Background and Objectives: Training residents in family-centered approaches offers an opportunity to investigate how learners translate skills to real clinical encounters. Previous evaluations of a family systems curriculum have relied on self-assessment and narrative reflection to assess resident learning. Assessment of learning using encounter observation and objective tools, including evaluation of empathy, allows for a deeper understanding of how residents transform curricular education into clinical practice.

Methods: We evaluated resident learning from a longitudinal family systems curriculum delivered during the third year of a four-year residency training program. Using the Family-Centered Observation Form (FCOF), we analyzed seven pre- and postcurriculum videotaped encounters for changes in family-centered interviewing skills. We assessed changes in empathy before and after the curriculum using the Jefferson Empathy Scale.

Results: There was a trend toward improvement in all family-centered skills, as measured by the FCOF, though the improvements were only statistically significant in the area of rapport building. Statistically significant improvement in empathy occurred for all participants. Narrative reflection demonstrated that residents found the curriculum valuable in ways that we were unable to objectively measure.

Conclusions: Training in family systems can enhance patient interactions and may improve empathy. Evaluation of family-centered skills is challenging and takes a significant amount of time and planning. The FCOF can help learners identify how to use family-centered concepts and skills in a typical family medicine outpatient visit. Further study is needed to determine whether patients seen by doctors who use family-oriented skills have better experiences or outcomes.

Training in family systems and family-oriented care can prepare physicians to care for individuals and families in the context of their social and emotional environment, while allowing physicians to learn how their own family of origin may affect clinical interactions and decision-making.1,2 A national survey of family medicine residency programs found a majority of program directors and chief residents valued family systems training, despite reports that these topics were not consistently incorporated into behavioral science teaching.3 A 2017 retrospective survey found that only about 25% of family medicine residents on behavioral science rotations reported working with couples, families, or learning effective counseling techniques with these populations.4 Clinical experience and research also show that empathy (the ability to understand the feelings of the patients and communicate that understanding back to them) facilitates better care.5,6

