Background and Objectives: In its landmark report, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, the Institute of Medicine concluded that unconscious or implicit negative racial attitudes and stereotypes contribute to poorer health outcomes for patients of color. We describe and report on the outcome of teaching a workshop on the tool of racial affinity caucusing to address these issues.

Methods: Applying the framework described by Crossroads Antiracism Organizing and Training, we developed a 90-minute workshop teaching racial affinity caucusing to family medicine educators interested in racial health disparities. The workshop included didactic and experiential components as well as a panel discussion. We administered pre- and posttests.

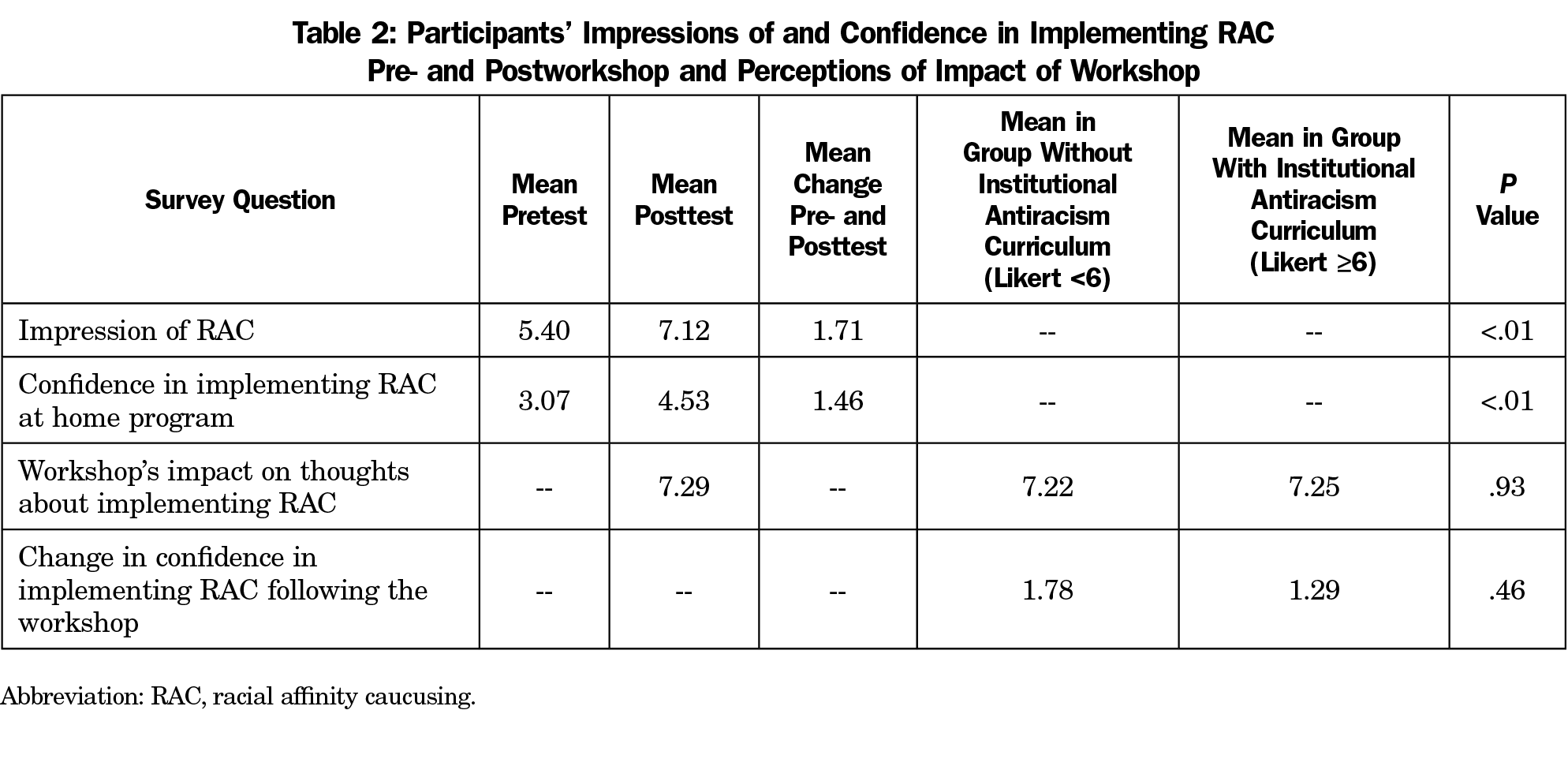

Results: Participants’ (n=53) impression of and confidence in implementing racial affinity caucusing significantly increased following the workshop from a mean pretest score of 5.40 to a mean posttest score of 7.12 (P<.01) on a scale of 1 to 9. Ninety-two percent of participants indicated that the workshop made them more likely to think about implementing this tool at their home institutions (P<.01).

