A looming shortage of rural physicians compounds the existing health care challenges that rural patients face.1,2 Understanding the perspective of rural residents and including their voices in the design process is an essential element when planning patient-centered solutions to improve health outcomes in rural communities.3 Creating effective health policy that matters to residents of rural communities requires scientific data, yet little evidence exists in medical literature describing the attitudes of rural residents about the impact of losing their local physician.4-7 This exploratory study investigated how rural community members experience the loss of their physician and examined types of person-defined value that rural family physicians bring to their communities. This information can be helpful for educators of medical trainees interested in rural practice to gain a deeper understanding about the nature of relationships and community engagement that is most meaningful to their future patients.

BRIEF REPORTS

What Is the Impact on Rural Area Residents When the Local Physician Leaves?

Paulius Mui | Martha M. Gonzalez | Rebecca Etz, PhD

Fam Med. 2020;52(5):352-356.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2020.337280

Background and Objectives: Scarce evidence exists in the medical literature describing the attitudes of rural community residents about the impact of losing their local physician. This pilot study explores aspects of access to care, both within and outside of primary care settings, that result from loss of a rural family physician.

Methods: We selected study participants through convenience and snowball sampling, and we conducted in-person interviews of up to 60 minutes. We audio recorded and transcribed the interviews (May to August, 2018), then analyzed transcripts using immersion crystallization and managed within Atlas.ti 7.0 software (Berlin, Germany).

Results: We interviewed 18 participants, some of whom interviewed as pairs. Our analysis revealed three significant themes: rurally-specific access to care concerns, relationships valued for being both community and care based, and loss felt specific to the integrated community leadership roles occupied by family physicians. In addition, participants identified social challenges they associated with losing their “country doctor,” such as withering community cohesion.

Conclusions: Our findings suggest that rural physicians offer tremendous value to their communities, both inside and beyond their clinic walls. Issues of social cohesion and local health leadership affected by physician loss should be addressed by policy makers and educators charged with designing patient-centered solutions to improve health outcomes in rural communities. Current health and medical education reforms would benefit from greater focused attention on these issues.

