As we embark on the next iteration of our Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) specialty requirements, striking a balance between standardization and innovation is key for the future of family medicine and how we, as program directors, prepare our residents to serve our communities. The national data we collect through the Milestones assessment of residents will be essential in charting that path.

With the introduction of the ACGME Outcomes Project in 2001, we began to focus the assessment of residents and residency curriculum on six established, standard competencies. These initial efforts to move away from proxy measures of competency such as time-based curriculum, numbers of procedures, and counting patient encounters were difficult, especially in family medicine. The changes in assessment required us to identify opportunities for multisource feedback. These tools include direct observation, quality and safety data, incorporation of patient experience, and traditional examinations. All of these required an appreciation of the differences in individual learner trajectory toward graduation and board certification. With many family medicine programs based in community settings we are often faced with limited academic infrastructure, faculty development support, and scant protected time for thoughtful interaction with learners. Collectively, we sought a framework with greater specificity to guide our assessments.

In 2014, the Family Medicine Milestones 1.0 were introduced.1 This tool was designed by an expert panel of family medicine educators with major input from the ACGME Family Medicine Review Committee and the American Board of Family Medicine. At the outset, program directors adopted this tool as a mechanism to improve residency program curriculum as reflected by the performance of individual residents over the course of their training. The Milestones were also designed to facilitate resident professional development through both curriculum and formative assessment.

