Background and Objectives: Primary care behavioral health (PCBH) is a service delivery model of integrated care linked to a wide variety of positive patient and system outcomes. However, considerable challenges with provider training and attrition exist. While training for nonphysician behavioral scientists is well established, little is known about how to train physicians to work efficiently within integrated teams.

Methods: We conducted a case study analysis of family medicine residencies in the military health system using a series of 30 to 45-minute semistructured interviews. We conducted qualitative template analysis of these cases to chart programs’ current educational processes related to PCBH. Thirteen individuals consisting of program directors, behavioral and nonbehavioral faculty, and residents across five programs participated in the study.

Results: Current educational processes included a variety of content on PCBH (eg, treatment for depression, clinical referral pathways, patient-centered communication), primarily using a mix of didactic and practice-based placements. Resource allocation was seen as a critical contributor to quality. There was variability in the degree to which integrated behavioral health providers were incorporated as residency faculty, such that programs where these specialists were more incorporated reported more intentional curriculum development and health care systems-level content.

Conclusions: While behavioral health content was well represented in family medicine residency curriculum, the depth and integration of content was inconsistent. More intentional and integrated curriculum accompanied faculty development and integration of behavioral health faculty. Future research should evaluate if faculty development programs and faculty status of behavioral scientists results in different educational or health care outcomes.

Primary care has remained the de facto mental health service delivery environment in the United States, as nearly half of those individuals referred for specialty care do not attend their first appointment.1 As such, there is a clear need to deliver high-quality behavioral health care integrated directly in primary care.2 Broadly speaking, a recent review summarized that integrated behavioral health care has been associated with improved access to care, improved health outcomes, higher patient satisfaction and decreased health care costs.2 Although integrated care exists across a continuum with many service delivery models, one particular model that has been well studied is the primary care behavioral health (PCBH) model. PCBH is patient-centered, with a behavioral health professional serving as a consultant to a physician-led team.3 In the PCBH model, the behavioral health consultant provides behavioral health services that are routine, accessible, and high volume, while practicing as a generalist in a biopsychosocial framework.3 The PCBH model has been practiced on a large scale in the military health system (MHS) for over 20 years,2,4 and has been evaluated positively in regards to patient satisfaction,5 provider satisfaction,6 health outcomes,7 and improved access for populations in both military and civilian settings.8 In addition to positive clinical findings, competency-based training for behavioral health care professionals in the PCBH model have been well established.9 Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest family medicine resident confidence in treating behavioral health conditions is enhanced by working with behavioral health consultants.10 However, there is less agreement on broader training focusing on how family physicians can work with and leverage these behavioral health assets as part of their health care team.11

Although the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Milestones recognize the critical role behavioral health plays in family medicine, and behavioral faculty are a mainstay of residency training programs,12 there is little systematic understanding of training in integrated behavioral health service delivery models.11,13 A recent scoping review identified that while a large number of training programs in family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics include interprofessional training in behavioral health, there is little formal identification of service delivery models or intentional curriculum on health care team integration.13 This is a critical gap, as education and shared goals are key aspects of building successful health care teams.14 A more robust understanding of educational processes could address some of the known challenges with behavioral health provider attrition in PCBH practice15 and improve physician burnout, as high-functioning interprofessional teams have been seen as a protective factor in physician well-being.16

Graduate medical education represents a crucial time point in training, and family medicine residencies in particular are well suited for this exploration given their emphasis on biopsychosocial contributors to health.12 Thus, this study sought to explore the current state of training in integrated behavioral health care within family medicine residencies by starting with an initial exploration of educational aspects of integrated behavioral health training in military residencies. We selected a qualitative approach as the most appropriate methodology to allow rich contextual themes to emerge that may otherwise be missed.

Using a constructivist approach, we conducted a series of 13 qualitative interviews. Our research team included a PCBH expert behavioralist, two experts in medical education, including one in curriculum design and another in qualitative methodology, and an experienced family physician who is an expert military health care leader.

