Background and Objectives: Little is known about how family medicine clerkship directors (FMCDs) handle reports of student mistreatment. We investigated FMCDs’ involvement in handling and resolving these reports.

Methods: We collected data as part of the 2019 CERA survey of FMCDs. FMCDs provided responses on how they handled student mistreatment reports and their comfort level in resolving these reports.

Results: Ninety-nine out of 142 FMCDs (69.7%) responded to the survey. Regarding mistreatment reports, 24.2% of FMCDs had received at least one report of student mistreatment about full-time faculty in the past 3 years, compared to 64.6% of FMCDs receiving at least one report about community preceptors (P<.001). Regarding who determined the response to the mistreatment, 13.1% of FMCDs were the highest level of leadership responsible for stopping use of a full-time faculty member for mistreatment concerns, while 42.4% of FMCDs were the highest level of leadership responsible for stopping use of a community preceptor. Regarding their comfort level in resolving mistreatment reports, 59.1% of FMCDs were either somewhat or very comfortable resolving a mistreatment report about a community preceptor, while only 48.9% reported those comfort levels for full-time faculty. FMCDs who had previously stopped using full-time faculty and/or community preceptors due to mistreatment reports were less likely to feel comfortable with resolving reports about full-time faculty compared to those who had no such experience (P=.03).

Conclusions: FMCDs more frequently receive mistreatment reports about community preceptors than full-time faculty and are more likely to be the highest decision maker to stop using a community preceptor for mistreatment concerns. Further study is needed to elucidate factors that affect FMCDs’ comfort in handling student mistreatment reports.

Medical student mistreatment, defined as behaviors that show “disrespect for the dignity of others and unreasonably interferes with the learning process,”1 is an important issue in medical education. Studies have demonstrated that mistreatment leads to long-term adverse effects in students and residents such as symptoms of posttraumatic stress,2 burnout,3-4 and suicidal thoughts.4 It is concerning that despite efforts from multiple medical schools to address student mistreatment5 and national monitoring for nearly 30 years by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Graduation Questionnaire,1 notable proportions of medical students in 2019 continued to report one or more incidents of humiliation (22.7%), unwanted sexual advances (4.8%), being denied opportunities for training or rewards based on gender (6.2%), sexist (15.8%), and racially or ethnically offensive (8.5%) remarks/names during their undergraduate medical education by other health care members.6 Fried and colleagues found that despite comprehensive changes to policy and educational interventions targeted at faculty and residents at their institution over a 13-year period, student reports of mistreatment persisted.7 While they hypothesized that the hidden curriculum weakened efforts to improve mistreatment, a critical question remains as to why student mistreatment still persists in our learning environments.

While baseline data on mistreatment during medical school is available,6 little research exists regarding student experiences of mistreatment specific to family medicine clerkships. The nature and frequency of student mistreatment varies between clinical clerkships,8,9 so limited information about the family medicine context may inhibit an effective response. Breed et al’s single-institution study found 2% of 122 students reported being “threatened with physical harm” and another 2% reported being “denied opportunities for training or rewards based solely on gender” during their family medicine clerkship.8 For several other types of mistreatment on the survey, there were no reports of mistreatment on the family medicine clerkship,8 though this could be due to underreporting (eg, 76.8% of students who reported experiencing mistreatment on the 2019 AAMC Medical School Graduation Questionnaire indicated they did not report those incidents of mistreatment6). Another study reported that preceptors were less likely to be the source of mistreatment and that mistreatment occurred less often on family medicine clerkships compared to surgery, obstetrics-gynecology, and internal medicine clerkships.9

We found no reports on how family medicine (FM) clerkship directors handle reports of student mistreatment on their clerkship. For years, FM clerkships have used both full-time faculty and volunteer community physicians (community preceptors) as clinical teachers for their clerkship students.10 In a 2018 survey of FM clerkship directors, 85.3% reported that some of their students spent at least half of the rotation time in the practice of a community preceptor during their clerkship.11 While we hypothesized that medical school administrators and department chairs most often handle reports of student mistreatment by full-time faculty, FM clerkship directors may be in the unique position of addressing reports of student mistreatment by their community preceptors employed by outside practices. FM clerkship directors may need to determine what action to take in response to student mistreatment reports and decide whether to temporarily or permanently terminate the services of the community preceptors in these instances.

Contextual factors may affect how a FM clerkship director handles these reports. One factor is community preceptor employment status at the medical school. Another factor is a school’s ability to recruit and maintain a sufficient number of preceptor sites for their FM clerkship and other ambulatory courses.12 Does an insufficient number of preceptor sites and the need for more preceptors affect the FM clerkship director’s comfort in stopping the use of a full-time faculty or community preceptor? Finally, preceptor compensation could impact handling of mistreatment reports; for example, schools that pay their community preceptors13 may have the opportunity to choose higher-quality precepting sites.14

Overall, there has been little examination of how such structural and procedural elements of family medicine clerkships may affect student mistreatment issues, or influence identification and implementation of an effective response. Our study investigated how often family medicine clerkship directors handle student mistreatment concerns on their clerkship and the process used to investigate and resolve the concerns. We hypothesized there may be differences in how mistreatment concerns about full-time faculty and community preceptors are handled and we sought to elucidate these differences. Finally, we measured FM clerkship directors’ comfort in handling student concerns about full-time faculty and community preceptors and explore if contextual factors contributed to their comfort level.

