Background and Objectives: Rates of injection drug use and associated medical complications have increased, yet engagement of persons who inject drugs (PWID) in primary care is limited, with significant barriers to care. Family physicians play an important role in caring for PWID, but residency training is limited. This study aimed to assess role responsibility, self-efficacy, and attitudes of family medicine residents in caring for PWID.

Methods: Using a cross sectional design, family medicine residents in 2018 at three different programs completed Likert and open-ended survey questions assessing role responsibility, self-efficacy, and attitudes in caring for PWID.

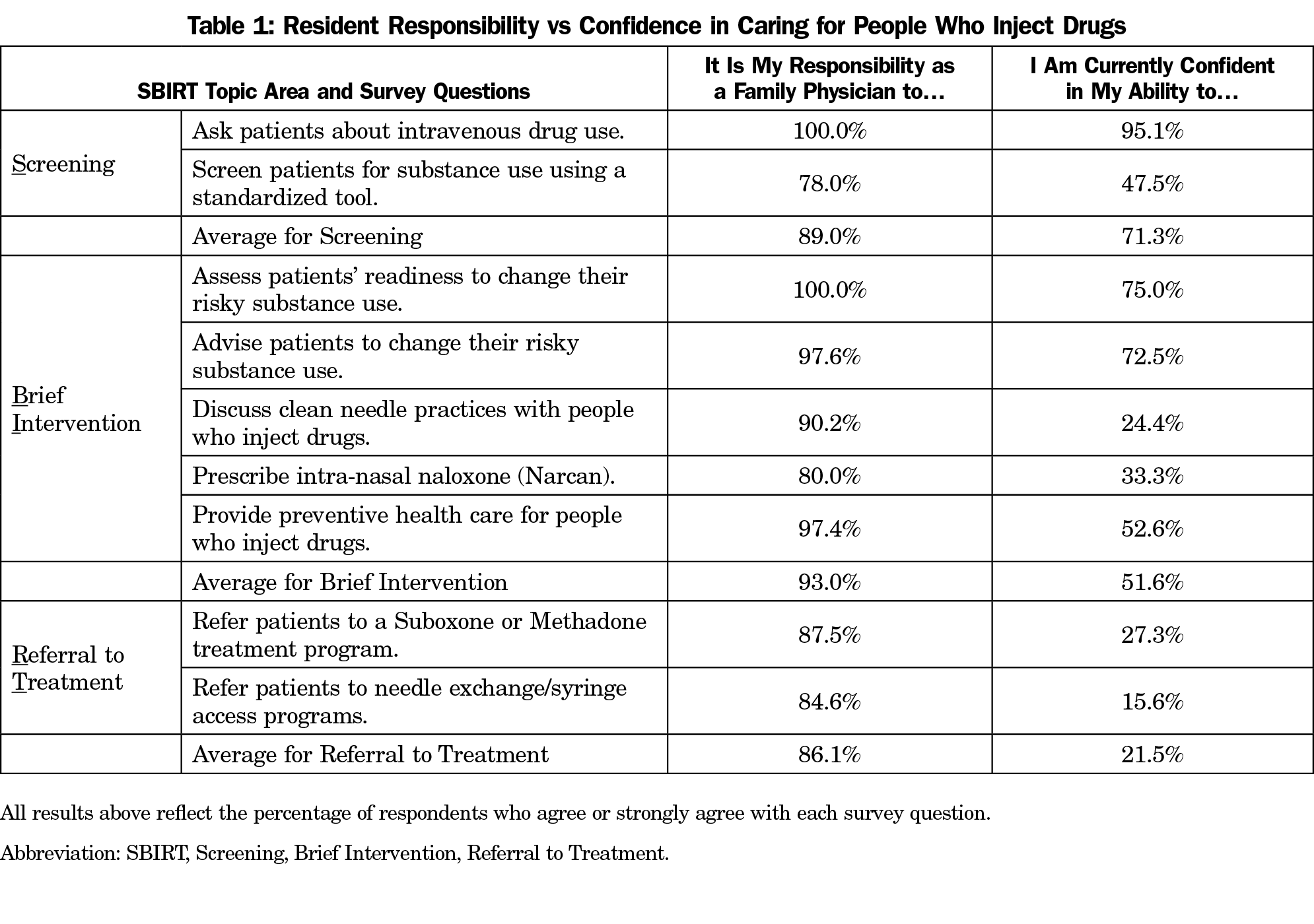

Results: Fifty-five percent (41/76) of residents completed surveys. Residents consistently agreed it is their responsibility to provide comprehensive care for PWID, while being less confident in key elements of screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT). The largest gap between responsibility and confidence was in referral to treatment. Resident confidence was lowest for harm reduction strategies: discussing clean needle practices, prescribing naloxone and referral to medication-assisted treatment or needle exchange programs. Less than 60% of residents agreed they are able to work with or understand PWID.

Conclusions: This study identifies gaps between provider responsibility and current graduate medical education training. We identified training that increases screening, harm reduction practices, and referrals to community resources as needs. This baseline assessment of family medicine residents can be used to develop educational interventions to meet regional and national health needs for harm reduction for PWID and workforce development.

In the United States, over 750,000 people now actively inject drugs,1,2 with rates of heroin use nearly quintupling over the last decade. Despite numerous health issues for people who inject drugs (PWID),3 engagement with primary health care is disproportionately low4 and primary care providers feel unprepared5 and have lower regard for patients with substance use disorders.6 Numerous physician barriers to addiction management in a primary care setting have been found, such as limited addiction training, limited use of Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT),7 need for greater behavioral health integration,8 lower professional satisfaction,9 implicit bias,10,11 and a lack of confidence in treatment efficacy.12

