The United States faces an increasing shortage of primary care physicians, which community-based medical schools aim to overcome by increasing the primary care physician supply.1 The timely study by Deutchman and colleagues reveals the extent to which training of primary care physicians at allopathic medical schools may be overestimated,2 reporting that only 22% of graduates from a sample of 14 medical schools entered primary care practice. While this study was not designed to statistically compare the output of primary care physicians among schools or regions, the number of graduates entering primary care fields is frequently compared between schools to analyze their relative contribution to the primary care workforce.3 Such relative comparisons and rankings are useful for identifying schools that emphasize primary care training, but absolute benchmarks are needed for schools to know how many primary care physicians they must train to overcome the increasing shortage.

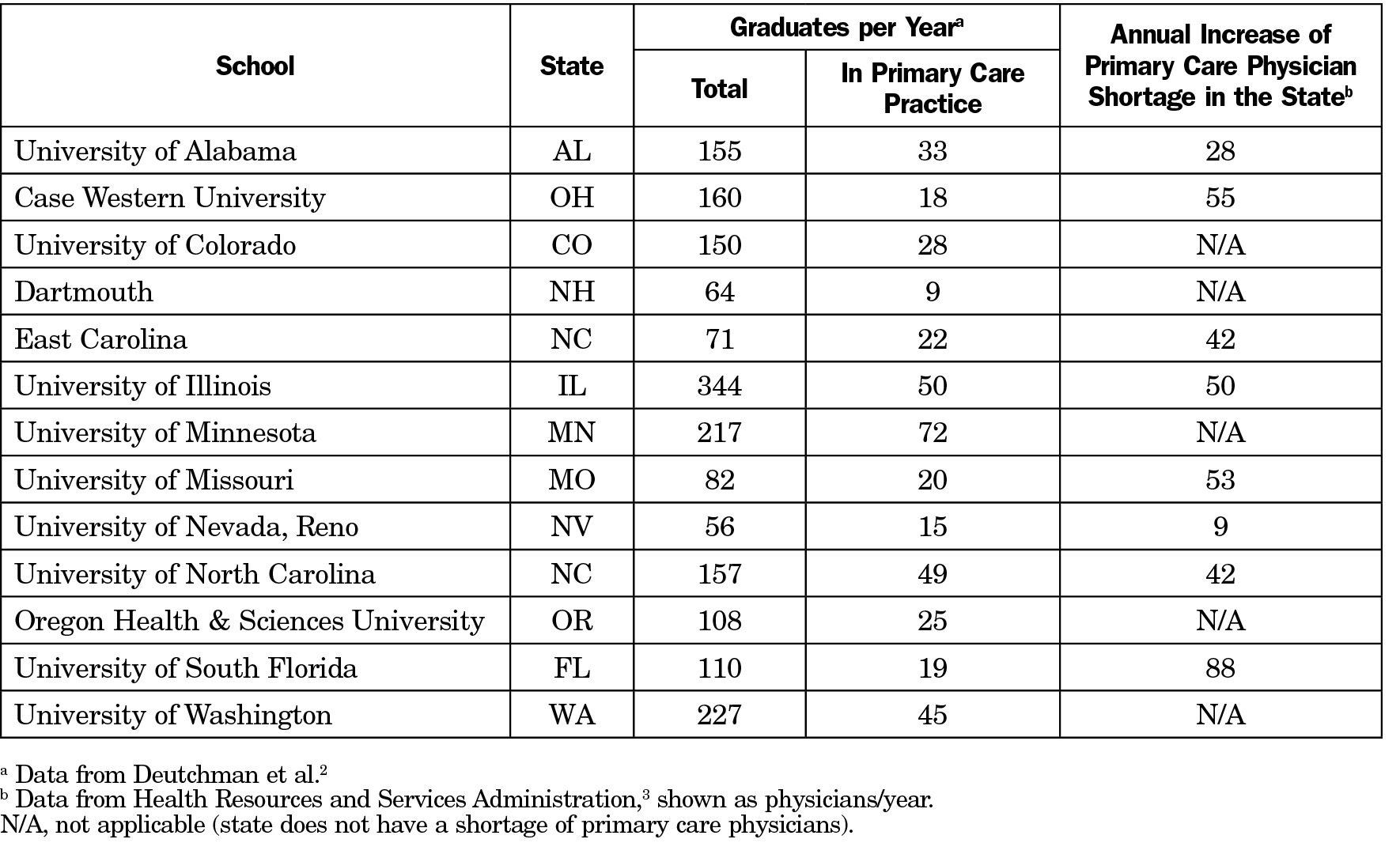

By 2023, the projected shortage of primary care physicians is between 21,400 and 55,200 nationally.4 However, this shortage varies significantly by state and is increasing much faster in some states than others.5 Based on the Health Resources and Services Administration’s projections spanning 2013-2025,5 we calculated the annualized increase in the primary care physician shortage for states represented in Deutchman et al’s study. We then compared it to the annualized number of primary care physicians produced by each school (Table 1). Eight of 13 schools identified by name were located in states where the primary care physician shortage was increasing at a rate of 9-88 physicians/year. By comparison, each of these eight schools graduated 15-50 physicians per year who would go on to practice primary care. As an example of the gap between school-specific primary care physician training and the statewide rate of change in the physician shortage, the Brody School of Medicine (BSOM) at East Carolina University graduated an average of 71 physicians/year of whom 22 entered primary care practice, while the shortage of primary care physicians in North Carolina (where BSOM is one of four allopathic medical schools) grew by 42 per year.

For schools such as BSOM that have a mission to increase the supply of primary care physicians in their state,1 this comparison between alumni entering primary care and absolute benchmarks of primary care physician shortage reveals how far we must go to meet the demand for primary care physicians. Even if all BSOM graduates entered primary care, it would not be sufficient to close the gap in the state. With other states facing similar challenges, multiple approaches may be required to meet the demand in states and regions where the primary care physician shortage is greatest. Approaches include incorporating community recommendations in the admissions process, increasing enrollment at primary care-focused schools, focusing on underrepresented student populations, or increasing production of primary care physicians at large research-oriented schools. Medical education leaders, health care professionals, and policy makers should look at statewide and regional strategies to increase numbers of primary care physicians, building upon the localized successes of individual schools.

There are no comments for this article.