Background and Objectives: Research shows that limited time, lack of funding, difficulty identifying mentors, and lack of technical support limit resident and faculty ability to fully participate in scholarly activity. Most research to date focuses on medical student and resident attitudes toward research. This study aimed to understand the underlying attitudes of family medicine residency (FMR) leaders toward scholarship.

Methods: Two focus groups of family medicine residency leaders were conducted in March 2018. The sample (N=19) was recruited through the membership directory of the Family Physicians Inquiry Network.

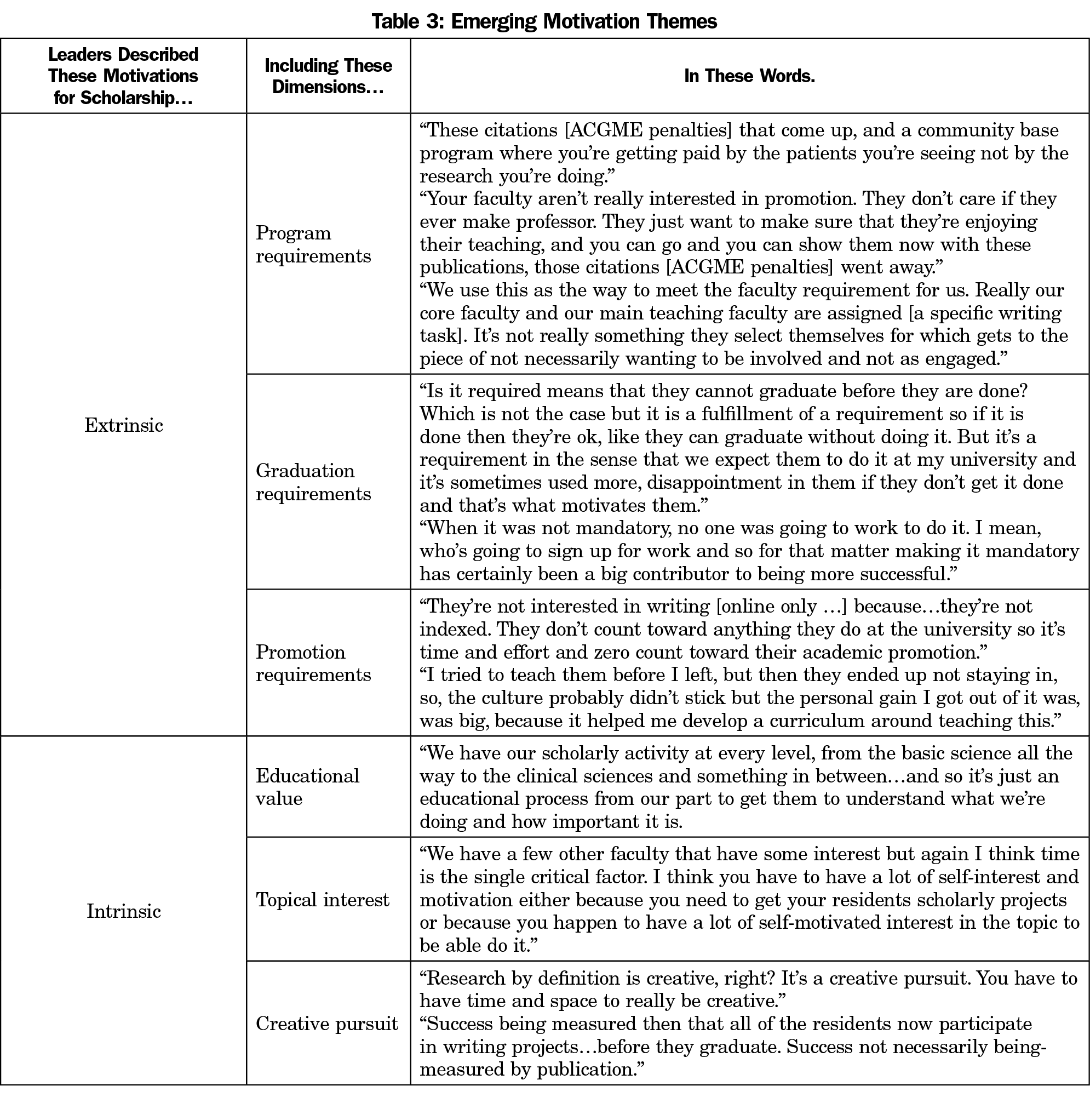

Results: Leaders shared positive attitudes toward scholarship; however, motivation to engage residents and residency faculty in scholarship diverged. Motivations for promoting scholarly activity among participants were either extrinsic (through ACGME, program graduation, or promotion requirements) or intrinsic (through personal interest and natural drive).

Conclusions: Emerging themes illustrate differences in how FMR program leaders perceive the role of scholarship in residency programs. As programs aim to increase research and scholarship, more attention must be paid to the motivating messages communicated by the program’s leadership.

In 2006, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) introduced scholarly activity requirements,1 and in 2013 it specified faculty requirements.2 These requirements created the potential for two mechanisms of culture change: policy change, which communicates new priorities and rules, and generational change, which socializes new residents who will be the faculty of tomorrow.3 Box 1 contextualizes these changes within the history of scholarship in family medicine.

The primary role of organization leaders is to create and manage culture.3 Using survey methods, researchers have assessed program director attitudes toward scholarly activity and barriers to residency scholarship.1,4-10 Within primary care specialties, survey studies reveal frustration with barriers and the overall lack of scholarly production.1,11,12 Reported barriers include limited time, little funding, difficulty identifying mentors, and insufficient technical support.13-16 Although survey research revealed program characteristics related to scholarship success,17-21 it cannot provide a rich understanding of residency leadership perspectives on scholarship. Qualitative inquiry into how leaders perceive these requirements and how they communicate about requirements can provide deeper understanding of leader perspectives.22

This study aimed to understand the underlying attitudes of family medicine residency (FMR) leaders toward scholarship.

