Background and Objectives: Although the subinternship (sub-I) is considered integral in many medical schools’ curricula, family medicine does not have standardized course recommendations. Given the variable nature of this clinical experience, this study investigated the potential role of a standardized sub-I curriculum in family medicine.

Methods: Questions about sub-Is were created and data were gathered and analyzed as part of the 2019 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine clerkship directors. The survey was distributed via email to 126 US and 16 Canadian recipients between June 19, 2019 and August 2, 2019 through the online program SurveyMonkey.

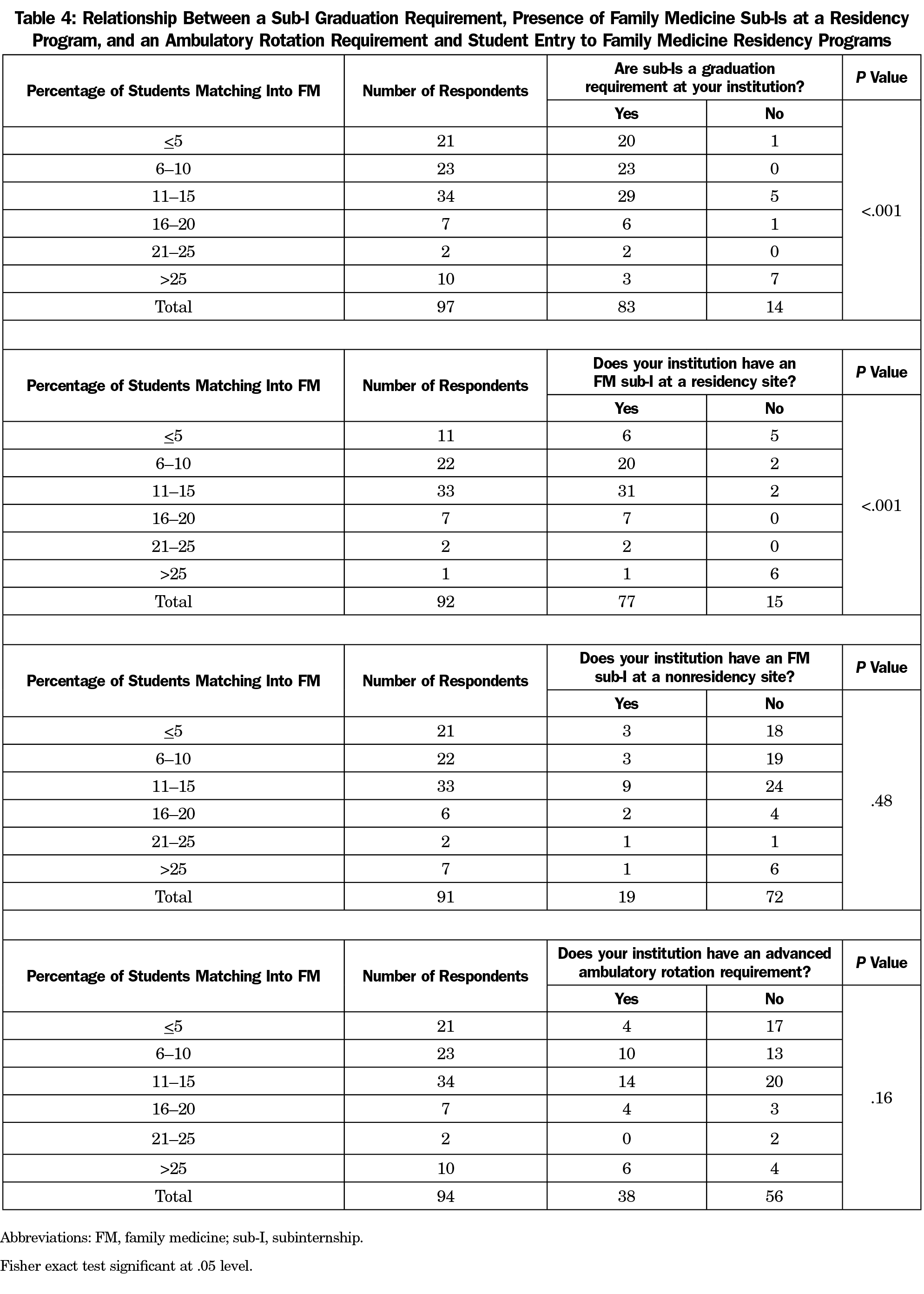

Results: A total of 101 (71.1%) of 142 clerkship directors responded to the survey. Most (84.2%) schools require sub-Is. There was a positive association between students matching into family medicine and having family medicine sub-Is at residency programs (P<.001). There was no relationship between higher family medicine match rates and the presence of family medicine sub-Is at nonresidency sites (P=.48) or having an advanced ambulatory rotation requirement (P=.16).