Sample

We recruited interviewees from five Department of Defense (DoD)-sponsored family medicine residency programs. DoD-sponsored residencies have several attributes that support this study. Firstly, the MHS has a long-standing tradition of practicing PCBH, thus, it provides a glimpse into how training programs might exist within an ideal state of PCBH implementation, avoiding confounding implementation with integration. Secondly, as a closed health care system, there is more standardization across practices, whereby key differences that emerge may be particularly informative. Also, although civilian health care settings may lack the history of integration or the standardization across diverse settings, findings from the MHS have been shown to provide critical insight across the health care landscape in other areas of study, in part by limiting extraneous variables.17

The lead author identified and recruited participants between January 2017 and January 2019 using purposive sampling of practice sites to ensure diversity across all military services. Participants included program directors, behavioral and nonbehavioral family medicine faculty, and residents at DoD-sponsored family medicine residencies. We selected five sites—which we treated as individual cases—for inclusion in the current study to ensure each service branch was represented along with a focus on geographic diversity, out of a total of 15 DoD-sponsored family medicine residencies. Sites were geographically located across the majority of regions in the United States and included training programs located in smaller towns, as well as small and large metropolitan areas. Each case was created by conducting an interview with stakeholders from a single site with a focus on perspective across the different types of individuals involved in family medicine residency training in PCBH (program director, behavioral and nonbehavioral faculty, and residents). Individuals who expressed interest after recruitment completed an informed consent process to include consent for audio recording and then completed the in-depth interview described below. At the conclusion of the interview, participants provided additional participant suggestions for each case using a snowball sampling technique.

Data Collection

The lead author conducted a 30 to 45-minute, in-depth, semistructured interview with each participant via phone. The interview guide was developed as part of a broader exploration of perceptions on integrated care in family medicine residencies, and is available upon request from the lead author. We conducted 13 individual interviews across the five residency training sites selected. Although saturation of themes was achieved with the first four residency sites, we recruited an additional site to ensure representation across all three military medical services, in case service-specific training differences emerged. This additional case did not yield new themes, but reinforced the conclusion that saturation had been reached. Within each case, while each stakeholder had some unique perspectives, there was a large degree of convergence, suggesting that the behavioral health curriculum was consistently identified and understood within the residency program.

Data Analysis and Orienting Framework

Interviews were transcribed and analyzed using a template-driven approach18 based on the 3P model as an orienting framework. The authors selected this model by the authors following a recent scoping review in this area that utilized the 3P model as a framework.13 The 3P model focuses on three components that represent the context, educational milieu, and outcomes, labeled as presage, process, and product factors.19 Presage factors focus on the preconditions of training (eg, what previous attitudes do learners come in with, or what faculty development has been given). Process factors explore how learning occurs (eg, do residents have choice in the behavioral health didactic curriculum during residency?), and product factors focus on the outcomes of the training program (eg, resident satisfaction, competency evaluations, or patient health measures). The aforementioned review revealed that previous training in PCBH in GME is lacking, thus limiting the relevance of presage factors. Additionally, tracking outcomes in this area was limited, thus restricting the potential relevance of product factors. Therefore this study was focused primarily on understanding the educational process regarding PCBH within family medicine residencies. However, while we used the 3P model as a framework and the recent review to guide our focus on process factors, consistent with the iterative process of template analysis, we also allowed data to inform additional themes.

Consistent with template analysis, we iteratively revised codes and reinforced the focus on process factors after using an orienting framework to begin coding. All authors participated in the coding process and agreed on final coding. Forty percent of the cases were coded by all authors in an iterative format and subsequently discussed until overall agreement was reached. The lead author primarily coded the remaining cases. The Uniformed Services University Institutional Review Board approved this protocol.

Participants described the curriculum associated with PCBH within their residency program. Using a coding scheme informed by the 3P model and refined by a recent related scoping review,17,19 we focused on defining the educational content and methodology, and looked for evidence of intentional curriculum development on the basis of findings noted from the recent review and based on themes that emerged in our data. We also evaluated barriers and facilitators of the educational process. Figure 1 displays a summary of our themes and subthemes.

