Background and Objectives: Both the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) and the American Academy of Family Physicians have developed strategic plans to increase the training of underrepresented minority in medicine (URMM) family physicians to meet the needs of an increasingly diverse patient population in the United States. This study examines data from the 2017 Council of Academic Family Medicine (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) Program Directors (PD12) Survey to assess whether recruitment strategies increase the diversity of underrepresented minority physicians in family medicine.

Methods: Data were collected from an online electronic survey administered by the CERA of family medicine program directors in 2018. The data included specific questions about the diversity of URMM residents in family medicine programs and about initiatives that were used in their recruitment. We analyzed the data using the Pearson χ2 criteria for cause and effect of two variables.

Results: Family medicine residency programs that have initiatives dedicated to increasing resident diversity have a higher percentage of URMM residents. Specifically, residency programs that have URMM recruitment strategies are 2.5 to 4 times more likely to have a diverse residency population than those programs without strategies (P<.001-.015).

Conclusions: Striving to improve diversity in family medicine residency training in accordance with the ideals of STFM will require programs to design and implement initiatives to increase recruitment of URM residents.

The Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) identified diversity as one of its core values in 2015 and presented goals for leadership development and workforce recruitment that would enable residency programs to “proactively respond to the changing health care landscape.”1 These ideals were echoed by the American Academy of Family Physicians:

The American Academy of Family Physicians is dedicated to developing a family medicine workforce as diverse as the US population.2

Census Bureau data from 2018 indicate that the US population is 60.4% non-Hispanic White, 18.3% Latinx, 13.4% Black, 5.9% Asian, and 1.5% Native American or Pacific Islander.3 A 2018 retrospective cohort study of 147,815 primary care physicians identified 72% as non-Hispanic White, while only 6.8% were Black, 5.9% were Hispanic, 0.7% were Native American, and 11.2% were Asian.4 Except for Asian Americans, these numbers are far below the actual population of color in the United States. Although the diversity of family medicine residents had improved in terms of underrepresented minorities in medicine (URMM) from 1990 to 2012, that growth did not keep pace with the increase in the population of these minority groups.5

Physicians of color care for a disproportionate share of the underserved population, including 53.5% of minority and 70.4% of non-English speaking patients.6 A Commonwealth Fund review adduced evidence that patient–provider race concordance is associated with better patient ratings of care among adult primary care patients and better patient–physician communication.7 In a study of African American and Hispanic patients given a choice, nearly one-quarter of those groups chose a physician explicitly based on the physician’s race or ethnicity.8

The purpose of this study is to examine data from the 2017 CERA Program Directors (PD12) Survey about residency diversity to assess whether initiatives to recruit residents are needed to increase the prevalence of residents from URMM groups. If special processes in recruitment do boost diversity, then residency directors should consider implementing these to meet the needs of the diverse population of the United States.

Data were collected through a survey of family medicine program directors sent by CERA administrative personnel that took place between January 10, 2018 and February 28, 2018. The survey was sent online to 558 program directors with 298 respondents (57% response rate).9 The Institutional Review Board of the American Academy of Family Physicians approved the research.10 Two questions (#66 and #67) focused on initiatives to increase URMM resident recruitment. The first question asked which programs had diversity initiatives and what those initiatives were. We further examined the data to see if there was a correlation between programs with specific recruitment strategies and those with a number of URMM residents that approach or mirror the percentage of people of color in the United States. We analyzed the data using Pearson χ2 criteria.

Of the 259 respondents to question 66, 145 (56%) stated that their programs have specific initiatives to increase residency diversity, and 114 (44%) programs indicated that there were no initiatives (Table 1).

The next question (67) asked:

Over the past 5 years, approximately what percentage of the residents in your program are from groups underrepresented in medicine?