Conclusions: A sub-I is a way to further expose students to family medicine, and increasing sub-I positions at residency programs may influence the number who pursue the specialty. Creation of a standardized sub-I curriculum presents an opportunity to enhance a critical educational experience in family medicine.

Because subinternships (sub-Is) are integral to the final year of medical school, an Alliance for Clinical Education panel has recommended the development of specialty-specific curricula for all sub-Is during the fourth year.1 Specialty stakeholders have created sub-I guidelines for internal medicine and pediatrics.2,3 However, a standardized family medicine sub-I curriculum has not been developed, and little is known about the current nature of family medicine sub-Is.

During a sub-I, students take on a more advanced role in patient care. Activities can include rounding on a larger volume of patients, creating an assessment and plan, writing progress notes, calling consults, taking night/weekend calls, entering orders/prescriptions, participating in patient handoffs, and communicating with patients and families. While sub-Is may include OSCE-type assessments, directly observed clinical activities, or written/didactic assignments, family medicine sub-I requirements are assumed to vary across institutions.

Multiple potential benefits exist for a standardized family medicine sub-I curriculum. For medical schools, the family medicine sub-I provides an opportunity to assess preparedness for residency, and commonly fulfills a graduation requirement.6 For students, a sub-I helps to confirm interest in the field to provide residency recommendation letters, and helps them prepare for internship.5 For the specialty of family medicine, sub-Is could assist in reaching the American Academy of Family Physicians’ target of 25 by 2030—that 25% of medical graduates will match into family medicine by 2030.4

In this study we investigated how sub-Is exist within medical school curricula, the settings in which family medicine sub-Is take place, how they may impact match rates, and the utility of a standardized family medicine sub-I curriculum.

We collected data as part of the 2019 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey that was mailed to 142 US and Canadian family medicine clerkship directors between June 19, 2019 and August 2, 2019.7 Nonrespondents received four weekly follow-ups and a final request before the survey closed. The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Survey Questions

Clerkship directors answered demographic and organizational questions that are part of every CERA survey,8 including percentage of medical school graduates that matched into family medicine in 2019. We added general sub-I questions and questions about family medicine sub-Is affiliated with the respondent’s school (ie, whether sub-Is are a graduation requirement, the number of family medicine sub-I opportunities at residency and nonresidency sites, composition of inpatient/outpatient time); current use of STFM National Clerkship Curriculum (NCC); whether a standardized sub-I curriculum would be used; and whether competency-based assessment tools would be desired for evaluation. Responses were yes/no, numerical, or based on a 5-point Likert-scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree). Sub-Is were defined broadly as “an advanced clinical rotation offered in the final phase of medical school, also known as acting-internship or AI.”

Analyses

We conducted data analysis using R version 3.6.1, and we recoded responses and completed bivariate analyses for all research questions. We used either Fisher exact test or a Mann-Whitney U test to calculate the statistical significance α=0.05) for all questions, which are found in Tables 1-4.

