Background and Objectives: According to a previous study, obstetric deliveries may be protective against burnout for family physicians. Analyses of interviews conducted during a larger qualitative study about the experiences of early-career family physicians who intended to include obstetric deliveries in their practice revealed that many interviewees discussed burnout. This study aimed to understand the relationship between practicing obstetrics and burnout based on an analysis of these emerging data on burnout.

Methods: We conducted semistructured interviews with physicians who graduated from family medicine residency programs in the United States between 2013 and 2016. We applied an immersion-crystallization approach to analyze transcribed interviews.

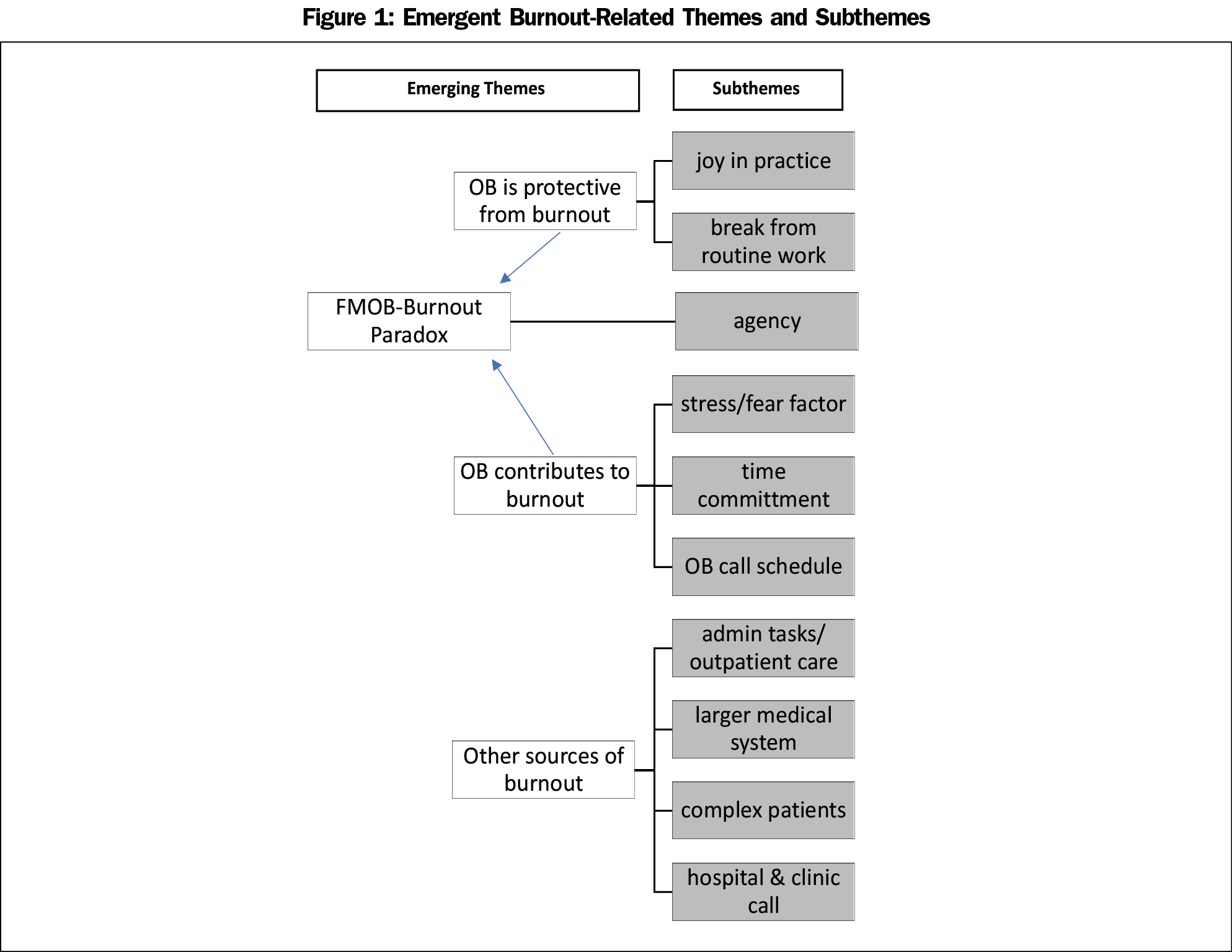

Results: Fifty-six early-career family physicians participated in interviews. Burnout was an emerging theme. Physicians described how practicing obstetrics can protect from burnout (eg, brings joy to practice, diversity in practice), how it can contribute to burnout (eg, time demands, increased stress), how it can do both simultaneously and the importance of professional agency (ie, the capacity to make own free choices), and other sources of burnout (eg, administrative tasks, complex patients).

Conclusions: This study identifies a family medicine-obstetric paradox wherein obstetrics can simultaneously protect from and contribute to burnout for family physicians. Professional agency may partially explain this paradox.

Physician burnout is a significant issue in all medical specialties. A 2011 national study found that rates of burnout are higher among physicians than other US workers,1 prompting further studies focused on physician burnout.2-4 Physician and other health care worker burnout is particularly concerning as it may be associated with worse patient outcomes.5 Recognizing the association between burnout and poor patient outcomes and increased costs of care, Bodenheimer et al suggested adding a fourth aim to the Triple Aim.6 The Triple Aim was created in 2008 with the goal of optimizing health system performance including improving the patient experience, focusing on patient health, and decreasing costs.7 Noting that these could not be accomplished with a significant proportion of the health care workforce experiencing burnout, the Quadruple Aim includes improving the work life of health care providers. As a specialty experiencing some of the highest rates of burnout (48%), family physicians (FPs) led the call for the Quadruple Aim.6,8