Conclusions: This study demonstrated the first exploration in medical education of racial affinity caucusing and illustrated that it can be easily implemented in residency programs as an effort to address racial health inequities. Though the participating educators were mostly unfamiliar with it, the workshop was an effective introduction to this tool and by the end, educators reported increased comfort and enthusiasm for racial affinity caucusing, regardless of their preexisting levels of knowledge of or comfort with the tool. In addition, the overwhelming majority of the participants felt they could implement it at their respective institutions.

In its landmark report, the Institute of Medicine concluded that implicit negative racial attitudes and stereotypes contribute to poorer health outcomes for patients of color.1 Reducing racial health inequities requires introspection of implicit biases, privilege, and behaviors that perpetuate systemic racism. Despite interest, studies describing effective forms of teaching about racism, much less undoing racism, are severely lacking.2

Racial affinity caucusing (RAC) is a tool to explore racism and privilege. RAC intentionally separates white people from people of color (POC), allowing the former group to explore white identity and privilege and the latter to explore collective healing from negative racialized experiences and internalized racism, the process by which POC adopt racially prejudiced attitudes and behaviors themselves. While there are studies on and guides for RAC implementation in social service organizations and elementary through graduate schools, none exist in medical education.3-13 Family medicine residency programs are beginning to incorporate this method into their antiracism curricula.14 This study is not only the first to examine acceptability of RAC in medical education but also the first to evaluate methods of teaching RAC. We hypothesized that an experience of RAC, would foster educators’ confidence in their ability to introduce RAC to their programs.

We formed a working group in 2017 to learn from each other and practice RAC at our local family medicine residencies. Applying the framework described by Crossroads Antiracism Organizing and Training,15 we developed a 90-minute workshop for the Society for Teachers of Family Medicine’s 2018 Annual Spring Conference. The study population was a convenience sample of workshop participants.