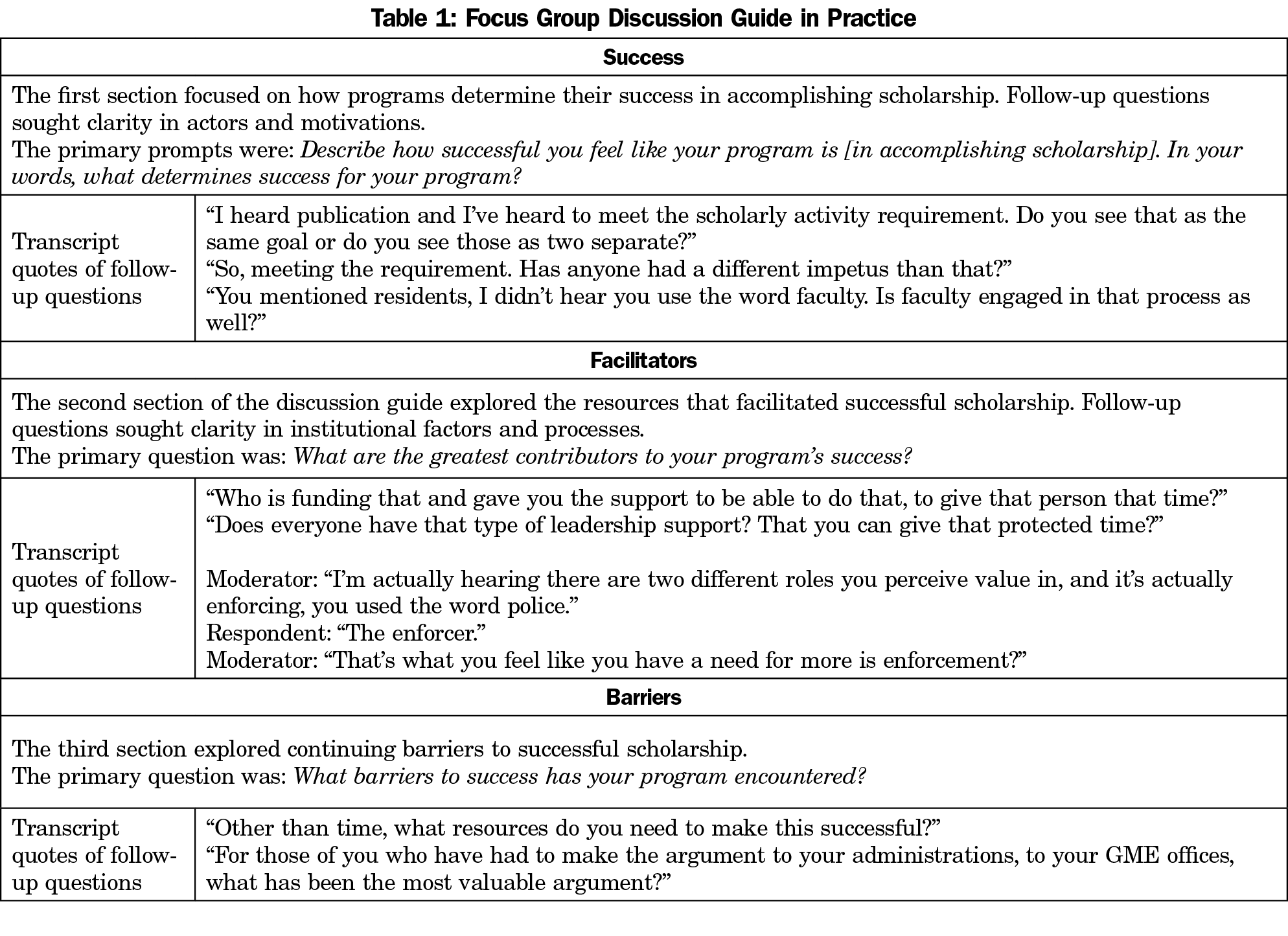

Following approval from Wilford Hall Ambulatory Surgical Center Institutional Review Board, two focus groups were conducted at the American Academy of Family Physicians 2018 Program Directors Workshop. Purposive sampling targeted residency leadership through the Family Physicians Inquiries Network (FPIN) membership directory (past and current). The fourth author moderated both groups,23 following a semistructured discussion guide. Open-ended questions within broad topics of success, facilitators, and barriers allowed for flexibility of group discussion and moderator follow-up (see Table 1 for group discussion guide). Each group occurred for 80 minutes in a hotel conference room. Audio recordings resulted in 83 pages of transcribed text.

The first author conducted a thematic analysis using the constant comparative method.24 Initial analysis identified two primary themes of extrinsic or intrinsic motivations to engage in scholarship. The first and fourth authors met to discuss emergent themes. Axial coding then identified dimensions of each motivation and highlighted key aspects of the theme.

As a validation strategy, six additional FMR leaders (none connected to FPIN member programs) were invited to review findings. Each provided a peer check, supporting content validity.26