Multiple studies have attempted to understand the contributing factors to burnout in family medicine.9-12 One study of over 1,600 FPs examined the association between various practice characteristics and burnout. Practicing obstetrics (OB) was found to be independently and statistically significantly associated with lower levels of physician burnout, raising questions about how and why practicing OB might impact burnout among FPs.13

Practicing OB was once fairly common for family physicians, with 46% including OB in their practice in 1978.14 Over the past 4 decades, however, the number of FPs practicing OB has steadily declined with only 8% including OB in 2016.15 Recent work has aimed to support family physicians including OB in their practice with an understanding that this may be critical in the setting of a continual decline of the overall OB workforce.18 While only 8% of current family physicians include OB in their practice, nearly 22% of recent graduates intend to include OB in their practice.19

While conducting a qualitative study of recent family medicine graduates to better understand the motivating factors and barriers faced by FPs who want to include obstetric deliveries in their practice, 20,21 we found that almost all participants discussed the concept of burnout related to practicing OB. We aimed to explain how and why practicing OB might be associated with lower levels of burnout13 by examining the ways in which FPs discussed the relationship between practicing OB and burnout.

One strength of qualitative research is that unexpected findings that go beyond the original research question often emerge; during interviews for a study involving early-career family physicians, most participants discussed the concept of burnout, by their own definition. This paper presents an examination of these emerging qualitative data to help explain the relationship between practicing OB (defined as delivering babies, though it may also include providing other aspects of maternity care) and burnout.