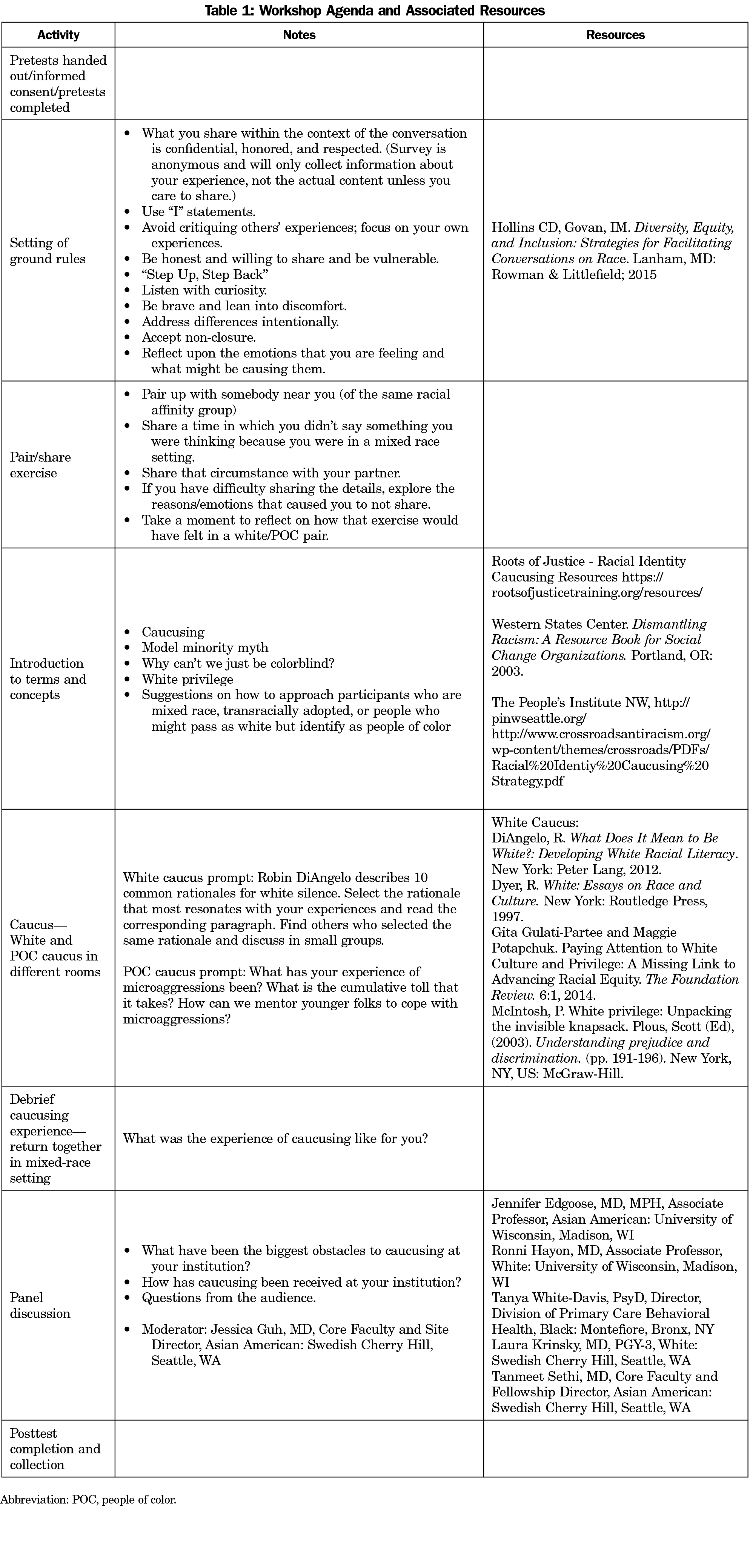

Table 1 describes the workshop which included a didactic portion, an experiential component in which participants engaged in RAC based on self-identified racial identity, a debrief and a panel of RAC practitioners who shared their experiences.

Participants completed a five-question Likert scale pretest at the outset of the workshop and a four-question Likert scale posttest. Pre- and posttests were paired by participants with a confidential identifier. We excluded incomplete pre- and/or posttests from analysis. Exclusion criteria included those who did not attend the workshop or did not consent to participate in the study.

The primary objective of the study was assessment of participants’ impressions of and experience with RAC before and after the workshop. Secondary outcomes included participants’ likelihood of implementing RAC at their home institutions and the impact of participants’ perceptions of their home institutions’ antiracism curriculum on the likelihood of implementation of RAC. We used nonparametric analysis of change in Likert scale responses between the pretest and posttest (Wilcoxon sign-rank tests); significance was set at P<.05. The institutional review board at Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine approved this project.

Fifty-three participants submitted pre and posttest surveys. Two participants were excluded from analysis due to incomplete survey responses. Prior to the intervention, only three participants reported prior experience with RAC on the pretest survey (Likert scale >4, indicating minimal prior experience). There was marked variety in participants’ perception of their home institution’s antiracism curriculum, ranging from 1-9 on a Likert scale, with the mean of 5 corresponding to “racism is recognized but there is no institutional work.”

Participants’ impression of RAC significantly increased following the workshop, from an initial neutral impression to a positive impression (Table 2; P<.01). Participants’ confidence in implementing RAC at their home institution also significantly increased (Table 2; P<.01). Ninety-two percent of participants indicated that the workshop made them more likely to implement RAC.

The increase in confidence in implementing RAC did not significantly differ between participants whose home program had already engaged in institutional antiracism work compared to those who had not yet engaged in this work (Table 2; P=.46). Similarly, the workshop’s impact on participants’ thoughts about implementing RAC did not significantly differ between these two groups (Table 2; P=.93). In other words, after the workshop, all participants felt more confident in implementing RAC, regardless of their baseline experience with antiracism curriculum.

Medical educators need effective ways to teach and remedy the impact of racism on health outcomes and health care trainees. This study demonstrated the first exploration of RAC in medical education as an effort to address racial health inequities. Although it is a known tool in other disciplines, it is virtually unknown in medical education. Though the participating educators were mostly unfamiliar with RAC, the workshop was an effective introduction to this tool, likely because of RAC’s experiential nature. After the workshop, educators reported increased comfort and enthusiasm for RAC, regardless of their preexisting levels of knowledge of or comfort with the tool. In addition, the overwhelming majority of the participants felt they could implement RAC at their respective institutions. These are critical outcomes because there are few, if any, curricular resources to address the known role our own implicit biases can play in poorer outcomes for patients of color. A 2007 systematic review16 identified six evidence-based interventions to target implicit bias: understanding the psychological basis of bias, enhancing provider confidence, increasing perspective-taking and empathy, understanding the historical context of racism, regulating emotional responses, and building partnerships with patients. RAC is a powerful tool that can encompass all of these interventions.

