Background and Objectives: The management of chronic pain is an important topic for training competent family physicians. The purpose of this study was to determine factors in teaching about chronic pain and whether state overdose death rates were associated with teaching chronic pain topics.

Methods: Data were collected as part of the 2019 Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) Clerkship Directors’ Survey. The response rate was 71%. Respondents answered questions about the amount of time spent teaching about chronic pain diagnoses, approach to chronic pain, opioid medications, nonopioid medications and nonpharmacologic treatments for chronic pain.

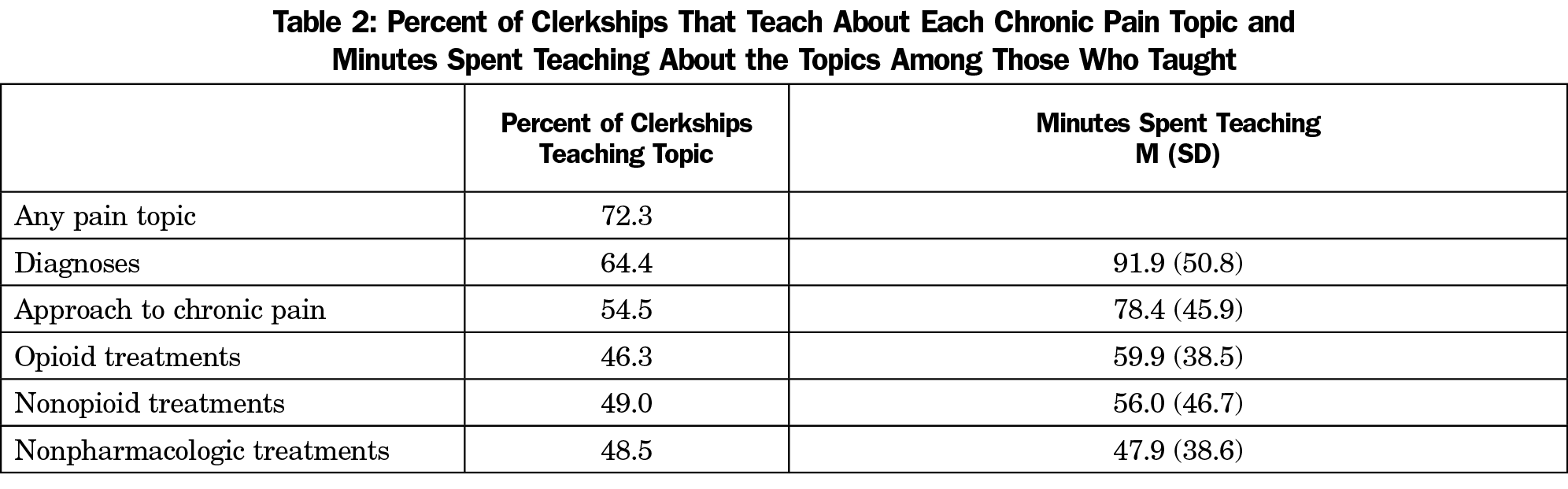

Results: The most frequent topic was chronic pain diagnoses, taught by 64% of clerkships with an average of 92 minutes spent on the topic. Each chronic pain topic was taught by nearly 50% of clerkships, and 72.3% of clerkships taught at least one topic. More clerkships were teaching about opioids, nonopioids, and nonpharmacological treatments for chronic pain than in 2014. Time currently spent teaching about opioids was positively correlated with clerkships’ state 2014 drug overdose death rate.

Conclusions: The majority of family medicine clerkships teach about chronic pain, and the amount of time dedicated to this topic has increased over the last 5 years. A state’s opioid overdose rate correlates with the amount of time spent teaching about opioids, but does not correlate with the amount of time teaching about other chronic pain subtopics. It is possible that the opioid crisis is causing a shift in the subtopics of chronic pain teaching.