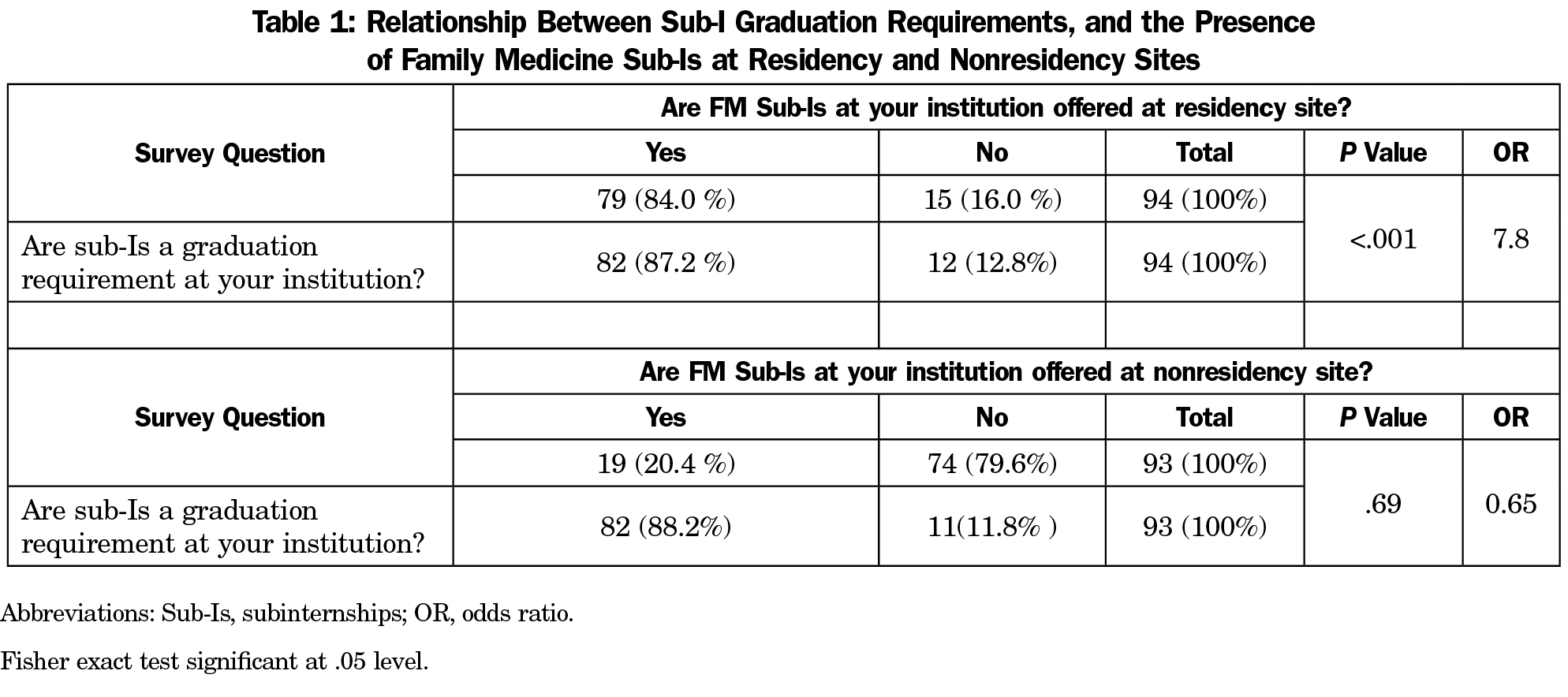

Of 142 clerkship directors, 71.1% responded to at least some survey questions. The majority (84.0%) stated that a sub-I, not restricted to family medicine, was a graduation requirement for their medical school. Schools with a sub-I graduation requirement were more likely to have a family medicine sub-I, with the majority occurring at residency sites (Table 1).