Strengths of this study include the ease with which this new concept was introduced and the confidence instilled. It models how this tool could be taught widely and then implemented as a pivotal piece of curriculum in all residency programs to address racial health inequities. Weaknesses include the lack of follow-up which does not allow for complete assessment of the long-term impact of the intervention. Another is the use of a convenience sample of self-selected participants interested in antiracist teaching techniques that creates the possibility of a sample of participants who are biased towards reporting more effect of the intervention. The absence of a control group also limits an assessment of the effect of the intervention. If there were a control group, it would be even more imperative to have follow up to evaluate what the longer-term effect of an intervention is on the respective programs the participants come from.

Subsequent studies could include follow-up to evaluate implementation rates of the RAC curriculum at participants’ home institutions. Research into the impact of longitudinal RAC on patient-provider interactions or patient outcomes has also never been done. Another area of further research would be the impact of longitudinal RAC on biases seen in learner evaluation, interviews, and recruitment. While this study did not address the direct impact of RAC on implicit bias and understanding of privilege future studies could explore that further. Thus, while more study is needed, it is possible that implementing RAC could be a powerful tool to help address contributors to poor health outcomes for our most vulnerable populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Barry Saver, MD, for his contributions.

Presentations: This study was presented at the STFM Annual Spring Conference in Washington, DC, May 2018.

References

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2003.

- Washington JC, Rodríguez JE. Racism education is needed at all levels of training. Fam Med. 2018;50(9):711-712. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.424750

- Tauriac JT, Kim GS, Sariñana SL, Tawa J, Kahn VD. Utilizing affinity groups to enhance intergroup dialogue workshops for racially and ethnically diverse students. J Spec Group Work. 2013;38(3):241-260. doi:10.1080/01933922.2013.800176

- Blitz LV, Kohl BG Jr. Addressing racism in the organization: the role of white racial affinity groups in creating change. Adm Soc Work. 2012;36(5):479-498. doi:10.1080/03643107.2011.624261

- Hudson KD, Mountz SE. Teaching note—third space caucusing: borderland praxis in the social work classroom. J Soc Work Educ. 2016;52(3):379-384. doi:10.1080/10437797.2016.1174633

- Abdullah CM, McCormack S. Dialogue for affinity groups: optional discussions to accompany facing racism in a diverse nation. Hartford, CT: Everyday Democracy; 2008, http://www.everyday-democracy.org/resources/dialogue-affinity-groups. Accessed February 5, 2020.

- Gulati-Partee G, Potapchuk M. Paying attention to white culture and privilege: a missing link to advancing racial equity. The Foundation Review. 2014;6(1). doi:10.9707/1944-5660.1189

- Griffith DM, Mason M, Yonas M, et al. Dismantling institutional racism: theory and action. Am J Community Psychol. 2007;39(3-4):381-392. doi:10.1007/s10464-007-9117-0

- Douglas PH. Affinity groups: catalyst for inclusive organizations. Employ Relat Today. 2008;34(4):11-18. doi:10.1002/ert.20171

- Lambertz-Berndt M. Communicating identity in the workplace and affinity group spaces. Stud Media Commun. 2016;4(2):2325-8071. doi:10.11114/smc.v4i2.1952

- Michael A, Conger M. Becoming an anti-racist white ally: how a white affinity group can help. Perspective on Urban Education. 2009;6(1):56-60.

- Picower B, Kohli R. Confronting Racism in Teacher Education. New York: Routledge; 2017. doi:10.4324/9781315623566

- Parsons J, Ridley K. Identity, affinity, reality: making the case for affinity groups in elementary school. Indep Sch. 2012;71(2).

- Guh J, Harris CR, Martinez P, Chen FM, Gianutsos LP. Antiracism in residency: a multimethod intervention to increase racial diversity in a community-based residency program. Fam Med. 2019;51(1):37-40. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.987621

- Crossroads Antiracism Organizing and Training. Racial Identity Caucusing: A Strategy for Building Anti-Racist Collectives. http://www.crossroadsantiracism.org/wp-content/themes/crossroads/PDFs/Racial%20Identiy%20Caucusing%20Strategy.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2020.

- Burgess D, van Ryn M, Dovidio J, Saha S. Reducing racial bias among health care providers: lessons from social-cognitive psychology. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):882-887. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0160-1

- Hollins CD, Govan IM. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion: Strategies for Facilitating Conversations on Race. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield; 2015.

- Roots of Justice. Racial Identity Caucusing Resources https://rootsofjusticetraining.org/resources/. Accessed February 5, 2020.

- Western States Center. Dismantling Racism: A Resource Book for Social Change Organizations. Portland, OR; 2003. http://intergroupresources.com. Accessed February 5, 2020.

- DiAngelo R. What Does It Mean to Be White? Developing White Racial Literacy. New York: Peter Lang; 2012.

There are no comments for this article.