Background and Objectives: Because of the importance of and increasing competition for unpaid community faculty’s time, we qualitatively evaluated the adjunct community faculty experience in order to identify mechanisms to improve the recruitment, training, and retention of these faculty members.

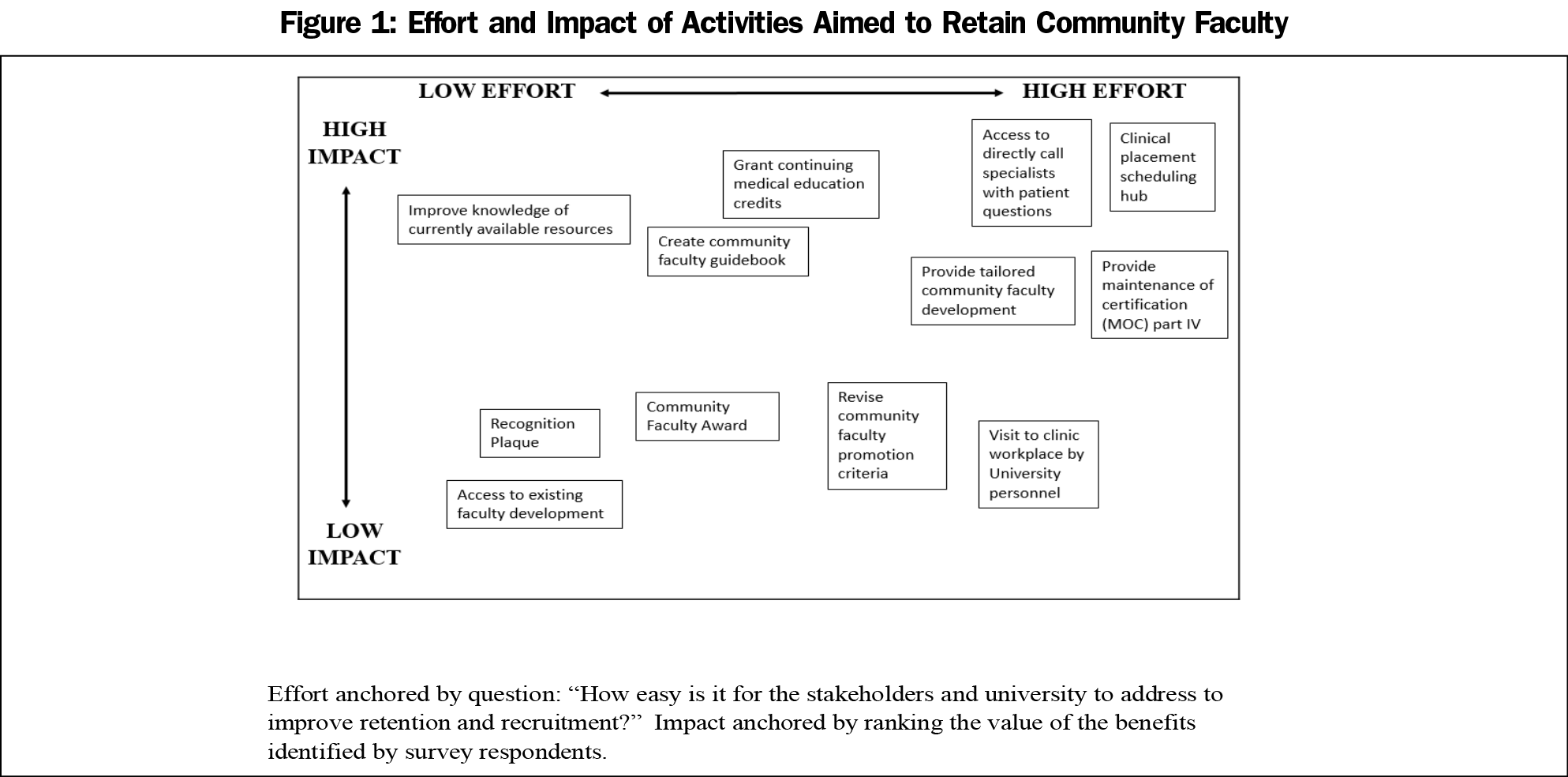

Methods: The authors captured community faculty and key stakeholder opinion through interviews, focus groups, and a survey to elucidate their perspective of roles, responsibilities, facilitators, and barriers for providing quality teaching and learning experiences. After evaluating the data, we created an impact/effort matrix to guide suggested changes.