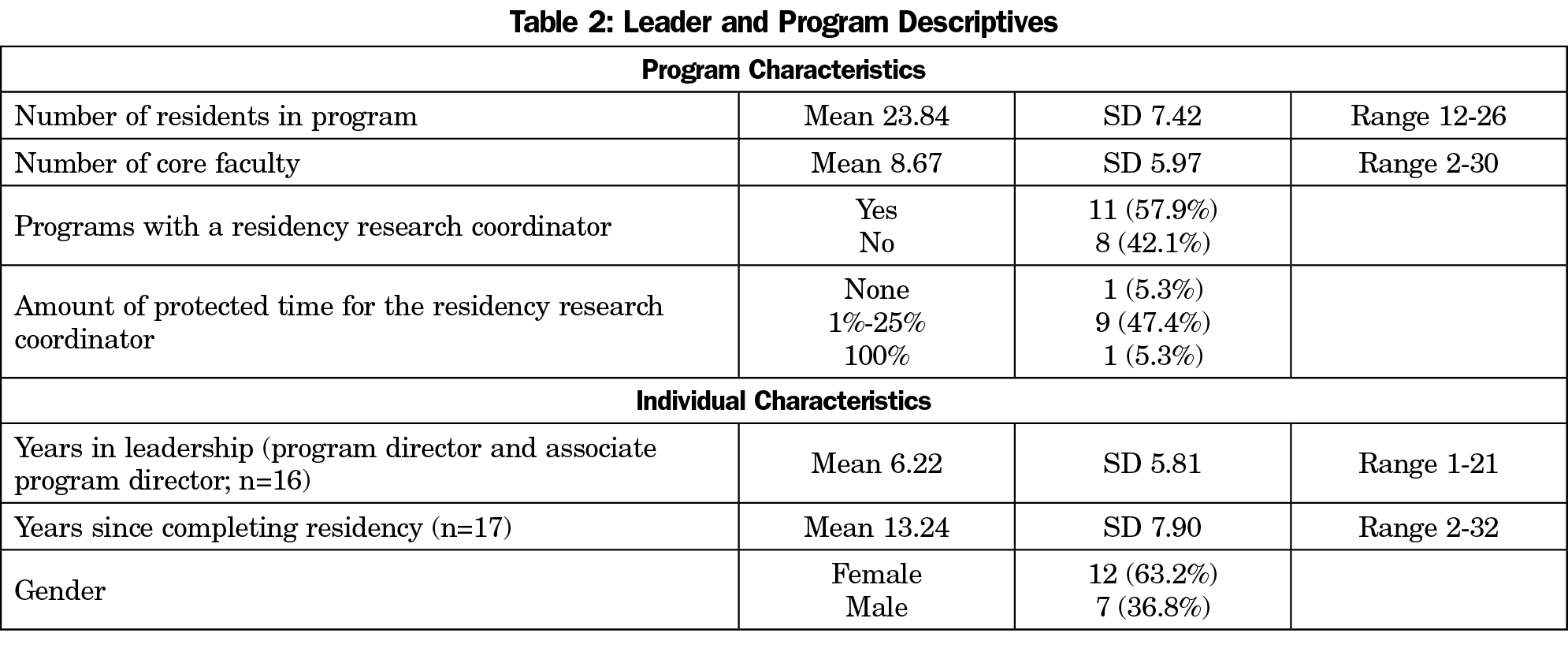

Participants (n=19) were residency program directors or associate program directors. Table 2 presents program and individual characteristics.

Participants provided their own definition of success in scholarship. Leaders described success via production or participation. Some leaders determined success by a product—completed publication; whereas other leaders perceived success through participation in the scholarship process. One leader summarized, “Success being measured then, that all of my third-year residents all participate in a project before they graduate. Success, not necessarily being measured by publication.”

Leaders shared positive attitudes toward scholarship; however, motivations to engage residents and residency faculty in scholarship diverged. Motivations for promoting scholarly activity among participants were extrinsic (through ACGME, program graduation, or promotion requirements) or intrinsic (through personal interest, educational value, and a creative pursuit). Table 3 presents participant descriptions to illustrate perceptions. The intrinsically-motivated leaders encouraged scholarly activity of the value it brings to medicine. Many take part in scholarly activity to appreciate the role it plays in generating literature, which guides patient care guidelines and decisions. This motivation contrasted the extrinsic motivators that drive other leaders. Motivation was not described as a facilitator or barrier.

References to lack of resources (particularly knowledgeable experts, support staff, and time) and uncertainty of “what counts as scholarship” were cited as primary barriers. Participants also cited clinical production incentives as a hindrance to producing scholarly activity.

