Abstract: Clinical educators are continually seeking innovative methods and settings for teaching. As such, they have increasingly begun to use art museums as a new educational space in which to build clinically-relevant skills and promote learners’ professional identity formation. Art museum-based pedagogy can be understood through the framework of transformative learning theory, which provides an account of how adults learn through experience. In this article, the authors apply this theory to art museum-based teaching and offer a practical overview of art museum-based activities, highlighting three exemplars: visual thinking strategies, personal responses tour, and group poems. This toolbox of art museum-based teaching methods provides a launching pad for educators and learners to explore this innovative educational strategy.

Clinical educators must ensure that health professions learners develop the knowledge, skills, behaviors, and attitudes to practice independently amidst the numerous, unpredictable challenges of the health care environment. A growing body of evidence suggests that an equally important educational responsibility is the support of professional identity formation (PIF),1-3 allowing learners to “think, act, and feel” like competent health care professionals.4 Integrating the arts and humanities into health professions education (HPE) may enhance positive PIF among health professions learners and practitioners5 while improving clinical skills6-9 and increasing joy and renewal.10, 11 Accordingly the Association of American Medical Colleges has established a multiphase initiative, The Role of Arts & Humanities in Physician Development: From Fun to Fundamental.12 Most HPE research on the use of arts and humanities to support PIF examines methods implemented in classroom and clinical settings. Art museums are an innovative HPE space that may be particularly well-suited for promoting PIF by virtue of providing opportunities for fresh perspectives and new insights.

Art museum-based education represents a model case for transformative learning. The museum represents a new and creative environment for HPE that is physically distinct from usual teaching settings, offering a potentially stimulating space for students to learn. For some learners, the art museum is a place both unfamiliar, full of ancient art from different cultures, and familiar, sparking associations with one’s own experiences. For these learners, the art and space itself may invoke welcome feelings of introspection, reflection, and connection with others across time, space, and culture. Other learners may experience the art museum entirely differently. For them, the museum may be boring, stodgy, or daunting (although the same might be said about medical school classrooms). It can elicit unexpected emotions and memories. It can surprise and provoke. It thus offers a unique setting for PIF and skills formations.5, 7-9, 13, 14

Art museum-based education can enhance close observation/discrimination7, 15, 16 and communication/collaboration skills integral to clinical practice.9, 15, 17, 18 These teaching methods can also promote critical thinking by enhancing students’ and teachers’ ability to observe, use evidence, speculate, and evaluate or revise ideas.19-21 More generally, arts-based teaching promotes a growth mindset by encouraging learners to embrace intellectual curiosity, perseverance, and tolerance of ambiguity.19, 20 With skillful facilitation, these methods enable health care professionals to express their vulnerabilities and insecurities, and support self-care. It is the combination of the museum space itself—often quiet, spacious, filled with natural light, and away from classrooms and clinical settings—and the art within the space that makes this learning environment special. While not everyone may have access to a local art museum and the associated educational resources due to geographic or other reasons (eg, a pandemic like COVID-19), art museum-based methods can be delivered in settings outside the museum, including online. Online art museum-based teaching allows access to nearly unlimited virtual collections of images and enables learners to reflect and engage from a location of their choosing.

Because art museum-based education is an emerging field with a relatively sparse literature, many health professions educators may be unfamiliar with its theoretical underpinnings and methods. This article provides a roadmap for using the art museum to promote transformational learning in the health professions.

Although a growing body of evidence supports the use of art museum-based teaching, further research and critical analyses are needed to better understand its theoretical underpinnings and most effective application in HPE. Educational pioneer John Dewey warned that, without appropriate reflection on core educational values, systems are vulnerable to teaching fads.22 It is important to consider each pedagogical practice in the context of a grounding educational theory to understand the effects that novel methods may have on outcomes relating to learner cognition and professional development.

As initially posited by Jack Mezirow, TLT describes how adults use their experiences to construct meaning and make sense of the world, and thus more easily handle similar situations in the future.23 Learners may sometimes encounter a situation so unfamiliar and challenging that it alters their existing understanding of the world.23 Mezirow refers to these situations as “disorienting dilemmas” and suggests they are necessary, but not sufficient to prompt true learning23 and transformation.24 In order for these to occur, learners must also engage in critical reflection of their own underlying cognitive and affective perspectives, a process that occurs most effectively when learners can discuss ideas with one other.25-27

Tebogo Tsimane and Charlene Downing operationalize Mezirow’s model into three elements: (1) antecedents, (2) processes and procedure, and (3) outcomes.28 Antecedents refer to preexisting cognitive and affective perspectives. The transformative learning process can be triggered by an uncomfortable situation that, coupled with reflection and discussion, prompts learners to question these perspectives. The resulting change in perspective is classified as an outcome of the transformation.