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration endorses SBIRT and strengthening addiction-related health education for physicians.13 Harm reduction strategies seek to reduce stigma and the negative consequences of substance use. However, only 46% of family medicine clerkship directors are familiar with SBIRT,14 and only 28.6% of family medicine residency program directors reported a required addiction medicine curriculum.15 Additionally, among internal medicine, family medicine, and psychiatry residency programs in the United States, only 36% of program directors reported providing training in office-based opioid treatment, and 23% provide buprenorphine waiver training.16 With limited training, 7% of graduates reported providing buprenorphine treatment in the 2016 National Family Medicine Graduate Survey.17

Prior research has demonstrated that implementation of SBIRT in residency training is feasible and acceptable,18–20 but there remain few evaluations of educational needs, particularly with a focus on self-efficacy, at the graduate level.21,22 Self-efficacy, defined as the belief in one’s capacity to accomplish a task, is particularly relevant as we go beyond knowledge and study effective behavior change in residency. Further, past studies were not specific to PWID, a group that faces more stigma and health disparities than those with other substance use disorders. In addition, prior surveys assessing role responsibility, self-efficacy, and attitudes of emergency medicine residents23 and practicing primary care providers7,24 found low rates of implementation of SBIRT for alcohol and substance abuse.

This study aimed to assess role responsibility, self-efficacy, and attitudes of family medicine residents in caring for PWID, that can be used to develop educational interventions to meet regional and national health needs for workforce development.

This study used a cross-sectional design. Prior to attending didactic teaching sessions on SBIRT and working with PWID at three residency programs in 2018, all participants completed questionnaires with quantitative questions using 5-point, Likert scale questions (responses: strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, strongly agree) and open-ended responses. For analysis, responses of agree or strongly agree were grouped and compared to all other responses as a group. In addition, respondents self-reported gender (male/female) and year of training. The survey questions were adapted from previously published studies related to resident and primary care professionals’ role responsibility, self-efficacy, and attitudes regarding SBIRT for substance abuse.7,23,24 Chosen questions focused on comparing resident responsibility and their confidence in three domains: screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. We collected and managed data using RedCap (Research Electronic Data Capture)25 at Penn State Hershey. We grouped open-ended responses and coded and analyzed emergent themes using NVivo (Version 12, QSR; performed by author J.S.). We obtained institutional review board approval prior to collection of surveys, and all participants provided verbal consent to participate.

