Background and Objectives: Wellness in residency has come to the forefront of national graduate medical education initiatives. Exponential growth in knowledge and skill development occurs under immense pressures, with physical, mental, and emotional stressors putting residents at burnout risk. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requires programs to attend to resident wellness, providing the structure, environment, and resources to address burnout. This study’s purpose was to evaluate the Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine online Physician Well-being Course (PWC) with incoming postgraduate year-1 (PGY-1) residents in multiple residencies across a single health care system. The PWC teaches the learner strategies for building resilience, managing stress, identifying signs of burnout, and mindfulness practices including a self-selected daily 10-minute resiliency activity (meditation, gratitude journaling, and finding meaning journaling) for 14 days.

Methods: Incoming PGY-1 residents were enrolled in PWC 1 month prior to 2018 orientation. Validated measures of resiliency, burnout and gratitude were completed pre- and postcourse. We assessed pre/postcourse changes with paired t tests. We asked participants whether they incorporated any wellness behavior changes postcourse.

Results: Almost two-thirds of the incoming trainees completed the course (n=53/87, 61%). We found significant improvements (P<.05) for resiliency and burnout (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization). Gratitude did not change. The personal accomplishment burnout scale declined. The most frequently reported wellness behaviors were in the area of sleep, exercise, and diet.

Conclusions: Resiliency, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization improved, personal accomplishment declined, while gratitude remained the same. This project demonstrates an accessible and scalable approach to teaching well-being to incoming residents.

Resident well-being is at the forefront of national graduate medical education initiatives. Medical students often enter residency with high levels of burnout.1 Burnout is a well-established residency problem; rates range from 27% to 75% across specialties.2,3 The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires residency programs to address resident well-being and provide structure, environment, and resources to support physician well-being.4

Individual-focused interventions and organizational strategies decrease burnout.5 Work hour restrictions, self-care workshops, and a meditation intervention improve burnout.6 Resilience7,8 and mindfulness9 are associated with decreased burnout. However, burnout is not a phenomenon that occurs in isolation. Systemic factors including clerical burden, inefficient clinical practices, and electronic health record challenges contribute. Work-life imbalance, poor morale, challenging patient populations, and unrealistic expectations also contribute.10 Wellness behaviors11 and wellness-promoting activities10 can be implemented to reduce burnout. These factors cannot be ignored when developing a comprehensive plan to improve physician well-being and must be approached collaboratively within the system.12 The Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine (AWCIM) created and investigated the impact of an online, interactive, self-paced, well-being course (https://integrativemedicine.arizona.edu/education/physician_wellbeing.html). As course creators, we hypothesized that 4.5 hours of well-being curriculum distributed online, to multiple residencies in a single health care system at residency start, could improve resiliency, offering residents tools to prevent future burnout.

Setting and Participants

The AWCIM Physician Well-being Course (PWC) was offered to all incoming PGY-1 residents at the University of Arizona, College of Medicine Tucson in June 2018.

Intervention

Residents were enrolled in PWC 1 month prior to orientation, with support from the designated institutional officials and graduate medical education well-being subcommittee. Participation was voluntary. The 4.5-hour online course teaches foundations of well-being (sleep, nutrition, exercise, resiliency, and mindfulness), and includes a 2-week daily, self-selected, 10-minute, resiliency activity. Participants complete precourse self-assessments, reflecting on their results. Strategies for building resilience, managing stress, preventing burnout, and developing mindfulness practices are explored.

After completing the coursework, residents select a resiliency activity (meditation, gratitude journaling, or finding meaning journaling). Weekly emails remind them to continue their daily activity, returning after 2 weeks for postcourse self-assessments. Participants view their pre- and postcourse self-assessments. We requested completion by July 1, 2018, with a 30-day grace period. The University of Arizona Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Measures

