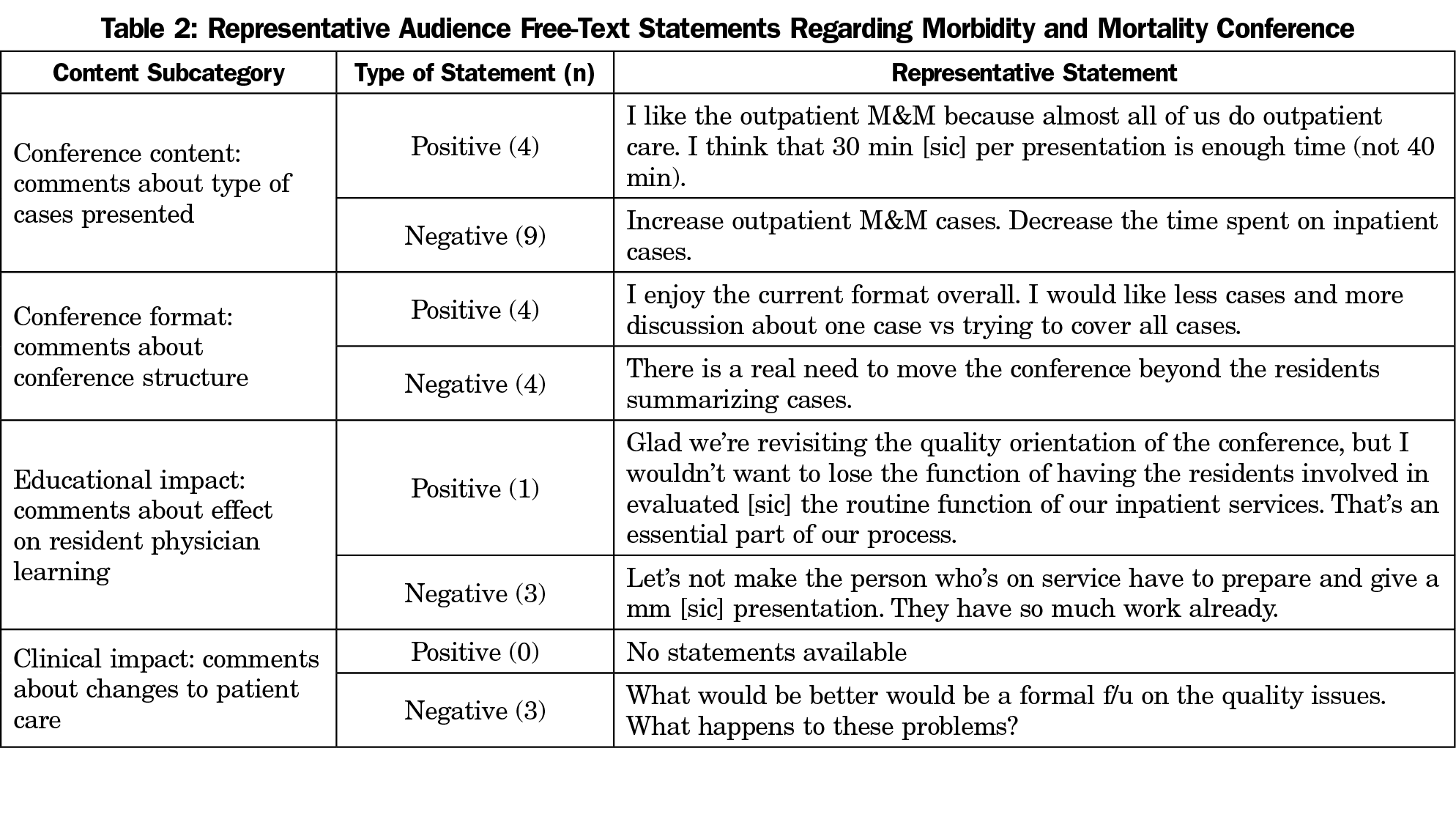

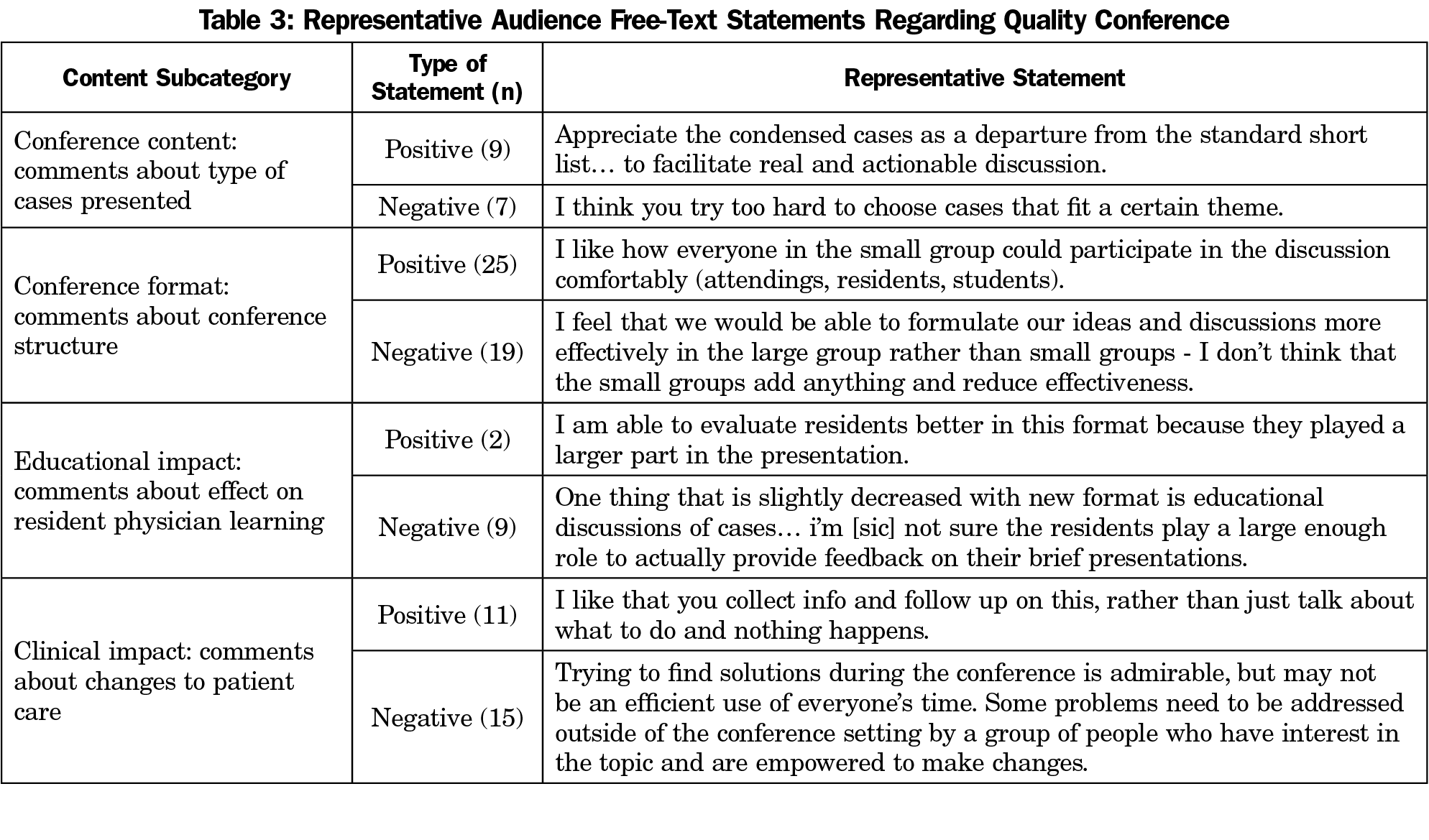

Two authors independently sorted and categorized qualitative comments (conference content, conference format, educational impact, and clinical impact); discrepancies were mutually reassessed and resorted. We then compared and contrasted comments in each subcategory by educational format.