In total, 41/76 (55%) of residents (17 from Penn State Hershey, 10 from University of Maryland, and 14 from Georgetown University) completed surveys. The overall sample was 66% female and included residents who were in year 1 (32%), year 2 (34%), and year 3 (34%). The proportion of participants who agreed with each SBIRT-related survey question are presented in Table 1. When comparing role responsibility and confidence, more than 85% of residents agreed that it is their responsibility to provide comprehensive care for PWID, however their confidence in completing these activities in practice varied from 71% to 21.5%. Resident confidence did not vary based on age, training year, or gender. Residents felt most confident in screening for intravenous drug use and assessing and advising change behaviors, but expressed much less confidence in brief interventions and referral to treatment. The largest gap (64%) between role responsibility and ability was in referral to treatment. Resident confidence was lowest (<35%) for harm reduction strategies, such as discussing clean needle practices, prescribing naloxone, and referral to medication-assisted treatment programs or needle exchange programs.

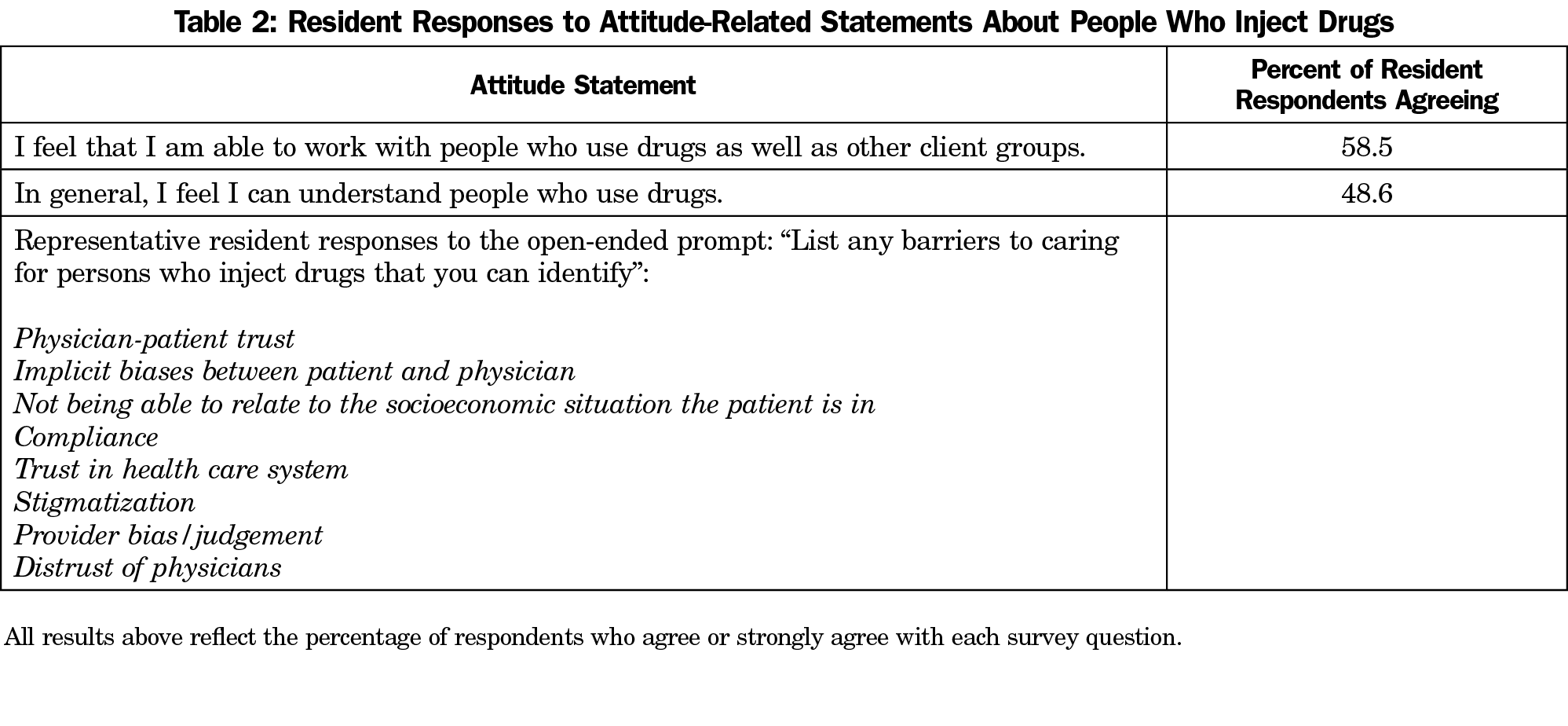

Attitudes toward persons who use drugs are presented in Table 2. Less than 60% of residents agreed they are able to work with or understand PWID. Residents listed the highest frequency of barriers to care in aspects of the doctor-patient relationship (eg, trust, relatability, compliance, stigma) that they perceived to be barriers for both physicians and patients.

This survey of medical residents highlights a gap between what residents perceive to be their role responsibility as physicians and their self-efficacy to care for PWID. While respondents expressed confidence in broaching the topic of injection drug use, they were less confident in formal assessment using established screening tools. Like the participants in the Seale, et al study20 that assessed alcohol screening, our study demonstrates a low baseline rate of screening in residency clinics, highlighting the need for additional training and systems-based interventions. While Seale et al did not observe an increase in the use of medications nor referral to treatment, our study highlights the largest gap in resident confidence in referral to treatment, which likely reflects a combination of limited medical training, a fractured health care system, need for patients to self-refer, stigma regarding addiction, limited access to evidence-based community addiction services, and the disconnect between medical training and community drug and alcohol services.