The management of chronic pain is an important topic for training competent family physicians.1 The majority of chronic pain patients are treated by primary care physicians,2 and family physicians are well-suited to address multiple dimensions of a pain patient’s care.3 Current guidelines strongly emphasize an interdisciplinary, multimodal approach to treatment.4 However, most primary care physicians feel poorly prepared to take on this problem.5,6

Given the importance of chronic pain and the natural fit with primary care, it is important to understand factors influencing whether clerkship directors teach chronic pain management during the clerkship. A 2014 CERA survey7 revealed that half of all family medicine clerkship directors reported they were not teaching about chronic pain at all. The intervening 5 years have seen a tremendous increase in the attention toward chronic pain and the opioid epidemic.8 However, training about opioid management and addiction is very different from education about chronic pain, and may even be pushing chronic pain education to the sidelines.9

In this study, we examined factors associated with teaching about chronic pain topics and whether teaching about opioid, nonopioid, and nonpharmacological treatments for chronic pain has increased in the last 5 years.

Data were gathered as part of the 2019 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine clerkship directors.10 We emailed the survey to 126 US and 16 Canadian family medicine clerkship directors between June 19, 2019 and August 2, 2019 with a personalized greeting and a letter signed by the presidents of each of the four sponsoring organizations with a link to the survey (conducted via SurveyMonkey). We sent four reminders to nonresponders. The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved the study in June 2019.

Survey Questions

Clerkship directors answered questions about themselves, their medical schools, their clerkships, and the amount of time spent teaching chronic pain diagnoses (such as chronic low back pain, fibromyalgia, chronic headache, neuropathy, chronic joint pain, etc); approach to chronic pain (such as chronic pain assessment, pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic management of chronic pain, chronic pain as a neurological phenomenon, biopsychosocial model, etc); and opioid, nonopioid, and nonpharmacologic treatments for chronic pain. We asked if the time teaching about chronic pain increased in the last 5 years and whether chronic pain should be taught using a multimodal, interprofessional approach.

