“Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane.”

—Dr Martin Luther King, Jr

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

Teaching About Racism in Medical Education: A Mixed-Method Analysis of a Train-the-Trainer Faculty Development Workshop

Jennifer Edgoose, MD, MPH | Joedrecka Brown Speights, MD | Tanya White-Davis, PsyD | Jessica Guh, MD | Katura Bullock, PharmD | Kortnee Roberson, MD | Jessica De Leon, PhD | Warren Ferguson, MD | George W. Saba, PhD

Fam Med. 2021;53(1):23-31.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2021.408300

Background and Objectives: Curriculum addressing racism as a driver of inequities is lacking at most health professional programs. We describe and evaluate a faculty development workshop on teaching about racism to facilitate curriculum development at home institutions.

Methods: Following development of a curricular toolkit, a train-the-trainer workshop was delivered at the 2017 Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference. Preconference evaluation and a needs assessment collected demographic data of participants, their learning communities, and experience in teaching about racism. Post-conference evaluations were completed at 2- and 6-month intervals querying participants’ experiences with teaching about racism, including barriers; commitment to change expressed at the workshop; and development of the workshop-delivered curriculum. We analyzed quantitative data using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software and qualitative data, through open thematic coding and content analysis.

Results: Forty-nine people consented to participate. The needs assessment revealed anxiety but also an interest in obtaining skills to teach about racism. The most reported barriers to developing curriculum were institutional and educator related. The majority of respondents at 2 months (61%, n=14/23) and 6 months (70%, n=14/20) had used the toolkit. Respondents ranked all 10 components as useful. The three highest-ranked components were (1) definitions and developing common language; (2) facilitation training, exploring implicit bias, privilege, intersectionality and microaggressions, and videos/podcasts; and (3) Theater of the Oppressed and articles/books.

Conclusions: Faculty development training, such as this day-long workshop and accompanying toolkit, can advance skills and increase confidence in teaching about racism.

The United States is riddled with shocking and inhumane racial and ethnic health and health care disparities. Teaching health care professionals to address these inequities has typically focused on disparity statistics, cultural competence, and social determinants of health. This approach has failed to address the more intransigent problems that contribute to health disparities in the United States, such as poverty, institutionalized racism and sexism, sociopolitical disenfranchisement, limited educational attainment, residential segregation, and structural vulnerability and violence.1-3 Further, it contributes to misconceptions of race as a biologic construct, ignores clinician implicit bias, neglects historical and structural context, and exacerbates stereotype threat among learners who are underrepresented in medicine. Despite consistent and extensive evidence about pervasive gaps in morbidity and mortality among racial and ethnic groups,4 there is often little to no discussion of the role of racism as a contributor to these gaps.

Many well-intentioned educators have invoked cultural competency as a remedy. The Liaison Committee for Medical Education (LCME)5 and the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)6 have either focused entirely or placed a strong emphasis on curricular development in “cross-cultural medicine,” which may or may not include content on the role of race and/or racism in society. One systematic review of 34 cultural competency training programs for health professionals found only 6% incorporated concepts of racism, bias, or discrimination.7

While social determinants of health (SDOH) are increasingly seen as drivers of health outcomes and inequities, many SDOH educational approaches in medicine focus on the lack of resources, rather than on systems and behaviors that perpetuate inequitable resource distribution. This creates a focus upon content, rather than actionable skills.2 Lessons from other academic disciplines (eg, critical race studies, sociology, economics, anthropology) demonstrate an overdue need to embrace structural competency in medical education,1 which can lead to meaningful, innovative, and compassionate strategies to combat social inequities. Racism is perhaps the most challenging and poorly addressed SDOH.

Learners now demand curricula on racism.8 David Acosta, the chief diversity and inclusion officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges, challenges faculty to acquire not only knowledge but also skills in confronting racism as a critical SDOH that affects patients, learners, health care providers, and educators.9 Practical guidance acquiring such skills is severely lacking. Resources and support are often inadequate to successfully integrate issues of racism and inequities, and to manage the emotional tensions that often arise.10 Such a curriculum requires not just content knowledge, but also demands introspection on the part of both learner and facilitator.