In the validation check, the six peer checks supported content validity. One leader emphasized,

Being a [program director] is much like being a parent. The Holy Grail of parenting is installing inherent motivation in your children. If … we have installed some inherent motivation towards scholarship whatever the definition is, I have been successful.

Emerging themes illustrate differences in how FMR program leaders perceive the role of scholarship in residency. Participating in scholarly activity due to extrinsic factors can be effective; however, discipline leaders should be aware of its potential long-term effect. The implications of this contrast in motivators can be interpreted through a dual-processing framework. Dual-processing theories suggest that behaviors prompted by intrinsic motivation will be more enduring.25 Conversely, individuals motivated by extrinsic forces may be less inclined to continue efforts after forces are removed. When resources are limited, value-based decision making occurs, and scholarly activity can be pushed to the side. However, if the surrounding environment recognizes scholarly activity as high value, reprioritization efforts will reflect that value. If we aim to cultivate physicians who value evidence, leaders should emphasize the intrinsic motivators of scholarship, consistently communicating to residents the role of scholarship in evidence-based medicine.

A focus-group method enabled us to hear from participants representing a variety of experiences, from varying program types and sizes. Demographic questionnaires were anonymous so we are unable to connect statements to demographics. The research experience of residency leaders themselves may influence motivations, but this information was not collected. Data were collected before July 2019 changes to ACGME common program requirements. However, a change in ACGME requirements does not change this study’s findings that leaders are motivated by extrinsic and intrinsic forces.

The reasons for mandating resident and faculty scholarship must be clearly communicated to affect positive attitudes toward scholarship. Leaders and residents must understand that scholarly activity is an educational process intended to move residents and faculty toward a goal, but it is not the goal itself.

As the number of family medicine residencies increases, the demand for leaders increases as well.26 When selecting leaders, perceptions of the role of scholarship should be a factor. Training programs for new leaders, such as the National Institute for Program Director Development,27 can challenge leaders to think about the motivation for residency scholarship.

Acknowledgments

Disclaimer: The views expressed within this publication represent those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the US Air Force, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Henry M. Jackson Foundation, the Department of Defense, or the US Government, at large.

The authors thank Dr Dean Seehusen for providing insight on an early version of this manuscript.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Family Physicians Inquiries Network.

Presentations: These findings were presented at the 2019 STFM Annual Spring Conference in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

References

- Crawford P, Seehusen D. Scholarly activity in family medicine residency programs: a national survey. Fam Med. 2011;43(5):311-317.

- Philibert I, Lieh-Lai M, Miller R, Potts JR III, Brigham T, Nasca TJ. Scholarly activity in the next accreditation system: moving from structure and process to outcomes. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(4):714-717. doi:10.4300/JGME-05-04-43

- Schein EH. Organizational culture and leadership. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1992.

- Parkerson GR Jr, Barr DM, Bass M, et al. Meeting the challenge of research in family medicine: report of The Study Group on Family Medicine Research. J Fam Pract. 1982;14(1):105-113.

- Culpepper L, Franks P. Family medicine research. Status at the end of the first decade. JAMA. 1983;249(1):63-68. doi:10.1001/jama.1983.03330250043026

- DeHaven MJ, Wilson GR, Murphree DD, Grundig JP. Family practice residency program directors’ views on research. Fam Med. 1997;29(1):33-37.

- Oeffinger KC, Roaten SP Jr, Ader DN, Buchanan RJ. Support and rewards for scholarly activity in family medicine: a national survey. Fam Med. 1997;29(7):508-512.

- Neale AV. A national survey of research requirements for family practice residents and faculty. Fam Med. 2002;34(4):262-267.

- Kruse JE, Bradley J, Wesley RM, Markwell SJ. Research support infrastructure and productivity in U.S. family practice residency programs. Acad Med. 2003;78(1):54-60. doi:10.1097/00001888-200301000-00011

- Young RA, Dehaven MJ, Passmore C, Baumer JG. Research participation, protected time, and research output by family physicians in family medicine residencies. Fam Med. 2006;38(5):341-348.