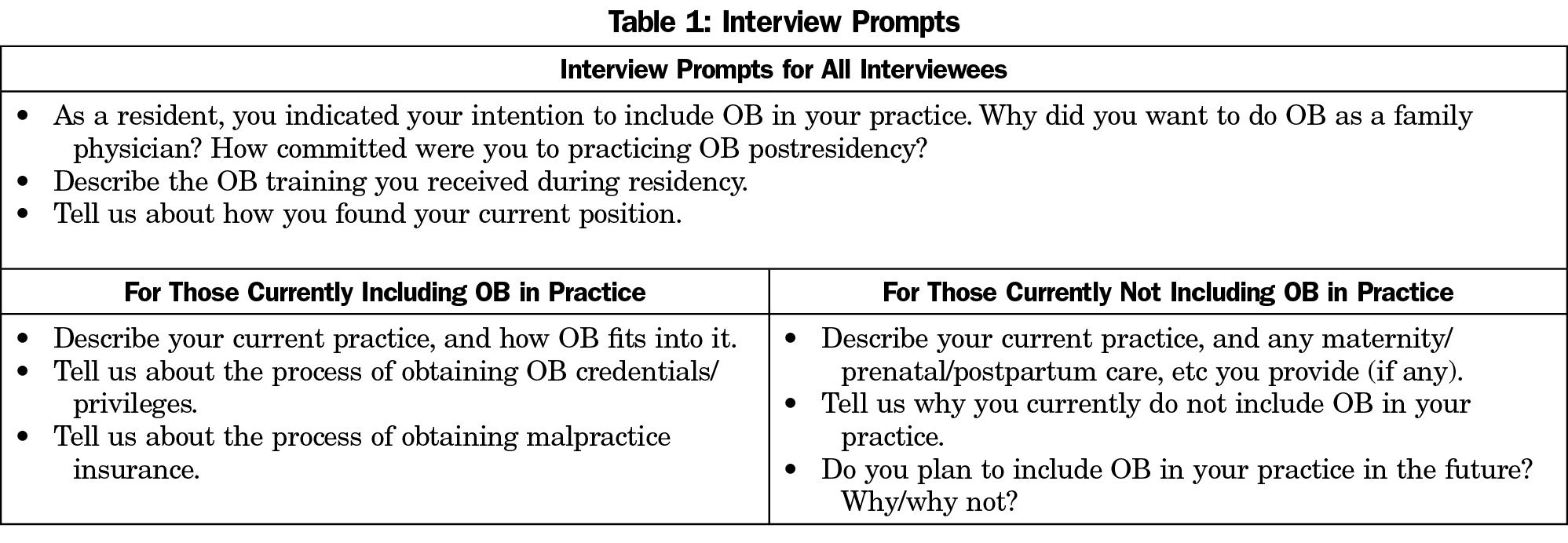

As reported in detail elsewhere,20,21 in 2017, we conducted semistructured telephone interviews with 56 recent family medicine graduates to understand intention to include OB in their practice. We used data from the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) to identify and recruit all FPs who graduated from residency between 2014 and 2016 and who, upon registering for their Board certification exam, indicated that they planned to include obstetric deliveries in their practice. These graduates were sent a five-question survey via email about their current practice. The final survey question asked respondents if they would participate in an interview. From the list of the 565 physicians who agreed to participate in an interview (56% of 1,016 survey respondents), we purposefully identified a diverse and representative sample of physicians in terms of volume of obstetrical deliveries, or reason for not performing deliveries, as well as geographic variation. Participants signed informed consent forms, and trained qualitative researchers conducted 45 to 60-minute telephone interviews that were recorded and professionally transcribed. These semistructured interviews followed a series of question prompts (Table 1). The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved this study.

We used an immersion-crystallization analytic approach that involved cycles of concentrated textual review to apply a priori codes defined in alignment with the interview guide, and to generate and define emergent codes. This iterative process was completed with three coders, two of whom independently coded each interview transcript.22,23 During these analyses, the concept of burnout emerged as a theme. We further analyzed the interview segments concerning burnout, using the same iterative coding process to identify themes pertaining to burnout and practicing OB and to add another level of interpretation of the rich data.