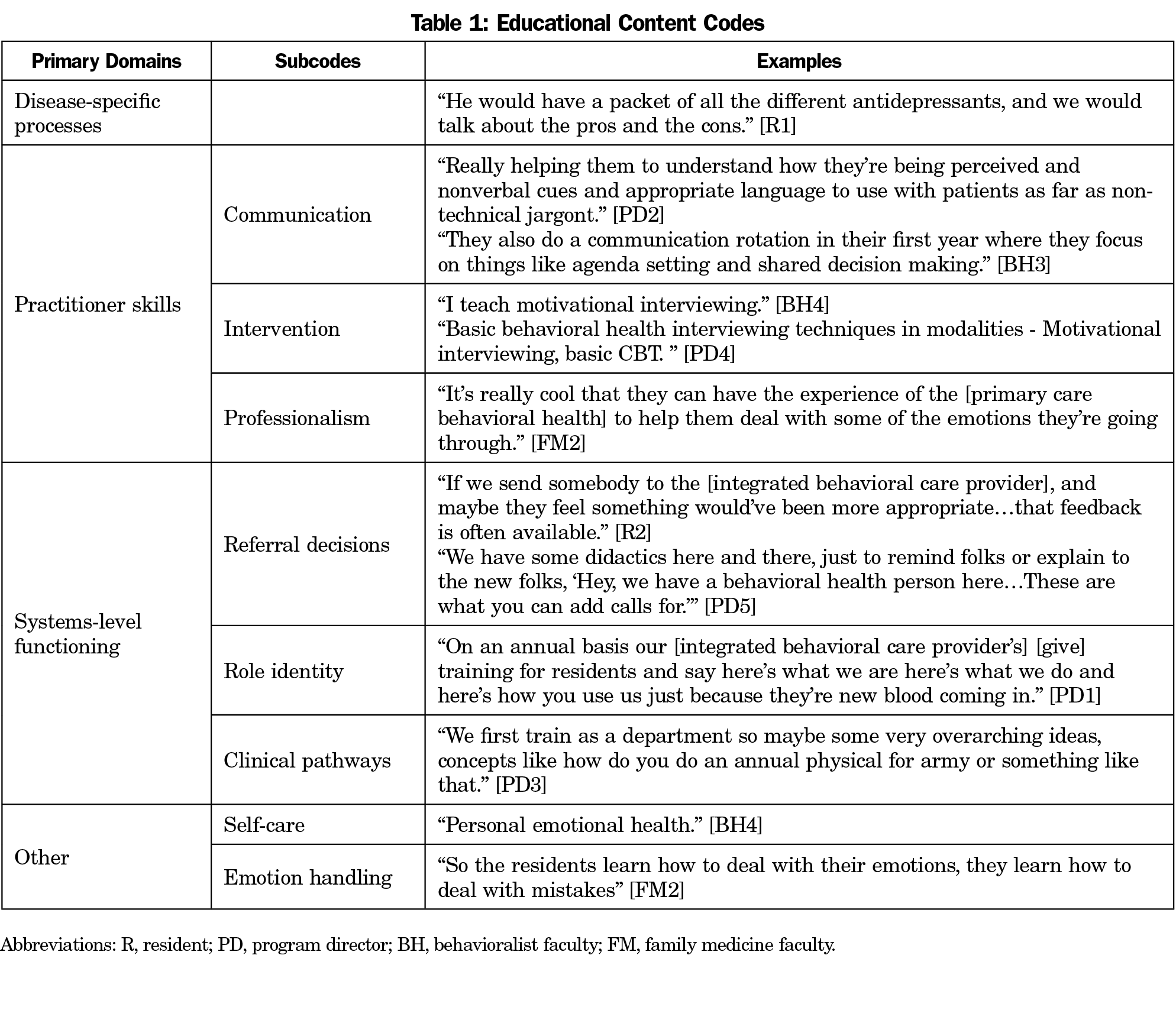

Educational Content

Broadly, educational content was grouped into four categories: (1) disease-specific processes (eg, diabetes management, depression, anxiety), (2) practitioner skills (eg, communication, motivational interviewing, consultation), (3) systems-level functioning (eg, clinical pathways, interprofessional roles), and (4) other content that did not fit within these identified categories. Table 1 shows exemplar quotations for each primary code and associated subcodes. Across all sites, a wide range of PCBH-related content was covered. It was not always clear whether or not this educational content was delivered within the explicit context of integrated care (as opposed to general behavioral health), but findings represent attempts to ensure a wide breadth of curricular content in behavioral health within family medicine residencies. While professionalism was a common theme endorsed across programs, many programs also highlighted provider wellness and resilience as a component of this curriculum.

