On March 17, 2020, the AAMC recommended the temporary suspension of medical student clinical activities due to the COVID-19 pandemic, profoundly changing medical student education. The abrupt cessation of clinical rotations required the rapid evolution of alternatives to traditional medical education. Some of these methods, such as telemedicine, existed but were not widely utilized.1 Other curricula may have been invented de novo to keep students progressing during what turned out to be an extended lockdown. While there are limitations to the new teaching methods such as not being able to physically touch patients,2 there is still optimism among medical educators3,4 who note telemedicine can reach more trainees with one patient. Experience with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2003 demonstrated that some innovations in online medical education were permanently adopted.5 This study examines changes in teaching methods spurred by COVID-19, whether they were perceived as positive learning, and whether they will be adopted for long-term use.

BRIEF REPORTS

Changes in Family Medicine Clerkship Teaching Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Kelly M. Everard, PhD | Kimberly Zoberi Schiel, MD

Fam Med. 2021;53(4):282-284.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2021.583240

Background and Objectives: On March 17, 2020, the Association of American Medical Colleges recommended temporary suspension of all medical student clinical activities due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which required a rapid development of alternatives to traditional teaching methods. This study examines education changes spurred by COVID-19.

Methods: Data were collected via a Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance survey of family medicine clerkship directors. Participants answered questions about didactic and clinical changes made to clerkship teaching due to the COVID-19 pandemic, how positive the changes were, whether the changes would be made permanent, and how prepared clerkship directors were for the changes.

Results: The response rate was 64%. The most frequent change made to didactic teaching was increasing online resources. The most frequent change made to clinical teaching was adding clinical simulation. Greater changes were made to clinical teaching than to didactic teaching. Changes made to didactic teaching were perceived as more positive for student learning than the changes made to clinical teaching. Clerkship directors felt more prepared for changes to didactic teaching than for clinical teaching, and were more likely to make the didactic teaching changes permanent than the clinical teaching changes.

Conclusions: The COVID-19 pandemic caused nearly all clerkship directors to make changes to clerkship teaching, but few felt prepared to make these changes, particularly changes to clinical teaching. Clerkship directors made fewer changes to didactic teaching than clinical teaching, however, didactic changes were perceived as more positive than clinical changes and were more likely to be adopted long term.

Survey

We gathered data as part of the 2020 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine clerkship directors.6 Annual surveys go to clerkship directors of medical schools accredited by Liaison Committee for Graduate Medical Education (US medical schools) or Committee on Accreditation of Canadian Medical Schools (Canadian medical schools). We modified the final draft of survey questions following pilot testing.

We emailed the survey to 147 US and 16 Canadian clerkship directors during June, 2020. Invitations included a personalized letter signed by the presidents of the sponsoring organizations and a link to the survey via SurveyMonkey. Nonrespondents received two weekly requests, a final request 2 days before closing the survey, and a personal email to verify their status as clerkship directors, check accuracy of email addresses, and encourage participation. The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board in approved the study in May, 2020.

Survey Questions

Demographic questions included gender, race, percent protected time, length of clerkship, and whether clerkships were block only. Participants indicated didactic and clinical changes made to clerkship teaching due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the overall extent to which these changes were made. They also answered whether the changes were positive for student learning, whether they felt prepared for the changes, and if they would make the changes permanent. Response choices ranged from 1 to 5, where 1 was “not at all” and 5 was “completely.”

Analyses

Descriptive statistics summarized demographics and changes made to didactic and clinical teaching. We calculated means and standard deviations for the extent to which changes were made, whether the changes were positive, whether clerkship directors felt they were prepared, and whether changes would be permanent. Paired t tests compared didactic teaching to clinical teaching for the extent to which changes were made, changes were positive, changes would be permanent, and clerkship directors were prepared for the changes. Pearson correlations compared whether changes would be permanent to how positive the changes were and how prepared clerkship directors felt.