Respondents were more confident in advising patients to change their risky substance use, indicating greater confidence in motivational interviewing skills (a focus of the National SBIRT Residency Training Project22), and a lack of knowledge regarding harm reduction strategies, which can reduce morbidity and mortality and the sequelae of injection drug use. Residency education should continue to address the difficult nature of the provider-patient relationship for PWID that was identified in open-ended answers. Regardless of training year, respondents consistently identified that trust may be difficult to build in these patient-provider relationships. These findings emphasize the importance of additional exposure to the lived experience of PWID and exploration of stigma and bias in curricular design.

This study is limited by a small sample size, potential homogeneity of the residency programs, and potential response bias. The programs surveyed were near major East Coast cities that have experienced high morbidity and mortality from the current opioid epidemic, and results may differ in more rural areas. Additionally, the confidence documented by respondents may not fully reflect actual practice patterns. However, we believe that the results from this study can provide important insights into development of future residency training.

Overall, this study highlights the urgent need for innovative educational interventions to help graduate medical trainees to address the gap between perceived provider responsibility and their current skill sets. Given the magnitude of the current opiate epidemic, family physicians will increasingly encounter PWID and need to appropriately screen, intervene, and refer to treatment. As such, focused experiential residency training in harm reduction, knowledge, and integration with local resources, referral to treatment, and addressing bias will be critical in addressing the needs of PWID.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Arthur Berg, PhD, for statistical support for the project; and Susan Veldheer, DEd, RD, for editorial assistance.

Prior Presentations: This work was presented in 2019 in the following settings:

- Poster at the EdVenture conference in Hershey, Pennsylvania

- Poster at the Family Medicine Educational Consortium conference in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

- Oral presentation at the Penn State Addiction Symposium in Hershey, Pennsylvania

References

- Lansky A, Finlayson T, Johnson C, et al. Estimating the number of persons who inject drugs in the United States by meta-analysis to calculate national rates of HIV and hepatitis C virus infections. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97596.

- Jones CM, Logan J, Gladden RM, Bohm MK. Vital signs: demographic and substance use trends among heroin users - United States, 2002-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(26):719-725.