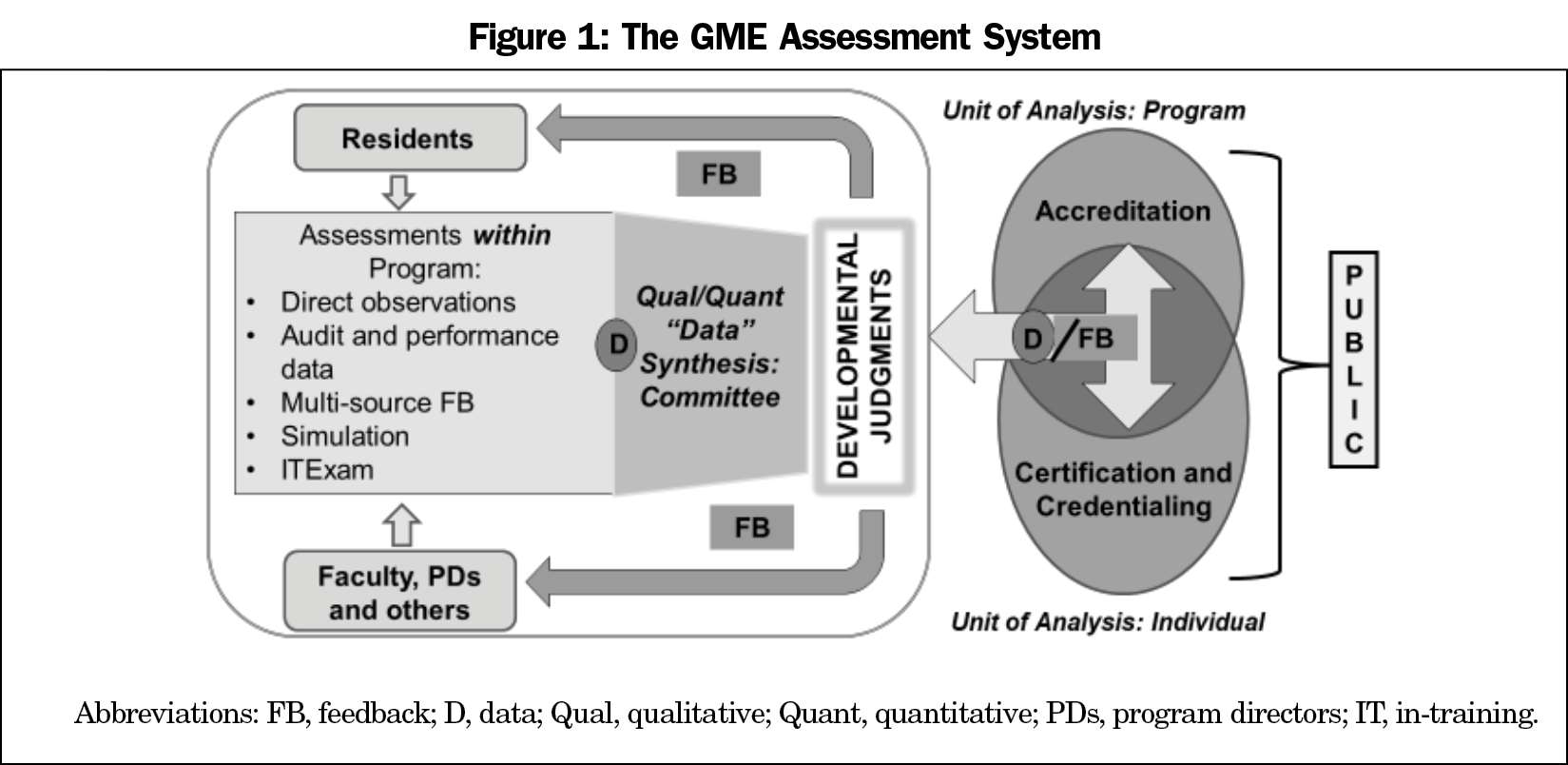

With the introduction of the Next Accreditation System, the Clinical Competency Committee (CCC), and the 2015 ACGME Requirements for Family Medicine, the call for renewed focus on competency-based medical education shifted our use of Milestones data from primarily program assessment to also include individual resident assessment as a product of the curriculum. As depicted in Figure 1, multisource feedback and input from the CCC results in continuous improvement for both individual residents and the program measured against an objective set of standards.

Recognizing that the consequences of an assessment affect how an assessment is used, the Milestones were deliberately intended to be low stakes. As a formative assessment of the individual program, family medicine program directors took their responsibility seriously, avoiding halo assessment, leniency error, and straight-line assessments of residents as evidenced by early national trends in family medicine reporting to the ACGME.2 For our specialty, this is a cause for celebration. We recognize that milestones do not measure the latent ability of the individual residents and appropriately use the full range of developmental scale options.3

Milestones are recorded by all program directors on every resident, representing an unprecedented opportunity to examine our national system of graduate medical education and its outcomes in a longitudinal way. Aggregate Milestones 1.0 data from 2017-2019, the first full cohort of residency graduates, demonstrates that family medicine program directors report the full range of performance on each of the 22 milestones, underscoring our thoughtful reporting and the usefulness of the data. Granted, the system is evolving, but it has improved our ability to look at competencies beyond medical knowledge and patient care in a deliberate manner. The data collected represent a unique, national resource and are available online at https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Milestones/Resources.

