Background and Objectives: Managing early pregnancy loss (EPL) with expectant, medication, and manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) management in primary care is safe, effective, and acceptable, yet, few family physicians provide all three care options. We implemented the Miscarriage Care Initiative (MCI) to help primary care organizations serving underserved communities and family medicine residencies integrate comprehensive EPL treatment options into practice. This study evaluates the effect of the MCI on provision of EPL care and family physicians’ professional growth.

Methods: This mixed-methods, cross-sectional study included family physician clinical champions from 13 sites who completed the MCI in 2013-2016. Participants were invited to complete surveys and phone interviews to assess their perceptions, experiences, and changes in clinical practice. We used descriptive statistics to summarize survey data; transcripts were coded and examined through thematic analysis.

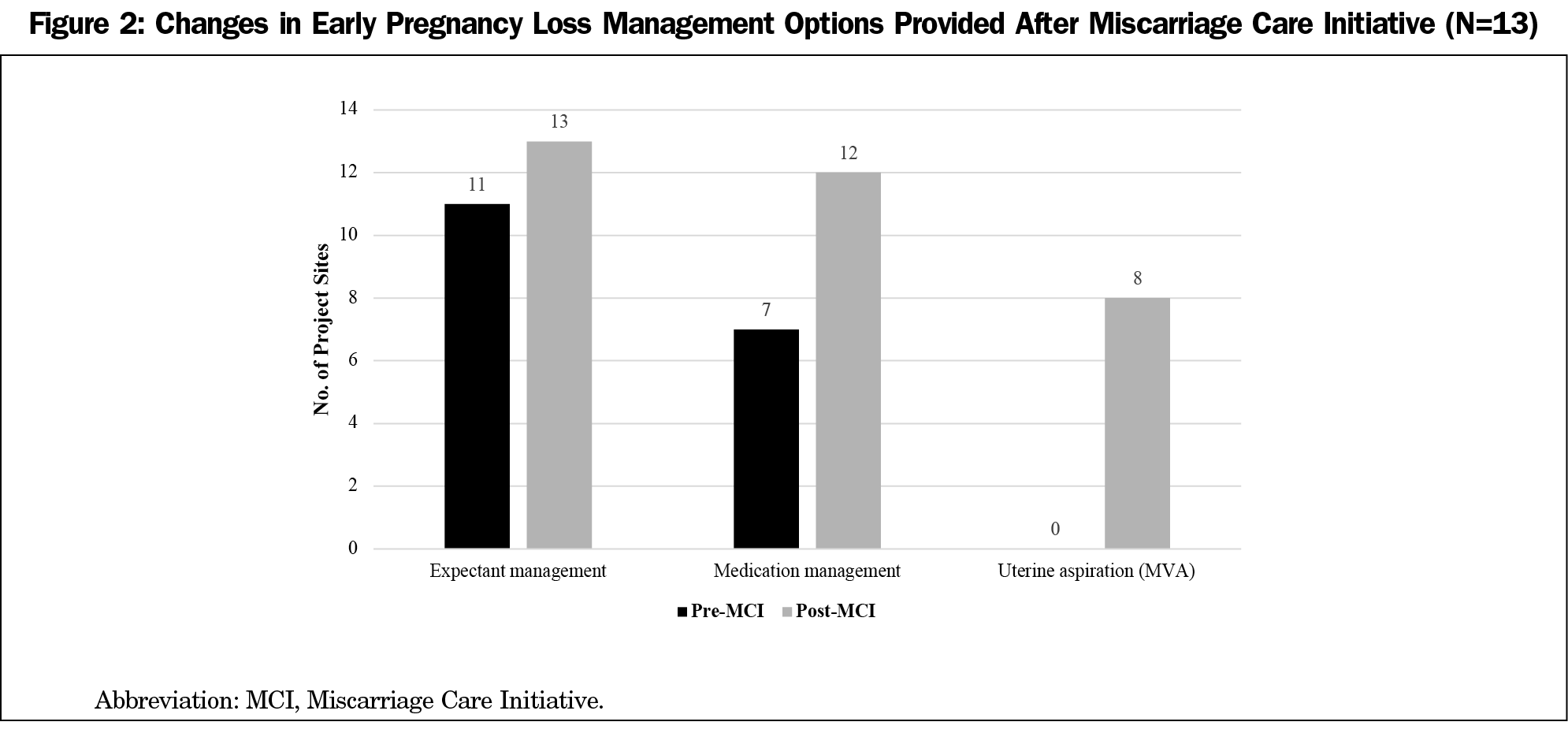

Results: All respondents completed surveys, and 11 (84.6%) completed interviews. After the MCI, nearly all sites (92.3%) offered expectant and medication management options; eight (61.5%) provided MVA for EPL. All residencies integrated comprehensive EPL management into their didactic curricula. Common challenges to integrating care included administrative resistance around EPL management similarities to abortion, and time to navigate logistics. The MCI supported family physicians’ leadership development and may contribute to increased continuity of care.

Conclusions: The MCI successfully expanded the availability of EPL management options and residency training in primary care. Future research should explore the program’s sustainability on EPL care provision and training, and strategies to scale up such a model.

Nearly one in five pregnancies end in early pregnancy loss (EPL), also known as miscarriage, and usually in the first trimester.1 For pregnant people and their families, EPL can be a traumatic experience. This may be further complicated when patients are referred to emergency rooms and unfamiliar specialists for care. While EPL has been managed with dilation and curettage in the operating room, treating EPL in office-based primary care settings is safe, effective, less costly, and acceptable.2 Treatment options include expectant management (“watch and wait”), medication management with misoprostol, and uterine aspiration with manual vacuum aspiration (MVA).3,4 Estimated rates of success to pass an EPL differ slightly by treatment and miscarriage subcategory. With expectant management, by day 14, success rates range from 52%-84%.5 For medication management with one misoprostol dose, success rates range from 81%-93%.6 With MVA, success rates are 98%-100%; it is equally effective as dilation and curettage and has fewer risks of bleeding complications.7