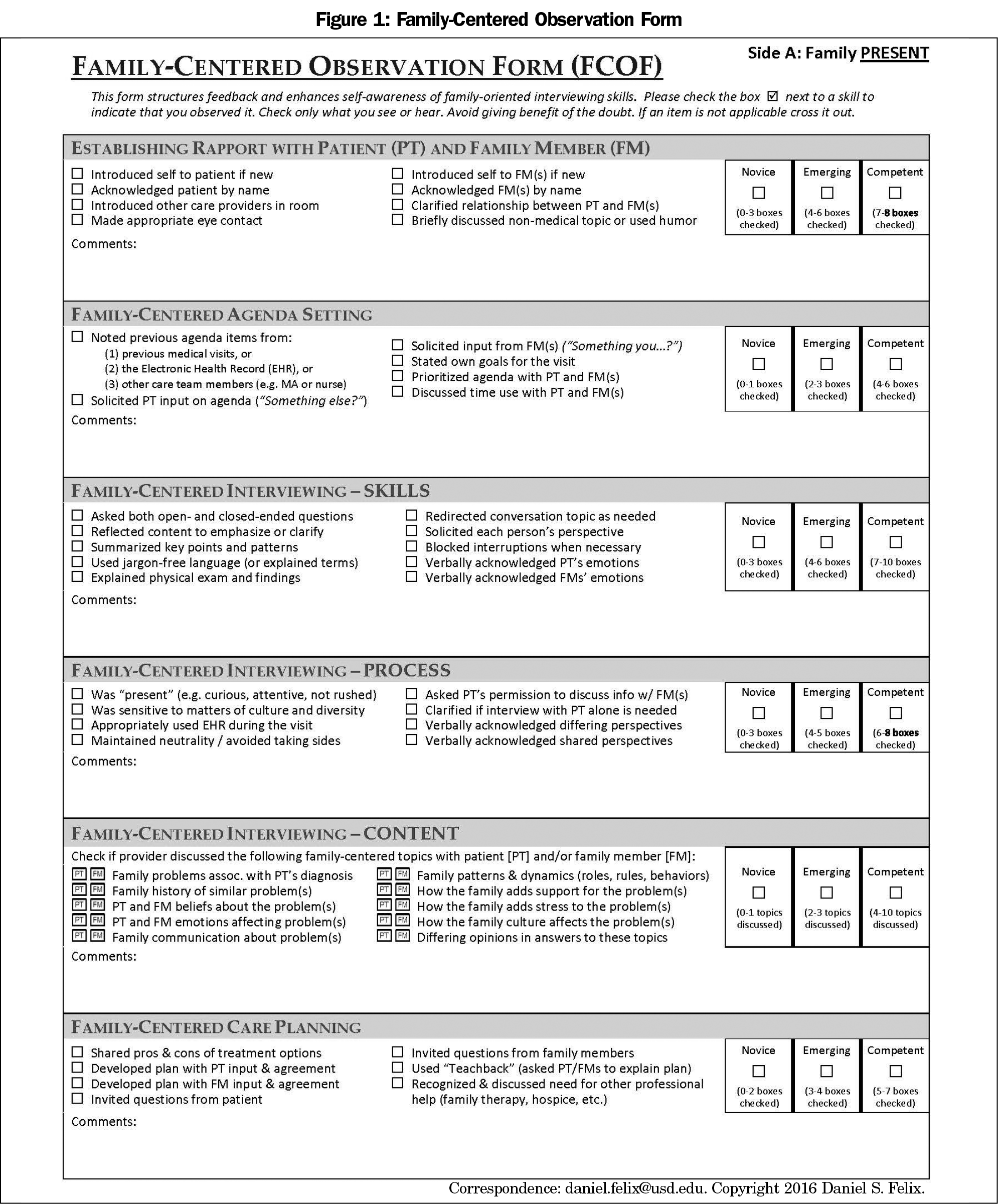

Our curriculum introduced residents to family systems concepts, provided them with opportunities to assess their family of origin, and learn family-oriented skills in clinical practice.7 Doherty and Baird’s development levels for family-centered care provided a general framework for our learners.8 For this study, we incorporated the Family-Centered Observation Form (FCOF, Figure 1), an evaluation tool that includes specific family-oriented skills that can be used with individuals and families. We administered the Jefferson Empathy Scale, Health Professionals Version (JES) and the FCOF before and after completing the curriculum. Specifically, we wanted to evaluate whether residents’ use of family-oriented clinical skills changed after the curriculum and assess whether the curriculum affected their reported feelings of empathy.

Fourteen postgraduate year-3 residents participated in a biweekly family systems curriculum over 6 months. Seven matched pre- and postencounters using the FCOF, and nine pre- and post-JES were completed. Inpatient and away clinical rotations, parental leave, and resident difficulty obtaining appropriate pre- and postcurriculum encounters precluded our ability to include the entire cohort. Prior to starting the curriculum, residents recorded an encounter with a volunteer patient with a chronic condition for whom they were the primary care physician. Two behavioral science faculty who taught the course separately coded the videos using the FCOF.9 At the training’s conclusion, residents recorded a separate encounter with a different patient that was also coded using the FCOF. A Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare the pre- and postencounters. Additionally, each resident completed a pre- and postempathy rating using the JES, Health Professionals version, and these pre- and postscores were compared using a paired t test. We also asked the residents to respond to open-ended questions about the curriculum’s impact on their practice. The Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board determined this study to be exempt.