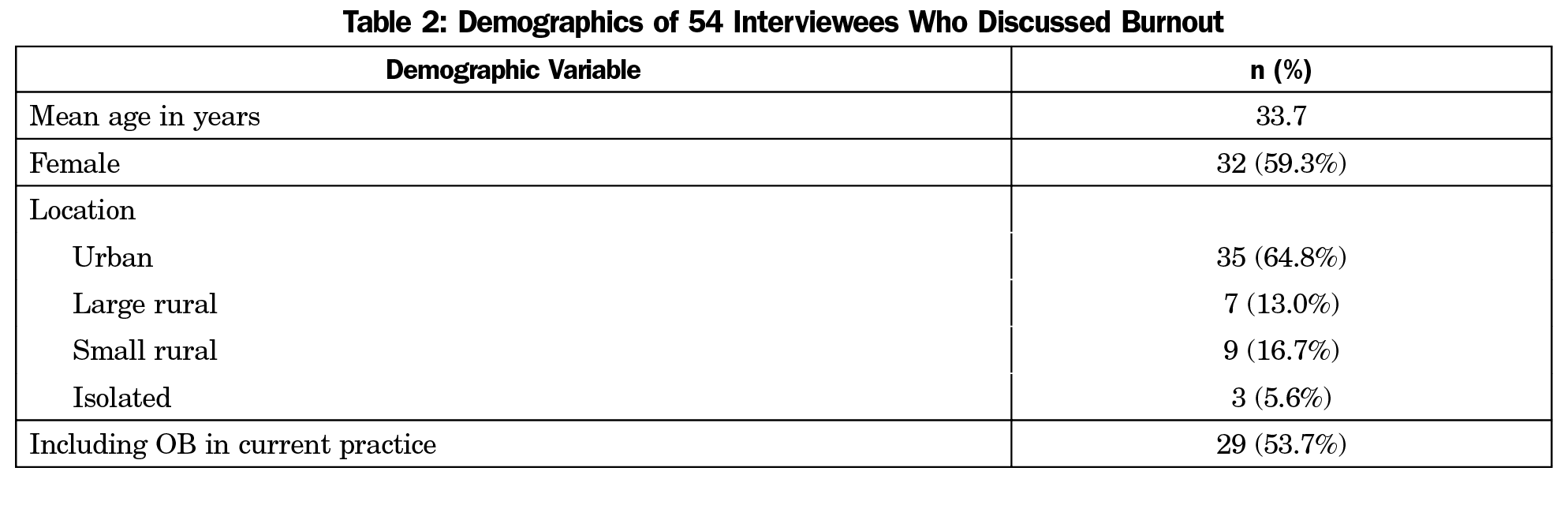

We identified the theme of burnout in 54 of the 56 interviews with early-career FPs. Of the 54 interviewees who discussed burnout, 29 (53.7%) were currently including obstetric deliveries in their practice. See Table 2 for other characteristics of the interviewees. Four main burnout-related themes emerged (Figure 1) and are described below.

OB Is Protective Against Burnout

Interviewees described the ways in which including OB in practice protects them from feeling burned out. They provided examples of mechanisms through which this happens, including feelings of joy experienced from practicing OB and the diversity OB brings to their clinical practice.

For me personally, coming back to my story of why I chose family medicine and my love of OB and delivering babies, it really brings a lot of joy to my practice as well, and prevents burnout in that sense that I really love taking care of prenatal patients. I like having a young practice. I like doing well-child…and prenatal care. Typically, those babies become my patients, and so, then I’ve got the whole family. −Female physician performing deliveries

Interviewees also noted that practicing obstetrics created an opportunity for time away from routine outpatient and administrative tasks.

I think because I have that variety with seeing kids, seeing prenatal visits, doing deliveries, like, there’s always something different to look forward to, whereas if I were just in the office all day every day, trying to turn out patient, turn out notes, click boxes, and sign things, and whatever, I don’t think I would last this long. −Female physician performing deliveries

OB Contributes to Burnout

Interviewees who described how OB contributes to their experience of burnout focused on two broad mechanisms: stress/fear and time commitment. A few interviewees described experiences of poor obstetric outcomes that led to concern and increased feelings of stress about future OB experiences.

I’ve had some burnout issues in just my three short years in practice. And I think some of them have been related to the practice of obstetrics for me personally, that had to do with a medical error that occurred. And so, like I said the fear factor of OB I think does play a psychologic role. Because there are complications that can happen, that can be very serious. −Female physician performing deliveries

They also indicated that time spent on OB call, and therefore time spent away from their personal lives, can contribute to feelings of burnout.