Patients prefer receiving EPL treatment in primary care settings due to privacy, efficiency, and comfort with one’s own clinician.7 Expanding EPL management in these settings may enhance care by offering continuity, thorough information and communication about their EPL, emotional support, and patient-centered counseling for informed decision-making with the patient’s usual clinician.8-11 Outcomes improve when patients actively participate in the decision-making process about how to manage their EPL.12

Family physicians represent over one-third of primary care clinicians in the United States and are most likely to practice in underserved urban and rural communities where access to specialist care, such as obstetrics and gynecology (Ob/Gyn), is limited.13-15 Their scope of practice includes outpatient procedures and maternal and reproductive health care, including prenatal care, contraception, abortion, and identifying and managing EPL.16,17 Despite this, family physicians provide limited EPL care in practice; most offer only expectant management.18,19

Family medicine residents are not routinely taught medication management and uterine aspiration.20 Some residency programs are working to increase EPL training, often supported by The Center for Reproductive Health Education in Family Medicine (RHEDI). Their model includes training in full-scope EPL management, contraception, patient-centered counseling, and abortion care, though residents may opt out from performing abortions.21 Additionally, 10 family medicine programs in Washington implemented the Residency Training Initiative in Miscarriage Management (RTI-MM) to address identified gaps in EPL care training and MVA.22 Beyond training, administrative resistance and managing clinic flow logistics may limit clinicians’ abilities to integrate comprehensive EPL management into primary care.23

The Reproductive Health Access Project (RHAP) trains, supports, and mobilizes family physicians and other primary care clinicians to integrate abortion, contraception, and EPL care into their practices and to advocate for improved access in their communities. RHAP implemented the Miscarriage Care Initiative (MCI) in 2013 to assist family physicians in expanding access to full-scope EPL management options in primary care settings and family medicine residency programs. This study evaluates the MCI’s effects on primary care sites’ provision of comprehensive EPL care and residency training, and on family physicians’ professional growth. Additionally, we assessed participants’ satisfaction with MCI components, perceptions of challenges to integrating EPL care into practice, and potential benefits to patients.

Program Description

The MCI provided intensive support to family physicians and their primary care organizations to help integrate comprehensive EPL care into practice. It sought to (1) increase the availability of expectant, medication, and MVA management of EPL to improve patients’ access to care within their medical homes; (2) increase the availability of training for family medicine residents in all three treatment options; and (3) support family physicians’ professional growth. The MCI was informed by the RTI-MM, Ipas, and Provide, whose programs worked with clinical champions and provided site-wide technical assistance to change practice.22,24,25

RHAP recruited potential participants through outreach with family physician colleagues and networks across the United States and posting a call for applicants on their website. From 45 applications received from 2013-2016, RHAP prioritized selecting annual cohorts of approximately five organizations with high prenatal patient volume and that predominantly care for medically underserved communities, as well as family medicine residencies and federally qualified health centers. Sites were ineligible if they provided abortion care.

Each organization selected one attending family physician clinical champion to work directly with RHAP to spearhead MCI activities. As part of the MCI, clinical champions were tasked to develop teams of clinicians, residents, administrators, and/or nurses to plan and execute implementation processes, train staff, and participate in a learning community with other clinical champions in their cohort. Agency leaders approved and signed their organization’s application to strengthen accountability to MCI activities.

Clinical champions were required to be competent to provide patient-centered pregnancy options counseling and counseling for EPL. From 2015 onward, due to the MVA training partner ending training opportunities, MCI sites were required to have their clinical champion or a clinical team member experienced in providing MVA. RHAP’s medical director participated in applicant interviews to determine whether they possessed sufficient experience.

At the start of each cohort, RHAP conducted a needs assessment with each site and developed an implementation work plan. All sites required assistance navigating administrative and logistical challenges to change practice, like developing protocols and negotiating changes with organizational leadership. Five clinical champions required MVA training and six required ultrasonography refresher training, whereas others (or clinician colleagues) were sufficiently trained through residency and prior work experiences. All had strong patient-centered counseling skills and were able to prescribe misoprostol for medication management.

Clinical champions and their respective organizations received a range of technical assistance and funding support. This included policies and procedures documents; electronic health record templates; patient education fact sheets on each EPL treatment option; sustainability planning guidance; residency curricula materials; training guides on all options; patient-centered EPL counseling; mentorship on processes of introducing practice change; group calls to share challenges and successes; individual check-ins; ultrasound machines; start-up misoprostol supplies; MVA supplies; arrangements for ultrasonography refresher training; arrangements for MVA training; and financial assistance to attend conferences.26 Additionally, RHAP provided guidance on how to facilitate values clarification workshops with staff. Though these workshops are commonly associated with helping health professionals clarify attitudes toward patients’ pregnancy decisions, they can also address health care provision barriers stemming from stigma and misinformation.27,28 Depending on sites’ needs, they received all or some of the aforementioned support. Due to funding limitations, only clinical champions were eligible for training opportunities and conference support. Each site’s project period ranged from 12-18 months.

Study Design and Data Collection

In 2017 we employed a sequential mixed-methods, cross-sectional study design consisting of surveys and subsequent semistructured, in-depth interviews. We purposefully sampled all family physician clinical champions who completed the MCI (n=13) to capture the experiences of individuals most closely involved in the program, receiving the most support, and representing each site. In order to receive MCI support, all clinical champions agreed to participate in at least the survey portion of the study. The 13 sites were involved for the full 12-18-month MCI project period. Though RHAP implemented the MCI with 16 clinical sites from 2013-2016, three began in late 2016 and had not yet received the full range of support by the time of data collection, thus were excluded from the study.