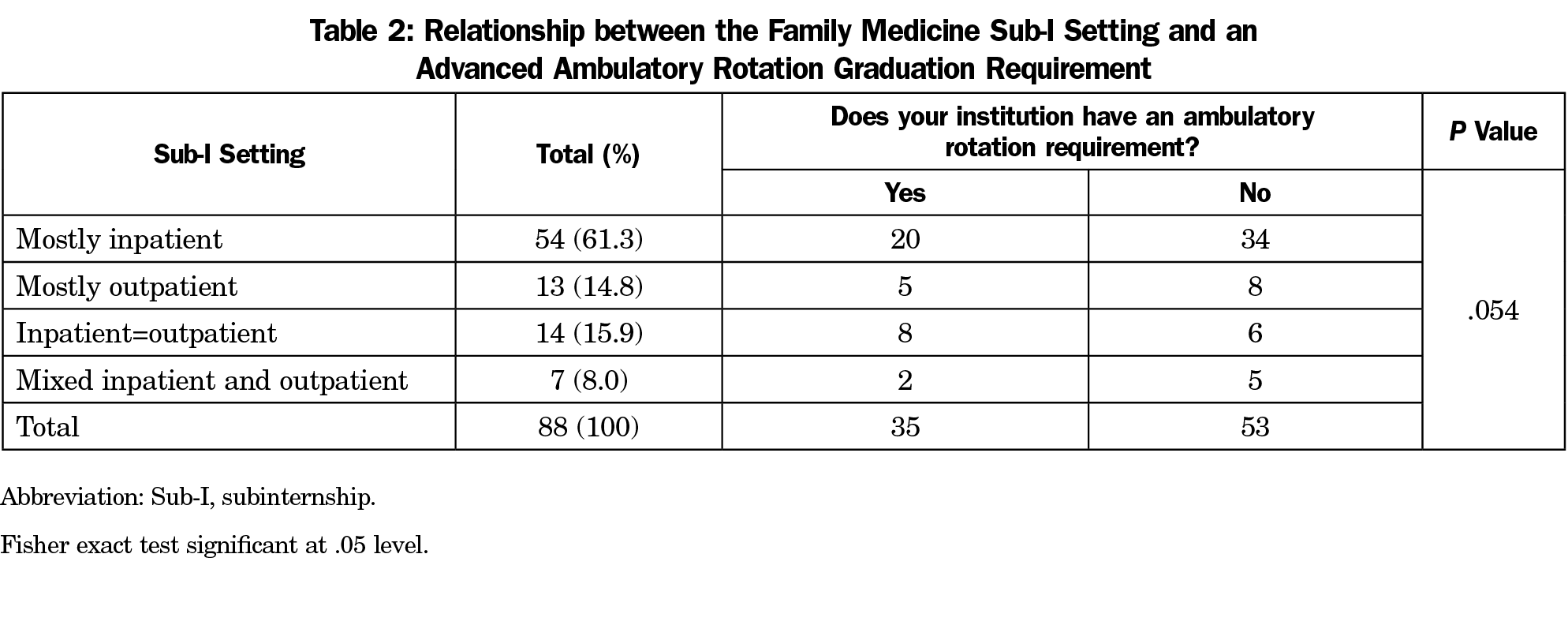

Although 38.3% reported an advanced ambulatory rotation requirement, this requirement was not associated with the setting of a school’s family medicine sub-I (Table 2). Most schools (61.4%) had primarily inpatient family medicine sub-Is; fewer (14.8%) reported primarily outpatient sub-Is, while the remaining schools (8.0%) had a mix of inpatient and outpatient.