Analyses

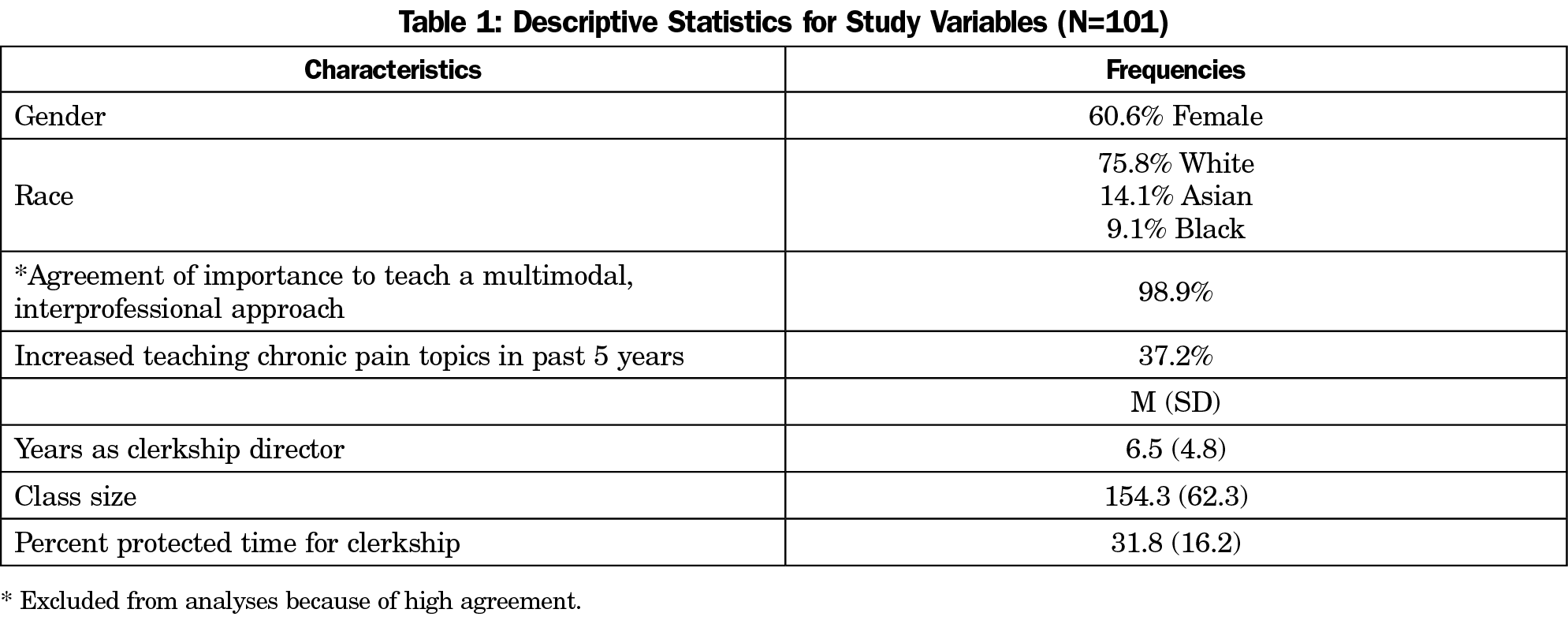

Descriptive statistics summarized characteristics of clerkship directors, their schools, their clerkships, minutes teaching chronic pain topics, whether time spent teaching increased in the past 5 years, and whether chronic pain should be taught using a multimodal, interprofessional approach. Z scores were computed for time teaching about diagnoses, approaches to pain management, opioids, nonopioids, and nonpharmacologic pain management. We removed outliers for analyses if they were more than 2.5 standard deviations from the mean. Bivariate correlations determined associated between drug overdose death rates (from the CDC) and the amount of time teaching about the chronic pain topics.

The overall response rate was 71% (101/142). Descriptive statistics for study variables are summarized in Table 1. The most frequent topic taught was chronic pain diagnoses with clerkships spending an average of 91.9 minutes teaching the topic. Each chronic pain topic was taught by nearly 50% of clerkships, with 72.3% of clerkships teaching at least one topic (Table 2).

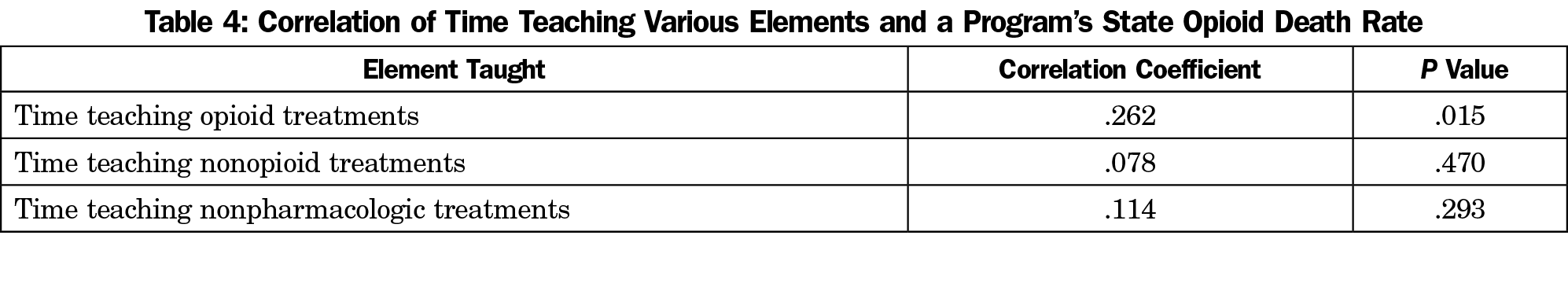

In 2019, more clerkships were teaching about opioids, nonopioids, and nonpharmacological treatments for chronic pain than were in 2014 (Table 3). We found a positive correlation between a clerkship’s state drug overdose death rate in 2014 and time currently spent teaching about opioids. No correlations were found for time teaching about nonopioid and nonpharmacological treatments. The Canadian clerkships were not included in these analyses because we did not have overdose death rates for the provinces from 2014 (Table 4).