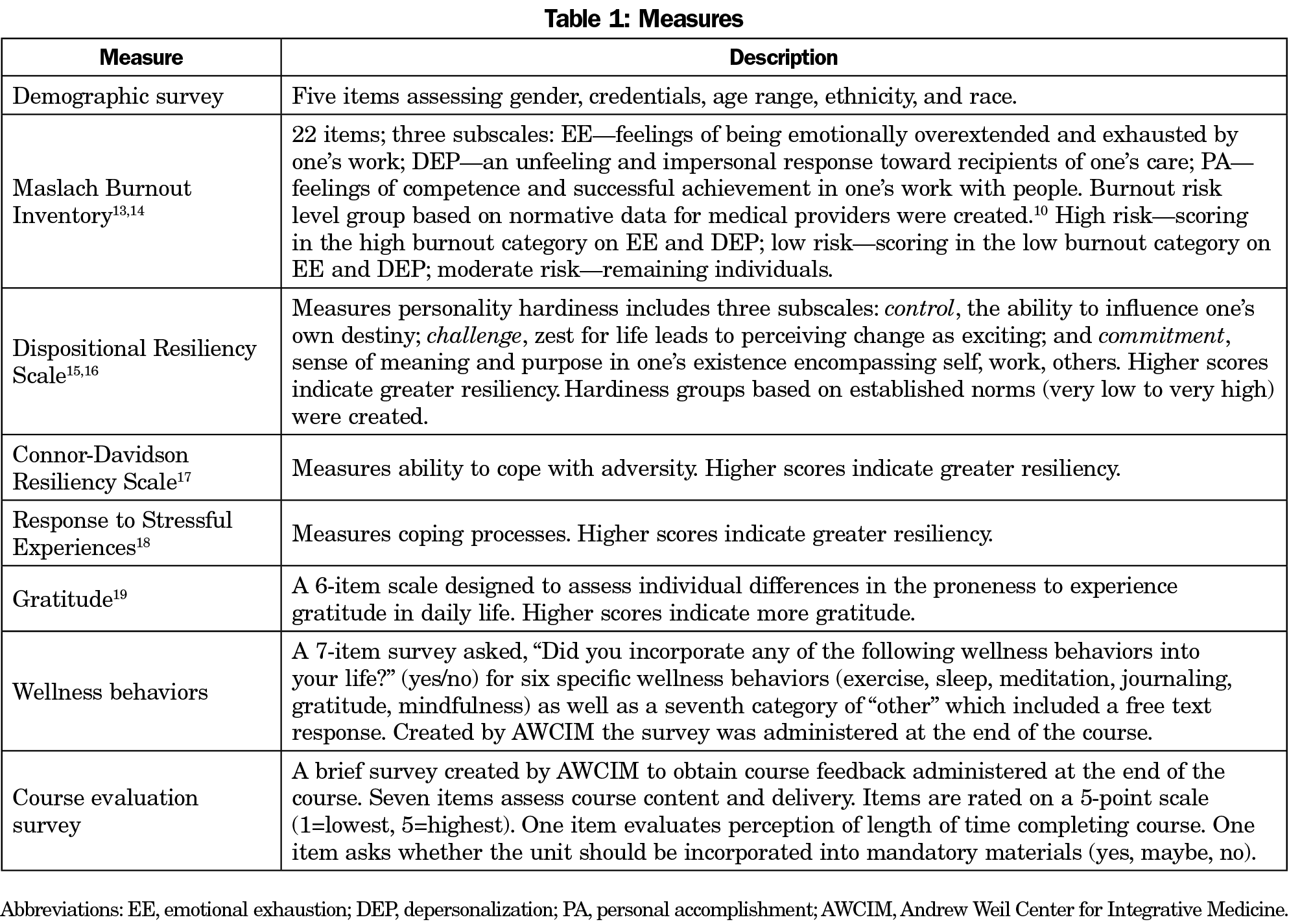

Validated burnout,13,14 resiliency,15-18 and gratitude19 measures were administered pre/postcourse. We administered wellness behavior and course evaluation surveys developed by AWCIM postcourse (Table 1). We deidentified measures for analysis.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented for completion, wellness behaviors, and course evaluation results. We conducted paired t tests to assess pre/post changes on burnout, resiliency, and gratitude measures. We conducted χ2 analyses on the demographic, categorical resiliency (hardiness), and burnout measures. We conducted analyses using IBM SPSS Statistics Desktop V25.0 (Armonk, New York).

Sample Characteristics and Completion Rates

Eighty-seven residents from 15 specialties (Table 2) were enrolled and 53 completed the course (61%). There were no differences in demographic characteristics between completers and noncompleters.