For health professions learners who are more familiar with classrooms and clinics than art museums, art and the museum itself provide disorienting dilemmas that may trigger transformation. The interactive and group-based activities, and the interactive nature of art museum-based teaching further promote the critical reflection and discourse necessary for growth. Through individual and group exercises designed to promote reflection, learners can begin to question some of their previously established cognitive and affective perspectives. They can be inspired to create and test alternative world views, a phenomenon that can lead to transformation.

When developing growth-promoting experiences, educators should consider multiple curricular goals. They must assess the needs of each learner and encourage learners to define and evaluate specific learning goals. Experiences should promote a collaborative problem-solving approach within a supportive learning environment. Teaching methods should also foster experiential and participatory engagement of learners.29

In contrast to the traditional delivery of learning objectives at the beginning of educational activities, art museum-based teaching typically involves minimal up-front instruction. This is intentional to create the disorienting dilemma necessary for transformative learning. Encouraging learners to embrace the unfamiliar and address ambiguity can enhance their ability to grow and change.

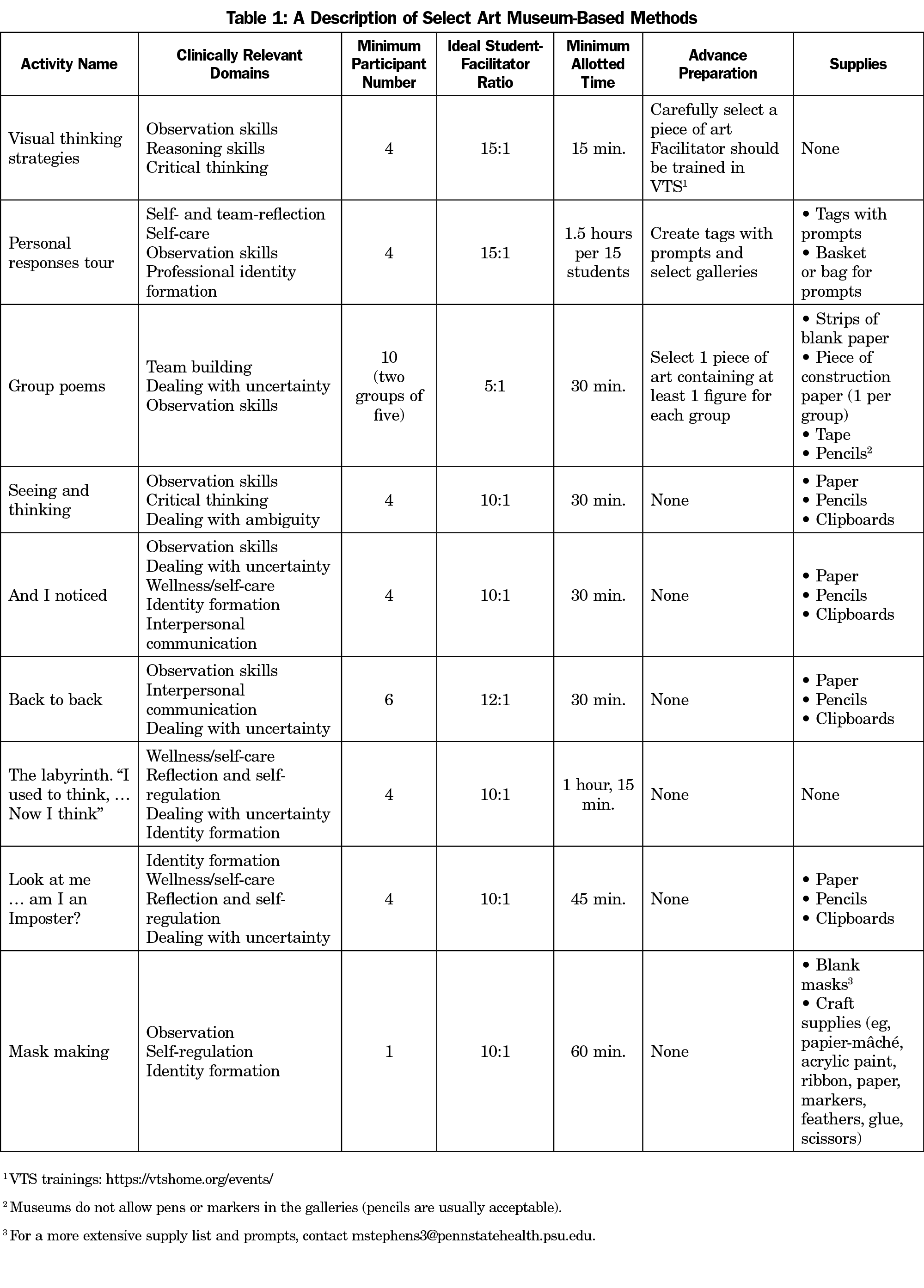

Most art museum-based activities involve small groups of learners, ideally led by a health professions educator and museum educator dyad (Table 1). After each activity, one or both of these leaders guide learners through a debriefing to discuss their perceptions of the activity and share in a group reflective process. This post hoc analytic process promotes learner autonomy, reinforces key principles, and validates the importance of multiple perspectives when approaching ambiguous problems commonly seen in clinical care.

Mezirow suggests that transformation can occur after a single experience or through multiple experiences.23 Educators designing and leading art museum-based longitudinal curricula need not feel pressured to ensure that every activity is emotionally charged and/or otherwise disorienting. With adequate time for iterative exposure, a curriculum can begin with simple experiences to develop learners’ comfort with the art museum setting and then gradually incorporate more challenging or provoking scenarios.

The art museum offers many ways for health professions learners to engage in reflective, growth-promoting experiences (Table 1). Visual thinking strategies (VTS), the personal responses tour (PRT), and group poems are among the most widely used art museum-based teaching tools and exemplify how art museum-based methods can be used in HPE.

Visual Thinking Strategies