In order to address complex issues of race, power, privilege, and identity, one must develop skills that facilitate open dialogue, preserve safety, and address conflicts in hope of achieving new perspectives, insights, and understanding. To provide clinical learners with curricula that address structural competencies, faculty development is a necessary but neglected step.11 To this end, members of the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) Group on Minority and Multicultural Health met in 2015 to develop curricula that went beyond teaching about race and health disparities to embrace a more complex discourse on racism and health inequities. The group developed and assembled the Toolkit for Teaching About Racism in the Context of Persistent Health and Healthcare Disparities,12 which included facilitator resources and curricular activities that study team members were piloting at their home institutions. In 2016, the study team piloted a 1.5-hour workshop attended by over 120 participants that sampled an activity in the toolkit. Participants reported statistically significant changes in attitude and knowledge regarding their understanding of issues of racism and in their personal commitment to address them.13 In response to the request for more training by participants, the study group expanded this work into a daylong interactive faculty development preconference workshop that incorporated guidance for facilitation of complex conversations of identity and oppression and further explored application of the toolkit by demonstrating four toolkit activities. We hypothesized that with expanded training on supportive self-reflection, guidance on skills for complex conversations, live demonstration and skills practice, and a compendium of knowledge resources, participants would be more willing and able to develop curriculum around structural competence, focusing particularly on racism. We created a train-the-trainer workshop to provide participants an approach to teaching about racism in medical education and then followed up with them on their experience of doing so in their home institutions.

The daylong preconference workshop, “Teaching About Racial Justice: A Train-the-Trainer Faculty Workshop,” was held at the 2017 STFM Annual Meeting. Its goals were to promote participants’ facilitation of complex conversations around identity and racism; ask participants to reflect on personal bias and privilege through experiential and reflective learning, engage participants to deconstruct and explore racism in their home institutions, and practice skills to counter microaggressions experienced across the health care spectrum by patients, learners, and themselves. STFM workshop participants typically consist of educators from family medicine residencies and departments around the United States. Preconference participants were required to register in advance for a full-day preconference of the STFM Annual Spring Conference, that included an additional registration fee. STFM limited registration to 60 participants. In preparation for the workshop, participants completed two Implicit Association Tests (IATs): the race IAT and one additional IAT of their choosing (https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/).