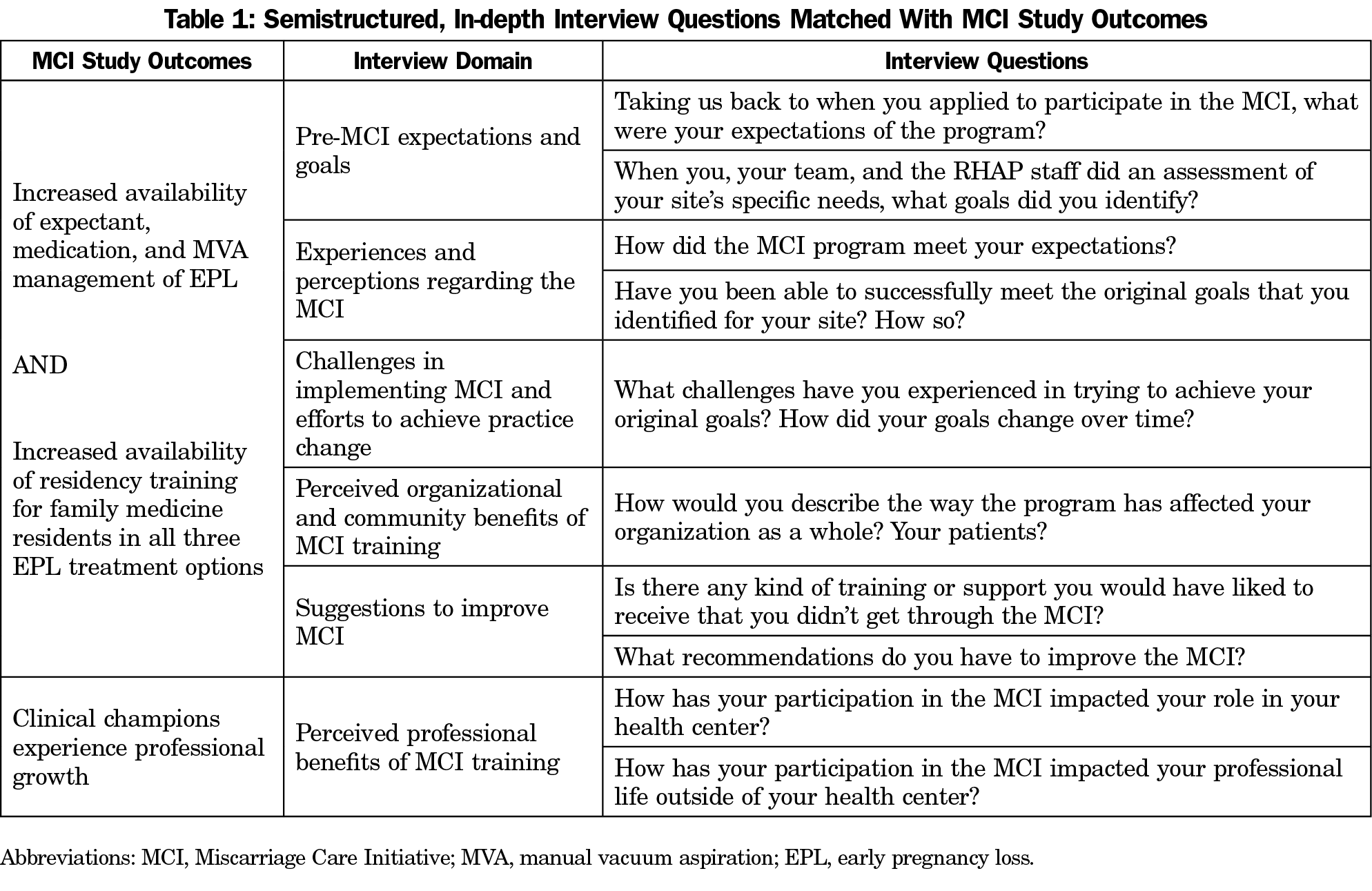

The survey included items regarding clinical champions’ perceptions and satisfaction with the aforementioned MCI components, resources, and training, EPL service provision before and after the MCI, new clinicians offering EPL management post-MCI, and changes in residency training. The semistructured interview guide explored participants’ pre-MCI goals and expectations, experiences during the MCI, organizational changes, challenges to change practice, perceived benefits of the MCI, and feedback to improve the initiative (Table 1). Staff piloted both instruments with family physicians associated with RHAP and refined them accordingly.

We emailed a web-based survey hosted on SurveyMonkey to the 13 clinical champions representing MCI sites. We sent three reminder emails to nonresponders. Once respondents completed the survey, we contacted them via email and asked them to participate in phone interviews with one of seven master of social work candidates trained in in-depth interviewing at New York University. Two declined to participate in interviews. Interviewers had no relationship with participants prior to the study. They obtained verbal consent upon starting the interview. Interviews were audio-recorded and lasted 30 minutes on average. Recordings were destroyed after verbatim transcription. As this study involved a small sample of family physicians with ongoing professional relationships with staff and others in the family medicine field, we did not collect demographic information to preserve respondent confidentiality.