Results: Key medical education stakeholders reported adjunct community faculty members were critical to delivery of the medical school curriculum and shared methods and barriers for retaining members. Adjunct community faculty focus groups revealed two major themes: (1) personal experience and motivation, and (2) individual advantages and institutional barriers that influence being a faculty member. The survey and impact/effort matrix led to interventions including an Office of Community Faculty to implement recruitment and retention programs and provide more comprehensive oversight, a clinical scheduling hub, improved access to specialists for community faculty, and awards to recognize the critical contributions of community faculty members.

Conclusions: As competition for community placements increases, including community faculty voices to inform action is an effective investment that enables an institution to direct resources towards interventions that maximize their support and engagement. Including community faculty perspectives also increases faculty’s ability to participate in training the next generation of physicians.

US medical schools often rely on volunteer community faculty to teach ambulatory patient care, outside the hospital setting, to medical students and primary care residents.1-3 New medical schools have emerged and existing schools have expanded class sizes in response to the US physician shortage,4 creating concern for academic administrators about a potential shortage of high-quality experiences in primary care.4,5

Studies of ambulatory preceptor motivation have not focused on community faculty,6,7 who may experience decreased clinical productivity while precepting.5,8-11 Allopathic medical schools face competition for clinical placement locations from other health professional schools that provide financial compensation.12 Financial models for most public and some private medical schools cause compensation to be untenable.13 Eighty-five percent or more of medical schools are concerned about clinical training sites and quality clinical preceptors; 41% report compensating community faculty, and 46% percent report concern about losing community faculty if they do not provide compensation.4 In response to these trends, we systematically investigated our ability to recruit and retain community faculty.

Our institutional review board deemed this study nonhuman subject research. We identified community faculty as those who (1) held adjunct faculty appointments, (2) worked with trainees, (3) did not hold a tenure or nontenure track faculty position at the university, and (4) were unpaid by the university.