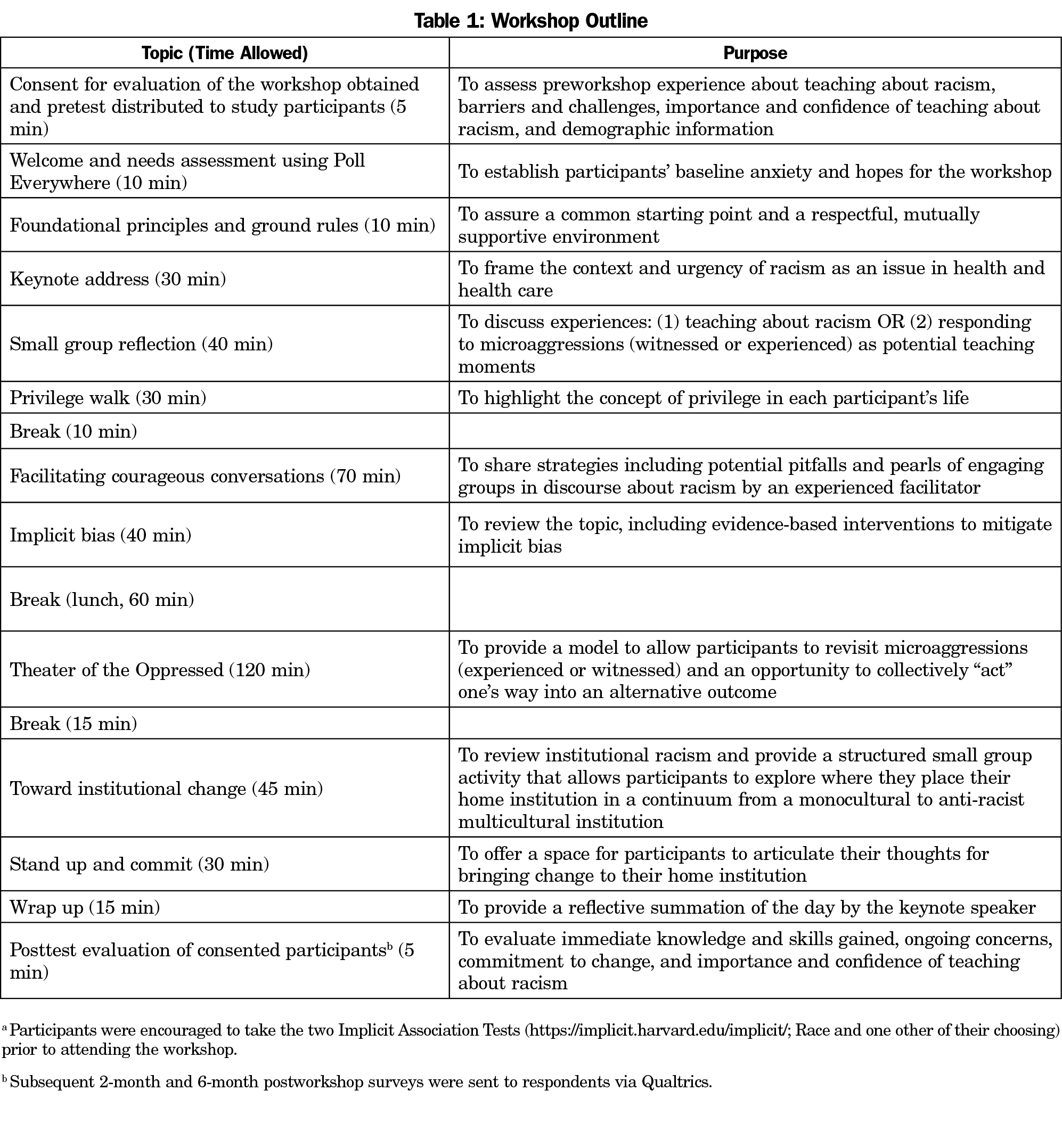

Table 1 outlines a descriptive agenda of the workshop. An initial needs assessment using an audience response system called Poll Everywhere assessed baseline hopes, fears, and goals of participants at the start of the workshop and was captured using free text with only one response per question. Description of the specific activities (eg, Privilege Walk, Theater of the Oppressed) completed during the workshop can be found in the Toolkit for Teaching about Racism in the Context of Persistent Health and Healthcare Disparities.12 Facilitators assigned to each table of participants took notes for the activities that involved small group discussions that were then available for qualitative analysis.

The study group reviewed participant responses to Poll Everywhere for major themes, beginning with independent open coding. The group used a constant comparison approach in which members articulated their perceptions of key conceptual themes. They discussed their notes and built consensus on identified themes. The group performed coding using written methods to articulate themes and conceptual relationships and then edited the written document using selective coding to solidify major themes and organize pertinent concepts within thematic groups.