Measures and Data Analysis

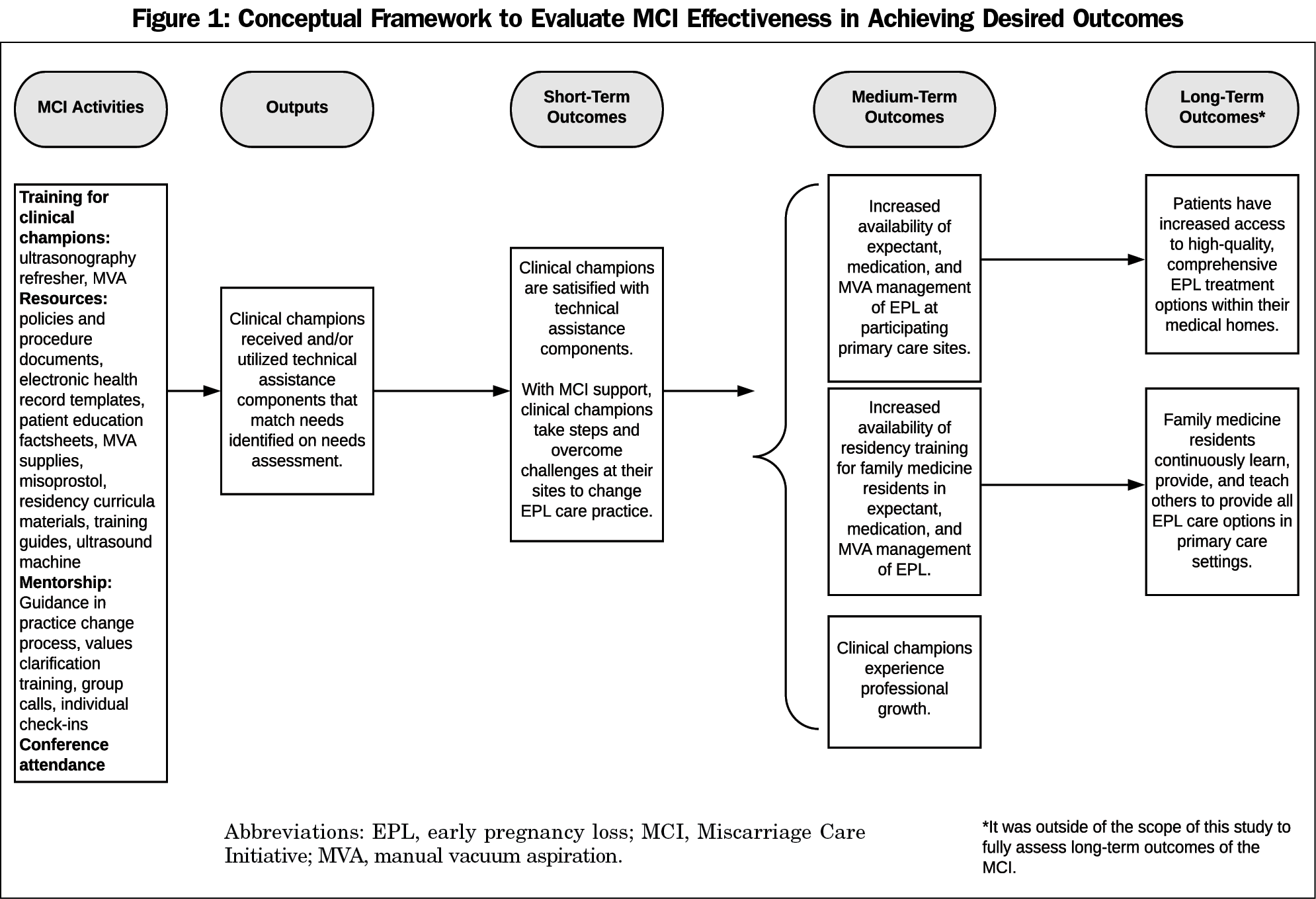

To measure the extent to which MCI outcomes were achieved, we utilized a program evaluation framework developed by the authors. We employed the logic model approach to evaluation, which maps MCI activities to short, medium, and long-term outcomes (Figure 1). This allowed us to define the intended links between program resources, strategies, immediate results, and desired accomplishments.29

Through the survey, we measured satisfaction with technical assistance components by rating various elements on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Changes in EPL care provision were measured by the number of sites that offered expectant, medication, and/or MVA management pre and post-MCI. Changes in residency didactic training curricula were measured similarly. Respondents indicated yes or no regarding whether the number of clinicians offering each type of EPL treatment option increased post-MCI.

Through interviews, we explored clinical champions’ barriers to implementing EPL care to contextualize the extent to which sites were able to utilize MCI technical assistance to change practice. We examined perceived professional benefits from participating in the MCI. Though it is outside of the scope of this study to fully assess long-term outcomes, we also report on perceptions of potential patient benefits to having EPL care offered within primary care.

We analyzed survey data using descriptive statistics in SPSS 26 (Armonk, NY). A RHAP affiliate with a doctorate in education who is trained in program evaluation and qualitative research conducted qualitative analysis. Utilizing thematic analysis, the analyst first read and annotated all transcripts to draw themes from the data.30 She organized themes into categories based on the program evaluation framework and developed a codebook accordingly. She coded each transcript independently and continuously compared, compiled, and synthesized coded themes with respect to the evaluation framework. Subsequently, she debriefed findings with the research team to interpret results. Coding and analysis were done by hand. The team practiced reflexivity throughout the analysis process by noting biases as practitioners and advocates who support expansion of contraception, EPL, and abortion in primary care.

The Institutional Review Board of the Institute for Family Health approved this study.