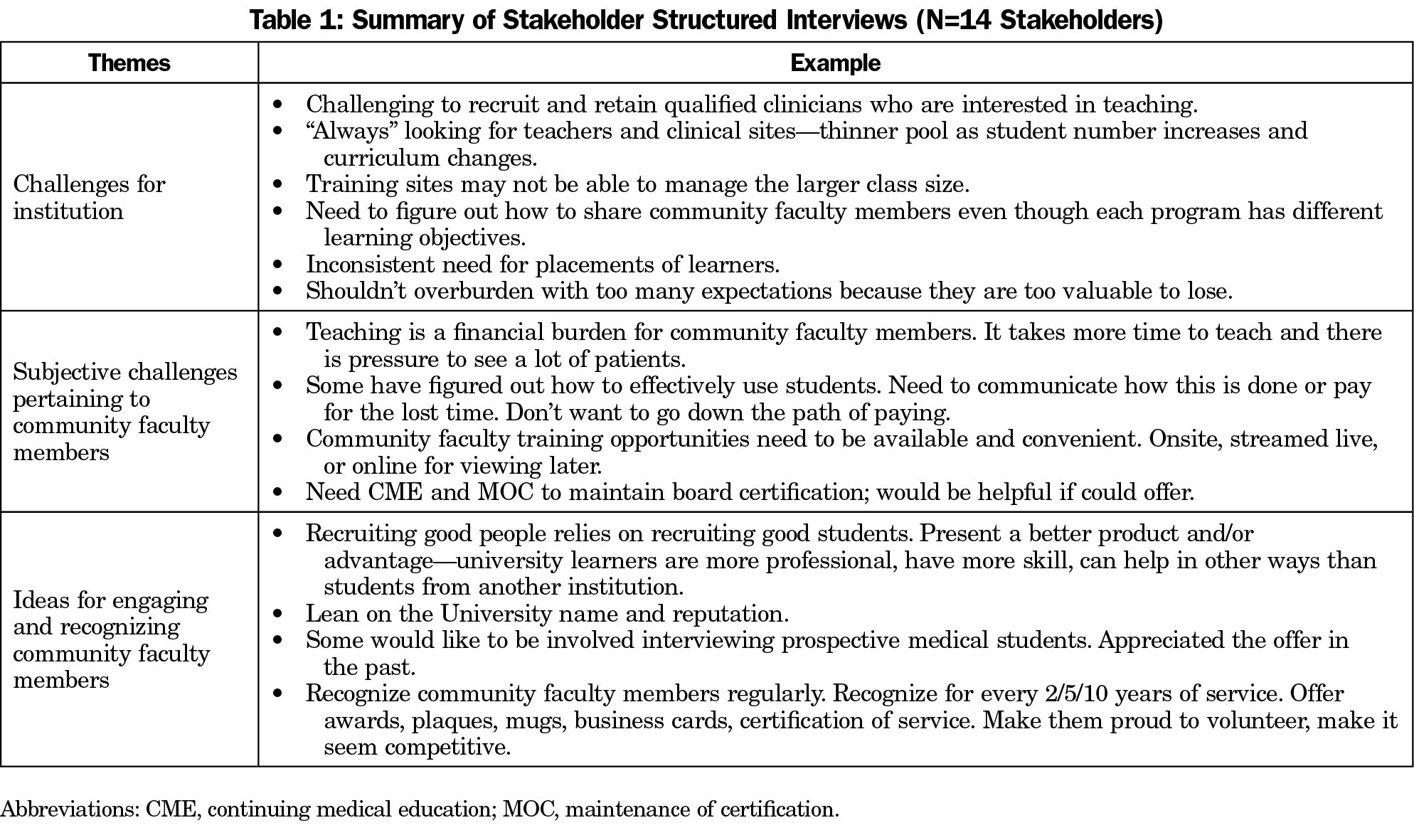

Using a semistructured interview guide, two authors (L.O. and L.W.) conducted stakeholder interviews with education leaders at the institution (associate deans, program directors, clerkship directors, faculty practice leaders). Three authors (L.O., L.W., W.H.) reviewed interview findings to develop themes, using audio recordings for clarification.