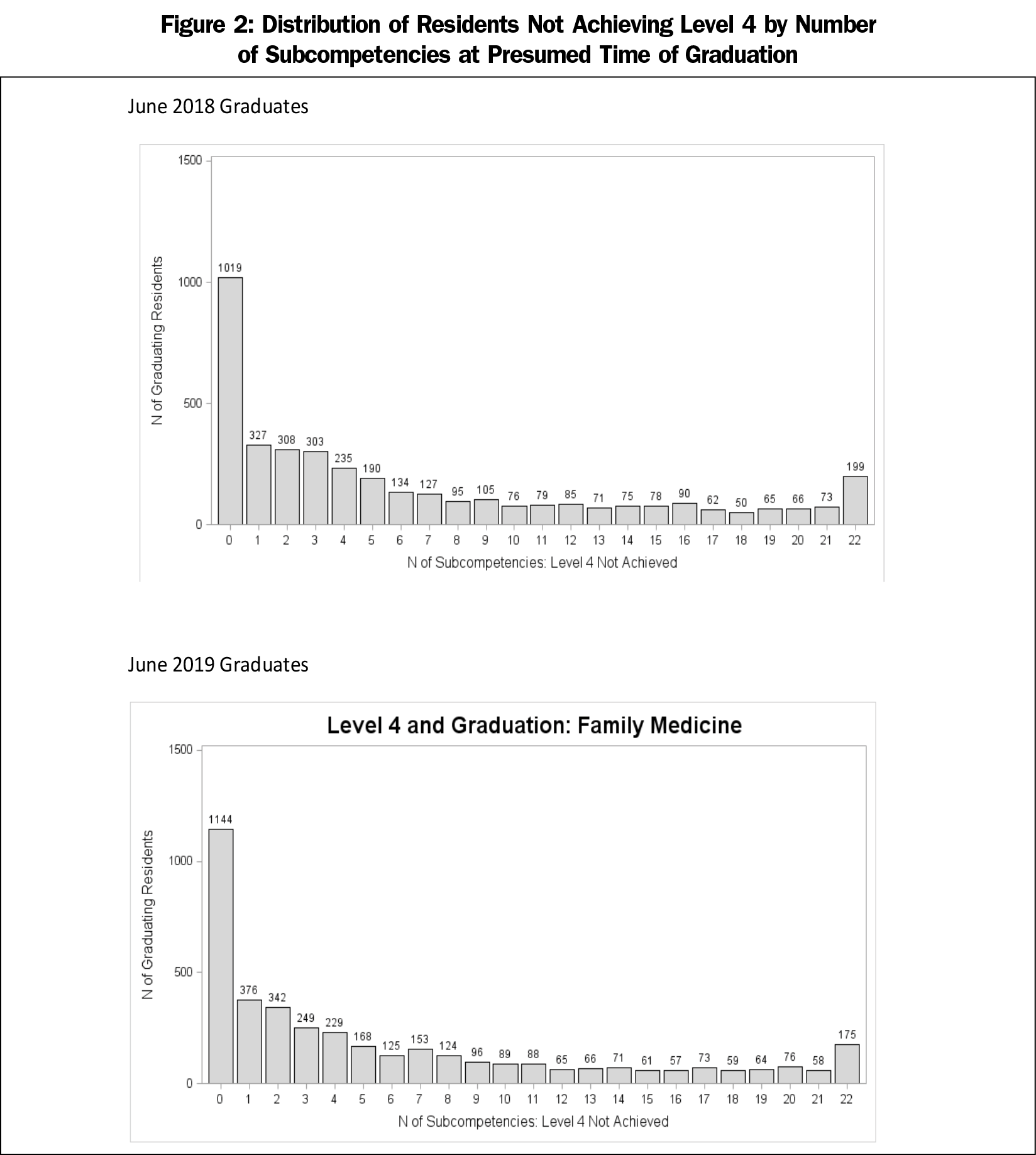

So what have we learned? In 2019, of the 4,008 PGY-3 family medicine residents, 1,144 (28.5%) achieved a level 4 in all 22 of the Milestones. This level represents the recommended graduation target as roughly correlated with proficiency in the Dreyfus model and readiness for unsupervised practice. At the other end of the spectrum, 175 (4.3%) of the PGY-3 residents in 2019 did not reach a level 4 on any of the 22 milestones, and approximately 20% did not reach level 4 on half or more of the 22 milestones (Figure 2). Nationally, we reported a below-mean rating on SBP-1 “Provides Cost-Conscious Medical Care,” SBP-3 “Advocates for Individual and Community Health,” and PBLI-3 “Improves Systems in Which the Physician Provides Care,” all of which are fundamental components of family medicine.4

What does this mean? Did these residents train in programs that were simply more stringent in their ratings? Did programs struggle with curriculum and effective assessments in key Milestones, especially in the domains of system-based practice and practice-based learning? What happened to these graduates once they entered practice? As the discipline begins to implement Milestones 2.0, family medicine has an opportunity to explore these questions, and more importantly, the outcomes of its graduates from 2017 to 2019.

During the recent pandemic, we have experienced upheaval of our planned educational experiences and traditional assessment tools. We have also acknowledged the implicit and explicit biases in our society and are wrestling with changes to our systems that have been deferred for far too long. For at least the next few years, program directors will be unable to rely on our traditional metrics for ascertaining resident competence to practice independently. We have reached a critical juncture in needing reliable ways to define minimum expectations based on competency, not scheduled rotations or numbers of procedures. The importance of competency-based medical education and processes for meaningful assessment have been accelerated. Whether the Milestones data have meaning and validity is unclear, but we must avoid the tendency to disregard imperfect data.

If we assume that Milestones measure essential expectations of family medicine residency training and that they are reported accurately, we must answer some critical questions. We cannot be willing to accept that nearly 72% of our graduates are leaving our programs with at least one subcompetency below that recommended for unsupervised practice. Even more critical is that we continue to graduate family physicians who meet none of the recommended subcompetencies. Establishing an acceptable floor for individual residents is essential to program standardization. Do these findings reflect the competency of individual residents or the adequacy of our training programs? Family medicine has been expanding at one of the most rapid rates in our history and of all medical specialties to meet the nation’s primary care needs. We must ensure that our expansion has not been too fast to ensure competence of our graduates. Assurance of competence should accompany any latitude to innovate.

Milestones 2.0 arose as an expansion of the original process, including a call for volunteers, adding resident members and a public member. The new version revisited appropriate standards of performance and includes a detailed supplemental guide. The tool then underwent substantial public comment before implementation in July 2020. These revised measures may more accurately reflect our expectations of our curriculum and, as a result, will improve resident attainment of recommended competencies. Our individual CCCs and Program Evaluation Committees should use these data to revise our curriculum through an iterative, continuous improvement process to ensure that each resident has an opportunity to reach their potential. We must be willing to hold programs accountable to our shared standards. Finally, we must continue to advocate for adequate protected faculty time and development to allow for thoughtful assessment of residents and evaluation and improvement of our programs. Our ability to innovate hinges on our assurance that residents meet a minimum standard of performance.

To fulfill our commitment to society to deliver what we say a family physician is and can do, we must continue to study the data we are collecting and leverage our findings to individually and collectively improve family medicine residency education.

There are no comments for this article.