Quantitative Results

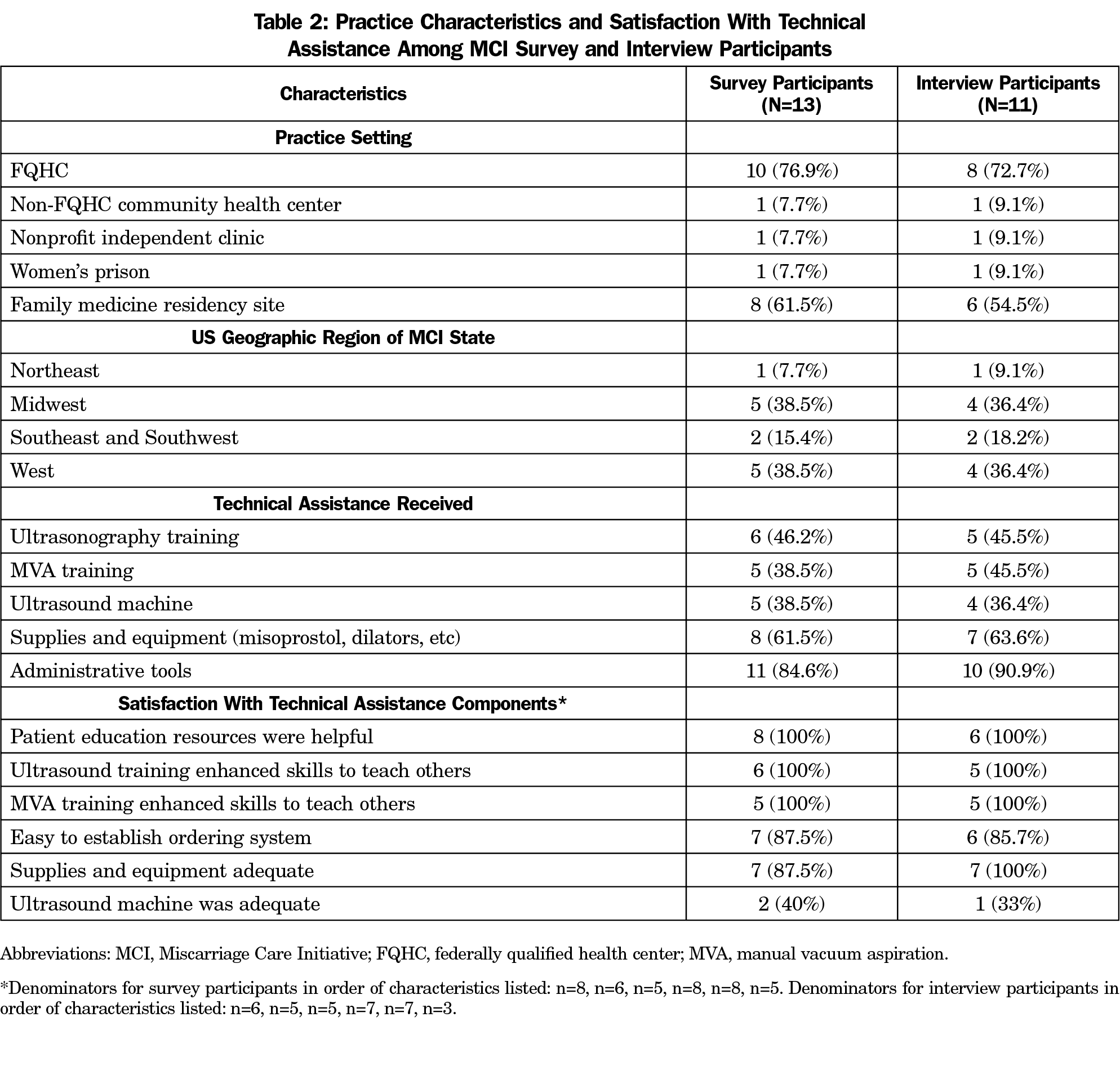

Satisfaction With MCI Technical Assistance (Table 2). All respondents from residency sites (n=8) found RHAP patient education resources and clinical tools on EPL counseling and treatment types helpful for incorporating into didactic curricula. Among those who received support with ordering and start-up supplies (n=8), most (87.5%) found it easy to establish an ordering system and the supplies adequate. Five participants received an ultrasound, but most (60.0%) disliked using it due to difficulties determining early pregnancy viability. One champion continued to use it, another convinced their site to purchase a new one, and another sent patients elsewhere to obtain sonograms.

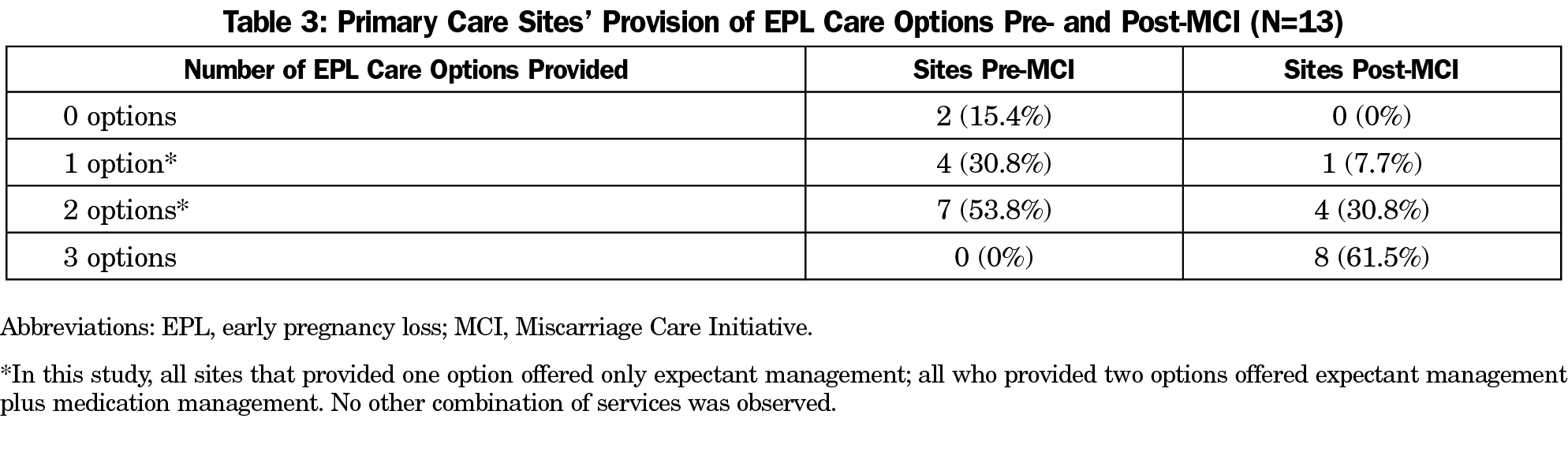

EPL Management Provision.Figure 2 illustrates changes in EPL treatment option availability across sites before and after the MCI. After the MCI, all sites (100%) offered expectant, 12 (92.3%) medication, and eight (61.5%) MVA management. Prior to the MCI, two sites did not offer any EPL care options; afterward, one integrated expectant and medication management, the other integrated all three services (Table 3). Two sites did not implement any new treatment options. After the MCI, the eight residency sites integrated all EPL treatment options into their didactic training curricula. Four provided patients with comprehensive services, and three provided medication and expectant management. At sites that already provided expectant (n=11) and medication management (n=7) prior to the MCI, four (36.3%) increased the number of clinicians able to provide expectant management, and three (42.9%) for medication.