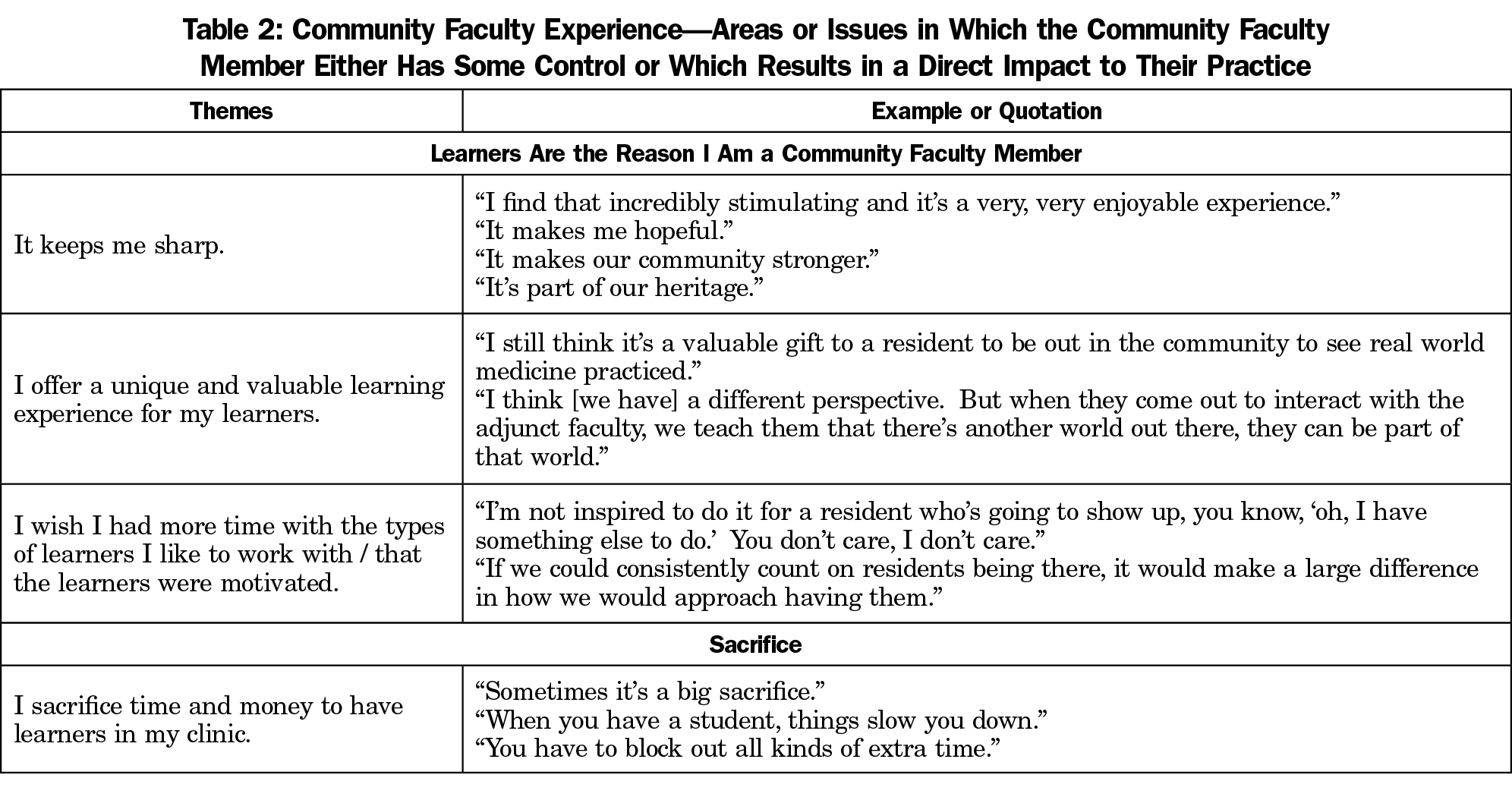

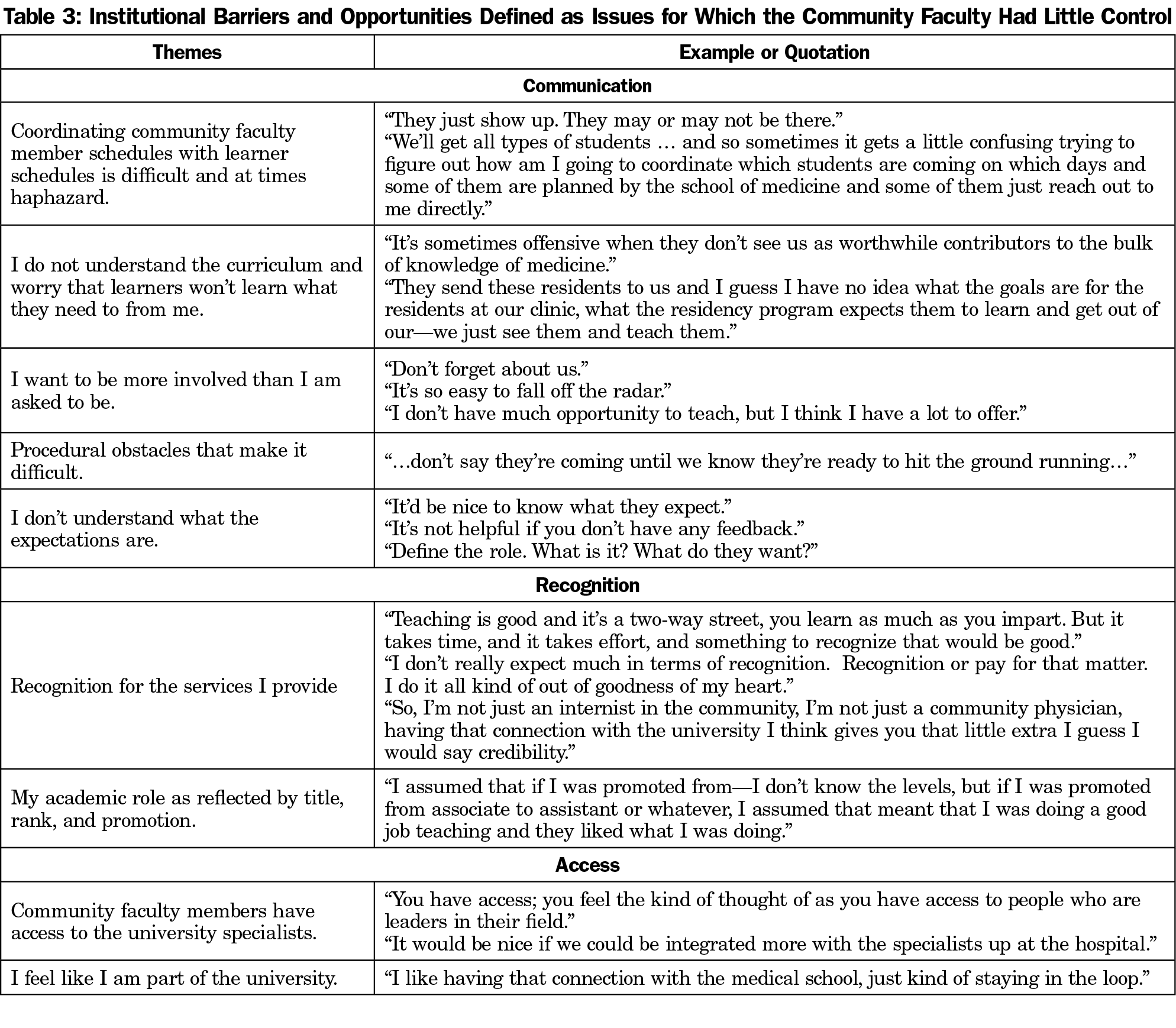

Based on stakeholder interviews, we created a focus group guide to elicit perceptions of roles, value of experience, and actions the medical school could take to enhance community faculty experience. We audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim the 90-minute focus groups. After every focus group, L.O., L.W., and W.H. identified key ideas. We continued the focus groups until no new themes emerged. Managing the data in NVivo 10, L.O., L.W., and W.H. developed a codebook, reviewed and coded transcripts using a thematic approach, discussed coding decisions, and all authors resolved differences through discussion.14