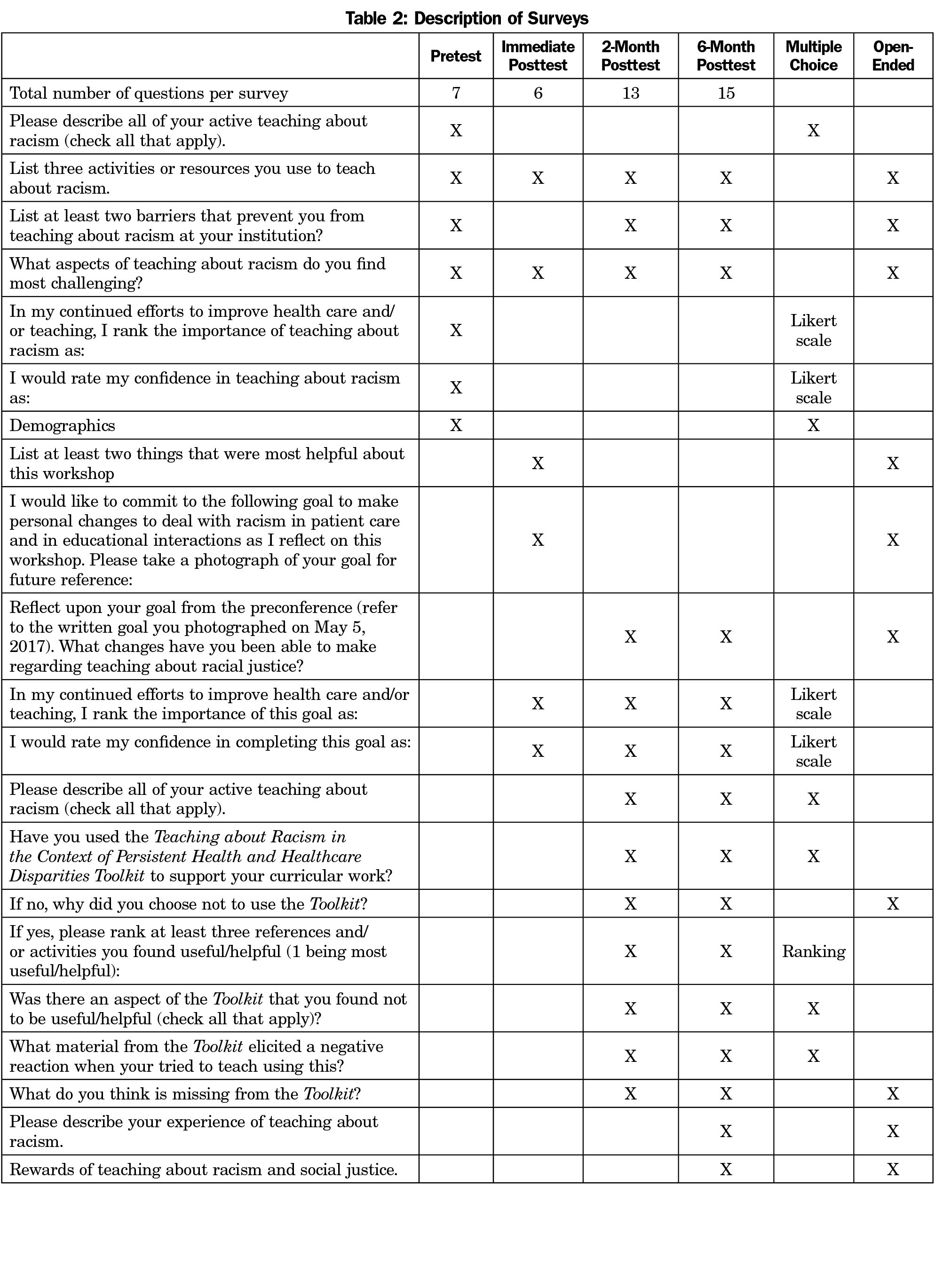

The evaluation of the workshop included written data collected through self-administered surveys (Table 2) during the workshop (pre- and immediate post-), and postworkshop surveys via Qualtrics (Provo, UT) at 2- and 6-months. Each participant provided a unique personal identifier consisting of the last two numbers of their zip code and the last two numbers of their mobile phone number, enabling pairing of pre- and posttest surveys. Pretest surveys collected demographic data of the individual participants, their learning communities, and a description of any activities or resources (if any) that participants used to teach about racism. Both pre- and posttest surveys included questions regarding participants’ experiences teaching about racism, including barriers and challenges. The 2- and 6-month posttest surveys also reviewed the application of the toolkit and reflection on participants’ commitment to change as expressed at the end of the workshop. Completion of each survey took 5 to 10 minutes. Participants received one reminder email if no response was received within 2 weeks.

The study team summarized participant demographics; analyzed pre- and postsurvey results to assess change in knowledge, attitudes, and behavior and uptake/impact of the toolkit using the same coding approach as above; and conducted content analyses of postworkshop survey comments to identify the most salient barriers and challenges to teaching about racism and to guide the prioritization of the next steps. Content analysis methodology described by Downe-Wamboldt uses a descriptive approach in coding of the data and its interpretation of quantitative counts of the thematic codes.14,15 We used this method in this study to illuminate themes in the qualitative data and highlight meaningfulness across a broad group. It allowed for identification of themes in the data, rather than using preconceived categories to describe and quantify anticipated barriers and challenges. This is useful because existing theory in teaching about racism in medical education is limited. Two members of the author team independently applied a constant comparison approach to identify, solidify, and organize major concepts into thematic groups. A third member of the author team was available to resolve any discrepancies. We counted the number of times the concept appeared and divided it by the total number of responses in that group to give a quantitative value to the themes. Additionally, pre/postsurveys were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Florida State University granted this study human subjects approval on April 7, 2017—HSC # 2017 20534.