Our study analyzed data obtained as part of the 2019 Council of Academic Family Medicine (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) Family Medicine Clerkship Director Survey. The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved the study in June 2019, and the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved it in September 2019.

Survey Administration and Development

CERA conducts regular surveys of family medicine educators (membership of the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine, department chairs, residency directors, and clerkship directors).15 The cross-sectional survey of family medicine clerkship directors is distributed annually to clerkship directors or their designees at the main campus of qualifying medical schools (US or Canadian medical schools accredited by the Liaison Committee for Medical Education [LCME] or Committee on Accreditation of Canadian Medical Schools [CACMS]). In 2019, 126 US and 16 Canadian individuals were eligible to complete the survey in their roles as family medicine educators directing a family medicine or primary care clerkship.

CERA sent an email to eligible clerkship directors and designees on June 19, 2019, inviting them to participate in the CERA Clerkship Director survey. A link to the online survey administered with the online program SurveyMonkey (San Mateo, CA) was included in the email. While the survey was open, CERA was informed of 19 changes in the clerkship director position, 9 through contact with the survey director and 10 through the survey itself. All new clerkship directors were subsequently invited to participate in the survey. CERA sent weekly reminders up to four times to all nonrespondents, and sent a final invitation on July 31, 2019, before the survey closed on August 2, 2019.

Survey Questions

The CERA survey included a set of demographic questions about clerkship directors as well as questions submitted by CAFM members that addressed a variety of subjects, including our 10 survey items on student mistreatment. Our questions included the number of mistreatment reports received about full-time faculty and community preceptors within the past 3 years, who had primary responsibility in investigating the reports, what was the highest level of leadership (eg, clerkship director, department vice chair or chair, assistant dean, associate dean or dean) who made the final decision to stop using a full-time faculty or community preceptor, whether the clerkship had stopped using a full-time faculty member or community preceptor due to mistreatment reports, adequacy of the number of preceptor sites and the clerkship director’s comfort level in handling mistreatment reports about a full-time faculty member or a community preceptor. The FM clerkship directors rated their comfort level in handling mistreatment reports using a 5-point Likert scale with the following responses: 1=very uncomfortable; 2=somewhat uncomfortable; 3=neither uncomfortable or comfortable; 4=somewhat comfortable; 5=very comfortable.

Survey Definitions

In our survey, our specified definition of mistreatment was a slight modification of the definition used in the Association of American Medical Colleges Graduating Questionnaire. We used the definition, “Mistreatment can be intentional or unintentional and occurs ‘when behavior shows disrespect for the dignity of others and unreasonably interferes with the learning process. Examples of mistreatment include sexual harassment; discrimination or harassment based on race, religion, ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation; humiliation; psychological or physical punishment; and the use of grading and other forms of assessment in a punitive manner.’”1 We defined a full-time faculty member as “a physician employed by the medical school and has a primary appointment in the department of family medicine.” We defined a community preceptor as “a physician employed by an outside practice, who teaches clerkship students in his/her office. Some schools give community preceptors a volunteer faculty appointment.”

Analysis

We analyzed our data with SPSS Version 26 (Armonk, NY) using descriptive statistics and tests of association including tests for group differences (ie, χ2 test for association, Wilcoxon paired-signed rank), z-tests for difference in proportions, and Pearson correlations. Valid-response percentages were reported so that missing responses are excluded from analysis, but “n/a or unsure” responses were included in the denominator count unless otherwise noted. Response options were dichotomized for χ2 analysis to promote clarity of findings.