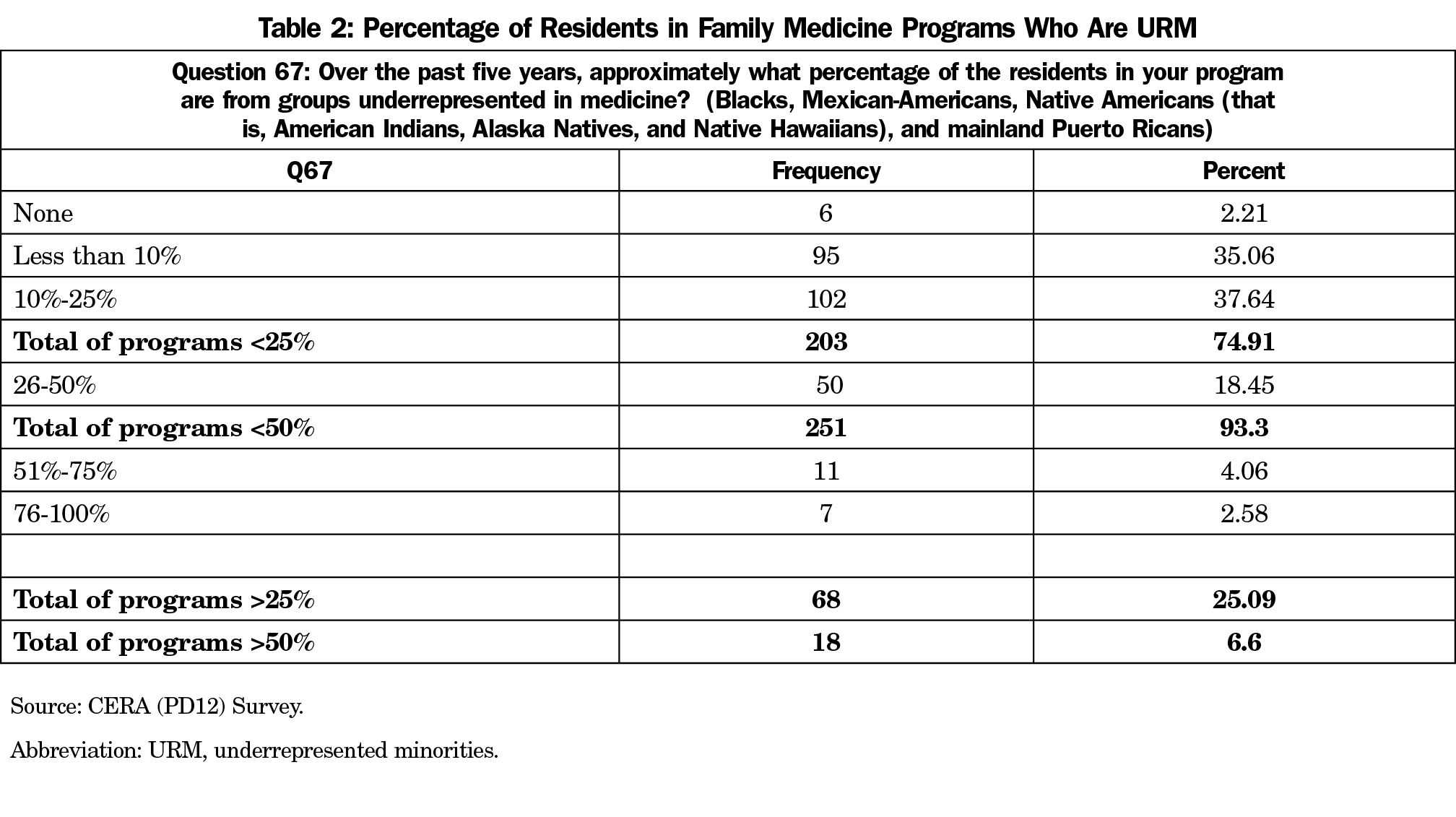

For the CERA study, URMM was defined as Black, Mexican-American, Native American and mainland Puerto Rican.11 These data were pooled into less diverse (<25% URMM), moderately diverse (26%-50% URMM) and highly diverse programs (51%-100% URMM). Diversity was based on census data showing the current United States Latinx, Black, and Native American population of 33.2% and projections for people of color to be >50% by 2045.11 Seventy five percent of residency programs were less diverse, 18.4% were moderately diverse, and 6.6% were highly diverse (Table 2).