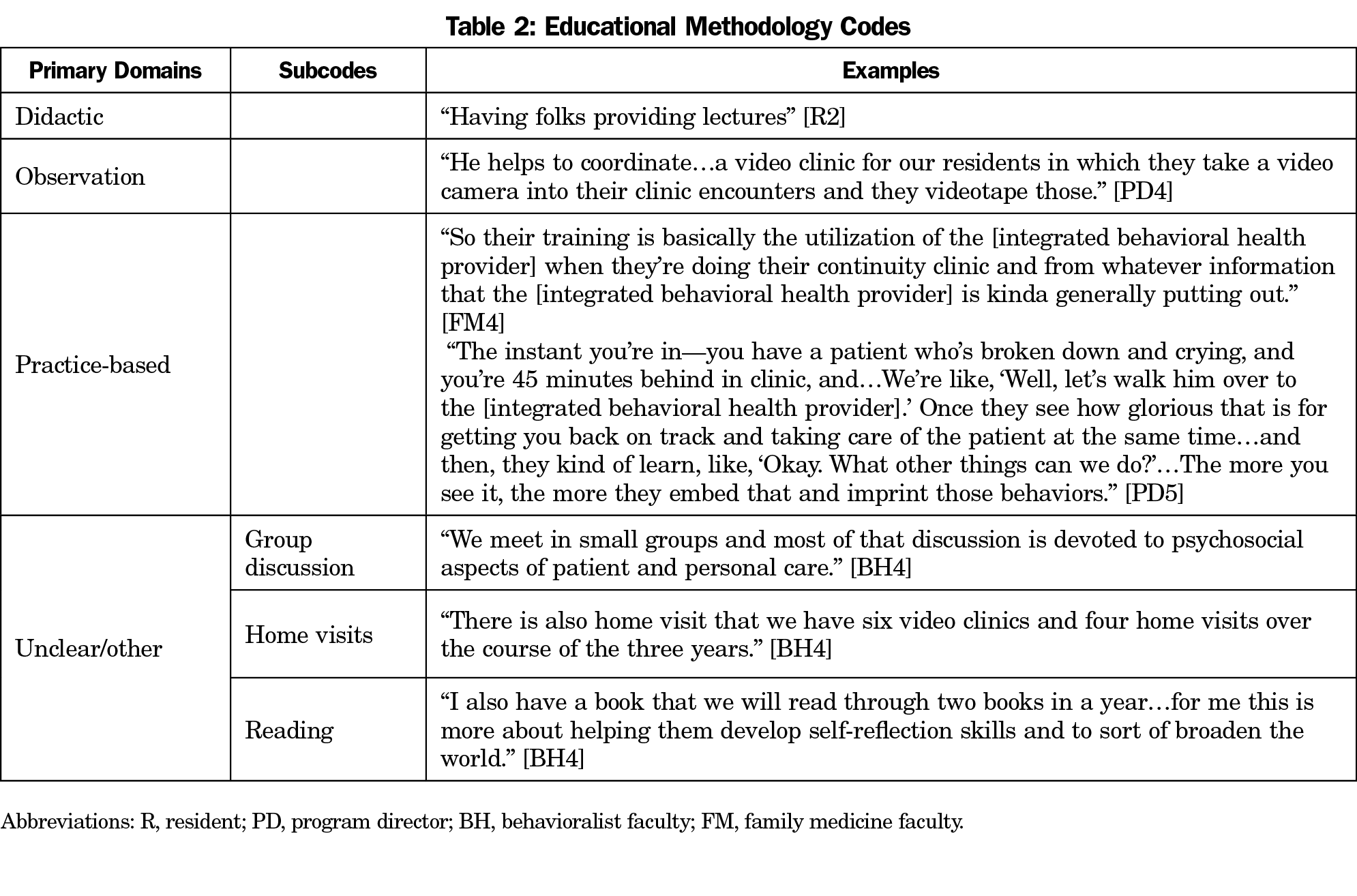

Educational Methodology

We identified five educational methodologies: didactic, observational, simulation, records audit, action/practice-based, and also allowed for categorization as other or unclear. Table 2 shows exemplar quotations for each primary code and associated subcodes. While educational methods employed varied similarly, didactics and placement-based learning was predominant, and usage of simulation and audit methodology was not reported. Furthermore, placement-based learning was often cited as the primary means for learning specifically about PCBH practices, although this was often less intentional and structured than other methods employed.