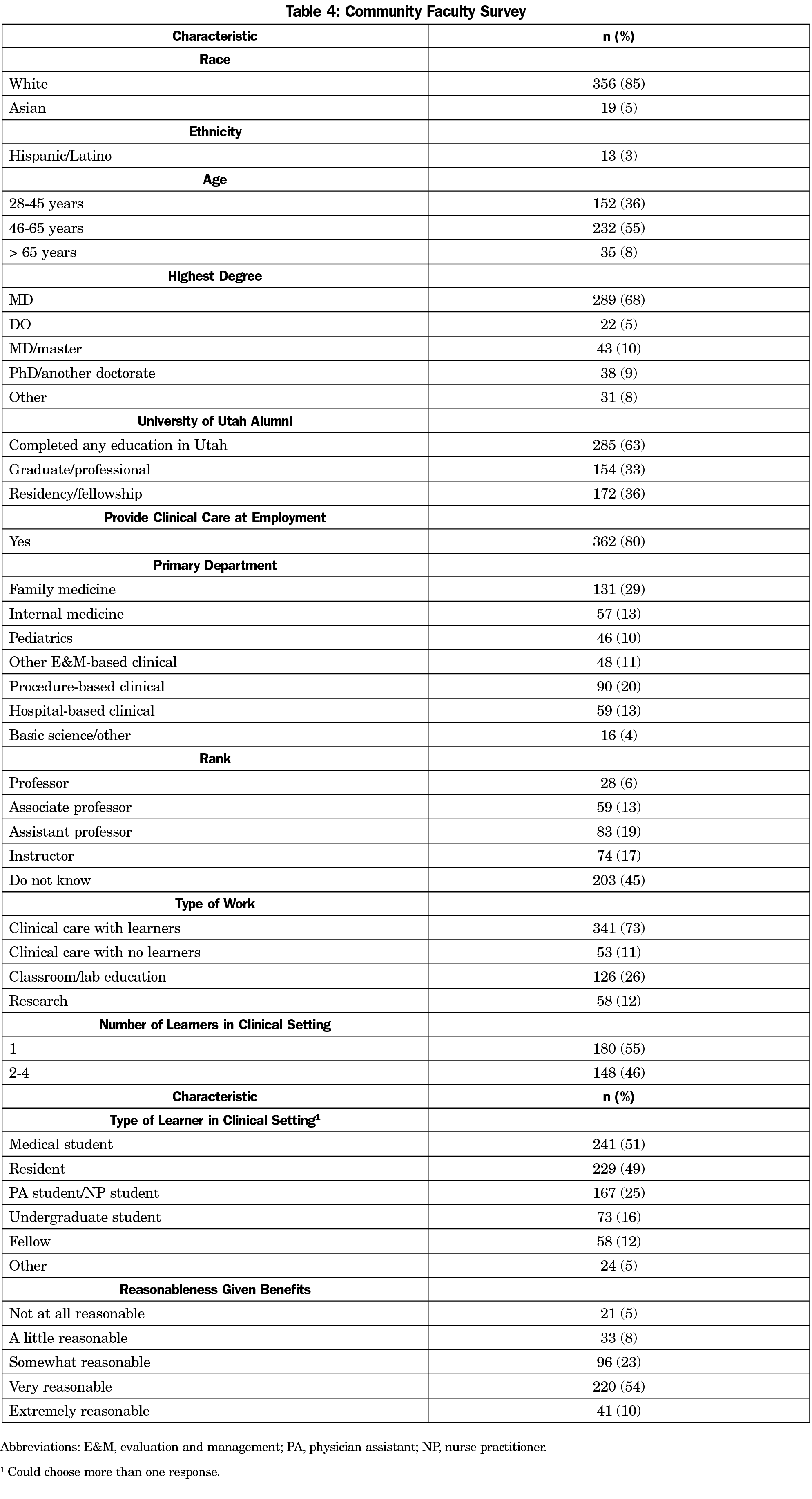

Using the focus groups results, we created a 33-question survey covering demographics, hours of faculty work, communication, promotion, benefits, value, and satisfaction. We identified 1,003 community faculty members to complete the anonymous web-based survey. We used SAS 9.4, for descriptive statistics for distributions and χ2 tests for comparisons.

Authors L.O., H.H., and W.H. triangulated their findings and created an Impact/Effort Matrix,15 which displays institutional effort versus impact of the change on the community faculty, to direct future efforts.

Fourteen key education and system stakeholders participated in the interviews. Stakeholders emphasized the vital importance to the educational mission, identified challenges in recruiting, tracking, and retaining community faculty, and spoke of shared responsibility to prepare students for outpatient experiences (Table 1). Seventy community faculty members participated in nine focus groups, which revealed two themes: (1) community faculty experience (Table 2), and (2) institutional barriers and opportunities (Table 3).

Of 1,003 community faculty surveyed, 468 (46.7%) responded (Table 4). The respondents were representative of the pool. Most were satisfied with the responsibilities, given the benefits received (Table 4). Satisfaction did not vary by respondent age, where they trained, number of learners, time as a community faculty member, or department.

We used the findings, as integrated through the Impact/Effort Matrix (Figure 1) to guide institutional action. We created an Office of Community Faculty and appointed an assistant dean. We addressed communication issues identified by community faculty by distributing an electronic newsletter spotlighting faculty, news, and development opportunities. We also created an online resource guide and support for promotion.

To improve teaching, we adapted existing faculty development programs.5 Targeted curricula include integrating students into a busy practice environment and mitigating financial losses through scheduling. We now offer continuing medical education-accredited synchronous and asynchronous learning opportunities.

Although updating promotion guidelines was deemed low-impact, high-effort, when a large department updated theirs, we assisted. We now notify departments annually of community faculty eligible for promotion.

We recognize community faculty with a community faculty award, supported by a local business and the alumni association. Award winners, chosen with learner input, are featured in the newsletter, alumni magazine, social media, and at commencement.

To increase community faculty access to university specialists and maintenance of certification part IV credit, we partnered with institutional hospital and quality improvement groups. We recently launched a speed consult service via the electronic health record.

Our study’s findings may be limited as it was conducted at a single institution. Some clinical specialties may have been overrepresented and professorial rank may be misreported by faculty.

Education stakeholders clearly articulated the value of community faculty, while community faculty reported both positive and negative experiences. As the need for clinical teaching sites and preceptors outstrips availability, it behooves medical school leadership to demonstrate to community faculty they are valued.1,7 Our findings elucidate areas of focus, including efforts to improve community faculty experience by addressing institutional barriers and enhancing institutional advantages.