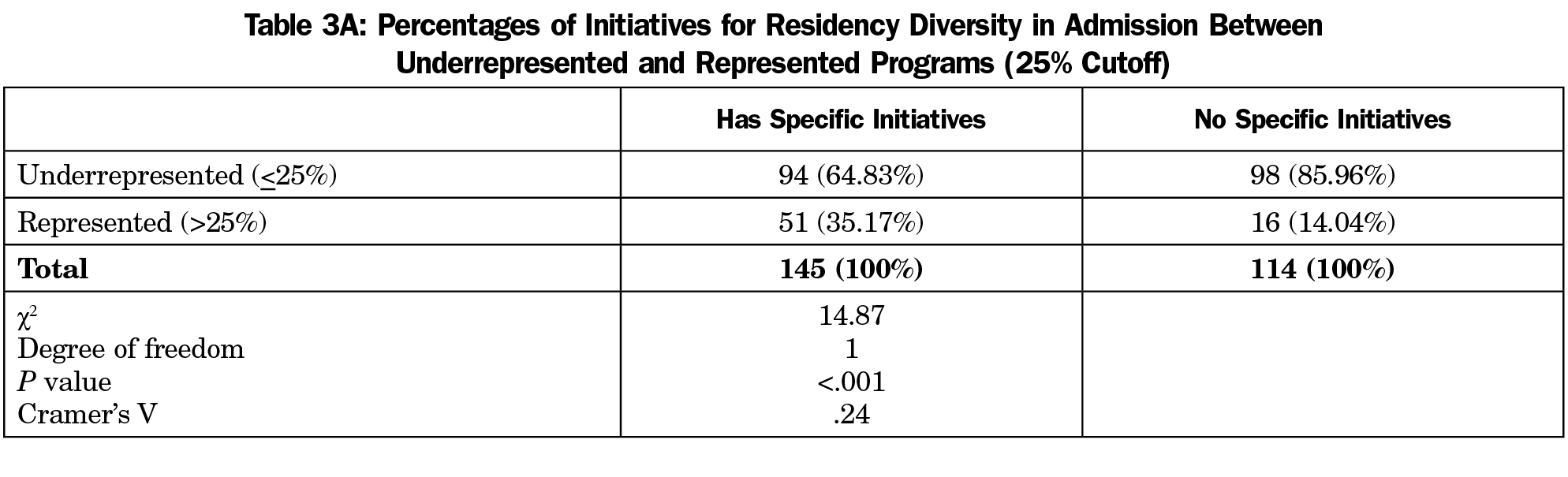

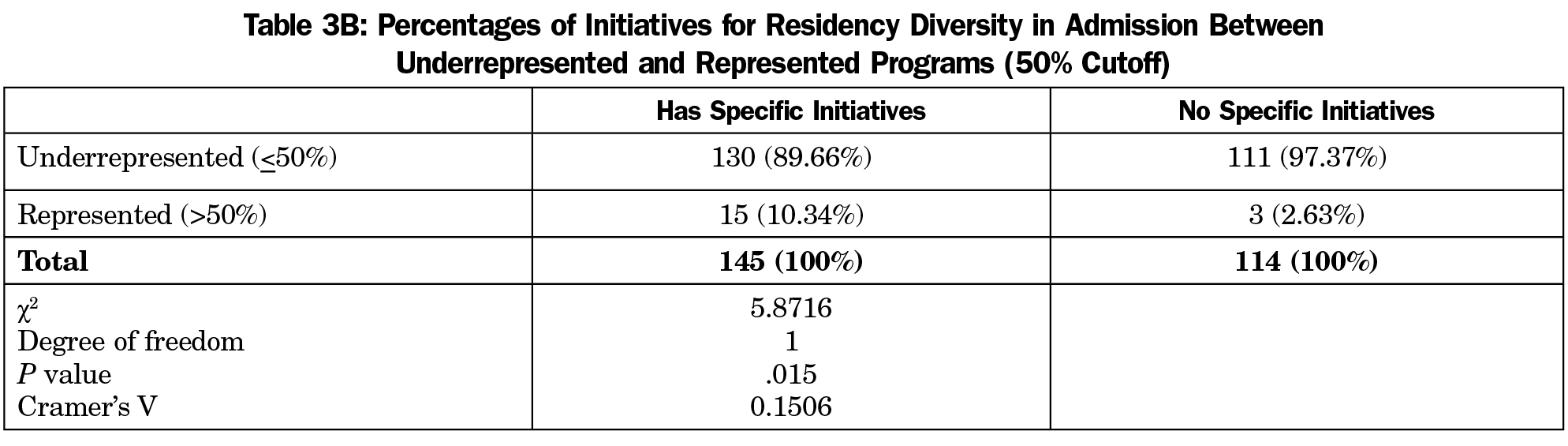

Pearson χ2 analysis showed that residency programs that had specific initiatives for recruitment were 2.5 (35%: 14%) times more likely to have at least 25% URMM, and 4.0 (10.4%: 2.6%) times more likely to have at least 50% URMM compared to programs without initiatives (χ2 =14.9, P<.001, and χ2 =5.9, P=.015, respectively; see Tables 3A and 3B).