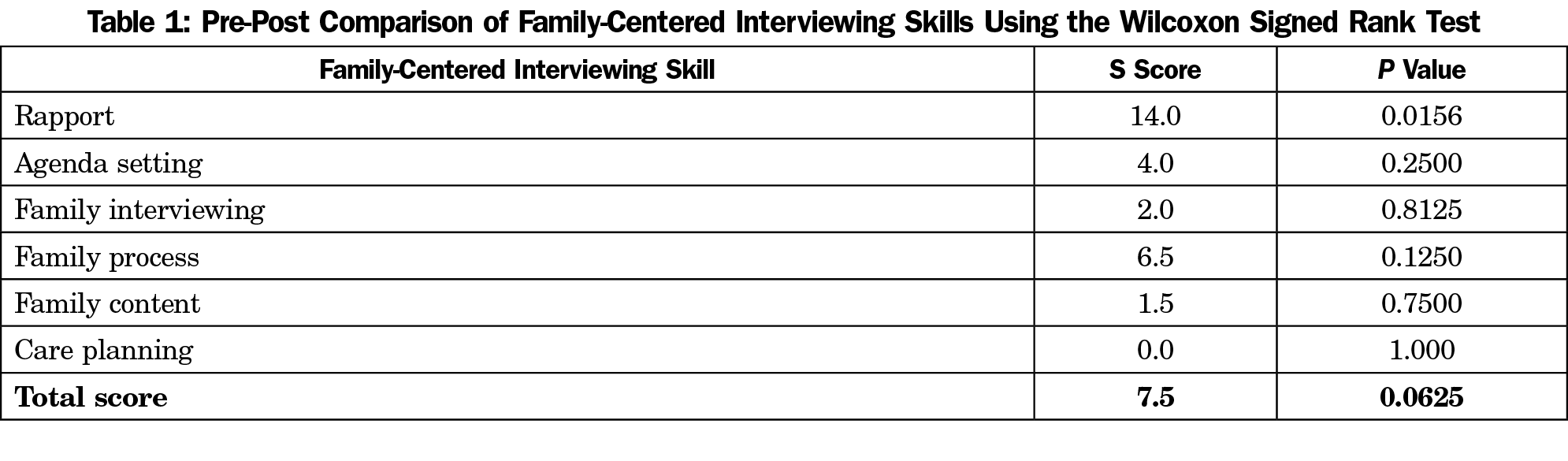

We compared seven pre- and postencounters using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test to assess improvement in using family-centered care skills, as defined by the FCOF, during a clinical encounter. An average of 10 months passed between pre- and postencounters. The interrater reliability of the FCOF was 90% and was presented in an initial poster presentation for the same cohort.10 Of the six family-centered domains, rapport was the only skill that demonstrated significant difference between pre- and postencounters (S score=14.0, P<.02, Table 1). We performed a paired t test on the pre- and post-JES Health Professional scores. The mean and standard deviation for the pre- and postscores were 110.2 (8.0) and 112.9 (8.2), respectively. Nine participants’ empathy scores improved, and the change was statistically significant (t[8]=5.66, P<.001).

Qualitative Data

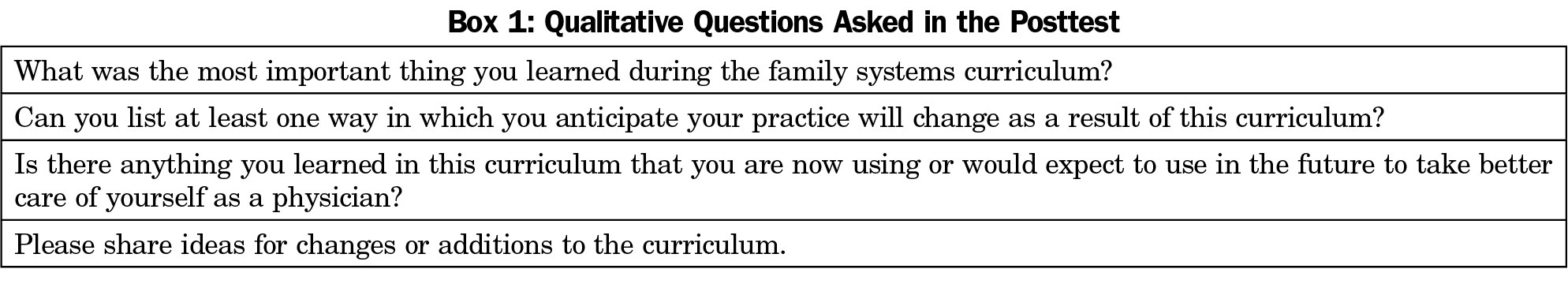

At the curriculum’s conclusion, we asked residents to respond to reflection questions (Box 1). All residents indicated that they valued the curriculum and had changed their practice based on their learning. Responses focused on gathering more information about a patient’s family background, especially when the patient is complex or has multiple medical issues. One resident reflected on the use of family systems in their clinical care:

Consideration of the social-family context has become a more important part of my approach to patients. When encountering a challenging clinical problem, I am more likely to delve into family background or ask about psychosocial stressors.

Another resident stated that

[the curriculum helped me come to the] realization that I bury a lot of my own emotions in order to be able to take on others’ which isn’t always healthy.

One resident recognized connections between their complicated family dynamics and their relationships with patients:

I realized my own complicated upbringing likely leads me to become overinvolved with certain patients, spending more time during visits and investing more mental/emotional energy out of an identification with their experiences, conscious or not.

The family systems curriculum yielded improvement in the development of rapport and empathy as measured by the FCOF and JES. Qualitative results suggested residents experienced increased ability to self-reflect, improved self-awareness and enhanced understanding of the importance of family context in medical care.