- Ullrich N, Botelho CA, Hibberd P, Bernstein HH. Research during pediatric residency: predictors and resident-determined influences. Acad Med. 2003;78(12):1253-1258. doi:10.1097/00001888-200312000-00014

- Levine RB, Hebert RS, Wright SM. Resident research and scholarly activity in internal medicine residency training programs. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):155-159. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40270.x

- Seehusen DA, Weaver SP. Resident research in family medicine: where are we now? Fam Med. 2009;41(9):663-668.

- Gill S, Levin A, Djurdjev O, Yoshida EM. Obstacles to residents’ conducting research and predictors of publication. Acad Med. 2001;76(5):477. doi:10.1097/00001888-200105000-00021

- Ledford CJ, Seehusen DA, Villagran MM, Cafferty LA, Childress MA. Resident scholarship expectations and experiences: sources of uncertainty as barriers to success. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(4):564-569. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-12-00280.1

- Lingard L, Zhang P, Strong M, Steele M, Yoo J, Lewis J. Strategies for supporting physician-scientists in faculty roles: a narrative review with key informant consultations. Acad Med. 2017;92(10):1421-1428. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001868

- Seales SM, Lennon RP, Sanchack K, Smith DK. Sustainable Curriculum to Increase Scholarly Activity in a Family Medicine Residency. Fam Med. 2019;51(3):271-275. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.906164

- Seehusen DA, Ledford CJ, Grogan S, et al. A point system as catalyst to increase resident scholarship: an MPCRN study. Fam Med. 2017;49(3):222-224.

- Wood W, McCollum J, Kukreja P, et al. Graduate medical education scholarly activities initiatives: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):318. doi:10.1186/s12909-018-1407-8

- Kichler K, Kozol R, Buicko J, Lesnikoski B, Tamariz L, Palacio A. A structured step-by-step program to increase scholarly activity. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(6):e19-e21. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.08.008

- Robbins L, Bostrom M, Marx R, Roberts T, Sculco TP. Restructuring the orthopedic resident research curriculum to increase scholarly activity. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(4):646-651. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-12-00303.1

- Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007.

- Kidd PS, Parshall MB. Getting the focus and the group: enhancing analytical rigor in focus group research. Qual Health Res. 2000;10(3):293-308. doi:10.1177/104973200129118453

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Research: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Aldine De Gruyter; 1967.

- Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. Communication and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1986. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-4964-1

- American Academy of Family Physicians. 2019 Match Results for Family Medicine. 2019; https://www.aafp.org/medical-school-residency/program-directors/nrmp.html. Accessed July 2, 2019.

- Pugno PA, Dornfest FD, Kahn NB Jr, Avant R. The National Institute for Program Director Development: a school for program directors. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15(3):209-213.

- Training of the physician for family practice: Eleventh report of the Expert Committed on Professional and Technical Education of Medical and Auxiliary Personnel. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1963.

- Frey JJ. A Creation Story. Fam Med. 2017;49(4):270-274.

- Nunemaker JC, Thompson WV, Mixter G, Mayeda I, Tracy R. Directory of approved internships and residencies. 1969.

- Dickinson WP, Stange KC, Ebell MH, Ewigman BG, Green LA. Involving all family physicians and family medicine faculty members in the use and generation of new knowledge. Fam Med. 2000;32(7):480-490.

- Bucholtz JR, Matheny SC, Pugno PA, David A, Bliss EB, Korin EC. Task Force Report 2. Report of the Task Force on Medical Education. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 1):S51-S64. doi:10.1370/afm.135

- Philibert I, Lieh-Lai M, Miller R, Potts JR III, Brigham T, Nasca TJ. Scholarly activity in the next accreditation system: moving from structure and process to outcomes. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(4):714-717. doi:10.4300/JGME-05-04-43

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements. Chicago: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2018.

There are no comments for this article.