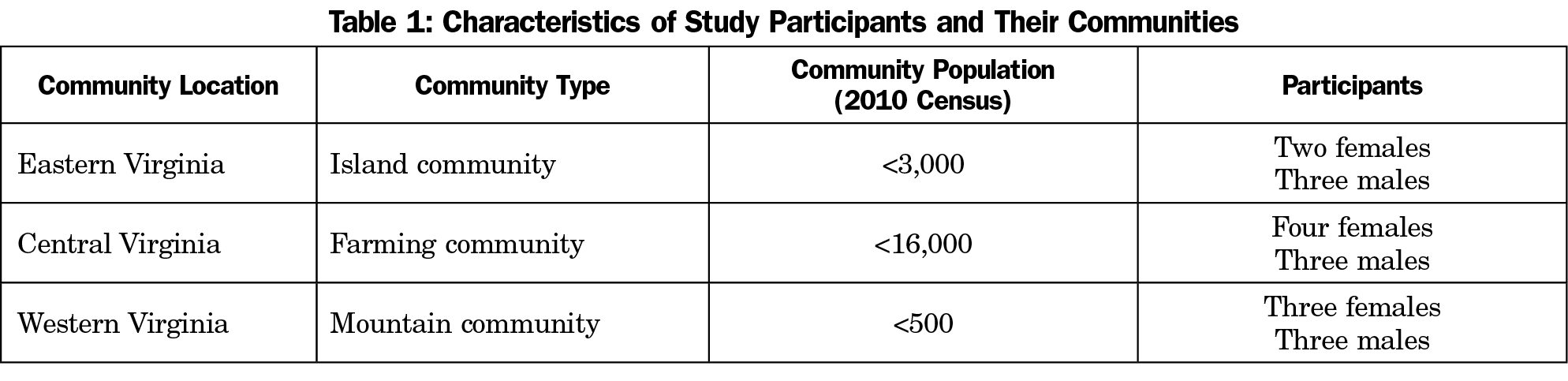

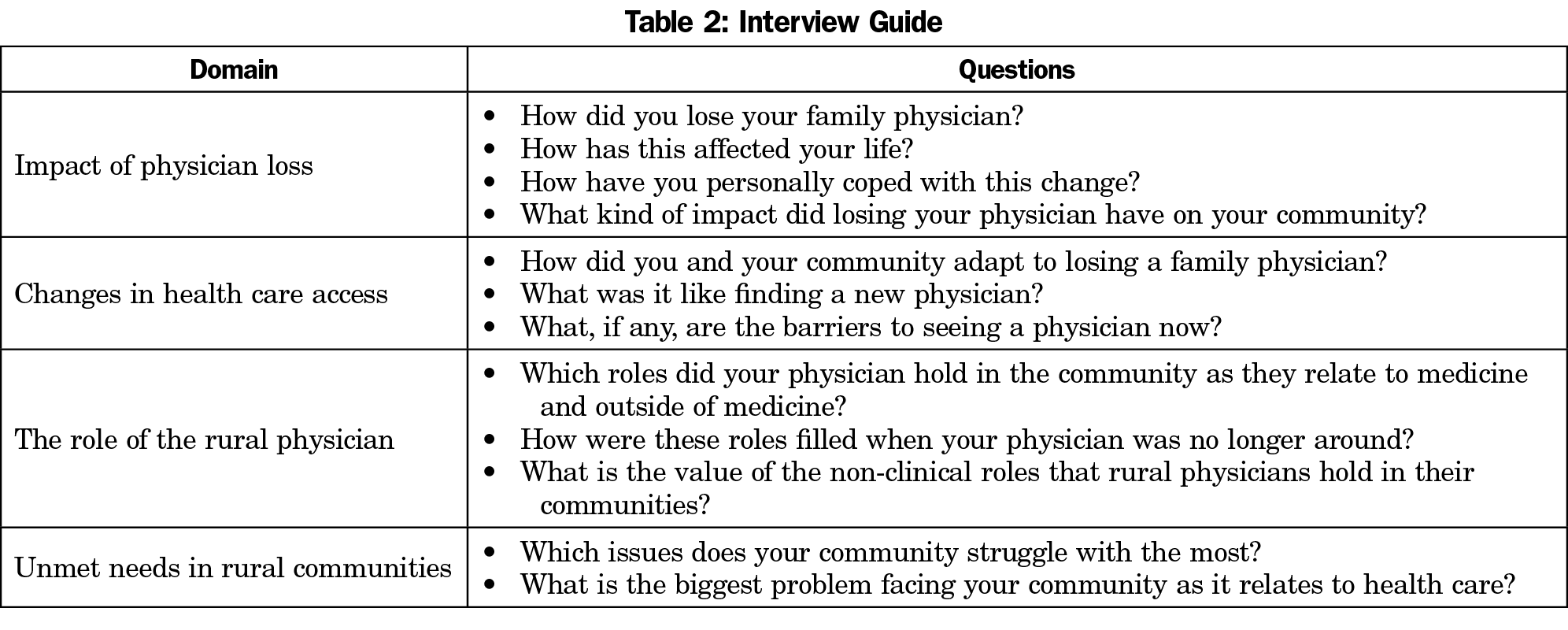

We selected participants through convenience and snowball sampling. Family physicians among several Virginia-based professional networks identified potential participants. Participants were eligible if they (1) lived in a rural area, and (2) had experienced the loss of their local family physician in the last 5 years. As an exploratory study, inclusion of participants was not limited or directed by a need for diversity of participant social/demographic characteristics. As a result of snowball sampling, potential participants were often long-time area residents of mature age and similar (Caucasian) demographic (Table 1). Participants were consented, received written information, and agreed to an in-person interview. Interviews included 12 open-ended questions in the following domains: impact of physician loss, changes in health care access, the role of the rural physician, and unmet needs in rural communities. The interview guide, including domains and sample wording of interview questions, is included in Table 2. The wording of interview questions as fielded included minor variability in order to maintain a conversational feel to the interview.