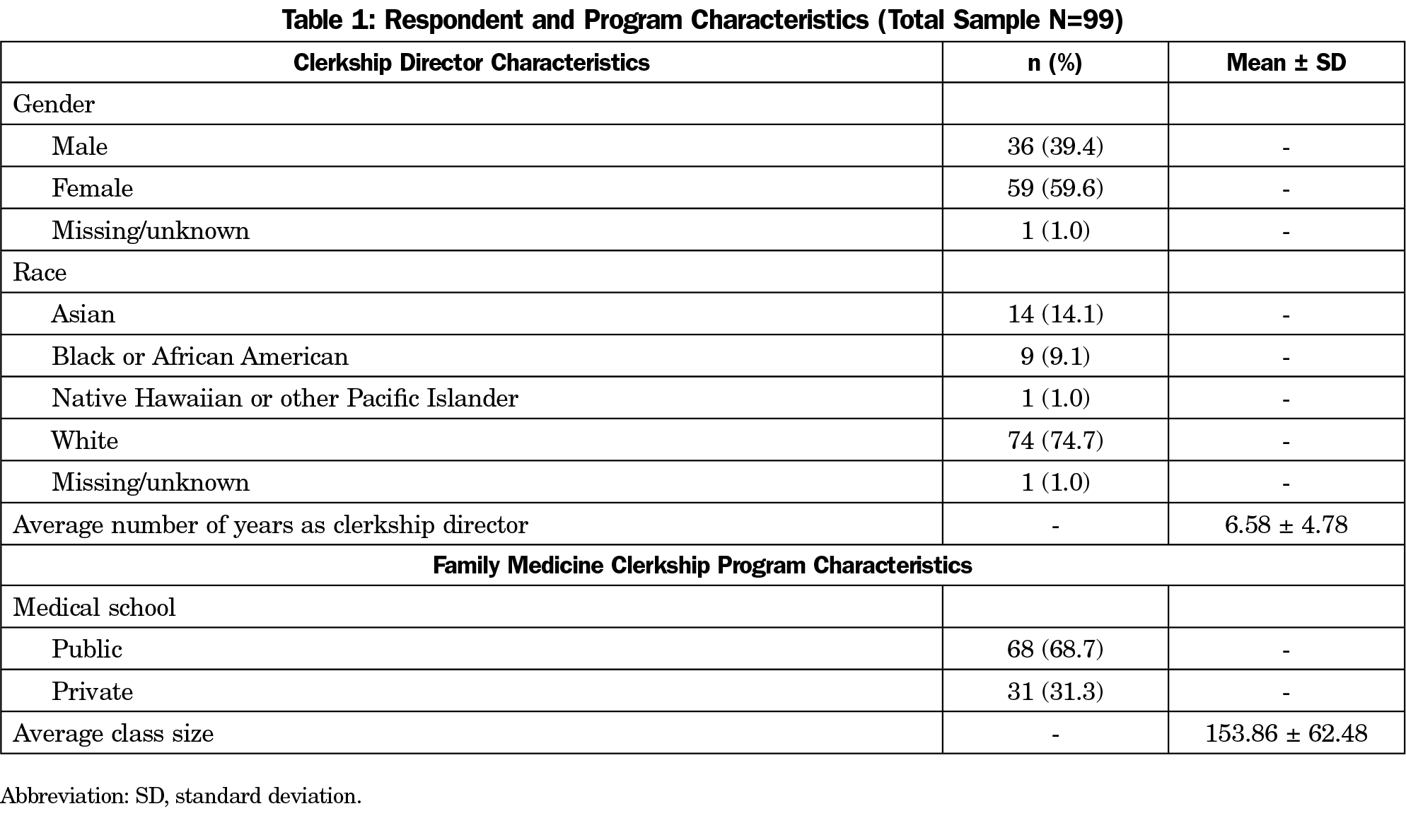

A total of 99 of 142 clerkship directors (69.7% response rate) responded to our mistreatment survey items (Table 1). The majority of respondents (n=60, 61.9%) reported being always, very often, or somewhat often short of preceptors/sites.