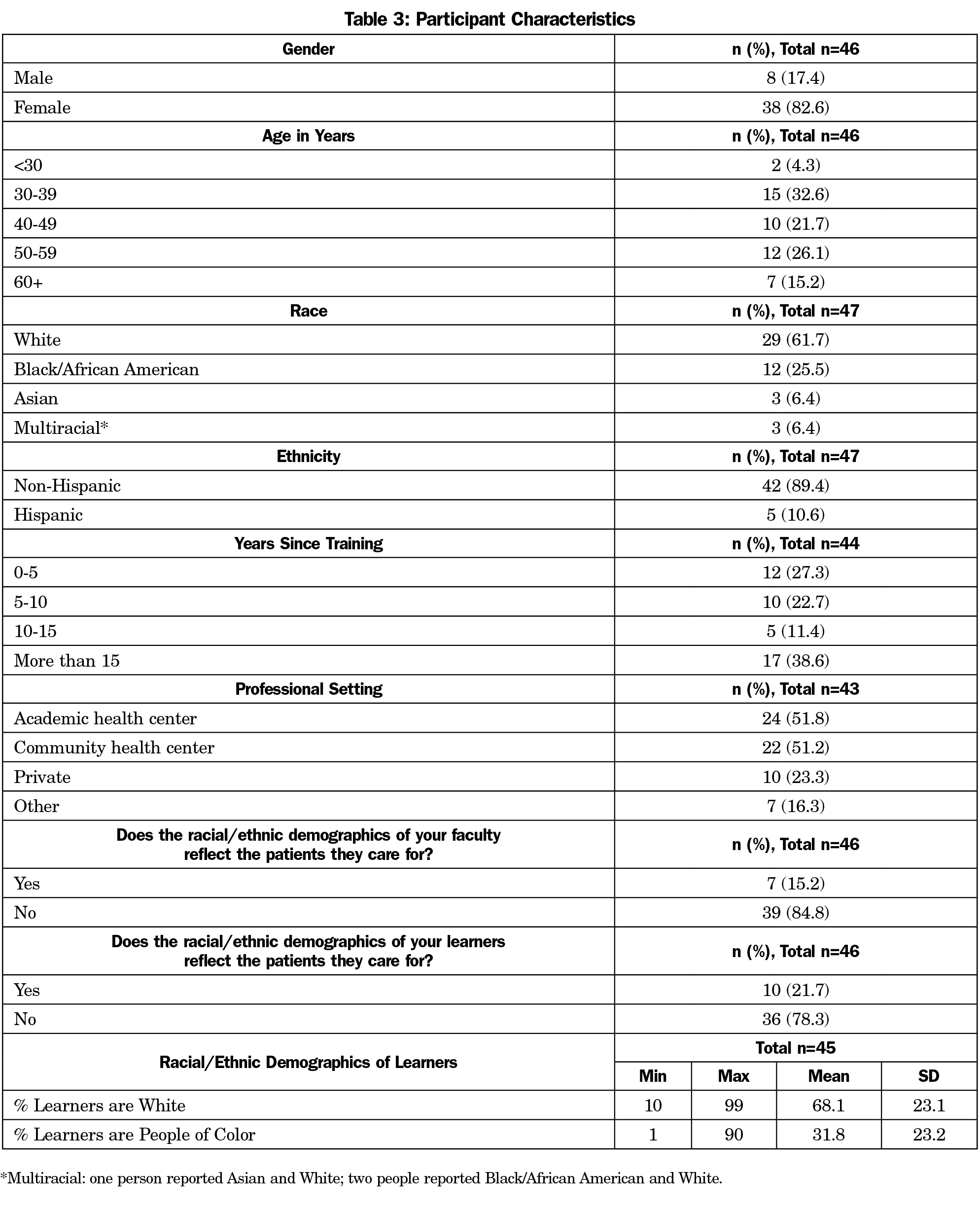

Demographics (Table 3)

Forty-nine people consented to participate in the evaluative survey study. The majority of participants were women (83%, n=38), identified as white (62%, n=29), and between the ages of 30 and 59 years (80%, n=37). Most participants reported that their own race/ethnicity and that of their learners differed from the race/ethnicity of their patients, (85%, n=10; and 78%, n=36, respectively).

Needs Assessment (Table 4)

The Poll Everywhere questions, asked at the outset of the preconference workshop, revealed anxiety, worry, and a strong interest in obtaining skills to employ at their home institutions.

Pre/Postsurveys

All 49 participants completed a pretest survey. Immediately following the workshop, participants who completed any part of the survey were counted in a response rate of 94% (n=46). Postsurvey response rates at 2 months and 6 months following the workshop were 47% (n=23) and 49% (n=24), respectively. Each person did not respond to every question on the pre- and postworkshop surveys. The surveys consisted of close-ended and Likert questions as well as free-text open-ended questions.