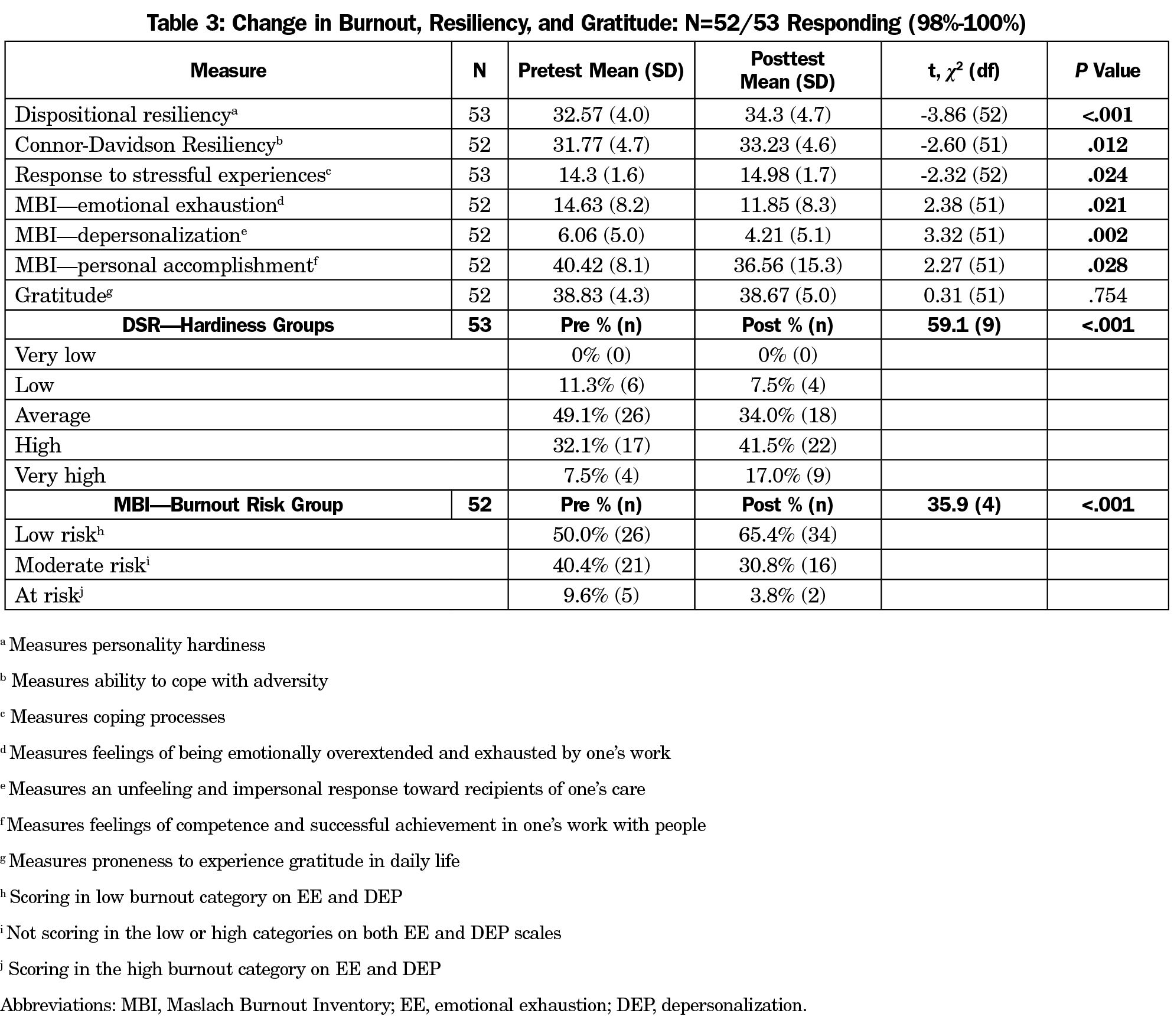

Impact on Burnout, Resiliency, Gratitude, and Wellness Behaviors

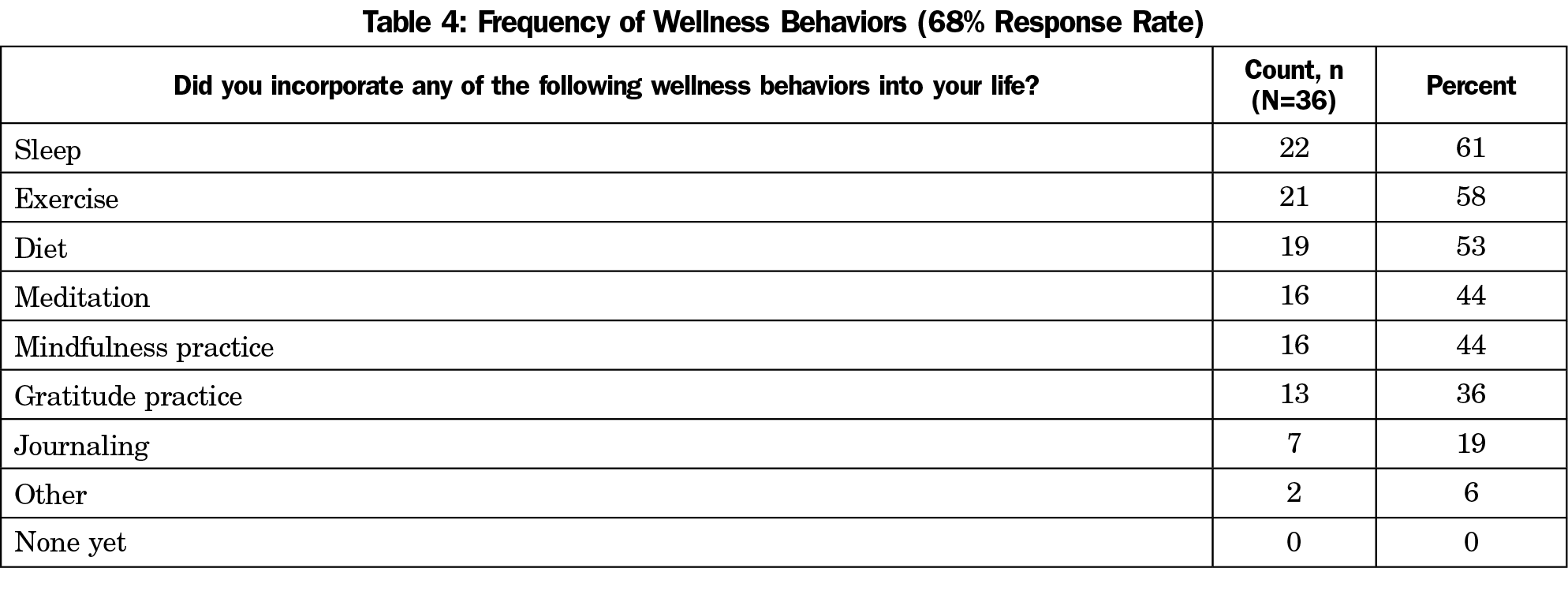

We observed statistically significant improvements in emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and resiliency (Table 3). Resiliency increased while emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment decreased. At posttest the number of participants in the high/very high hardiness categories increased, while participants in the average/low categories decreased. The number of participants in the low-risk burnout group increased. Participants in the moderate and high-risk groups decreased. The most frequently selected resiliency activity was meditation (n=36/53, 68%). The most frequently reported wellness behavior was sleep.