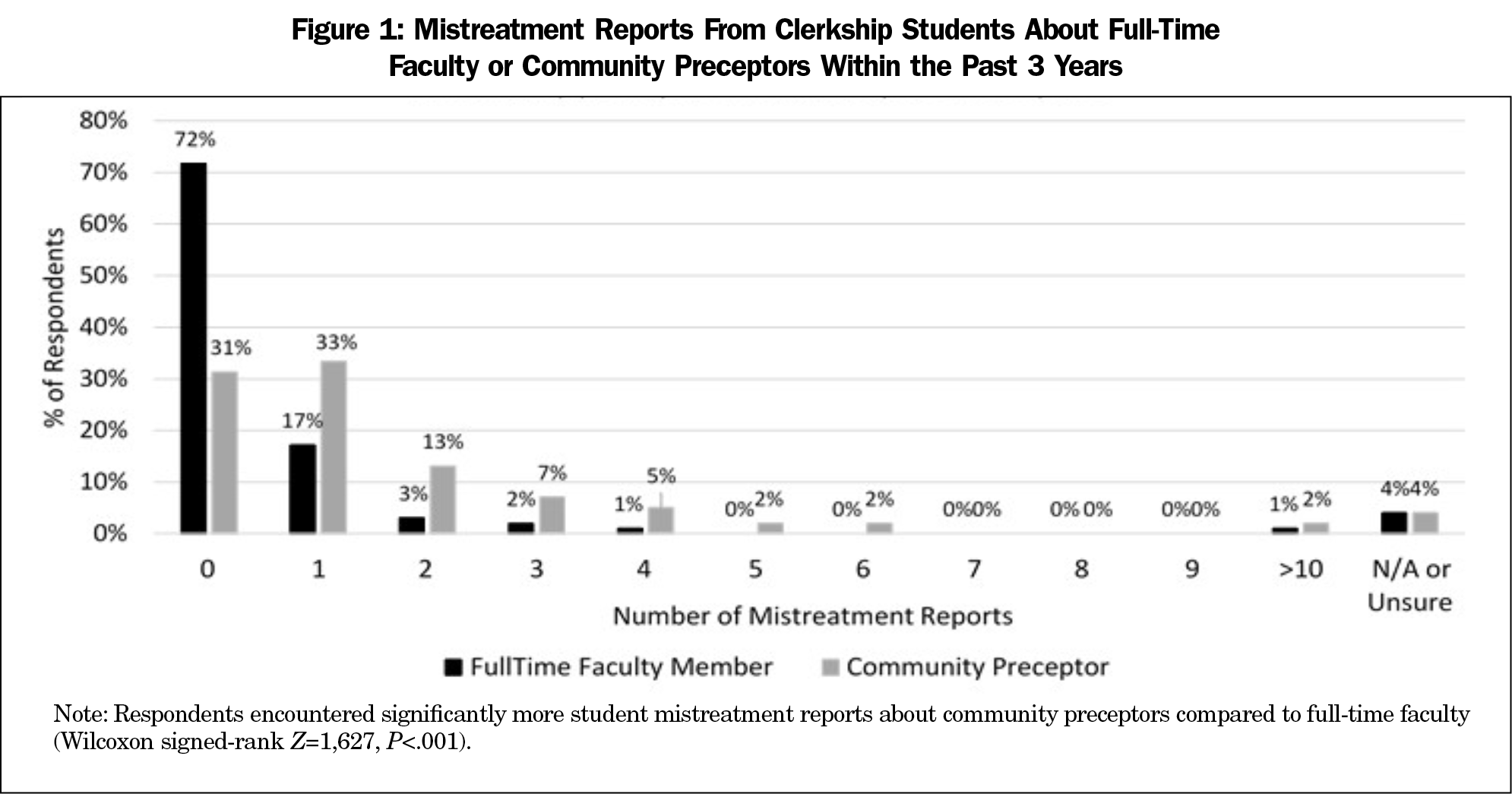

The majority (n=64, 64.6%) of respondents received at least one mistreatment report from clerkship students about a community preceptor and 24.2% (n=24) received at least one report about a full-time faculty member (Figure 1). Overall, FM clerkship directors encountered significantly more student mistreatment reports for community preceptors compared to full-time faculty (Wilcoxon signed-rank Z=1,626.50, P<.001).