There were 720 responses to the prompt “This case was relevant to my current practice.” Compared to MMC, QC case relevance improved by 0.39 (P<.01, 95%CI [0.24-0.53]), indicating a moderate effect size (Figure 1). There were 715 responses to the prompt “I will change my clinical practice based on this case presentation.” Compared to MMC, QC did not meet statistical significance regarding changing clinical practice (diff=0.14, P=.072, 95%CI [-0.01-0.30]; Figure 2).

Each QC month was uniquely themed (Table 1). Transitions of care, communication, diabetes, and supervision months were each rated more relevant (P<.05) than MMC months.

High case relevance did not predict likelihood to change clinical practice, but lack of relevance precluded practice change. Diabetes month was rated highly relevant (4.42/5, 95%CI [4.17-4.68]), but was rated least likely to change clinical practice (2.7/5, 95% CI [2.32-3.08]). Conference attendance remained unchanged.

We received 28 statements regarding MMC and 97 statements about QC (Tables 2 and 3). There were differing opinions, especially concerning QC small group discussions. Comments predominantly favored small groups for encouraging multilevel participation; dissenting comments cited decreased efficiency. Other comments addressed concern over decreased didactic presentations and appreciation regarding follow up.

Excerpts regarding QC in the residents’ annual program evaluation are as follows:

The residents are thrilled with the recent changes in quality conference. …we acknowledge differing opinions about breaking into small groups but reached consensus despite the occasional discomfort this is a valuable model…. Some residents do feel that the conferences have suffered from moving too far away from the didactics and medically interesting cases…

QC demonstrated increased case relevance compared to MMC (P<.01). QC achieved near statistical significance regarding change practice (P=.072). This may suggest benefit in systems-focused, thematically-linked case presentations, since increased relevance may increase the educational applicability of these conferences.

Resident physicians expressed appreciation for implemented changes, and education-focused feedback informed iterative adjustments. We favored continued use of small groups to increase inclusion. Concern about decreased learning prompted reintroduction of brief didactic presentations, without losing focus on systems-based errors.

Redesigning MMC exposed numerous challenges in changing systems and department culture. Balancing requests from clinical, residency, and executive stakeholders within practical limitations required extensive consensus building. Our study only lasted 6 months to balance conflicting stakeholder concerns. Importantly, while data collection terminated after 6 months, QC was formally adopted by our department and continues monthly.

Limitations affecting QC data include pilot starting with the new academic year and variable presenter skill. In addition, audience members who felt strongly about MMC/QC may have been more likely to submit responses.

Future steps include streamlining case solicitation from peer review committees and increasing resident involvement in the postpresentation quality improvement process.

Our study’s main conclusions highlight the overall well-received transition to thematically-linked, systems-based QC, with improved relevance to clinical practice and increased resident physician satisfaction. Implications include proof of concept regarding positive change to MMC, while maintaining its spirit of practice reflection.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: Richardson C, Chiang C, Greenberg J. From anecdotes to systems-based changes: redesigning the morbidity and mortality conference. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference. Toronto, Ontario, Canada; April 30, 2019.

References

- Harbison SP, Regehr G. Faculty and resident opinions regarding the role of morbidity and mortality conference. Am J Surg. 1999;177(2):136-139. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9610(98)00319-5

- Biddle C, Oaster TR. Investigating the nature of the morbidity and mortality conference. Acad Med. 1990;65(6):420. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199006000-00019

- Ishikawa K. What is Quality Control the Japanese Way. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1985.

- Kim C, Fetters MD, Gorenflo DW. Residency education through the family medicine morbidity and mortality conference. Fam Med. 2006;38(8):550-555.

- Deis J, Smith K, Warren M et al. Transforming the Morbidity and Mortality Conference into an Instrument for Systemwide Improvement. Advances in Patient Safety. (Vol. 2: Culture and Redesign). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008 Aug.

- Fussell JJ, Farrar HC, Blaszak RT, Sisterhen LL. Incorporating the ACGME educational competencies into morbidity and mortality review conferences. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(3):233-239. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401330903018542

- Cifra CL, Bembea MM, Fackler JC, Miller MR. Transforming the Morbidity and Mortality Conference to promote safety and quality in a PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17(1):58-66. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000000539

There are no comments for this article.