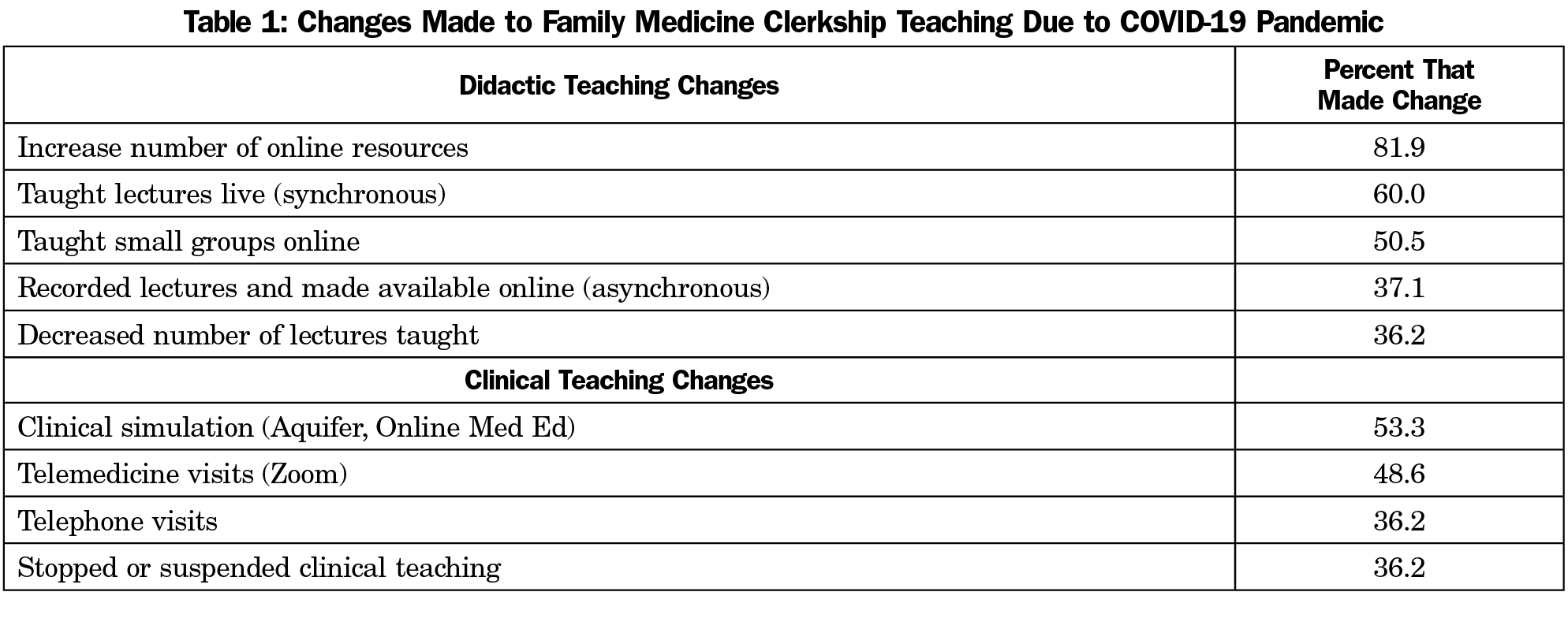

Our response rate was 64.4%, with 105 of 163 clerkship directors responding. Most clerkship directors were female (60%), White (79%), and averaged 31% protected time as clerkship director. Most clerkships (71%) were block only and were either four (41%) or six (34%) weeks long. The most frequent change made to didactic teaching was increasing online resources. The most frequent change made to clinical teaching was adding clinical simulation. Changes made to didactic and clinical teaching are shown in Table 1.

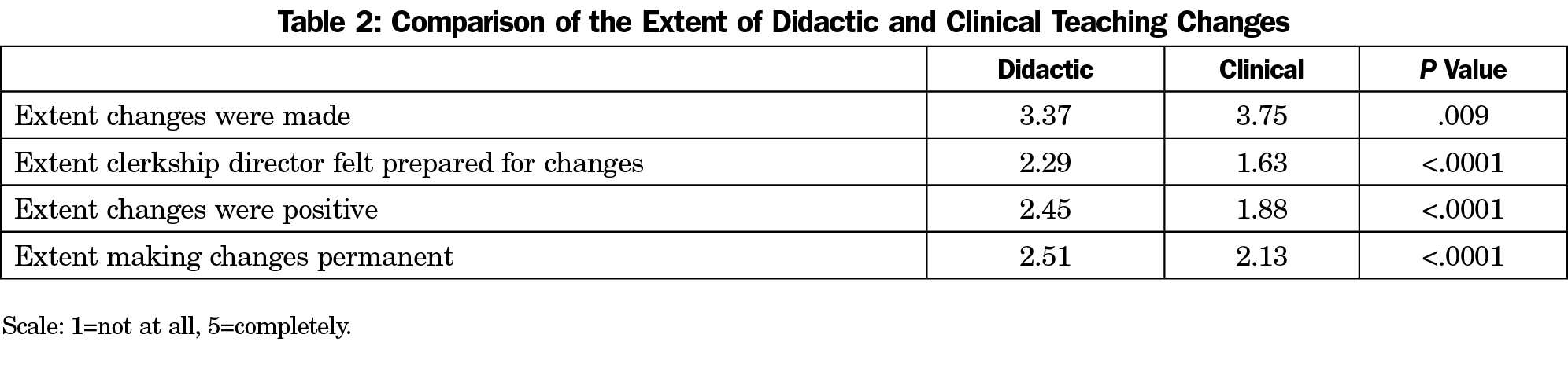

Table 2 displays results from paired t-tests comparing the extent of changes made in didactic teaching to clinical teaching. Clerkship directors made greater changes to clinical teaching than to didactic teaching (P=.009). Changes made to didactic teaching were perceived as more positive for student learning than those made to clinical teaching (P<.0001). Clerkship directors felt more prepared for changes to didactic teaching than for clinical teaching (P<.0001). They were more likely to make the didactic teaching changes permanent than the clinical teaching changes (P<.0001).