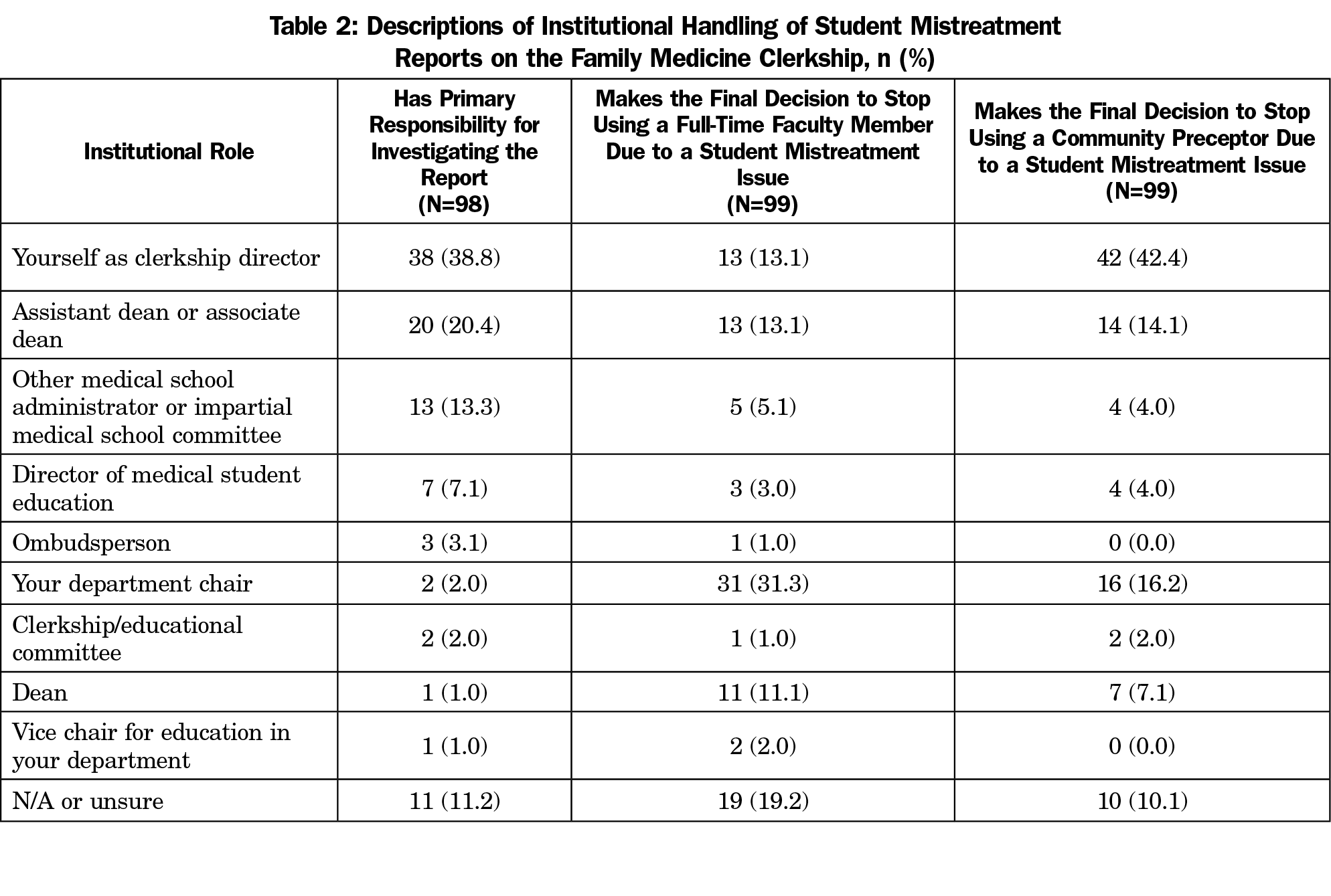

The largest proportion of respondents (n=38, 38.8%) reported that FM clerkship directors had primary responsibility for investigating student mistreatment reports on the family medicine clerkship, while 20.4% (n=20) reported that it was an assistant/associate dean, and 13.3% (n=13) reported that it was another medical school administrator or impartial medical school committee (Table 2).

Regarding the highest level of leadership who makes the decision to stop using a full-time faculty member due to a student mistreatment issue, 31.3% (n=31) of respondents reported that the department chair makes the decision, 24.2% (n=24) reported that an assistant dean, associate dean or dean makes the decision, and 13.1% (n=13) reported that the FM clerkship director makes the decision (Table 2). In contrast, for the highest level of leadership who makes the decision to stop using a community preceptor due to a student mistreatment issue, 42.4% (n=42) reported that the FM clerkship director makes the decision, 21.2% (n=21) reported that an assistant dean, associate dean, or dean makes the decision, and 16.2% (n=16) reported that the department chair makes the decision. Overall, there was no clear single role with the primary responsibility of investigating student mistreatment reports or making the final decision to stop using a faculty or community preceptor due to mistreatment issues.

Due to student mistreatment issues, 12 (12.2%) respondents stopped assigning students to a full-time faculty member(s) and 55 (56.1%) respondents stopped assigning students to a community preceptor(s) in their family medicine clerkships. In contrast, 34 (34.7%) respondents had never stopped sending students to a full-time faculty member or community preceptor due to student mistreatment issues. Since respondents may have stopped assigning students to both full-time faculty and community preceptors, the total percentage is greater than 100% for this finding.

Regarding comfort level with resolving student mistreatment reports about full-time faculty, Likert-style items indicated 48.9% or n=43 of 88 question respondents were either somewhat or very comfortable. In contrast, 59.1% or n=55 of 93 question respondents reported those comfort levels for resolving student mistreatment issues with community preceptors. However, a z test for difference in proportions indicates the difference between these percentages was not statistically significant (z=1.4, P=.16).