- Degenhardt L, Whiteford HA, Ferrari AJ, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to illicit drug use and dependence: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1564-1574. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61530-5

- Chitwood DD, McBride DC, French MT, Comerford M. Health care need and utilization: a preliminary comparison of injection drug users, other illicit drug users, and nonusers. Subst Use Misuse. 34(4-5):727-746. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826089909037240

- Wakeman SE, Pham-Kanter G, Donelan K. Attitudes, practices, and preparedness to care for patients with substance use disorder: results from a survey of general internists. Subst Abus. 2016;37(4):635-641. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2016.1187240

- van Boekel LC, Brouwers EPM, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HFL. Healthcare professionals’ regard towards working with patients with substance use disorders: comparison of primary care, general psychiatry and specialist addiction services. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;134(1):92-98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.09.012

- Harris BR, Yu J. Attitudes, perceptions and practice of alcohol and drug screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment: a case study of New York State primary care physicians and non-physician providers. Public Health. 2016;139:70-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.05.007

- Rahm AK, Boggs JM, Martin C, et al. Facilitators and barriers to implementing Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) in primary care in integrated health care settings. Subst Abus. 2015;36(3):281-288. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2014.951140

- Saitz R, Friedmann PD, Sullivan LM, et al. Professional satisfaction experienced when caring for substance-abusing patients: faculty and resident physician perspectives. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(5):373-376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-002-0043-4

- Press KR, Zornberg GZ, Geller G, Carrese J, Fingerhood MI. What patients with addiction disorders need from their primary care physicians: A qualitative study. Subst Abus. 2016;37(2):349-355. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2015.1080785

- van Boekel LC, Brouwers EPM, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HFL. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):23-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018

- Johnson TP, Booth AL, Johnson P. Physician beliefs about substance misuse and its treatment: findings from a U.S. survey of primary care practitioners. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40(8):1071-1084. https://doi.org/10.1081/JA-200030800 PMID:16040369

- Samhsa. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Strategic Plan FY2019-FY2023.; 2019. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/samhsa_strategic_plan_fy19-fy23_final-508.pdf. Accessed May 1, 2019.

- Carlin-Menter SM, Malouin RA, WinklerPrins V, Danzo A, Blondell R. Training family medicine clerkship students in Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment for substance use disorders: a CERA study. Fam Med. 2016;48(8):457-468.

- Tong S, Sabo R, Aycock R, et al. Assessment of addiction medicine training in family medicine residency programs: a CERA study. Fam Med. 2017;49(7):537-543.

- Tesema L, Marshall J, Hathaway R, et al. Training in office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine in US residency programs: A national survey of residency program directors. Subst Abus. 2018;39(4):434-440. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2018.1449047

- Tong ST, Hochheimer CJ, Peterson LE, Krist AH. Buprenorphine provision by early career family physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(5):443-446. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2261

- Tetrault JM, Green ML, Martino S, et al. Developing and implementing a multispecialty graduate medical education curriculum on Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT). Subst Abus. 2012;33(2):168-181. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2011.640220

- Whittle AE, Buckelew SM, Satterfield JM, Lum PJ, O’Sullivan P. Addressing adolescent substance use: teaching Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) and Motivational Interviewing (MI) to residents. Subst Abus. 2015;36(3):325-331. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2014.965292

- Seale JP, Johnson JA, Clark DC, et al. A Multisite initiative to increase the use of alcohol screening and brief intervention through resident training and clinic systems changes. Acad Med. 2015;90(12):1707-1712. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000846

- Agley J, Gassman RA, DeSalle M, Vannerson J, Carlson J, Crabb D. Screening, Brief Intervention, Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), and Motivational Interviewing for PGY-1 Medical Residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(4):765-769. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-14-00288.1

- Pringle JL, Kowalchuk A, Meyers JA, Seale JP. Equipping residents to address alcohol and drug abuse: the national SBIRT residency training project. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(1):58-63. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-11-00019.1

- D’Onofrio G, Nadel ES, Degutis LC, et al. Improving emergency medicine residents’ approach to patients with alcohol problems: a controlled educational trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;40(1):50-62. https://doi.org/10.1067/mem.2002.123693

- Harris BR, Shaw BA, Sherman BR, Lawson HA. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for adolescents: attitudes, perceptions, and practice of New York school-based health center providers. Subst Abus. 2016;37(1):161-167. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2015.1015703

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

There are no comments for this article.