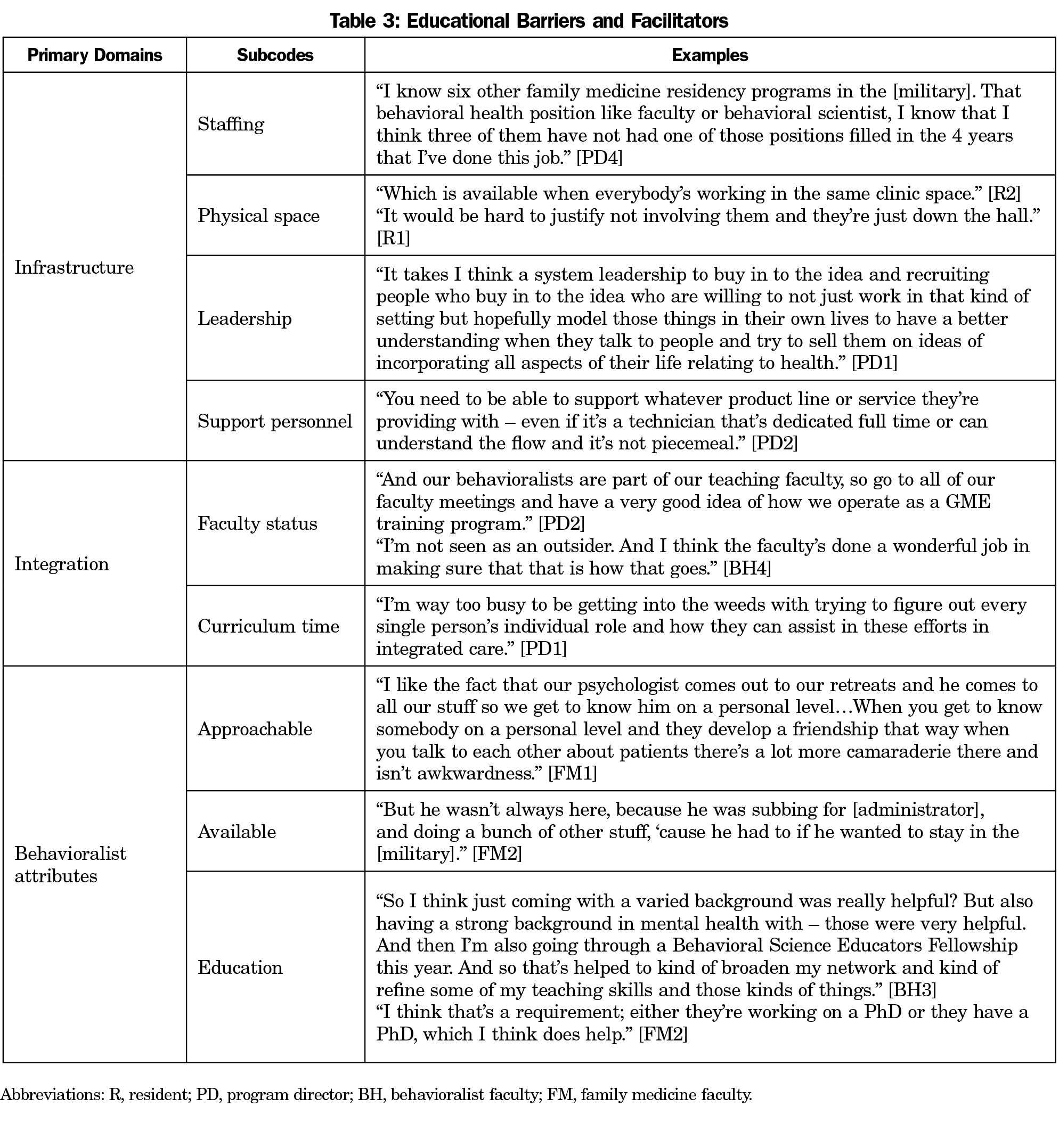

Educational Barriers and Facilitators

We developed codes on educational barriers and facilitators in addition to coding elements of the educational process. In many cases, the same underlying principle was identified as a barrier in cases where it was absent, and facilitator in cases when it was present. Thus, these codes were combined, and are shown with subcodes and illustrative examples in Table 3. A primary theme that emerged was staffing–having a consistent individual who filled the role of providing PCBH-related content. In addition to the presence of a dedicated individual to teach PCBH principles, their integration within the residency program was another noted theme. In some cases, they were considered part of the faculty, had leadership support, and were readily available and approachable. In other cases, they were additional clinical staff the residents interacted with but were not considered faculty. In the latter cases, those programs tended to have less formal intentional curriculum and relied more heavily on action-based placements. While action-based placements are educationally prudent, these programs also had less evaluation and demonstration of understanding of the impacts of learning by working alongside integrated behavioral health assets. To a lesser extent, the educational background of the behavioral practitioner, the time within the academic curriculum, and provider stigma and comfort were noted as themes. Finally, although not across all sites, physical space limitations and other infrastructure concerns were noted as playing a role in the effectiveness of the PCBH-focused curriculum.