In contrast to our 2014 findings, the majority of family medicine clerkships are now teaching one or more chronic pain topics, with 37% of clerkships reporting increased time teaching chronic pain topics from 5 years ago. Clerkships have increased the amount of time spent teaching about opioids, nonopiods, and nonpharmacologic treatments. As medical professionals have sought to relieve suffering through greater use of opioids, a tragic complication has emerged. There is increasing awareness of opioid overprescribing and abuse as a public health crisis, leading to an unprecedented number of opioid-related deaths.11 Medical schools have identified a need for better pain-related education, including education about opioids and nonopioid treatments.12 The emergence of a multifaceted approach to chronic pain in the family medicine clerkship may be a reflection of the conflicting realities of an urgent need to treat pain and a devastating opioid crisis. Nearly all clerkship directors agreed that a multimodal approach to chronic pain is ideal.

We hypothesized that a state’s drug overdose death would relate to amount of time teaching about chronic pain management. We chose an overdose death rate that coincided with our previous survey in 20147 and because it may take a few years for recognition of an epidemic and subsequent curriculum change. We found that current teaching about opioids did correlate with 2014 state opioid death rate. It is plausible that clerkships in states with the highest death rates would be most likely to dedicate curricular time to opioids specifically.

Our study had several limitations. We chose to exclude outliers from analyses who were 2.5 standard deviations from the mean for time teaching chronic pain topics. We assumed teaching more than 3 hours on a single topic was an error. We acknowledge this study only quantifies time spent teaching about chronic pain during the family medicine clerkship. Time in other courses, including team-based learning, longitudinal courses or fourth-year courses was not captured by this survey.

Although more clerkship directors are now teaching about chronic pain, many still are not. We demonstrated a correlation between a state’s opioid death rate and time spent teaching about opioids (and no correlation with time spent on other aspects of chronic pain management). It is important not to let the opioid crisis shift our chronic pain teaching to become focused primarily on opioid use.

References

- St Sauver JL, Warner DO, Yawn BP, et al. Why patients visit their doctors: assessing the most prevalent conditions in a defined American population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(1):56-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.08.020

- Breuer B, Cruciani R, Portenoy RK. Pain management by primary care physicians, pain physicians, chiropractors, and acupuncturists: a national survey. South Med J. 2010;103(8):738-747. https://doi.org/10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181e74ede

- Klinar I, Ferhatovic L, Banozic A, et al. Physicians’ attitudes about interprofessional treatment of chronic pain: family physicians are considered the most important collaborators. Scand J Caring Sci. 2013;27(2):303-310. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01039.x

- Dale R, Stacey B. Multimodal treatment of chronic pain. Med Clin North Am. 2016;100(1):55-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2015.08.012

- Upshur CC, Luckmann RS, Savageau JA. Primary care provider concerns about management of chronic pain in community clinic populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):652-655. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00412.x

- Yanni LM, McKinney-Ketchum JL, Harrington SB, et al. Preparation, confidence, and attitudes about chronic noncancer pain in graduate medical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(2):260-268. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-10-00006.1

- Schiel Zoberi K, Everard KM, Antoun J. Teaching chronic pain in the family medicine clerkship: influences of experience and beliefs about treatment effectiveness: a CERA study. Fam Med. 2016;48(5):353-358.

- Ballantyne JC. Opioids for the treatment of chronic pain: mistakes made, lessons learned, and future directions. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1769-1778. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002500

- Loeser JD, Schatman ME. Chronic pain management in medical education: a disastrous omission. Postgrad Med. 2017;129(3):332-335. https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.2017.1297668

- Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW. Creating a gentralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257-260. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2228

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Opioid Overdose Crisis. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-overdose-crisis#one. Revised Janury 2019. Accessed October 13, 2019.

- Tellier PP, Bélanger E, Rodríguez C, Ware MA, Posel N. Improving undergraduate medical education about pain assessment and management: a qualitative descriptive study of stakeholders’ perceptions. Pain Res Manag. 2013;18(5):259-265. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/920961

There are no comments for this article.