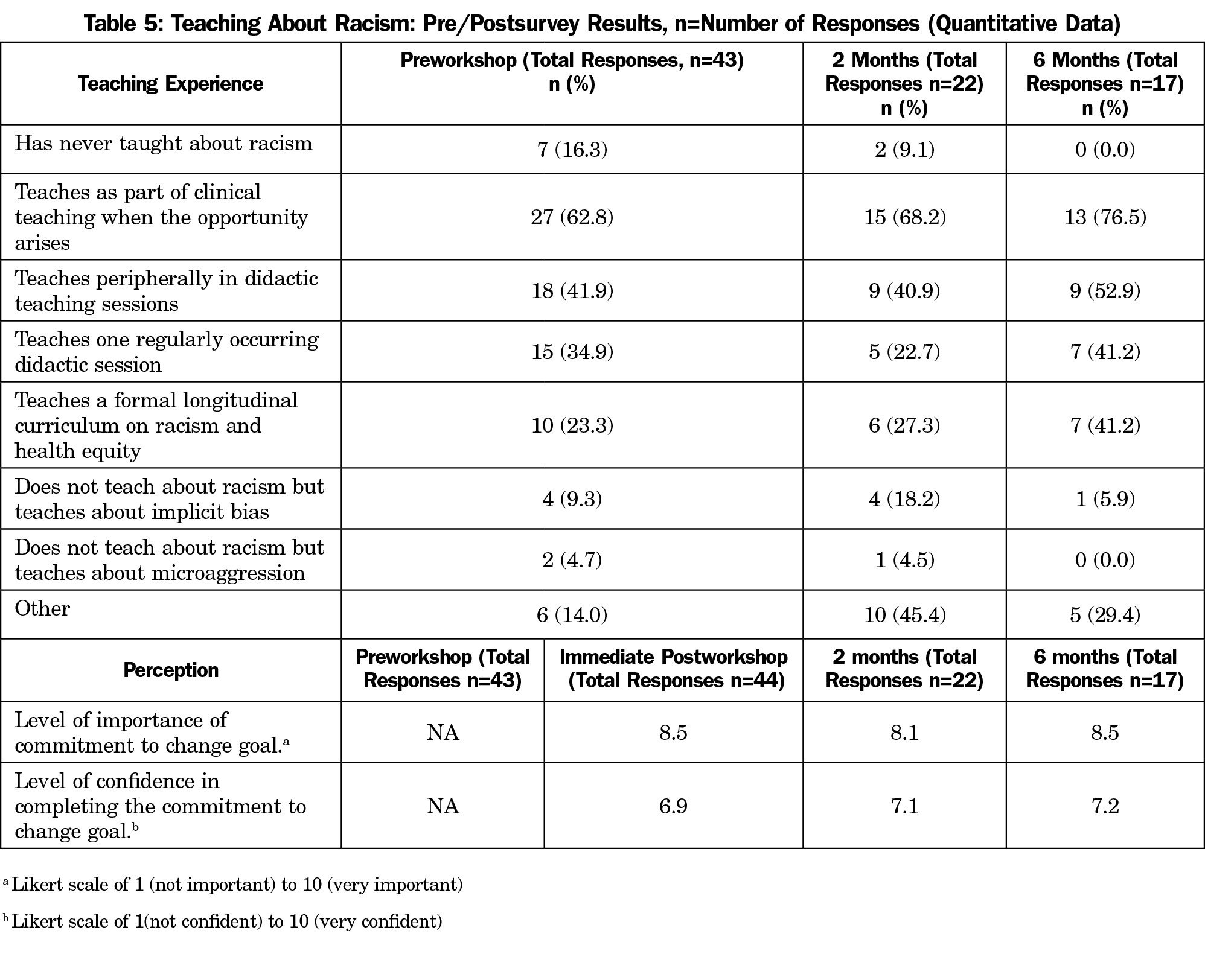

Table 5 shows how participants reported their own teaching about racism prior to the workshop and at 2 months and 6 months. Only 96% (n=43) respondents completed this portion of the survey immediately after the workshop, which decreased to 48% (n=22) and 37% (n=17), respectively, for the 2- and 6-month surveys. Due to the limited data, we were unable to compute a correlation or paired t test. The association between the 2- and 6-month tests regarding importance and confidence in commitment, however, suggests that use of the toolkit and feelings of importance and confidence were likely to persist over this time period. Furthermore, while variability in respondents at these time points limited longitudinal analysis, no respondent at 6 months had “never taught about racism.”

Posttest survey Likert responses revealed a consensus as to the importance of teaching about racism throughout the 6-month study period, with improved confidence in teaching about racism after the workshop (Table 5).

In the free-text comments, participants described that they had engaged in formal discussions with their department faculty on racism and health equity; had joined or created committees on diversity, equity and inclusion; had developed new curricula that included lectures and workshops; and incorporated pieces of the STFM training into their precepting of clinical learners. Participants found responses to their new teaching very positive, although one experienced backlash.

Participants identified that the most rewarding aspects about their increased involvement in teaching about racism included influencing learners’ perspectives (“Encouraging students to be more politically engaged”), collaborating with colleagues (“Working with [a] diverse group of faculty in developing a workshop,” “Finding allies to help with this work”), and professional and personal growth (“Becoming a better educator,” “In it for the long run,” “Being comfortable in my discomfort,” “I am a better person”).

Toolkit Use and Impact

Of the respondents who provided input about whether or not they had used the toolkit, the majority reported using it at 2 months and 6 months (61%, n=14/23; and 70%, n=14/20, respectively). While formal statistical analysis was limited by the amount of data, the association between the 2- and 6-month tests regarding use of the toolkit suggests that application of the toolkit continued over this time period. Participants found the “definitions/developing common language” portion of the toolkit most helpful at 2 months, and “exploring implicit bias” section most helpful at 6 months with “definitions/developing common language” as the second-most helpful tool at that time. Some commented on challenges related to systemic issues of racism and implicit bias, and discomfort in exploring privilege, intersectionality, and microaggressions. Other challenges included facilitating the Theatre of the Oppressed and the Privilege Walk exercises found in the toolkit with mixed resident and faculty participants.