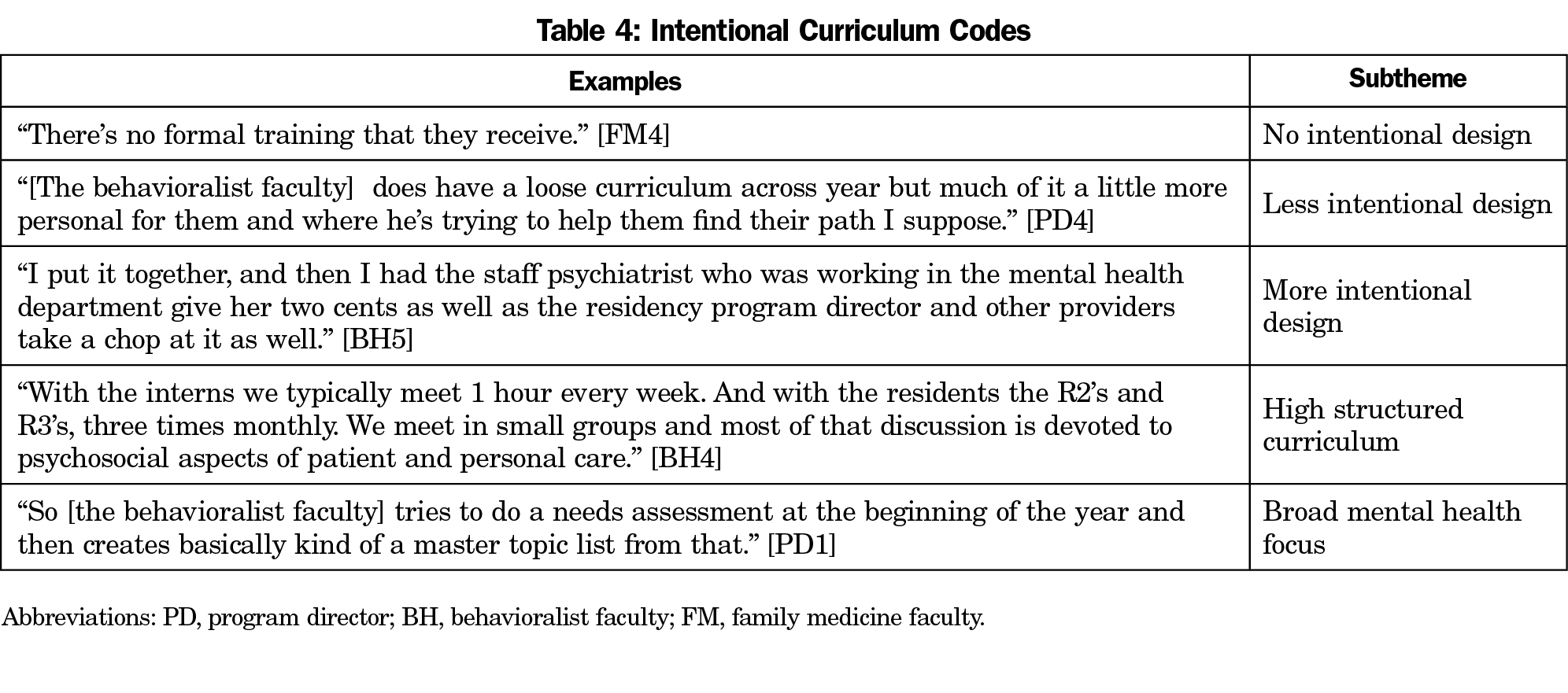

Additional Themes

Consistent with the iterative nature of template analysis, we also noted other emergent themes within the orienting framework of the 3P model. One unique theme that emerged was focus on the process of curriculum development, and in particular, evidence of intentional curriculum design. Table 4 presents exemplar quotes from this theme. In this regard, there was considerable variability across sites. While every site demonstrated some thought and intentionality to behavioral health curriculum as a whole, some sites focused on behavioral health more broadly. We noted a varying degree of intentional curriculum development, from no formal training to more iterative evaluation across multiple faculty members.