VTS is an approach that facilitates open-ended group discussions about art. VTS is the most widely used and studied art museum-based pedagogical method in HPE. In VTS, participants view and discuss works of art together, prompted by questions that support responses grounded in close looking and that hold the group in shared inquiry. Although all art is ambiguous at some level (because the viewer can never be exactly certain as to what the artist intended), the art selected for VTS needs to contain enough ambiguity to promote differing interpretations during the discussion, thereby creating a slightly disorienting dilemma. The facilitator leads the group using the three basic questions “What’s going on in this picture?” “What do you see that makes you say that?” and “What more can we find?”30 Additionally, the facilitator points to what is being described and paraphrases and links learners’ responses. Although VTS may sound simple, expert VTS facilitation often requires years of specialty training and practice.

VTS was originally designed to promote the aesthetic development (ie, understanding when looking at art) of K-12 learners, but teachers began to notice their learners applied the critical thinking strategies learned in VTS to other, nonart subjects.30 This prompted VTS developers Abigail Housen and Philip Yenawine to conduct a longitudinal controlled trial of VTS’ effect on critical thinking and its transfer among early learners; results suggested that VTS improves critical thinking skills that transfer to different subject domains30

VTS has been used and studied with a variety of health professions learners, including undergraduate and graduate medical trainees, as well as nursing learners.31, 32 Most of the published studies on VTS in health professions learners are single-site descriptions of cross-sectional outcomes based on learner self-reports and lack a comparison group, limiting the conclusions that can be drawn from the evidence.9,13,15,33

Personal Responses Tour

In a PRT, participants individually explore a set of galleries in the art museum in search of a work of art that responds to a unique prompt. After independently reflecting on the connection between the art and the prompt, participants then reconvene to tour the galleries together, sharing their selections, prompts, and reflections with one other.34,35 Prompts can be drawn from the literature34, 35 or facilitators can create unique prompts to match specific learners and/or curricular needs. PRT invites learners to personally reflect on the relationship between a work of art and a prompt—an atypical cognitive task in HPE.

PRT has not been evaluated as extensively as VTS. One small study of medical students and residents suggests that PRT promotes community building, empathic listening, and appreciation of multiple perspectives. PRT also offers a reprieve from busy clinical work, promoting renewal and personal reflection.34 However, much more work needs to be done to assess the impact of PRT on learner outcomes, before drawing any definitive conclusions about its utility in HPE.