Bivariate correlations showed the more positive the changes were for student learning, the more likely they would be made permanent for both didactic teaching (r=.407, P<.0001) and clinical teaching (r=.502, P<.0001). For clinical teaching, the more prepared clerkship director felt to make the changes, the more likely they would be made permanent (r=.205, P=.043). There was no correlation between making changes permanent and preparedness for didactic teaching (r=.066, P=.522).

The COVID-19 pandemic caused nearly all clerkship directors to make changes to clerkship teaching, but few felt prepared to make these changes, particularly to clinical teaching. Clerkship directors made fewer changes to didactic teaching than to clinical teaching. However, didactic changes were perceived as more positive than clinical changes and were more likely to be adopted long term.

Didactic changes may have been easier to make because nascent changes in educational methods to active learning may have facilitated the transition to online learning.7 Many students were already using online resources, most commonly online lectures or question banks.8 Students’ familiarity with simulated patients, during which they often view another student’s interactions via video, may also have helped. COVID-19 may have accelerated use of online modules, which may have better outcomes.9

The changes made to clinical teaching were not surprising, given the AAMC’s mandatory suspension of clinical activities for students. During a pandemic, clinical practices should convert to virtual care,10 as most clerkships did through the adoption of telemedicine and telephone visits. Family physicians, because of their varied experience and breadth of care, are well suited to address rapidly changing needs in patient care and curricula.11,12 The COVID-19 pandemic may have caught clerkship directors off guard, but they will be better prepared for clinical teaching should another suspension occur, by developing curricula for telemedicine and telephone visits. Virtual visits won’t replace in-person visits, but when students can’t be in clinic they can still learn required material and may learn best practices for the future.

Limitations to this study are that we only captured changes made at the time of the survey. Improvements could have been made after an adjustment period, and clinical teaching changes may have improved over time.

The COVID-19 pandemic required educators to make extensive changes to medical student training that they may not have felt prepared for, but it also offered opportunities for growth. Some of the changes were positive for student learning and can be permanently adopted. Now is the time for innovation in both didactic and clinical teaching to prepare students for uncertainty.

References

- Lamba P. Teleconferencing in medical education: a useful tool. Australas Med J. 2011;4(8):442-447. doi:10.4066/AMJ.2011.823

- Woolliscroft JO. Innovation in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis. Acad Med. 2020;95(8):1140-1142. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003402

- Weiner, S. No classrooms, no clinic: medical education during a pandemic.Association of American Medical Colleges. Published April 15, 2020. Accessed October 19, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/no-classrooms-no-clinics-medical-education-during-pandemic.

- Weiner, S. No classrooms, no clinic: medical education during a pandemic. Association of American Medical Colleges. Published April 15, 2020. Accessed October 19, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/no-classrooms-no-clinics-medical-education-during-pandemic.

- Ahmed H, Allaf M, Elghazaly H. COVID-19 and medical education. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):777-778. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30226-7

- Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW. Creating a Centralized Infrastructure to Facilitate Medical Education Research. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257-260. doi:10.1370/afm.2228

- Rose S. Medical Student Education in the Time of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2131-2132. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.5227

- Wynter L, Burgess A, Kalman E, Heron JE, Bleasel J. Medical students: what educational resources are they using? BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):36. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1462-9

- Everard KM, Schiel KZ. Learning outcomes from lecture and an online module in the family medicine clerkship. Fam Med. 2020;52(2):124-126. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.211690

- Krist AH, DeVoe JE, Cheng A, Ehrlich T, Jones SM. Redesigning Primary Care to Address the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Midst of the Pandemic. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(4):349-354. doi:10.1370/afm.2557

- National Clerkship Curriculum, 2nd ed. Leawood, KS: Society of Teachers of Family Medicine;2018; 2nd edition. https://www.stfm.org/media/1828/ncc_2018edition.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2021.

Lead Author

Kelly M. Everard, PhD

Affiliations: Department of Family Medicine, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO

Co-Authors

Kimberly Zoberi Schiel, MD - Department of Family Medicine, Saint Louis University School of Medicine

Corresponding Author

Kelly M. Everard, PhD

Correspondence: Family and Community Medicine, 1402 S Grand Blvd, St Louis, MO 63104. 314-977-8586. Fax: 314-977-5268.

Email: kelly.everard@health.slu.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.