From the evidence presented in this analysis, a slight majority of family medicine programs (56%) have initiatives in place to reach the goal of matching URMM to the current population of color in the United States. The CERA data show that programs with recruiting initiatives were 2.5 times more likely to have more than 25% URMM and 4 times more likely to have more than 50% URMM than programs without initiatives. With demographic projections of the United States becoming minority (non-Hispanic) White in 2045, there is significant work that needs to be done to recruit URMM primary care physicians.11

There are several limitations of this CERA analysis. First, question 66 asks about diversity initiatives, but does not define that specific to recruitment of URMM as defined in question 67. Also, the definition of URMM used in the study is limited to four racial/ethnic groups and does not embrace the new nomenclature from the AAMC in 2003 defining URMM as:

those racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in the medical profession relative to their numbers in the general population.12

For example, Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans comprise only 72% of the Latinx population but were the only ones counted in this study.13 In addition, the CERA data is limited in that it is a self-report by residency directors of the percentage of URMM and not the actual number of URMM over 5 years. Finally, this analysis does not address the influence of location on resident diversity due to differing regional demographics.

Currently, the United States is battling a pandemic that has placed a “disproportionate burden of illness and death among racial and ethnic minorities,” highlighting long-standing health care disparities.14 Building a health care workforce that promotes trust and with which patients identify is an important component in addressing these inequalities. Physicians of any race/ethnicity need to recognize and address implicit biases that can hinder patient-provider information.14 Further work is necessary to determine which recruitment initiatives are successful including improving the URMM pipeline to develop this workforce.

References

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. 2020-2024 Strategic Plan. https://www.stfm.org/about/governance/strategicplan/. Accessed July 16, 2020.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. The EveryONE Project: Workforce Diversity. https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/social-determinants-of-health/everyone-project/workforce.html. Accessed July 16, 2020.

- United States Census Bureau. Quick Facts. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PSTO45218-accessed. Accessed July 16, 2020.

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA. The Racial and Ethnic Composition and Distribution of Primary Care Physicians. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29(1):556-570. doi:10.1353/hpu.2018.0036

- Xierali IM, Hughes LS, Nivet MA, Bazemore AW. Family medicine residents: increasingly diverse, but lagging behind underrepresented minority population trends. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(2):80-81.

- Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, Bor DH, McCormick D. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):289-291. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12756

- Cooper LA, Powe NR. Disparities in patient experiences, health care processes and outcomes: the role of the patient-provider racial, ethnic and language concordance. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; July 1, 2004. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_fund_report_2004_jul_disparities_in_patient_experiences__health_care_processes__and_outcomes__the_role_of_patient_provide_cooper_disparities_in_patient_experiences_753_pdf.pdf. Accessed July 16, 2020.

- Somnath Saha SH, Taggart MK, Bindman AB. Do patients choose physicians of their own race? Health Aff. 2000;19(4). doi:10.1377/hlthaff.19.4.76

- CAFM Educational Research Alliance. 2017 Program Directors Survey Results. https://www.stfm.org/publicationsresearch/cera/pasttopicsanddata/2017programdirectors-pd12-survey/. Accessed July 16, 2020.

- Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW; DA. Creating a centralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257-260. doi:10.1370/afm.2228

- Frey WH. The US will become ‘minority white’ in 2045, Census projects. Brookings Institute: The Avenue. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2018/03/14/the-us-will-become-minority-white-in-2045-census-projects/. Published March 14, 2018. Accessed July 16, 2020.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Underrepresented in Medicine Definition. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/diversity-inclusion/underrepresented-in-medicine. Accessed April 23, 2020.

- Us Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=64-. Accessed April 28, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 in Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html. Updated June 25, 2020. Accessed July 16, 2020.

There are no comments for this article.