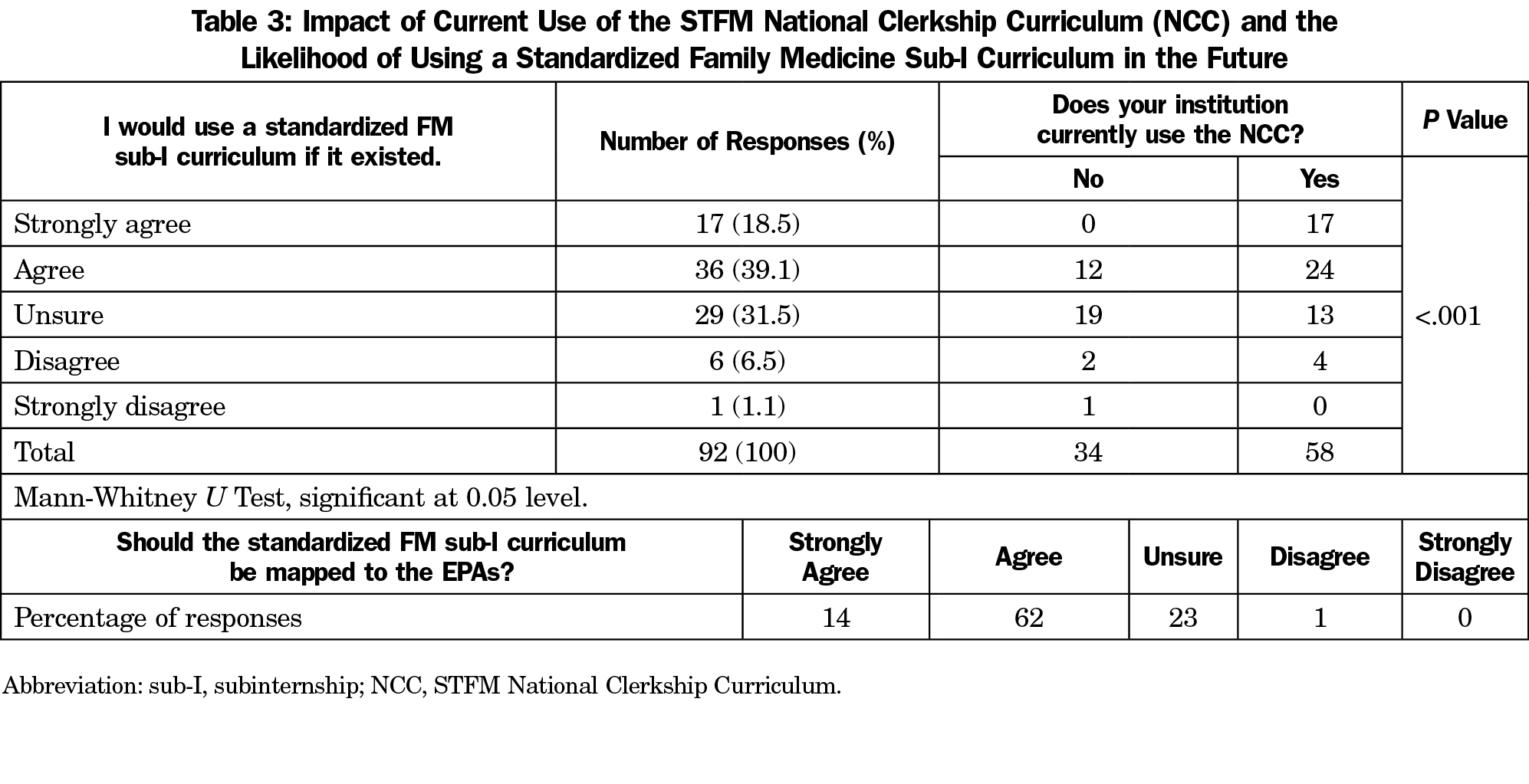

Only 63.0% of clerkship directors currently use the STFM NCC in their third-year family medicine clerkship, and doing so was associated with interest in using a standardized sub-I curriculum (Table 3).

Higher match rates in family medicine (Table 4) were positively associated with a sub-I requirement and with having a family medicine sub-I at a residency site (P<.001).

Similar to previous research, we found that most medical schools have a sub-I requirement.6 While an advanced ambulatory care rotation exposes students to outpatient care practiced by family physicians, requiring this course was not associated with students pursuing family medicine. With this finding and because match rates in family medicine were positively associated with any sub-I requirement, having more students complete a specific, named family medicine sub-I rotation may increase the number of students who pursue the specialty.

Furthermore, offering the family medicine sub-I at a residency site was associated with more students pursuing family medicine. This may be because residencies provide teaching environments where students are active team members and an exposure to role models close to their stage of training. As sub-Is at nonresidency sites were not related to entry into family medicine, an important avenue to work toward the AAFP’s 25 x 2030 goal may be to increase sub-Is affiliated with residency programs.

We found that the family medicine sub-I is variable in its setting, though more than half are primarily inpatient. Over half of family medicine clerkship directors reported they would use a standardized family medicine sub-I curriculum, and more than two-thirds reported support for a competency framework, such as the AAMC’s Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs).10 A competency-based, standardized sub-I curriculum would serve as a bridge between undergraduate medical education and the ACGME residency milestones.11

This study was limited by not including schools without family medicine clerkships—which likely have lower family medicine match rates, no family medicine sub-I, and less familiarity with the STFM NCC. Secondly, data accuracy may have been impacted by the assumption that clerkship directors are knowledgeable about their institution’s sub-Is, or would seek out this information.

Despite these limitations, this study provided essential background information about the family medicine sub-I, a topic that has not been widely studied. These results will inform next steps in the creation of a standardized family medicine sub-I curriculum, a product that has potential to enhance a critical education experience in family medicine.

References

- Reddy ST, Chao J, Carter JL, et al. Alliance for clinical education perspective paper: recommendations for redesigning the “final year” of medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26(4):420-427. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2014.945027

- Vu TR, Angus SV, Aronowitz PB, et al; CDIM-APDIM Committee on Transitions to Internship (CACTI) Group. The Internal Medicine Subinternship—Now More Important than Ever: A Joint CDIM-APDIM Position Paper. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1369-1375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3261-2

- The Council on Medical Student Education in Pediatrics and Association of Pediatric Program Directors. Pediatric Subinternship Curriculum. 2009. https://media.comsep.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/30172802/COMSEP-APPDF.pdf. Accessed Jan 30, 2019.

- Porter S. AAFP Hosts Launch of 25 x 2030 Student Choice Collaborative. 2018; https://www.aafp.org/news/education-professional-development/20180905twentyfiveby2030.html. Accessed Jan 30, 2019.

- Pereira AG, Harrell HE, Weissman A, Smith CD, Dupras D, Kane GC. Important skills for internship and the fourth-year medical school courses to acquire them: a national survey of internal medicine residents. Acad Med. 2016;91(6):821-826. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001134

- Elnicki DM, Gallagher S, Willett L, et al; Clerkship Directors in Internal Medicine Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine Committee on Transition to Internship. Course offerings in the fourth year of medical school: how U.S. medical schools are preparing students for internship. Acad Med. 2015;90(10):1324-1330. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000796

- Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW. Creating a centralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257-260. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2228

- Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance. Recurring Demographic Questions. https://www.stfm.org/publicationsresearch/cera/howtoapply/recurringquestions/#tab-7876. Accessed November 1, 2019.

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. National Clerkship Curriculum. 2018; 2nd edition. https://www.stfm.org/media/1828/ncc_2018edition.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed November 1, 2019.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. The Core Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) for Entering Residency. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/medical-education/cbme/core-epas. Accessed November 1, 2019.

- The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Board of Family Medicine. The Family Medicine Milestone Project. 2015; https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/FamilyMedicineMilestones.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed November 1, 2019.

There are no comments for this article.