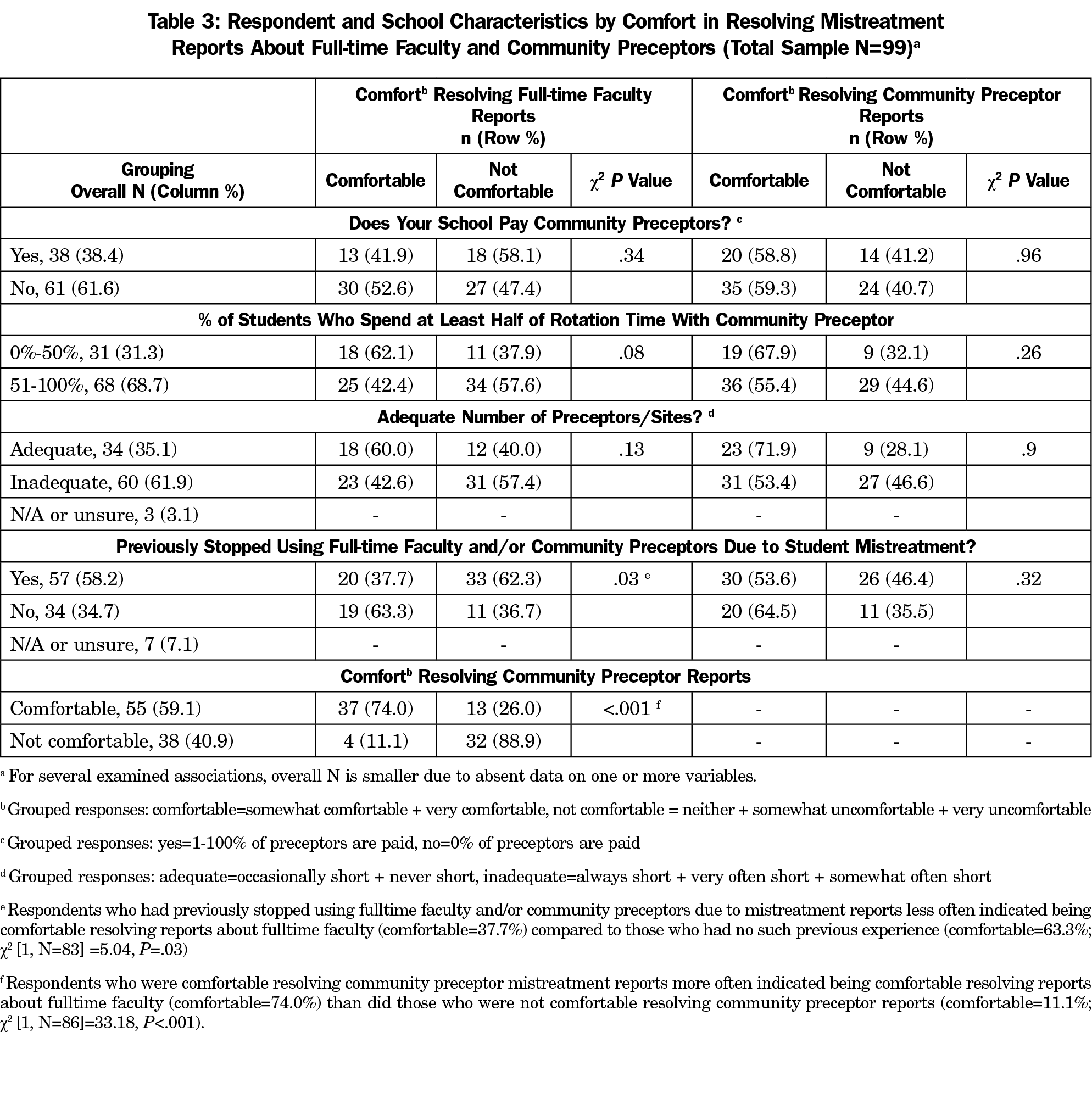

There was no correlation between years of experience as an FM clerkship director and comfort in resolving student mistreatment reports with either full-time faculty (r=-0.05, P=.67) or community preceptors (r=-0.03, P=.75). FM clerkship directors’ comfort in handling student mistreatment reports associated with either full-time faculty and/or community preceptors did not differ based on whether family medicine clerkships paid for any community preceptors, percentage of students assigned to community preceptors, or availability of community preceptors relative to need (Table 3). FM clerkship directors who had previously stopped using full-time faculty and/or community preceptors due to mistreatment reports less often indicated being comfortable resolving reports about full-time faculty (comfortable=37.7%) compared to those who had no such previous experience (comfortable=63.3%) (χ2 [1, N=83]=5.04, P=.03). Finally, FM clerkship directors who were comfortable resolving community preceptor mistreatment reports also more often indicated being comfortable resolving reports about full-time faculty (comfort=74%), than did those who were not comfortable resolving community preceptor reports (comfort=11.1%) (χ2 [1, N=86]=33.18, P<.001; Table 3).

In this exploratory study, we gained an initial understanding of how family medicine clerkship directors handle reports of student mistreatment on their clerkship. Survey respondents received student mistreatment reports about community preceptors more often than full-time faculty. Family medicine clerkship directors are actively involved in investigating student mistreatment reports. While decisions about whether to stop using a full-time faculty as a preceptor are more likely to be handled by a department chair or an official in the dean’s office, family medicine clerkship directors are more likely to make a decision to stop using a community preceptor. Our findings indicate that there are discrepancies in how student mistreatment is handled on different family medicine clerkships. Further discussion to understand the contexts of different schools and the processes used will be helpful.

Approximately 35% of FM clerkship directors reported they have never stopped assigning a student to a full-time faculty or community preceptor due to student mistreatment issues. This percentage seems high, but additional study is needed to investigate the meaning and possible causes of this result. While some FM clerkships may have only minor mistreatment issues that warrant interventions less severe than stopping the use of a clinical teacher, individual FM clerkships may need to explore more intentionally whether there are instances when their FM clerkship should stop the use of a full-time faculty or a community preceptor, but have not done so. Further research is needed to learn about possible barriers to removal of full-time faculty and community preceptors when credible student mistreatment issues become apparent.