Course Evaluation

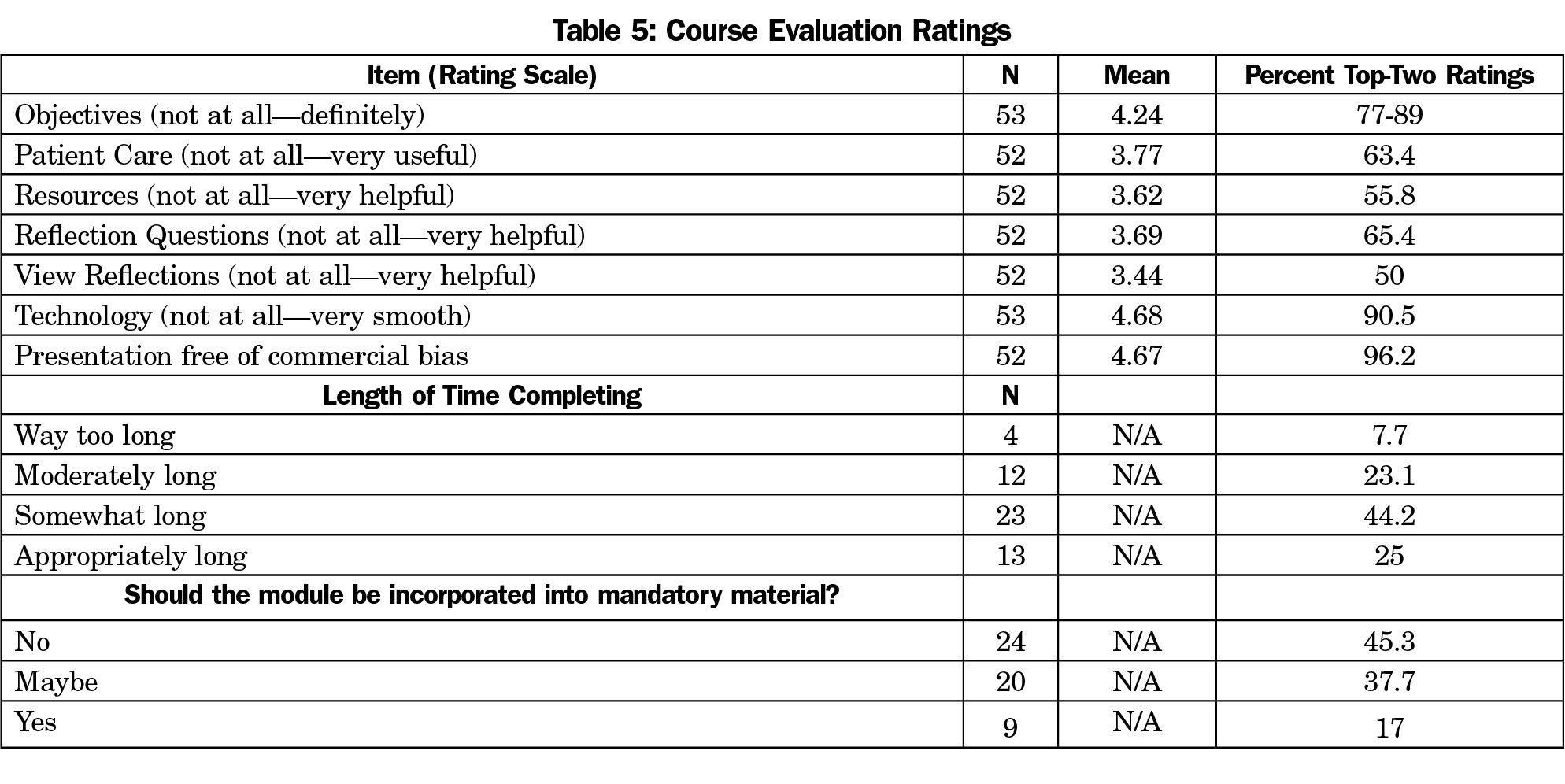

Smoothness of technology, free of commercial bias, and met objectives received the highest ratings (Table 5); while course delivery and usefulness ratings were between neutral and helpful/useful. One-half thought the course should definitely/maybe be incorporated into mandatory material (n=29/53, 55%), with most (n=39/52, 75%) indicating that less time could have been devoted to activity.

This brief, online course teaching foundational well-being and resiliency skills increased self-reported resiliency and decreased burnout inventory scores in incoming residents. PWC provides introductory knowledge about personal well-being, burnout, and resiliency skills. Positive preventive skills learned in this course can be employed with challenging experiences during training.

Course completion was high (61%). Massive open online course completion rates tend to be low (1%-52%, median 13%).20 Very few students (22%) who intended to complete an online course actually completed one.21 One key strategy for our high completion rate was offering PWC prior to residency. Previously, we offered PWC to all resident years during fall 2016; despite having strong programmatic interest and high enrollment, completion was low. Offering the course during onboarding captures trainees in transition during a period when they have additional time and energy. Timing may have adversely affected perceived usefulness of the course as residency training brings up different sources of stress and increased burnout. While offering the course to incoming interns is a limitation, fourth-year medical students and incoming interns demonstrate significant burnout rates.22

Residents self-reported incorporating wellness behaviors, suggesting a possible impact extending beyond well-being knowledge. Personal accomplishment scores declined. It may be difficult for new residents to answer questions regarding personal accomplishment prior to starting residency. Gratitude scores did not change significantly, likely due to the high pretest scores.

Study limitations include the lack of control group or comparison intervention and the inability to confirm the extent to which participants adhered to their resiliency activity. Also, there is no follow-up data to assess whether the reported behaviors and resiliency gained were maintained under the stress of residency. The study results are guiding PWC review to include content regarding the systemic aspects of burnout in health care and methods to capture follow-up assessments to determine if benefits are sustained.