Qualitative analysis of DoD-sponsored family medicine residencies revealed broad and diverse content pertaining to behavioral health. Across all military services, there was a clear effort and intent to include a wide variety of behavioral health content. There was also a recognition that increased integration of a behavioral health specialist as faculty provided increased structure to the curriculum. These findings may portend an overall respect for the importance of behavioral health in primary care. There was a less explicit and specific focus on integrated care and the specific care delivery model practiced within the DoD, but systems-level factors were still addressed at several points. Another content area that emerged as an important focus across medical education was that of wellness and resilience. Training in PCBH was often associated with perceived benefits for wellness and with resilience curriculum programming. While not directly assessed, this aligns with literature suggesting that increased integration promotes teamwork and well-being amongst health care team members16 and may be relevant to the issue of heightened rates of physician burnout.20 This finding is consistent with literature identifying communication and teamwork as critical competencies for physicians working in integrated behavioral health.11 Future research may explore these links more directly, and could inform critical interventions for this population.

When exploring how PCBH content was delivered, findings suggested that while disease-specific processes may often be taught in a didactic fashion, the majority of integrated care specific content was delivered through practice based placements. Often times, this meant working alongside a behavioral health consultant, and this may or may not have been an explicit educational objective communicated to residents. While the value of PCBH has been recognized more broadly in the literature2,4-8 and was consistent with comments made by faculty when describing practice-based placements during interviews, it may be worth considering how explicit highlighting of this objective may further enhance the educational quality of the experience.

Finally, in exploring factors that facilitated or hampered education in PCBH, several general themes emerged. The first was resource allocation. When programs were limited by staffing or physical space, this tended to have a significant negative impact on the PCBH curriculum, and the opposite was true when those resources were readily available. The second pertained to the primary instructor of the behavioral health curriculum. In cases where the PCBH curriculum appeared the most intentional and robust, the behavioral health consultant who practiced PCBH was also well integrated into the family medicine residency faculty. For programs wishing to improve curriculum in this area, this may be an important consideration. Finally, behavioral health faculty varied in their background and experience with education and curriculum development. This is an important consideration not only in selection, but also in faculty development for these individuals within a residency program.

Limitations

This study has limitations. For one, it focused exclusively on military family medicine residencies. The military is a managed care organization that does not operate on a fee-for-service basis. This lends itself to incentivizing preventative and primary care in ways that may be different in other health care settings. Additionally, the military’s GME pipeline directly feeds its workforce, thus there may be unique incentives for training in specific care delivery models that are practiced across the military health care infrastructure. However, although some of the particular examples that emerged in the data are military-specific (eg, certain sites employed active duty and thus were more likely to fill the position, but then had to contend with turnover associated with military reassignment), the general principles of turnover and attrition also appear in civilian health care settings.21 Although reasonable that many of these concepts would apply to civilian health care settings, it is important to recognize the specificity of sampling was intentional to capture perspective within military residencies, and future research may explore if similar themes are noted in civilian settings and what—if any—key differences emerge.

It is also important to acknowledge some methodological decisions that may influence the findings and should be thoughtfully considered. While the 3P model is a recognized framework for interprofessional education,19 it is not the only model, nor is it an evaluative model. We selected it as an orienting framework to parallel existing literature reviewed in this area, but other frameworks may be considered to better understand different parts of the behavioral health educational experience in family medicine residencies, both in the military and civilian settings. Additionally, observational and ethnographic approaches could be included to further enhance the diversity of perspectives included in the case study by selecting multiple informants. Finally, as noted in previous reviews,2,9 there was a challenge in coding PCBH elements, in part due to variability of integrated care models implementation. This is particularly noteworthy in a more standardized and structured system with long-term implementation of a specific integrated care model. It is important for future research to explore if critical differences emerge across different integrated care models in regards to physician training. The literature must become more consistent in its definition and description of key elements of established care models.

Conclusions and Future Directions

These findings provide a critical first step in charting the nature of PCBH training within family medicine residencies. By exploring a health care system where PCBH has been well established and is the norm for care, we gain critical insight into potential best practices. Building an intentional curriculum around practice-based placement experiences in behavioral health, providing appropriate resources to support behavioral health integration, and intentionally including behavioral health providers as residency faculty are three such approaches supported by our study. While PCBH was recognized and appreciated, especially in practice-based contexts, there was no consistent systematic program evaluation to inform whether or not the additional resource investment in an intentional curriculum or faculty development would produce an appreciable change in outcomes, either within the resident, or the health care system. These are important future directions for research. Ultimately, improving integration from the perspective of all health care team members is likely to yield an improved patient experience, improved patient health, and more a effective health care system.