Our tests for association indicated that comfort level in handling mistreatment reports for one type of clinical instructor (eg, full-time faculty) tended to be associated with comfort level for the other type (eg, community preceptor). This finding suggests that comfort with this task may be generalizable across instructor types, so that interventions aimed at increasing FM clerkship director comfort with following up on reports of mistreatment may not need to be tailored differently by type of instructor. We also found that FM clerkship directors with previous experience ending the use of full-time faculty and/or community preceptors following reports of mistreatment of students were less likely to feel comfortable with resolving full-time faculty reports of mistreatment, compared to those who had no such previous experience. While it may be possible that experiencing the challenging and complex nature of addressing mistreatment reports simply decreases comfort with addressing such issues again in the future, as opposed to providing practice and experience which might otherwise mitigate discomfort, the reason for this finding is not clear. Further study is needed to investigate for possible causes.

More than half of the respondents reported being short of preceptor sites at least somewhat often, confirming the shortage of community-based faculty reported elsewhere.12 However, neither this factor, nor others such as paying community preceptors, or percentage of students assigned to community preceptors, showed any association with a family medicine clerkship director’s comfort in handling student mistreatment reports. Further study is needed to identify factors which affect a family medicine clerkship director’s comfort in handling student mistreatment reports.

FM clerkship directors already have multiple responsibilities in monitoring the competence of full-time faculty and community preceptors and the learning content they provide, offering appropriate faculty development to these clinical teachers despite limited availability of time for both clerkship directors and clinical teachers, and recognizing their contributions to keep them motivated to continue teaching.16-22 Beyond those responsibilities, our findings indicate that FM clerkship directors have an important role in ensuring that full-time faculty and community preceptors provide a safe learning environment for students, in investigating reports of student mistreatment, and in being involved in decisions about whether to stop using a full-time faculty or community preceptor due to student mistreatment issues.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our understanding of the full scope of the types of mistreatment behaviors that students encounter during their family medicine clerkship was limited by the relatively small number of questions allotted to our study, and the closed-response format. Furthermore, the clinical learning environment may include instigators of student mistreatment in roles other than those captured in this study (eg, patient, staff, and nurses). Finally, the use of survey methodology also makes our study vulnerable to response bias (eg, social desirability bias), and the prompt to think of events across multiple years can produce recall bias. Our relatively small sample size may have resulted in type-2 errors, based on limited power to identify significant predictors of comfort level. Future studies, particularly qualitative or mixed-methods in nature, can build on our descriptive findings to identify the types of mistreatment behaviors encountered by students during their clerkships, common instigators of such behaviors that undermine the clinical learning environment, and how context influences the investigation and final outcome of mistreatment reports.

On the 2019 AAMC Medical School Graduation Questionnaire, nearly one-third of students reporting mistreatment rated their satisfaction with the outcome of the process as dissatisfied or very dissatisfied.6 Recent reports on incorporating restorative justice practices into medical school communities23 and recognizing exceptional teachers24 show promise, though further study of their effectiveness is needed.

We may also need to be better attuned to significant variation in the contextual components of various clinical clerkships, and how these may affect the nature of mistreatment across clerkships.8 For example, departments of surgery have made an effort to understand the perspectives of students, residents, and faculty, with regard to mistreatment.25-27 Surgery clerkships have offered targeted programs for students to understand the learning environment and share experiences in a safe setting and for residents to increase their awareness of mistreatment issues.27-29 As a result of these programs, students felt better able to handle mistreatment situations,29 student mistreatment reports decreased,28 and residents’ awareness of mistreatment improved.27

Though mistreatment is less likely to occur on family medicine clerkships,8-9 it still exists. In turn, FM clerkship directors must similarly take initiative to address the student mistreatment occurring on their clerkship at different preceptor sites. The practice environment of an office-based practice poses challenges to clinical teaching for both full-time faculty and community preceptors.12 FM clerkship directors may find it useful to first gain the perspectives of full-time faculty, community preceptors, and students on mistreatment. After gathering that information, possible interventions include helping students develop clear expectations of their role in caring for patients in the fast-paced office setting and assisting full-time faculty and community preceptors in creating a supportive learning environment for their students.

Our findings help to clarify current practices of FM clerkship directors in handling student mistreatment concerns. As there is a need to better handle student mistreatment issues nationwide,6 it is important for FM clerkship directors to proactively make efforts now to prevent student mistreatment on their clerkship. Further discussions of this issue at a national level, such as at Society of Teachers of Family Medicine meetings, may help FM clerkship directors start this important process and identify both research opportunities and best practices.

References

- Mavis B, Sousa A, Lipscomb W, Rappley MD. Learning about medical student mistreatment from responses to the medical school graduation questionnaire. Acad Med. 2014;89(5):705-711. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000199

- Heru A, Gagne G, Strong D. Medical student mistreatment results in symptoms of posttraumatic stress. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33(4):302-306. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.33.4.302

- Cook AF, Arora VM, Rasinski KA, Curlin FA, Yoon JD. The prevalence of medical student mistreatment and its association with burnout. Acad Med. 2014;89(5):749-754. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000204

- Hu YY, Ellis RJ, Hewitt DB, et al. Discrimination, Abuse, Harassment, and Burnout in Surgical Residency Training. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1741-1752. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1903759

- Mazer LM, Bereknyei Merrell S, Hasty BN, Stave C, Lau JN. Assessment of programs aimed to decrease or prevent mistreatment of medical trainees. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(3):e180870. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0870

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: 2019 All Schools Summary Report. July 2019. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2019-08/2019-gq-all-schools-summary-report.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2020.