An online course designed to teach residents about well-being and resiliency skills was distributed to all incoming PGY-1 residents. Participants scored higher on resiliency and lower on burnout scales upon completion. Limitations include the lack of control group, timing, and absence of follow up. While cost may be a barrier for some institutions, PWC is a scalable, asynchronous online course, making it an accessible strategy to meet ACGME well-being requirements.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all the residents and fellows participating in the Well-being in Residency study and the Designated Institutional Officials, Dr Conrad Clemens and Dr Victoria Murrain, and the Graduate Medical Education Well-being Subcommittee who supported this initiative. The authors also thank Janice Curtis for her invaluable assistance enrolling course participants and preparing this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors were involved in writing and creating the course that was studied in this paper as employees of the Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine.

Ethical Approval: The University of Arizona Institutional Review Board granted approval for this study.

Presentations: This study was partially reported at the 9th Annual Integrated Medicine for the Underserved (IM4US) Annual Conference, August 22-24, 2019, Santa Clara, CA.

References

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among US medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-451. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134

- Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T. A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med Educ. 2016;50(1):132-149. doi:10.1111/medu.12927

- Ishak WW, Lederer S, Mandili C, et al. Burnout during residency training: a literature review. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(2):236-242. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-09-00054.1

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements Section VI with Background and Intent. 2017. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_Section%20VI_with-Background-and-Intent_2017-01.pdf. Accessed January 16, 2019.

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-2281. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X

- Busireddy KR, Miller JA, Ellison K, Ren V, Qayyum R, Panda M. Efficacy of interventions to reduce resident physician burnout: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(3):294-301. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00372.1

- Buck K, Williamson M, Ogbeide S, Norberg B. Family physician burnout and resilience: a cross-sectional analysis. Fam Med. 2019;51(8):657-663. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.424025

- Reed S, Kemper KJ, Schwartz A, et al. Variability of burnout and stress measures in pediatric residents: an exploratory single-center study from the pediatric resident burnout-resilience study consortium. J Evid Based Integr Med. 2018;23:2515690X18804779.

- Lebares CC, Guvva EV, Ascher NL, O’Sullivan PS, Harris HW, Epel ES. Burnout and stress among US surgery residents: psychological distress and resilience. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(1):80-90. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.10.010

- Ofei-Dodoo S, Callaway P, Engels K. Prevalence and etiology of burnout in a community-based graduate medical education system: a mixed-methods study. Fam Med. 2019;51(9):766-771. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.431489

- Lebensohn P, Dodds S, Benn R, et al. Resident wellness behaviors: relationship to stress, depression, and burnout. Fam Med. 2013;45(8):541-549.

- Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA. 2017;317(9):901-902. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.0076

- Maslach C. Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory. 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

- Maslach C, Jackson SE. Maslach Burnout Inventory. Copyright 1981, 2016.

- Bartone PT. Test-retest reliability of the dispositional resilience scale-15, a brief hardiness scale. Psychol Rep. 2007;101(3 Pt 1):943-944. doi:10.2466/pr0.101.3.943-944

- Bartone PT, Ursano RJ, Wright KM, Ingraham LH. The impact of a military air disaster on the health of assistance workers. A prospective study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989;177(6):317-328. doi:10.1097/00005053-198906000-00001

- Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20(6):1019-1028. doi:10.1002/jts.20271

- De La Rosa GM, Webb-Murphy JA, Johnston SL. Development and validation of a brief measure of psychological resilience: an adaptation of the response to stressful experiences scale. Mil Med. 2016;181(3):202-208. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00037

- Mccullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82(1):112-127. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112

- Jordan K. Massive open online course completion rates revisited: assessment, length and attrition. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning. 2015;16(3). doi:10.19173/irrodl.v16i3.2112

- Reich J. MOOC Completion and Retention in the Context of Student Intent. Educause Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2014/12/mooc-completion-and-retention-in-the-context-of-student-intent. Published 2014. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- Hansell MW, Ungerleider RM, Brooks CA, Knudson MP, Kirk JK, Ungerleider JD. Temporal trends in medical student burnout. Fam Med. 2019;51(5):399-404. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.270753

There are no comments for this article.