Acknowledgments

Disclaimer: This article was authored by employees of the United States government. Any views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the United States government, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the Department of Defense.

Funding Statement: Funding for this project was provided by the Uniformed Services University Department of Family Medicine.

References

- Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA. 2006;295(9):1023-1032. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.9.1023

- Hunter CL, Funderburk JS, Polaha J, Bauman D, Goodie JL, Hunter CM. Primary care behavioral health (PCBH) model research: current state of the science and a call to action. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2018;25(2):127-156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-017-9512-0

- Reiter JT, Dobmeyer AC, Hunter CL. The Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) model: an overview and operational definition. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2018;25(2):109-126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-017-9531-x

- Hunter CL, Goodie JL. Behavioral health in the Department of Defense Patient-Centered Medical Home: history, finance, policy, work force development, and evaluation. Transl Behav Med. 2012;2(3):355-363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-012-0142-7

- Runyan CN, Fonseca VP, Meyer JG, Oordt MS, Talcott GW. A novel approach for mental health disease management: the Air Force Medical Service’s interdisciplinary model. Dis Manag. 2003;6(3):179-188. https://doi.org/10.1089/109350703322425527

- Landoll RR, Nielsen MK, Waggoner KKUS. US Air Force Behavioral Health Optimization Program: team members’ satisfaction and barriers to care. Fam Pract. 2017;34(1):71-76. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmw096

- Bryan CJ, Corso ML, Corso KA, Morrow CE, Kanzler KE, Ray-Sannerud B. Severity of mental health impairment and trajectories of improvement in an integrated primary care clinic. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(3):396-403. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027726

- Ogbeide SA, Landoll RR, Nielsen MK, Kanzler KE. To go or not go: patient preference in seeking specialty mental health versus behavioral consultation within the primary care behavioral health consultation model. Fam Syst Health. 2018;36(4):513-517. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000374

- Dobmeyer AC, Hunter CL, Corso ML, et al. Primary care behavioral health provider training: systematic development and implementation in a large medical system. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2016;23(3):207-224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-016-9464-9 PMID:27484777

- Hemming P, Hewitt A, Gallo JJ, Kessler R, Levine RB. Resident’s confidence providing primary care with behavioral health integration. Fam Med. 2017;49(5):361-368.

- Martin M, Allison L, Banks E, et al. Essential skills for family medicine residents practicing integrated behavioral health: A Delphi study. Fam Med. 2019;51(3):227-233. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2019.743181

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and American Board of Family Medicine. The Family Medicine Milestone Project. 2015. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/FamilyMedicineMilestones.pdf?ver=2017-01-20-103353-463. Accessed November 8, 2019.

- Landoll RR, Maggio LA, Cervero RM, Quinlan JD. Training the Doctors: A Scoping Review of Interprofessional Education in Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH). J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2019;26(3):243-258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-018-9582-7

- D’Angelo MR, Saperstein AK, Seibert DC, Durning SJ, Varpio L. Military interprofessional health care teams: how USU is working to harness the power of collaboration. Mil Med. 2016;181(11):1404-1406. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00558

- Landoll RR, Nielsen MK, Waggoner KK. Factors affecting behavioral health provider turnover in U.S. Air Force primary care. Mil Psychol. 2018;30(5):398-403. https://doi.org/10.1080/08995605.2018.1478549

- Welp A, Manser T. Integrating teamwork, clinician occupational well-being and patient safety - development of a conceptual framework based on a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):281. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1535-y

- Landoll RR, Nielsen MK, Waggoner KK, Najera E. Innovations in primary care behavioral health: a pilot study across the U.S. Air Force. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(2):266-273. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/iby046

- Liaw W, Eden A, Coffman M, Nagaraj M, Bazemore A. Factors Associated With Successful Research Departments A Qualitative Analysis of Family Medicine Research Bright Spots. Fam Med. 2019;51(2):87-102. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2018.652014

- Reeves S, Fletcher S, Barr H, et al. A BEME systematic review of the effects of interprofessional education: BEME Guide No. 39. Med Teach. 2016;38(7):656-668. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2016.1173663

- Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Balance in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023

- Sinsky CA, Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Tutty M, Shanafelt TD. Professional Satisfaction and the Career Plans of US Physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(11):1625-1635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.08.017

There are no comments for this article.