Challenges to Teaching About Racism

Participants were asked about challenges to teaching about racism in medical education. Their postsurvey comments (n=291) were categorized into the following categories, listed in descending order of frequency: (1) institutional (49%, n=143); (2) educator (21%, n=62); (3) communication (10%, n=30); (4) societal/cultural (10%, n=30); and (5) learner (9%, n=26).

The most common institutional barriers were time constraints on teaching (28.0%, n=40) and issues regarding the curriculum (28.0%, n=40). Time constraints stemmed from the lack of specified time in the curriculum for inclusion and discussion, lack of flexibility in learners’ schedules, lack of time to develop curricula or prepare content, and lack of time to have meaningful in-depth discussions and debriefing sessions. Issues with curricula that created barriers included conflicting priorities in already overcrowded content the lack of a formal curriculum, discontinuity in both the curricular content and the availability of students, and a lack of teaching tools and resources.

The most common educator barriers reported were lack of knowledge, expertise, or experience (29.0%, n=18); lack of partners or collaborators (16.1%, n=10); educator discomfort (11.3%, n=7); and a feeling of lack of credibility to discuss racism because of educators’ own race and/or gender (11.3%, n=7; ie, individuals from nonpersecuted categories felt they could not facilitate discussions about oppression).

The most common communication barriers reported focused on a lack of knowledge or skill to present the topic of racism (70%, n=21; eg, not knowing the right language to use or how to communicate with individuals with diverse backgrounds, experiences, and perspectives). Other barriers included lack of safe, supportive environments for dialogue, and the need for more voices and perspectives to be included in the conversation.

A broad range of societal/cultural issues surfaced, with the most reported barriers being the difficulty of the topic and strong emotions surrounding the topic of racism (40%, n=12) and ignoring or denial of racism as an issue (26.7%, n=8).

Learner barriers included learner discomfort and sensitivity discussing racism (30.8%, n=8), student disinterest (23.1%, n=6), the diversity of learners (19.2%, n=5), and student pushback and resistance (11.5%, n=3).

Future health professionals need highly skilled faculty who can effectively teach about the impact of racism on health and health care. To begin addressing this need, a daylong faculty development workshop was conducted to provide resources, strategies and experiential learning about how to develop and teach antiracism curriculum. Follow-up surveys with the participants identified that the two most significant barriers to teaching about racism in medical education are institutional (lack of time and prioritization) and educator-related (lack of knowledge, skills, and partners). A major theme from the responses was relief at being given structured faculty development that included not only content, but also concrete examples of educational activities and facilitation training in a safe and nurturing environment. Increasing such opportunities is critical to address the issue, as major barriers to implementation are lack of curricula and anxiety around how to manage conflict or uncomfortable conversations about racism.8 Given the system- wide dearth of underrepresented in medicine faculty, any expectations that these individuals will lead antiracism curriculum development may lead to anxiety, exhaustion, and their decreased promotion and retention. Nurturing allies who are skilled in this work is an important strategy to overcome this challenge.16

The Toolkit for Teaching About Racism in the Context of Persistent Health and Healthcare Disparities is an important first step toward providing formal curricula. We encourage educational and professional organizations to develop and make available vetted, transportable curricula that may someday help drive development of competencies and metrics related to teaching about racism and systems of inequity.

Participants’ experiences in teaching about racism included discussions and dialogue, forming committees and workgroups, curriculum development, and professional growth and commitment. Educators have found many rewards, including influencing students, collaborating with colleagues, and professional and personal growth. Although this workshop primarily impacted participants individually, at a structural level, participants also identified action-oriented opportunities and activities for institutional change.

Generalizability of these results is limited by a number of factors. Participants self-selected the workshop, but notably, curricular change in home institutions will be aided by faculty who are already motivated to do this teaching. Participant data were all self-reported, and thus only from their perspective on such issues as learner barriers, institutional barriers, and degree to which they actually implemented the toolkit. As there was no control group, we could not assess the specific role that our intervention played in any curricular changes. Generalizability is also limited by variability in participants’ settings. Finally, the sample size was small, and not all who participated answered all of the questions in the postworkshop survey, and an even smaller proportion of participants completed the 2-month and 6-month postworskhop surveys. Nonetheless, reports of barriers and toolkit application by those who completed all postworkshop surveys may reflect real issues faced by faculty committed to implementing this work.