Group Poems

In contrast to the previous two examples, the group poem activity involves an act of art creation. In this activity, teams are divided into small groups to work together to create a written work based on a shared visual and spoken prompt. Each small group is assigned to review a different preselected work of art that depicts at least one figure. After examining the assigned artwork, participants are asked to write down a phrase that they imagine a figure in the artwork might be saying. Each participant reads their phrase aloud to the group. Together, the group then sequences all of the phrases into a collective poem, which is then shared with the other group(s). Participants often realize both the differences in perspectives represented by the variation in phrases within the group and that there is no right way to assemble the poem. For some, understanding how their peers interpret a work of art differently can transform how they view the art, creating the type of unusual experience that may spark growth. To the authors’ knowledge, an evaluation of this art museum-based activity has not been reported in the literature. However, this teaching tool could potentially enhance several clinically relevant skills, including close observation, communication, empathy, and teamwork.

Health professions educators are discovering how the art museum can be a setting for learners to build clinical skills and engage in critical reflection and discussion on matters relevant to life in medicine. Art museum-based teaching methods can be developed and adjusted for learners at any level of training. A major potential benefit of art museum-based HPE is that the museum can provide the time and space away from clinical demands that many learners need to engage in reflection and meaningful dialogue. The museum and its art can support many learners who seek to reconnect with themselves and their core values. As the concept of transformation and its core components are defined in ways that are more concrete and measurable, the ability for HPE researchers to examine the mechanisms by which art museum-based teaching may support transformative learning will expand, as will the opportunity to more rigorously evaluate any impact of this pedagogy on learners.

Art museum-based education is an emerging field with a relatively sparse literature, thus many health professions educators may be unfamiliar with its theoretical underpinnings and methods. In this article, we described TLT and suggested a rationale for grounding art museum-based pedagogical methods in this theoretical foundation. We provided a road map and toolbox of activities to guide and support educators in the use of art museums for transformative learning. We presented these resources in the context of the growing body of literature and increasing institutional attention on the role of the arts and humanities in HPE, that we hope will pique interest in this exciting field and encourage health professions educators to try some of these teaching methods.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Cambridge Health Alliance Center for Professional and Academic Development and the Harvard Macy Institute’s Art Museum-Based Health Professions Educators Fellowship and its faculty team including museum educators Corinne Zimmermann and Ray Williams and medical educators Liz Gaufberg and Lisa Wong. The authors also thank Elizabeth Ryznar, Scott Wright, and Philip Yenawine for their comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of the manuscript.

Financial Support: Dr Chisolm is the Director of the Paul McHugh Program for Human Flourishing, through which her work is supported.

References

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements Section VI With Background and Intent. 2017. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_Section%20VI_with-Background-and-Intent_2017-01.pdf. Accessed January 16, 2019. pp. 8,10.

- Lebensohn P, Dodds S, Benn R, et al. Resident wellness behaviors: relationship to stress, depression, and burnout. Fam Med. 2013;45(8):541-549.

- Reed S, Kemper KJ, Schwartz A, et al. Variability of burnout and stress measures in pediatric residents: an exploratory single-center study from the pediatric resident burnout-resilience study consortium. J Evid Based Integr Med. 2018;23:2515690X18804779.

- Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, et al. Special report: suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2011;146(1):54-62. doi:10.1001/archsurg.2010.292

- Lebares CC, Guvva EV, Ascher NL, O’Sullivan PS, Harris HW, Epel ES. Burnout and stress among US surgery residents: psychological distress and resilience. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(1):80-90. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.10.010

- de Oliveira GS Jr, Chang R, Fitzgerald PC, et al. The prevalence of burnout and depression and their association with adherence to safety and practice standards: a survey of United States anesthesiology trainees. Anesth Analg. 2013;117(1):182-193. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182917da9

- Tawfik DS, Profit J, Morgenthaler TI, et al. Physician burnout, well-being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(11):1571-1580. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.05.014

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-576. doi:10.1370/afm.1713

- Schaufeli Wilmar B, Leiter Michael P, Maslach C. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Dev Int. 2009;14(3):204-220. doi:10.1108/13620430910966406

- Bianchi R, Schonfeld IS, Laurent E. Burnout-depression overlap: a review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;36:28-41. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.004

- Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T. A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. [Review]. 2016;1(1):132-149.