I would basically have 6 days off a month and then be on call for the other 24 days around the clock for C-section. And we lived in a really rural community. There was no Walmart, no Target, nothing like that, so the only time that I could ever go do any of that kind of stuff was whenever I was completely off because those places weren’t within my 15-mile radius of the hospital.… And so I–they knew I was burning out. −Female physician performing deliveries

Some interviewees said that OB was only one factor contributing to feelings of burnout, or indicated their desire to continue to practice OB but under a better call schedule or call coverage environment.

I did definitely feel burned out those first 2 years. I think OB was definitely a factor. I don’t think it was 100% because of OB that I was burned out. We also have a huge physician shortage in rural America. We have a lot of patients to see and not enough doctors. It would be busy in the clinic and then if I got pulled away to do a delivery, and then be stuck there all night not get home to see my kiddos or husband or even take a shower before going to the clinic the next day…. It [OB] was a part of it. I don’t think it would be the only thing that would be causing burnout. −Female physician not performing deliveries

Family Medicine OB Burnout Paradox

While physicians described the ways in which practicing OB might either prevent or contribute to burnout, many discussed both, directly noting that OB simultaneously protects from and contributes to burnout.

I think in some ways that [OB] contributes, [and] in some ways that [OB] protects. I think it’s hard to say. But I think it’s definitely usually a really fun part of my job, but definitely sometimes can be really stressful. (Female physician performing deliveries)

In most of these descriptions, physicians expressed a temporal aspect, ie, the ways in which obstetrics contributes to burnout are temporary and confined to short points in time, while the protective nature is ongoing.

If we weren’t doing OB, I wouldn’t have any call. I could leave every weekend because we don’t do in-patient here.… Even if we’re not busy, I still have to be within 30 minutes of the hospital. There’s still just that constant restriction on what you can do in making plans and stuff. So, it does add to it [burnout], but I also think if I was doing just out-patient all the time, then I would probably be bored …or … I wouldn’t enjoy it as much. So, I think OB can contribute to it, but I think there’s also a lot of benefit to it that I think makes it worth it. −Male physician performing deliveries

Interviewees sometimes expressed this paradox through the concept of agency, defined as the capacity for the individual to act independently, make their own free choices, or exert power.24 Physicians who actively chose to practice OB despite added stress and uncertainty, time on call, and missing out on family events, were protected from burnout. On the other hand, physicians who indicated that they felt a lack of control or autonomy over larger organizational and systems-level issues, including required administrative tasks and paperwork, described how this lack of agency contributed to feelings of burnout. Similarly, some physicians emphasized that a lack of control over their time and schedules caused or exacerbated their feelings of burnout. Some described the need to actively and consistently try to maintain an acceptable work-life balance.

I kind of look at burnout as the sense of the loss of control. When you feel like you don’t have control over your schedule or what you’re doing with your patients, then you really start to feel like a cog in the machine. But I actually felt like when I had my OB patients I had more control…. −Male physican not performing deliveries

Other Sources of Burnout

Physicians who included OB in their practice often pointed out that the sources of their burnout were not directly related to the practice of OB. For example, the daily tedium of administrative tasks, the lack of diversity in daily out-patient care, stress of caring for complex patients, and the inefficiency or demands of the broader medical system were all mentioned as the source of burnout, as opposed to practicing OB.

But, at least for me right now, burnout is – I think it’s a significant risk in [the current] generation of doctors, and so I think it has more to do with the system that we’re working in, and not to do with whether or not we’re doing OB or call or whatever. I think it’s a lot of—for me anyway—frustration, as a lot of things seem either pointless or not helpful, or you’re trying your best to help a patient, and the system is really working against you and working against the patient. −Female physician performing deliveries

They discussed feeling burned out in other aspects of their work. Some mentioned that complex, non-OB, patients were a source of burnout.

In terms of my practice, my burnout comes more from my non-OB patients. It comes from my chronic pain, the opiate addiction, dealing with the social issues and the mental illness. That causes me a lot more frustration. −Male physician performing deliveries

They also discussed other call schedules such as clinic call or hospital inpatient call that contribute to burnout.