Our approach provided community faculty a voice and allowed us to triangulate their thoughts with those of other stakeholders. The majority of stakeholders and community faculty perceive the relationship as mutually beneficial. Consistent with self-determination theory and other studies,6,7 the community faculty were intrinsically motivated. They identified the primary benefits of teaching students as “keeping me sharp,” staying connected to medical advances, and contributing to future generations. Though they encounter financial or workload disincentives, community faculty perceive the overall value of participation as high.7

To preserve the relationship between the medical school and community faculty, institutions should address barriers including scheduling errors, ineffective communication, and lack of recognition. Optimizing scheduling and providing curricular goals and feedback are essential.

The Impact/Effort Matrix was crucial for prioritizing and allowed us to act first on low-effort, high-impact issues, such as highlighting resources and opportunities. We have brought institutional focus to implementation of high-effort, high-impact initiatives. For example, creation of a central clinical placement hub could decrease institutional barriers, and will take substantial investment from multiple institutional stakeholders.

At a time when competition for community placements is increasing, listening to the voices of community faculty members—an indispensable educational resource—produced new resources to support and retain them.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Vivian Lee, whose support made this project possible, Drs Karly A. Pippitt and Terry D. Box for serving as inaugural assistant deans for community faculty, and Raheed Al Dumani, PhD for statistical analysis.

Financial Support: This investigation was supported by the University of Utah Study Design and Biostatistics Center, with funding in part from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant 8UL1TR000105 (formerly UL1RR025764). Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at University of Utah.

References

- Christner JG, Dallaghan GB, Briscoe G, et al. The community preceptor crisis: recruiting and retaining community-based faculty to teach medical students-a shared perspective from the Alliance for Clinical Education. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28(3):329-336. doi:10.1080/10401334.2016.1152899

- Carney PA, Ogrinc G, Harwood BG, Schiffman JS, Cochran N. The influence of teaching setting on medical students’ clinical skills development: is the academic medical center the “gold standard”? Acad Med. 2005;80(12):1153-1158. doi:10.1097/00001888-200512000-00021

- Block SM, Sonnino RE, Bellini L. Defining “faculty” in academic medicine: responding to the challenges of a changing environment. Acad Med. 2015;90(3):279-282. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000575

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Results of the 2017 Medical School Enrollment Survey. 2018. https://members.aamc.org/iweb/upload/Results_of_the_2017_Medical_School_Enrollment_Survey.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2018.

- Denton GD, Griffin R, Cazabon P, Monks SR, Deichmann R. Recruiting primary care physicians to teach medical students in the ambulatory setting: a model of protected time, allocated money, and faculty development. Acad Med. 2015;90(11):1532-1535. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000778

- Latessa R, Colvin G, Beaty N, Steiner BD, Pathman DE. Satisfaction, motivation, and future of community preceptors: what are the current trends? Acad Med. 2013;88(8):1164-1170. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829a3689

- Minor S, Huffman M, Lewis PR, Kost A, Prunuske J. Community preceptor perspectives on recruitment and retention: the CoPPRR Study. Fam Med. 2019;51(5):389-398. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.937544

- Vinson DC, Paden C. The effect of teaching medical students on private practitioners’ workloads. Acad Med. 1994;69(3):237-238. doi:10.1097/00001888-199403000-00020

- Baldor RA, Brooks WB, Warfield ME, O’Shea K. A survey of primary care physicians’ perceptions and needs regarding the precepting of medical students in their offices. Med Educ. 2001;35(8):789-795. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00980.x

- Ellis J, Alweis R. A review of learner impact on faculty productivity. Am J Med. 2015;128(1):96-101. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.09.013

- Grayson MS, Klein M, Lugo J, Visintainer P. Benefits and costs to community-based physicians teaching primary care to medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(7):485-488. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00139.x

- Halperin EC, Goldberg RB. Offshore medical schools are buying clinical clerkships in US hospitals: the problem and potential solutions. Acad Med. 2016;91(5):639-644. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001128

- Koharchik L. Supporting adjunct clinical faculty. Am J Nurs. 2017;117(9):58-62. doi:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000524551.58567.c6

- Richards L. Handling qualitative data : a practical guide. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2015.

- Andersen B, Fagerhaug T, Beltz M. Impact effort matrix. American Society for Quality in Healthcare. https://journals.stfm.org/primer/2020/kost-2020-0081. Published 2018. Accessed December 9, 2018.

There are no comments for this article.