We audio-recorded, transcribed, and then coded interviews using an immersion crystallization approach in which data were read and reread in structured cycles.8 We added codes to the codebook until saturation was reached, ie, until no new information or themes emerged during data analysis. Based on the guidance of previous research, a sample size of five to eight participants should be sufficient to reach saturation of findings.9 Though our final sample included 18 individuals, the additional sample size did not appear to expand the number or significance of themes identified. After establishing a codebook among research team members, the data were coded independently, merged, and discussed. Discrepancies among coders were resolved through consensus. The Institutional Review Board of Virginia Commonwealth University approved this study.

We recruited and interviewed 18 participants from three geographically distinct areas of Virginia. Some were interviewed in pairs (Table 2). In some cases, we applied minor edits to participant quotations to adjust for readability.

The presentation of our results is organized around three main themes that emerged through analysis: rurally-specific access to care concerns, relationships valued for being both community and care based, and loss felt specific to the integrated community leadership roles occupied by family physicians. These themes are summarized below. Themes are reported if they were found among more than half of study participants. Supporting quotations are found in Table 3.

Rural Access to Care: Transportation, Preventive Care, Changing Health Care Paradigm

Participants without physical proximity to a physician had difficulty getting timely care due to transportation issues. In geographically isolated communities, people who drove spoke about limitations related to cost of gas and weather conditions, particularly in mountain areas. Others did not have a way to leave town or were not used to leaving their community. When an area physician was lost, the inability to see a physician locally placed stress on families caring for their elderly members and led to unrealized preventive health opportunities by those without a support system. Some participants ultimately sought medical care from another nearby physician, while others had no physician left in their community and either traveled outside of their community to receive medical care or chose to forego primary care.

Participants also discussed their experience with the presently changing health care system. They juxtaposed attentive house calls and the flexible availability of previous local physicians with the inability of current medical providers to accommodate their needs. They described the present health care paradigm as rigid and impersonal (ie, nonrelational).

Community/Care-based Relationships: Familiarity and the Country Doctor Persona

When a rural community loses its physician, a strong familiarity resulting from years of history between patients and their doctor also disappears. Participants missed having a local physician who knew them outside of their medical concerns. Participants who were fortunate to find a replacement doctor often found that the replacement did not live locally. They equated this lack of locality with a lost sense of familiarity and closeness they previously enjoyed.

Many participants said their new physicians did not have the “country doctor” persona they were used to experiencing. They described their previous physician as someone who was “used to country people,” and reminisced “if you couldn’t make it to the office, he would come to you.” There was a “knowing” they missed, born of familiarity with the rural lifestyle. New patient-doctor relationships were tense, formal, and seemed based on difference, rather than sameness.

Loss of Integrated Health Leaders: Community and Civic Engagement

Many participants noted the practice setting of their old country doctor contributed to their sense of feeling socially connected, not just with the doctor but with one another. Community members enjoyed running into each other and catching up with their neighbors in the waiting room. Having this type of a shared space made residents feel closer to one another, and was identified as noticeably absent by participants who lived in towns as yet unable to find a replacement physician.

Participants also described their physicians’ deep involvement in community affairs. Collectively, their physicians touched many spheres of civic engagement. They organized health talks and wellness walks, volunteered at the food pantry, served on the emergency medical services crew, attended church activities, and participated in music concerts and art shows. These are social and health leadership roles in which participants were used to seeing their physician, a leadership role that fragmented on the physician’s departure, leading to a sense of lost community cohesion among allied health services.

Understanding how rural communities are affected by the loss of their local physicians is imperative for creating informed policies to bridge gaps in care and social cohesion, and to improve the health care experience of patients by focusing on issues that matter most to them.

While access to care, relationships with physicians, and community engagement are relevant to all patients, health care policy makers would be advantaged by focused attention to the unique needs and place-based perspectives found among the 60 million Americans currently living in rural communities. For example, we learned that while physical proximity to a physician is important to ensure timely preventive care, having a deep emotional connection to the doctor was felt to be paramount. Patients from rural areas yearn for a bond of familiarity, geniality, and informality that has been replaced by sterility of the present-day health care system.