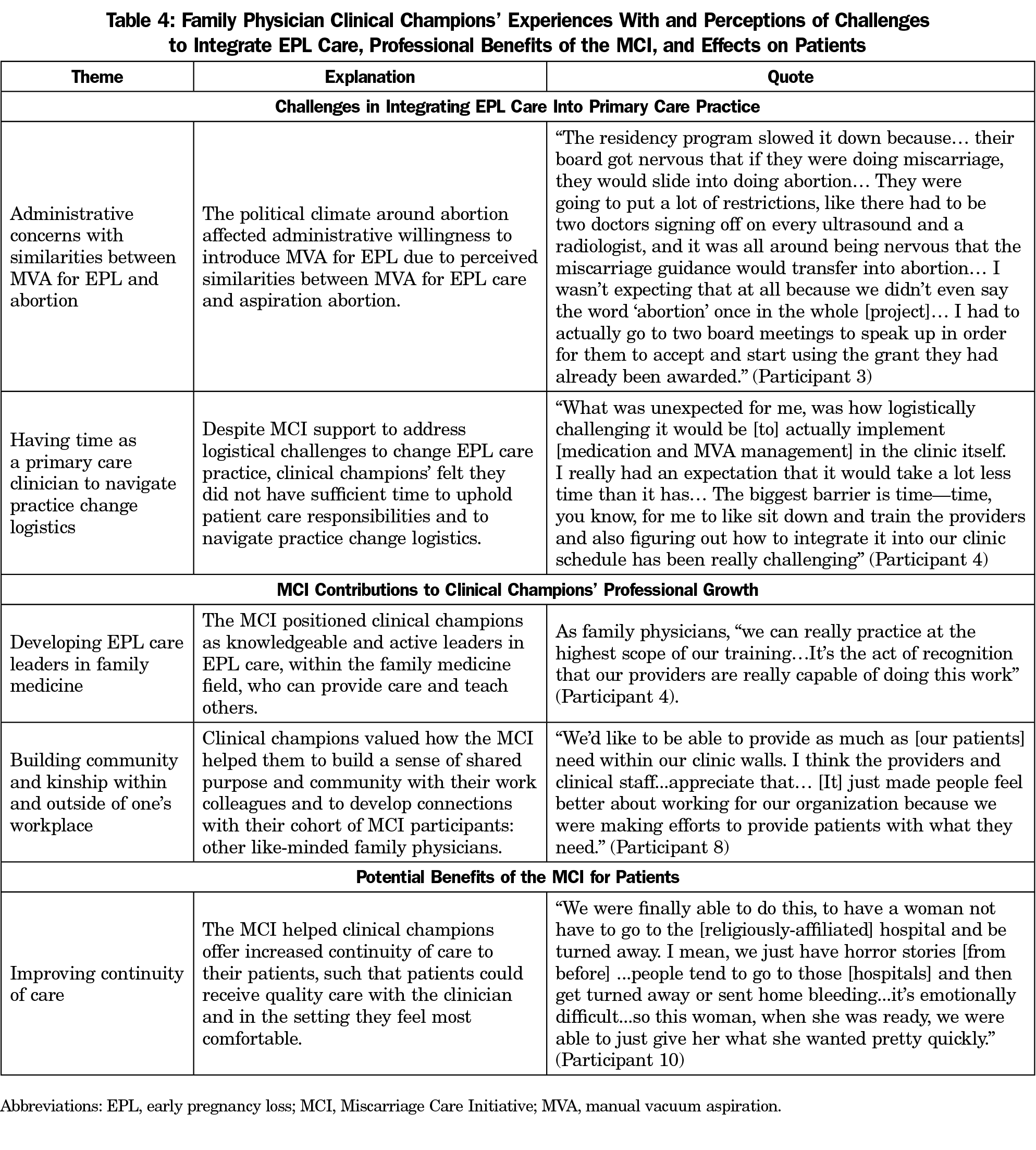

Qualitative Findings: Challenges in Integrating EPL Care (Table 4)

Though all sites offered at least expectant management post-MCI, participants expressed challenges to increase the types of options available. Obstacles centered on administrative concerns regarding similarities between MVA for EPL and abortion care and having sufficient time to navigate EPL practice change as a busy clinician.

Administrative Concerns With Similarities Between MVA for EPL and Abortion. In some communities, the political climate around abortion affected administrative willingness to introduce MVA for EPL. Some organizations delayed clinical champions’ efforts due to discomfort that providing EPL care would lead to providing abortion. Two sites were unable to overcome this administrative resistance. A respondent from one site explained,

As soon as [the new chief medical officer] saw that the organization sponsoring [the MCI] had [something] to do with abortions, he started throwing roadblocks and I couldn’t get him to sign off on the contracts. —Participant 5

Time to Navigate Practice Change Logistics. Incorporating practice and residency curricula changes for expectant, medication, and MVA management required navigating many logistics. These included,

making sure policies were in place, making sure our staff understood how the procedure worked, that all the equipment was there when we needed it (Participant 1);

and determining

‘when we would provide the procedural services and how we would have that staffed appropriately, while at the same time not affecting our productivity’ in a busy community health center. —Participant 8

This was particularly challenging as family physicians see many patients with unique needs daily. The MCI did not cover administrative time for clinical champions to problem-solve these challenges, which presented as “the biggest barrier” for some (Participant 4).

Qualitative Findings: Clinical Champions’ Professional Growth (Table 4)

Despite challenges, respondents overall felt the MCI expanded their skills and supported their professional growth by positioning them as family medicine leaders in EPL care and connecting them to a like-minded family physician community.

Developing EPL Care Leaders in Family Medicine. One participant explained that the MCI “paved the way for me to...have that broader conversation [at work, and] to be taken seriously” (Participant 6). Another emphasized the status they now have to educate about these topics:

This little family doc in the middle of [a small town] would be able to give you a lecture on miscarriage or contraception… It’s one more thing that I can put on my CV to help people trust that I can share knowledge with them. —Participant 3

Respondents also felt the MCI changed their relationships with colleagues, as they became key contacts for questions about EPL. Many reported that in their organizational culture family physicians and Ob/Gyns traditionally played very different roles. The MCI broke down these divisions: “I think that [our Ob/Gyn colleagues] are understanding more what our capabilities are and are very respectful of it” (Participant 6). Though participants felt the MCI built leadership in relevant ways, they also expressed the need to strengthen their leadership abilities further, particularly regarding their roles as clinical champions to negotiate practice changes.