- Fried JM, Vermillion M, Parker NH, Uijtdehaage S. Eradicating medical student mistreatment: a longitudinal study of one institution’s efforts. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1191-1198. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182625408

- Breed C, Skinner B, Purkiss J, et al. Clerkship-specific medical student mistreatment. Med Sci Educ. 2018;28(3):477-482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-018-0568-8

- Oser TK, Haidet P, Lewis PR, Mauger DT, Gingrich DL, Leong SL. Frequency and negative impact of medical student mistreatment based on specialty choice: a longitudinal study. Acad Med. 2014;89(5):755-761. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000207

- Schwiebert LP, Ramsey CN Jr, Davis A. Comparison of volunteer and full-time faculty performance in a required third-year family medicine clerkship. Teach Learn Med. 1992;4(4):225-232. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401339209539571

- Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance. CERA Family Medicine Clerkship Director Survey – 2018. https://www.stfm.org/publicationsresearch/cera/pasttopicsanddata/2018clerkshipdirectorssurvey/. Accessed March 6, 2020.

- Christner JG, Dallaghan GB, Briscoe G, et al. The community preceptor crisis: recruiting and retaining community-based faculty to teach medical students-a shared perspective from the Alliance for Clinical Education. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28(3):329-336. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2016.1152899 PMID:27092852

- Anthony D, Jerpbak CM, Margo KL, Power DV, Slatt LM, Tarn DM. Do we pay our community preceptors? Results from a CERA clerkship directors’ survey. Fam Med. 2014;46(3):167-173.

- Christner JG, Beck Dallaghan G, Briscoe G, et al. To pay or not to pay community preceptors? That is a question....... Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(3):279-287. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2018.1528156

- Shokar N, Bergus G, Bazemore A, et al. Calling all scholars to the council of academic family medicine educational research alliance (CERA). Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(4):372-373. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1283

- Brink D, Simpson D, Crouse B, Morzinski J, Bower D, Westra R. Teaching competencies for community preceptors. Fam Med. 2018;50(5):359-363. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2018.578747

- Huang WY, Dains JE, Monteiro FM, Rogers JC. Observations on the teaching and learning occurring in offices of community-based family and community medicine clerkship preceptors. Fam Med. 2004;36(2):131-136.

- Langlois JP, Thach SB. Bringing faculty development to community-based preceptors. Acad Med. 2003;78(2):150-155. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200302000-00009

- Drowos J, Baker S, Harrison SL, Minor S, Chessman AW, Baker D. Faculty development for medical school community-based faculty: a Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance study exploring institutional requirements and challenges. Acad Med. 2017;92(8):1175-1180. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001626

- Scott SM, Schifferdecker KE, Anthony D, et al. Contemporary teaching strategies of exemplary community preceptors—is technology helping? Fam Med. 2014;46(10):776-782.

- Latessa R, Keen S, Byerley J, et al. The North Carolina community preceptor experience: third study of trends over 12 years. Acad Med. 2019;94(5):715-722. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002571

- Minor S, Huffman M, Lewis PR, Kost A, Prunuske J. Community preceptor perspectives on recruitment and retention: The CoPPRR Study. Fam Med. 2019;51(5):389-398. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2019.937544

- Acosta D, Karp DR. Restorative justice as the Rx for mistreatment in academic medicine: applications to consider for learners, faculty, and staff. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):354-356. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002037

- Blackall GF, Wolpaw T, Shapiro D. The exceptional teacher initiative: finding a silver lining in addressing medical student mistreatment. Acad Med. 2019;94(7):992-995. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002700

- Castillo-Angeles M, Watkins AA, Acosta D, et al. Mistreatment and the learning environment for medical students on general surgery clerkship rotations: what do key stakeholders think? Am J Surg. 2017;213(2):307-312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.10.013

- Castillo-Angeles M, Calvillo-Ortiz R, Barrows C, Chaikof EL, Kent TS. The learning environment in surgery clerkship: what are faculty perceptions? J Surg Educ. 2020;77(1):61-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.07.003

- Castillo-Angeles M, Calvillo-Ortiz R, Acosta D, et al. Mistreatment and the learning environment: a mixed methods approach to assess knowledge and raise awareness amongst residents. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(2):305-314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.07.019

- Lau JN, Mazer LM, Liebert CA, Bereknyei Merrell S, Lin DT, Harris I. A mixed-methods analysis of a novel mistreatment program for the surgery core clerkship. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):1028-1034. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001575

- Hasty BN, Miller SE, Bereknyei Merrell S, Lin DT, Shipper ES, Lau JN. Medical student perceptions of a mistreatment program during the surgery clerkship. Am J Surg. 2018;215(4):761-766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.01.001

There are no comments for this article.