- Lindeman B, Petrusa E, McKinley S, et al. Association of Burnout With Emotional Intelligence and Personality in Surgical Residents: Can We Predict Who Is Most at Risk? J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):e22-e30. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.11.001

- Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Association of Clinical Specialty With Symptoms of Burnout and Career Choice Regret Among US Resident Physicians. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1114-1130. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.12615

- McKinley TF, Boland KA, Mahan JD. Burnout and interventions in pediatric residency: A literature review. Burn Res. 2017;6:9-17. doi:10.1016/j.burn.2017.02.003

- Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(9):1681-1694. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.10.023

- Raj KS. Well-being in residency: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(5):674-684. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-15-00764.1

- Reuben DB. Depressive symptoms in medical house officers. Effects of level of training and work rotation. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145(2):286-288. doi:10.1001/archinte.1985.00360020114019

- Sen S, Kranzler HR, Krystal JH, et al. A prospective cohort study investigating factors associated with depression during medical internship. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):557-565. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.41

- Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2373-2383. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.15845

- Campbell J, Prochazka AV, Yamashita T, Gopal R. Predictors of persistent burnout in internal medicine residents: a prospective cohort study. Acad Med. 2010;85(10):1630-1634. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181f0c4e7

- Fahrenkopf AM, Sectish TC, Barger LK, et al. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7642):488-491. doi:10.1136/bmj.39469.763218.BE

- Scheier MF, Carver CS. Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: theoretical overview and empirical update. Cognit Ther Res. 1992;16(2):201-228. doi:10.1007/BF01173489

- Dodge R, Daly AP, Huyton J, Sanders LD. The challenge of defining wellbeing. Int J Wellbeing. 2012;2(3):222-235. doi:10.5502/ijw.v2i3.4

- Salovey P, Mayer JD. Emotional intelligence. Imagination, cognition and personality. 1990;9(3):185-211. doi:10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG

- Nedrow A, Steckler NA, Hardman J. Physician resilience and burnout: can you make the switch? Fam Pract Manag. 2013;20(1):25-30.

- Lebares CC, Braun HJ, Guvva EV, Epel ES, Hecht FM. Burnout and gender in surgical training: A call to re-evaluate coping and dysfunction. Am J Surg. 2018;216(4):800-804. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.07.058

- Williams D, Tricomi G, Gupta J, Janise A. Efficacy of burnout interventions in the medical education pipeline. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(1):47-54. doi:10.1007/s40596-014-0197-5

- Lebensohn P, Kligler B, Brooks AJ, et al. Integrative medicine in residency: feasibility and effectiveness of an online program. Fam Med. 2017;49(7):514-521.

- Lebensohn P, Kligler B, Dodds S, et al. Integrative medicine in residency education: developing competency through online curriculum training. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(1):76-82. doi:10.4300/JGME-04-01-30

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Public. https://apps.acgme.org/ads/Public. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- Maslach C. Maslach Burnout Inventory. From: https://www.mindgarden.com/117-maslach-burnout-inventory-mbi. Accessed August 27, 2020.

- Maslach CJ. SE, Leiter, MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory. 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

- Cohen S W, G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, ed. The social psychology of health: Claremont symposium on applied social psychology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988.

- Lee EH. Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nurs. 2012;6(4):121-127.

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385-401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71-75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Pavot W, Diener E. Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychol Assess. 1993;5(2):164-172. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.164

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063-1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

- Davis MH. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. Catal Sel Doc Psychol. 1980.

- Davis MH. Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;44(1):113-126. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113

- Salovey P, Mayer JD, Goldman SL, Turvey C, Palfai TP. Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. In: Emotion, disclosure, & health. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1995:125-154. doi:10.1037/10182-006

- Mccullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82(1):112-127. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112

- Walach H, Buchheld N, Buttenmüller V, Kleinknecht N, Schmidt S. Measuring mindfulness—the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI). Pers Individ Dif. 2006;40(8):1543-1555. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.025

- Galwey N. The Use of Mixed Models for the Analysis of Unbalanced Experimental Designs. Introduction to Mixed Modelling. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2014:350-378. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470035986.ch8

- Hoonpongsimanont W, Murphy M, Kim CH, Nasir D, Compton S. Emergency medicine resident well-being: stress and satisfaction. Occup Med (Lond). 2014;64(1):45-48. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqt139

- Gardner RL, Cooper E, Haskell J, et al. Physician stress and burnout: the impact of health information technology. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(2):106-114. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocy145

There are no comments for this article.