Building Internal and External Community. Respondents consistently emphasized and valued how the MCI built community within their organizations and among fellow clinical champions. They and their coworkers felt unified by shared efforts to expand services and help patients “continue their care” (Participant 1).

Additionally, the MCI created new bonds and connected respondents to a wider, energizing community of reproductive health and rights advocates. One stated:

Any time you can go [to meetings] and… network and just be kind of rejuvenated in a room full of like-minded, energetic people, it’s helpful… especially for people who don’t work in a setting where that environment is readily available. —Participant 2

Another explained that having RHAP support and meeting fellow clinical champions was “very powerful,” especially as a female physician because “in this line of work, you can feel isolated” (Participant 6).

Qualitative Findings: Improving Continuity of Care (Table 4)

Nearly all respondents felt their success in expanding patient care opportunities was the most rewarding aspect of the MCI. They emphasized the importance of patients accessing care with their family physician within their medical home, rather than going to unfamiliar settings. Enhancing continuity of care by offering comprehensive EPL management can have “a lasting impact on...patients as a whole” (Participant 8).

The MCI successfully expanded availability of expectant, medication, and MVA management options at participating primary care organizations and increased the number of family physicians offering a range of treatment options for patients. While most sites integrated at least one new service, challenges emerged around navigating administrative resistance and practice change logistics. Similar studies have demonstrated that these factors create barriers to incorporating EPL care in office-based settings.22,23,30-32 Only one site was unable to overcome barriers to expand EPL care provision beyond expectant management. Overall, respondents reflected that the MCI helped improve their institutions’ EPL practice and teaching and enabled them to enhance patients’ continuity of care.

The MCI supported all eight participating family medicine residencies to incorporate comprehensive EPL management didactic training to residents; four residency programs provided full-scope EPL care options to patients. This reached approximately 32 new residents annually. Strengthening residency training may generate a ripple effect of new family physicians confident and able to provide various EPL treatment options. This is crucial, as family physicians are not routinely trained in medication management of EPL or uterine aspiration during residency.20 When family medicine residencies incorporate this training into their curricula, graduates are more likely to provide comprehensive EPL services in practice.19,22,33

Furthermore, the MCI helped clinical champions develop leadership skills to apply within their practices, communities, and the family medicine field. During the MCI, they were often asked to converse with reluctant clinical staff, administrators, and medical directors to negotiate change. Incorporating ongoing interprofessional training may have helped, as including diverse staff as teachers and learners in shared values around patient-centered care can facilitate successful EPL practice change.34 These skills are essential. Administrative opposition toward abortion care should not prevent integrating EPL management, an important health care priority, into practice. Yet, it may be more difficult to negotiate practice change today as abortion and EPL care similarities become closer. For example, recently mifepristone pretreatment (commonly used for medication abortion) has proven to increase the efficacy of medication management of EPL compared to misoprostol alone.35 This additional similarity to abortion may make it more difficult for clinicians with resistant administrators to incorporate medication management of EPL into primary care practice.

This study has several limitations. By limiting our sample to clinical champions, we were unable to learn from family medicine residents, clinical and administrative team members, and staff who opposed or engaged in the MCI reluctantly. There may have been participation bias, as sites self-selected to apply to the MCI with the shared goal of increasing EPL care provision. Additionally, two MCI participants declined interviews and may have had different experiences compared to respondents. While no study-related incentives were given to participants, all received substantial financial and technical support through the program and continued to interact with RHAP staff. As such, participants may have felt pressured to share positive experiences and minimize negative ones. Although interviewers were unfamiliar with clinical champions and not directly associated with RHAP, as social work students their interests in health and social well-being may have influenced interviews. To preserve the confidentiality of the small sample, we were unable to investigate associations between certain MCI components or demographic characteristics and changes in EPL care provision. This study may not be generalizable to primary care sites with low prenatal patient volume or existing abortion services, or to clinical champions with less baseline training in EPL counseling.

The MCI increased the availability of EPL management options for medically underserved communities and training for family medicine residents. It helped develop family physicians into leaders and build a supportive clinician community. To date, the MCI is one of few initiatives that supports primary care sites and family medicine residencies to integrate comprehensive EPL care into practice.22 Future research on similar initiatives should explore effects on diverse practice settings with lower prenatal care volume, residents’ experiences and impacts on training, patient outcomes, and sustainability of EPL service delivery and training. Additionally, RHAP is exploring strategies to scale-up the MCI to support EPL practice change for a larger cohort of primary care organizations.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the work of Linda Prine, MD and Rosann Mariappuram, JD, MA, in helping to develop the Miscarriage Care Initiative. The authors also acknowledge the work of Alyson Erardy, Pema Guttman, Tali Insel, Yim Leung, Emily Schuback, Jessica Vega, and Miriam Weinstein, who conducted interviews for this study.

Financial Support: Funding for the implementation and study of the Miscarriage Care Initiative was provided by a grant from the Grove Foundation. The Grove Foundation did not play a role in interacting with participants, study design, collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data, writing the manuscript, nor in deciding to submit this article for publication.

Presentations: Findings from the pilot year of the Miscarriage Care Initiative were presented in poster format at the American Public Health Association Annual Meeting in Chicago, Illinois, November 4, 2015, by Lisa Maldonado, Linda Prine, and GG de Fiebre, titled “Expanding community-based management of early pregnancy loss.”

Conflict Disclosure: Vicki Breitbart is a member of the Reproductive Health Access Project’s Board of Directors.

References

- Rossen LM, Ahrens KA, Branum AM. Trends in risk of pregnancy loss among US women, 1990-2011. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2018;32(1):19-29. doi:10.1111/ppe.12417

- Harris LH, Dalton VK, Johnson TR. Surgical management of early pregnancy failure: history, politics, and safe, cost-effective care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(5):445.e1-445.e5. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2007.01.013

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 200: early pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(5):e197-e207. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002899

- Prine LW, MacNaughton H. Office management of early pregnancy loss. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(1):75-82.