Assessment of postclinical encounters demonstrated a trend toward improvement in skills; however, encounters’ variability precluded meaningful comparisons with precurriculum encounters. Although we don’t know if these observed skills or changes in practice affected patients’ perception of care or influenced clinical outcomes, previous research indicates that a physician’s level of empathy does improve patient outcomes.11 Residents noted that reflecting upon their family of origin benefited their well-being. This supports the idea that insight into one’s own personal history may provide protection from guilt, overresponsibility for the patient’s current health challenges, and reactivity. Increased self-awareness may provide some protection from burnout by allowing the physician to suspend unrealistic expectations of themselves in the care of complex cases. Although the JES improvement was statistically significant, a 2.7-point difference in mean scores may not be considered a clinically significant change. In order to determine any meaningful clinical significance, future studies could consider gathering feedback from patients before and after the curriculum is delivered and assess the patient’s perception of changes in empathy.

The study had certain limitations. First, our sample size was small and specific to one institution. Results may not be generalizable to other settings, nor is it possible to draw conclusions about clinical significance in such a small group. Second, we could not discern whether the increase in empathy was associated with the additional time in training or other aspects of residency education during the fourth year. Third, using a required curriculum meant we were unable to have a control group that did not receive the intervention. Finally, we were not blind to the sequence of recording, nor were we able to control for any bias toward specific participants.

There is the general lack of consensus among core faculty about what family-oriented care is and how one should provide it. Research demonstrates various benefits to the practice of family-oriented care, including enhanced communication with families,12 increased confidence in leading family meetings,13 and deepening the helping relationship with families.14 Future research should investigate how to effectively build faculty’s family-oriented precepting skills to assist residents in consistently using these skills during their clinical encounters.

References

- Doherty WJ, Baird MA. Family therapy and family medicine: toward the primary care of families. New York: Guilford Press; 1983.

- Mengel MB. Physician ineffectiveness due to family-of-origin issues. Fam Syst Med. 1987;5(2):176-190. doi:10.1037/h0089711

- Korin EC, Odom AJ, Newman NK, Fletcher J, Lechuga C, McKee MD. Teaching family in family medicine residency programs: results of a national survey. Fam Med. 2014;46(3):209-214.

- Zubatsky M, Brieler J, Jacobs C. Training experiences of family medicine residents on behavioral health rotations. Fam Med. 2017;49(8):635-639.

- Rakel DP, Hoeft TJ, Barrett BP, Chewning BA, Craig BM, Niu M. Practitioner empathy and the duration of the common cold. Fam Med. 2009;41(7):494-501.

- Hojat M, Louis DZ, Maxwell K, Markham FW, Wender RC, Gonnella JS. A brief instrument to measure patients’ overall satisfaction with primary care physicians. Fam Med. 2011;43(6):412-417.

- Schiefer R, Devlaeminck AV, Hofkamp H, Levy S, Sanchez D, Muench J. Brief report: A family systems curriculum: back to the future? Fam Med. 2017;49(7):558-562.

- Doherty WJ, Baird MA. Family Therapy and Family Medicine: Toward the Primary Care of Families. New York: Guilford Press; 1983.

- Felix D, Mauksch L. Improving family interviewing skills using the family centered observation form: an online training module for healthcare providers. http://www.fcof.us. Published 2017. Accessed July 21, 2020.

- Schiefer R, Levy S. A family systems curriculum for third-year residents: building empathy and family centered skills. Poster Presentation. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference. Washington, DC; May 5-6, 2018.

- Yugero O, Marsal JR, Esquerda M, Soler-Gonzalez J. Occupational burnout and empathy influence blood pressure control in primary care physicians. BMC Fam Pract 2017; 12: 18(1): 63. doi:10.1186/s12875-017-0634-0

- Delacruz N, Reed S, Splinter A, et al. Take the HEAT: A pilot study on improving communication with angry families. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(6):1235-1239. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2016.12.012

- Butler DJ, Holloway RL, Gottlieb M. Predicting resident confidence to lead family meetings. Fam Med. 1998;30(5):356-361.

- Larivaara P, Väisänen E, Väisänen L, Kiuttu J. Training general practitioners in family systems medicine. Nord J Psychiatry. 1995;49(3):191-197. doi:10.3109/08039489509011905

There are no comments for this article.