I think frankly, the thing that would contribute more to burnout… and will need to be addressed, is the hospital call, because I really, theoretically like the idea of being a full-spectrum family medicine doctor and doing hospital stuff. But once a week, like, going in all throughout the night to do admits is really, really tiring. −Female physician performing deliveries

This study begins to explain the previously reported finding that FPs practicing OB are less likely to report burnout.13 We identified a family medicine OB burnout paradox, wherein OB can be both protective from and contribute to feelings of burnout for the same individual FP. Considering previously published quantitative findings13 along with the qualitative data presented here, the protective aspects of including OB in practice may be stronger than those contributing to burnout. Further, these qualitative data suggest that despite the inherent uncertainty around delivering babies (as illustrated by the themes of fear factor and time), it is generally not OB practice itself that contributes to burnout. Rather, the structures around OB practice (call schedules, lack of adequate backup), as well as other unrelated patient and work environment factors, appear to contribute to feelings of burnout, and these could be addressed at the institutional level. This finding supports previous research that identified the work environment and tension between direct and indirect patient care work as contributing to burnout in family medicine.25

The family medicine OB paradox in family medicine might be elucidated by the concept of agency, in terms of both choice and a sense of control over their work. Many FPs emphasized that practicing OB is work they purposefully chose, even knowing that it can lead to more call and time away from family. Having a sense of control over their scope of practice may help to explain why some FPs feel OB is protective against burnout. Yet while agency can protect against burnout, it might also contribute to it, depending on how much agency a physician has over their schedule or over their decision to practice obstetrics in the first place. A lack or loss of control over other areas of family medicine might contribute to burnout, with or without a sense of control over OB practice in particular.

The previously published lower rates of burnout in FPs who practice OB might be explained in multiple ways.13 One possibility is that it is not that OB is protective of burnout, but that OB increases job satisfaction, especially for those FPs who were trained and committed to providing such care. Future research might explore the relationship between job satisfaction, scope of practice, and burnout. While practicing OB may be protective against burnout for FPs who originally intended to include OB in their practice, OB may not be protective for FPs who do not want to practice OB.

Physicians noted other factors, such as administrative tasks, as playing a larger role in feelings of burnout than OB practice, which is consistent with the current literature on burnout.2,12,26 Further, multiple FPs described OB as a means to get away from (at least temporarily) other sources of burnout, thus protecting against burnout. It is also possible that FPs practicing OB have a stronger tolerance for uncertainty or feel that the rewards from OB care mitigate or cancel out the problems of uncertainty. When work structures are designed to minimize uncertainty, at least in terms of schedule, time, and adequate backup, physicians may be less likely to feel that OB contributes to burnout.

A primary limitation of this study was the sample. First, from the full sample, only a self-selected group agreed to participate in an interview, leading to potential selection bias. Second, only recent graduates were interviewed. FPs who have been in practice longer may have different perspectives on the relationship between doing OB and burnout. Third, we interviewed only FPs who, upon residency graduation, intended to do OB in practice. FPs who did not intend to include OB in practice but now practice OB might have different experiences. Likewise, FPs who did not intend to include OB and who do not practice OB might have different experiences, personality traits, or characteristics that could help explain differences in burnout rates. Our study leaves us unable to know whether FPs who choose to practice OB are inherently different in terms of individual personality traits or resilience compared with those who do not.

Another limitation is that burnout was not explored systematically during the interviews as it was not an original research question. This may contribute to incomplete data as perhaps those interviewees experiencing burnout were more likely to discuss it in the interview. However, as almost all interviewees discussed burnout in some way, it is a justifiable emerging theme. In addition, because we did not measure burnout in our participants using validated instruments, and because burnout was an emerging theme in our data, we rely on physician’s own definitions of what burnout means to them and whether or not they have experienced burnout.