- Luise C, Jermy K, May C, Costello G, Collins WP, Bourne TH. Outcome of expectant management of spontaneous first trimester miscarriage: observational study. BMJ. 2002;324(7342):873-875. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7342.873

- Zhang J, Gilles JM, Barnhart K, Creinin MD, Westhoff C, Frederick MM; National Institute of Child Health Human Development (NICHD) Management of Early Pregnancy Failure Trial. A comparison of medical management with misoprostol and surgical management for early pregnancy failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(8):761-769. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa044064

- Dalton VK, Harris L, Weisman CS, Guire K, Castleman L, Lebovic D. Patient preferences, satisfaction, and resource use in office evacuation of early pregnancy failure. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(1):103-110. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000223206.64144.68

- Baird S, Gagnon MD, deFiebre G, Briglia E, Crowder R, Prine L. Women’s experiences with early pregnancy loss in the emergency room: A qualitative study. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2018;16:113-117. doi:10.1016/j.srhc.2018.03.001

- Geller PA, Psaros C, Kornfield SL. Satisfaction with pregnancy loss aftercare: are women getting what they want? Arch Women Ment Health. 2010;13(2):111-124. doi:10.1007/s00737-010-0147-5

- Meaney S, Corcoran P, Spillane N, O’Donoghue K. Experience of miscarriage: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(3):e011382. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011382

- Wallace RR, Goodman S, Freedman LR, Dalton VK, Harris LH. Counseling women with early pregnancy failure: utilizing evidence, preserving preference. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81(3):454-461. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.10.031

- Wieringa-De Waard M, Hartman EE, Ankum WM, Reitsma JB, Bindels PJ, Bonsel GJ. Expectant management versus surgical evacuation in first trimester miscarriage: health-related quality of life in randomized and non-randomized patients. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(6):1638-1642. doi:10.1093/humrep/17.6.1638

- Grumbach K, Hart LG, Mertz E, Coffman J, Palazzo L. Who is caring for the underserved? A comparison of primary care physicians and nonphysician clinicians in California and Washington. Ann Fam Med. 2003;1(2):97-104. doi:10.1370/afm.49

- Green LA, Fryer GE, Ruddy GR, et al. The family physician workforce: the special case of rural populations. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(1):147.

- Petterson S, McNellis R, Klink K, Meyers D, Bazemore A. The state of primary care in the United States: a chartbook of facts and statistics. Robert Graham Center; 2018.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Recommended curriculum guidelines for family medicine residents: women’s health and gynecological care. AAFP reprint no.282. Am Fam Physician. 2016.

- Nothnagle M, Sicilia JM, Forman S, et al; STFM Group on Hospital Medicine and Procedural Training. Required procedural training in family medicine residency: a consensus statement. Fam Med. 2008;40(4):248-252.

- Wallace R, Dehlendorf C, Vittinghoff E, Gold KJ, Dalton VK. Early pregnancy failure management among family physicians. Fam Med. 2013;45(3):173-179.

- de Fiebre G, Maldonado L, Prine L. Managing early pregnancy loss in primary care: findings from mixed-method research with family physicians trained in uterine aspiration. Presentation at the 2014 American Public Health Association Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA.

- Nothnagle M, Prine L, Goodman S. Benefits of comprehensive reproductive health education in family medicine residency. Fam Med. 2008;40(3):204-207.

- Summit AK, Gold M. The effects of abortion training on family medicine residents’ clinical experience. Fam Med. 2017;49(1):22-27.

- Darney BG, Weaver MR, Stevens N, Kimball J, Prager SW. The family medicine residency training initiative in miscarriage management: impact on practice in Washington State. Fam Med. 2013;45(2):102-108.

- Dennis A, Fuentes L, Douglas-Durham E, Grossman D. Barriers to and facilitators of moving miscarriage care out of the operating room. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2015;47(3):141-149. doi:10.1363/47e4315

- Ipas. Ipas Start-up Kit for integrating manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) for early pregnancy loss into women’s reproductive health-care services. Chapel Hill, NC: Ipas; 2009. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/HigherLogic/System/DownloadDocumentFile.ashx?DocumentFileKey=e68aeff5-d8c2-4088-8227-b23c1672685c&forceDialog=0. Accessed May 27, 2020.

- Provide. Technical Assistance. https://providecare.org/technical-assistance/. Accessed May 27, 2020.

- Reproductive Health Access Project. Miscarriage Resources. https://www.reproductiveaccess.org/resources/?rsearch=&rtopic%5B%5D=55. Accessed 19 May 2020.

- Turner KL, Pearson E, George A, Andersen KL. Values clarification workshops to improve abortion knowledge, attitudes and intentions: a pre-post assessment in 12 countries. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):40. doi:10.1186/s12978-018-0480-0

- Steinauer J. Train the trainer: how to facilitate a values clarification exercise. Ryan Training Program Webinar. San Francisco: University of California, San Francisco; 2010. https://www.innovating-education.org/cms/assets/uploads/2013/03/3.1.1B-Train-the-Trainer-Presentation.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2020.

- Frechtling JA. Logic modeling methods in program evaluation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2007.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Darney BG, Weaver MR, VanDerhei D, Stevens NG, Prager SW. “One of those areas that people avoid” a qualitative study of implementation in miscarriage management. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):123. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-13-123

- Srinivasulu S, Maldonado L, Prine L, Rubin SE. Intention to provide abortion upon completing family medicine residency and subsequent abortion provision: a 5-year follow-up survey. Contraception. 2019;100(3):188-192. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2019.05.011

- Dalton VK, Harris LH, Bell JD, et al. Treatment of early pregnancy failure: does induced abortion training affect later practices? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(6):493.e1-493.e6. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2011.01.052

- Darney BG, VanDerhei D, Weaver MR, Stevens NG, Prager SW. “We have to what?”: lessons learned about engaging support staff in an interprofessional intervention to implement MVA for management of spontaneous abortion. Contraception. 2013;88(2):221-225. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2013.06.007

- Schreiber CA, Creinin MD, Atrio J, Sonalkar S, Ratcliffe SJ, Barnhart KT. Mifepristone pretreatment for the medical management of early pregnancy loss. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2161-2170. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1715726

There are no comments for this article.