These findings are particularly relevant for educators and mentors of medical trainees. To address the needs of rural communities, selecting medical school applicants who align culturally with values of their future patients has the potential to make a positive difference. This is especially important in the context of a recent study documenting a 15-year decline in rural medical student enrollment.10 Training of future rural physicians would be improved if it included curricula responsive to experiential issues identified as most important to rural patients, such as the themes noted above. Furthermore, community compatibility has been shown to be an important factor in physician recruitment and retention in rural areas. Thus, creating clinical opportunities in rural areas can be invaluable for nurturing medical students and residents who might choose to practice in these communities.11

It is evident that rural physicians offer tremendous value to their communities, both inside and beyond the clinic walls. Themes from our interviews highlight issues related to physician loss that deserve further investigation. Rural physicians have the potential to positively impact their communities along many dimensions and to serve as a catalyst to keep community members engaged in daily life. Our study highlights some of the qualities and the depth of community engagement that might be important to rural area residents. Our findings can inspire young clinicians to consider a career in rural medicine and the varied opportunities for health leadership found in small communities.

Limitations

Although this study identifies several meaningful avenues for future research, its implications are limited due to small sample size and potentially biased sampling through referrals. Study participants were relatively homogeneous in age and ethnicity with unknown variation in educational or economic background. These social demographics are known to significantly influence experience of care delivery. Having identified common themes through this exploratory study, future research should include purposive sampling and sample sizes sufficient for investigating how themes might vary based on common demographic stratifications. While our findings are significant in the ways in which they identify areas lacking current research, the limited variability in demographics among participants limit their current generalizability to all rural communities or residents.

It is essential to incorporate the voices of rural community members when designing health policy solutions to address their unmet health care needs. Further study is required to investigate how rural communities are experiencing and dealing with physician loss in other regions of the United States.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: A Microresearch Award from Rural Primary care, Research, Education and Practice (Rural PREP) funded this study.

Presentations: Preliminary findings of this study were presented at National Organization of State Offices of Rural Health, Regional Meeting, Charlottesville, Virginia in June 2018.

References

- Ricketts TC. The migration of physicians and the local supply of practitioners: a five-year comparison. Acad Med. 2013;88(12):1913-1918. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000012

- Streeter RA, Zangaro GA, Chattopadhyay A. Perspectives: using results from HRSA’s Health Workforce Simulation Model to examine the geography of primary care. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(suppl 1):481-507. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12663

- Levy M, Holmes C, Mendenhall A, Grube W. Engaging rural residents in patient-centered health care research. Patient Exp J. 2017;4(1):46-53. https://doi.org/10.35680/2372-0247.1164

- Biola H, Pathman DE. Are there enough doctors in my rural community? Perceptions of the local physician supply. J Rural Health. 2009;25(2):115-123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00207.x

- Muus KJ, Ludtke RL, Gibbens B. Community perceptions of rural hospital closure. J Community Health. 1995;20(1):65-73. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02260496

- Reif SS, DesHarnais S, Bernard S. Community perceptions of the effects of rural hospital closure on access to care. J Rural Health. 1999;15(2):202-209. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.1999.tb00740.x

- Brownson RC, Chriqui JF, Stamatakis KA. Understanding evidence-based public health policy. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(9):1576-1583. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.156224

- Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Qualitative analysis: how to begin making sense. Fam Pract Res J. 1994;14(3):289-297.

- Kuzel AJ. Sampling in Qualitative Inquiry. In: Crabtrree BF, Miller WL, eds. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999:33-45.

- Shipman SA, Wendling A, Jones KC, Kovar-Gough I, Orlowski JM, Phillips J. The Decline In Rural Medical Students: A Growing Gap In Geographic Diversity Threatens The Rural Physician Workforce. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(12):2011-2018. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00924

- Paladine HL, Hustedde C, Wendling A, et al. The role of rural communities in the recruitment and retention of women physicians. Women Health. 2020;60(1):113-122. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2019.1607801

Lead Author

Paulius Mui

Affiliations: Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, Richmond, VA

Co-Authors

Martha M. Gonzalez - Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine and Population Health, Richmond, VA

Rebecca Etz, PhD - Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, Richmond, VA

Corresponding Author

Paulius Mui

Email: muip@vcu.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.