Efforts to identify what contributes to and protects from burnout may be critical in informing interventions to prevent burnout and thereby improve patient safety and work toward the Quadruple Aim.5,6 The findings reported here on the relationship between burnout and practicing OB as a family physician begin to provide insights into the relationship between burnout and scope of practice in family medicine for family physicians early in their career. Future studies can shed additional light on how scope of practice might influence physician satisfaction and wellness. Over 20% of new graduates intend to include obstetrics in their practice.19 FPs who want to practice OB should have access to adequate, quality training and be supported by the clinics, hospitals, and health systems in which they work, as this might protect those FPs from burnout.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest Statement: Dr Eden and Ms Brock are employed by the American Board of Family Medicine. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Balance in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023

- Rabatin J, Williams E, Baier Manwell L, Schwartz MD, Brown RL, Linzer M. Predictors and Outcomes of Burnout in Primary Care Physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(1):41-43. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150131915607799

- Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, et al. Prevalence of Burnout Among Physicians: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1131-1150. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.12777

- Burnout Among Health Professionals and Its Effect on Patient Safety. AHRQ Patient Safety Network. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/perspectives/perspective/190/burnout-among-health-professionals-and-its-effect-on-patient-safety. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-576. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1713

- Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759-769. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759

- Berg S. Physician burnout: which medical specialties feel the most stress. American Medical Association. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/physician-burnout-which-medical-specialties-feel-most-stress. Published January 21, 2020. Accessed July 10, 2019.

- Hansen A, Peterson LE, Fang B, Phillips RL Jr. Burnout in Young Family Physicians: Variation Across States. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(1):7-8. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2018.01.170269

- Blechter B, Jiang N, Cleland C, Berry C, Ogedegbe O, Shelley D. Correlates of Burnout in Small Independent Primary Care Practices in an Urban Setting. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(4):529-536. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2018.04.170360

- Puffer JC, Knight HC, O’Neill TR, et al. Prevalence of Burnout in Board Certified Family Physicians. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(2):125-126. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2017.02.160295

- Rassolian M, Peterson LE, Fang B, et al. Workplace Factors Associated With Burnout of Family Physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):1036-1038. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1391

- Weidner AKH, Phillips RL Jr, Fang B, Peterson LE. Burnout and Scope of Practice in New Family Physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):200-205. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2221

- Rosenblatt RA, Cherkin DC, Schneeweiss R, et al. The structure and content of family practice: current status and future trends. J Fam Pract. 1982;15(4):681-722.

- Barreto T, Peterson LE, Petterson S, Bazemore AW. Family Physicians Practicing High-Volume Obstetric Care Have Recently Dropped by One-Half. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(12):762.

- Deutchman ME, Sills D, Connor PD. Perinatal outcomes: a comparison between family physicians and obstetricians. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1995;8(6):440-447.

- Nesbitt TS. Obstetrics in family medicine: can it survive? J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15(1):77-79.

- Goldstein JT, Hartman SG, Meunier MR, et al. Supporting family physician maternity care providers. Fam Med. 2018;50(9):662-671. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2018.325322

- Barreto TW, Eden AR, Petterson S, Bazemore AW, Peterson LE. Intention Versus Reality: Family Medicine Residency Graduates’ Intention to Practice Obstetrics. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(4):405-406. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2017.04.170120

- Barreto TW, Eden A, Hansen ER, Peterson LE. Opportunities and Barriers for Family Physician Contribution to the Maternity Care Workforce. Fam Med. 2019;51(5):383-388. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2019.845581

- Eden AR, Barreto T, Hansen ER. Experiences of new family physicians finding jobs with obstetrical care in the USA. Fam Med Community Health. 2019;7(3):e000063. https://doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2018-000063

- Borkan J. Immersion/Crystallization. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, eds. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999:179-194.

- Crabtree BF, Miller WL, eds. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications, Inc; 1999.

- Ahearn LM. Language and Agency. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2001;30(1):109-137. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.30.1.109

- Spinelli WM, Fernstrom KM, Britt H, Pratt R. “Seeing the Patient Is the Joy:” A Focus Group Analysis of Burnout in Outpatient Providers. Fam Med. 2016;48(4):273-278.

- Friedberg MW. Factors Affecting Physician Professional Satisfaction and Their Implications for Patient Care, Health Systems, and Health Policy. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Health, American Medical Association; 2013.

There are no comments for this article.