Faculty development training such as this daylong workshop and accompanying toolkit as we have described, can promote learning skills and increase confidence in teaching about racism. Although more sustained faculty development is needed, workshops that provide such intensive, concrete training can make an important difference.16

Health equity is achievable.17,18 We will only realize this goal when institutions and faculty are intentional about their teaching. Teachers and learners must value all people, rectify historical injustices, and provide resources according to need.19

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the leadership and wisdom of Dr Denise Rodgers and Dr David Henderson, the support of our cofacilitator Dr Adrienne Hampton, the advocacy and mentorship of Dr Jeffrey Ring and Dr Kathryn Fraser, the statistical support by Dr Henry Carretta, and the editorial direction and encouragement of Dr Mindy Smith. Dr Edgoose also acknowledges her mother Hyun Joo “Judy” Choe, who fled a war-torn country joining the diaspora of transcontinental migrants and optimists who make up our nation’s great melting pot. She lived out the American dream, seeing her three children become successful champions of social justice, and sharing the last quiet days of her life with the lead author as this manuscript was completed.

References

- Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:126-133. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.032

- Sharma M, Pinto AD, Kumagai AK. Teaching the social determinants of health: a path to equity or a road to nowhere? Acad Med. 2017.

- Willen SS. Confronting a “big huge gaping wound”: emotion and anxiety in a cultural sensitivity course for psychiatry residents. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2013;37(2):253-279. doi:10.1007/s11013-013-9310-6

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States. In: Brief. 2016. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistic; 2015.

- Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Standard 7. In: Functions and structures of a medical school. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2017 .http://lcme.org/publications/. Accessed July 20, 2019.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements. https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Common-Program-Requirements. Accessed July 20, 2019.

- Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, et al. Cultural competence: a systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Med Care. 2005;43(4):356-373. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000156861.58905.96

- Brooks KC. A piece of my mind. A silent curriculum. JAMA. 2015;313(19):1909-1910. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.1676

- Acosta D, Ackerman-Barger K. Breaking the silence: time to talk about race and racism. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):285-288. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001416

- Chávez NR. The Challenge and benefit of the inclusion of race in medical school education. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;3(1):183-186. doi:10.1007/s40615-015-0147-2

- Gordon WM, McCarter SA, Myers SJ. Incorporating antiracism coursework into a cultural competency curriculum. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;61(6):721-725. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12552

- Anderson A, Brown Speights JS, Bullock K, Edgoose J, Ferguson W, Fraser K, Guh J, Hampton A, Henderson D, Lankton R, Martinez-Bianchi V, Ring J, Roberson K, Rodgers D, Saba GW, Saint-Hilaire L, Svetaz V, White-Dave T, Wu D. Toolkit for teaching about racism in the context of persistent health and healthcare disparities. STFM Resource Library. https://connect.stfm.org/HigherLogic/System/DownloadDocumentFile.ashx?DocumentFileKey=cf40991e-96e9-3e15-ef15-7be20cb04dc1&forceDialog=0. Accessed July 14, 2019.

- White-Davis T, Edgoose J, Brown Speights JS, et al. Addressing racism in medical education: an interactive training module. Fam Med. 2018;50(5):364-368. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.875510

- Downe-Wamboldt B. Content analysis: method, applications, and issues. Health Care Women Int. 1992;13(3):313-321. doi:10.1080/07399339209516006

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

- Wu D, Saint-Hilaire L, Pineda A, et al. The efficacy of an antioppression curriculum for health professionals. Fam Med. 2019;51(1):22-30. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.227415

- Fry-Johnson YW, Levine R, Rowley D, Agboto V, Rust G. United States black:white infant mortality disparities are not inevitable: identification of community resilience independent of socioeconomic status. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(1 Suppl 1):S1-131-135.

- Brown Speights JS, Goldfarb SS, Wells BA, Beitsch L, Levine RS, Rust G. State-level progress in reducing the black-white infant mortality gap, United States, 1999-2013. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(5):775-782. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.303689

- Jones CP. Systems of power, axes of inequity: parallels, intersections, braiding the strands. Med Care. 2014;52(10)(suppl 3):S71-S75. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000216

Lead Author

Jennifer Edgoose, MD, MPH

Affiliations: Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI

Co-Authors

Joedrecka Brown Speights, MD - Department of Family Medicine and Rural Health, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL

Tanya White-Davis, PsyD - Department of Family and Social Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center-Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY.

Jessica Guh, MD - Swedish Family Medicine Residency Cherry Hill, International Community Health Services, Seattle, WA

Katura Bullock, PharmD - Department of Pharmacotherapy, University of North Texas System College of Pharmacy, Fort Worth, TX

Kortnee Roberson, MD - Department of Family Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL

Jessica De Leon, PhD - Department of Family Medicine and Rural Health, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL

Warren Ferguson, MD - Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA

George W. Saba, PhD - Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine

Corresponding Author

Jennifer Edgoose, MD, MPH

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.