Family medicine residency programs are tasked with training physicians capable of, as the Millis Commission put it in 1966, “highly competent provision of comprehensive and continuing medical services.”1 However, due to ever-increasing complexity of care and reductions in training time, the ability of programs to deliver on this task is increasingly stressed. The optimal length of training has been debated since the specialty’s inception, with recognition of the need for curricular flexibility and that training could take up to 4 years to complete.2

In 2004 the Future of Family Medicine report called for residency innovation.3 Beginning in 2006 the P4 Project facilitated 14 programs modeling diverse changes in curriculum design and training length.4 Middlesex Health implemented the first required 4-year curriculum in 2007.5 Several optional 4-year models were also developed. In 2012 the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Length of Training Pilot, a prospective case-control study of the 4-year residency, was initiated and is currently reporting findings.6

What Is a 4-Year Residency?

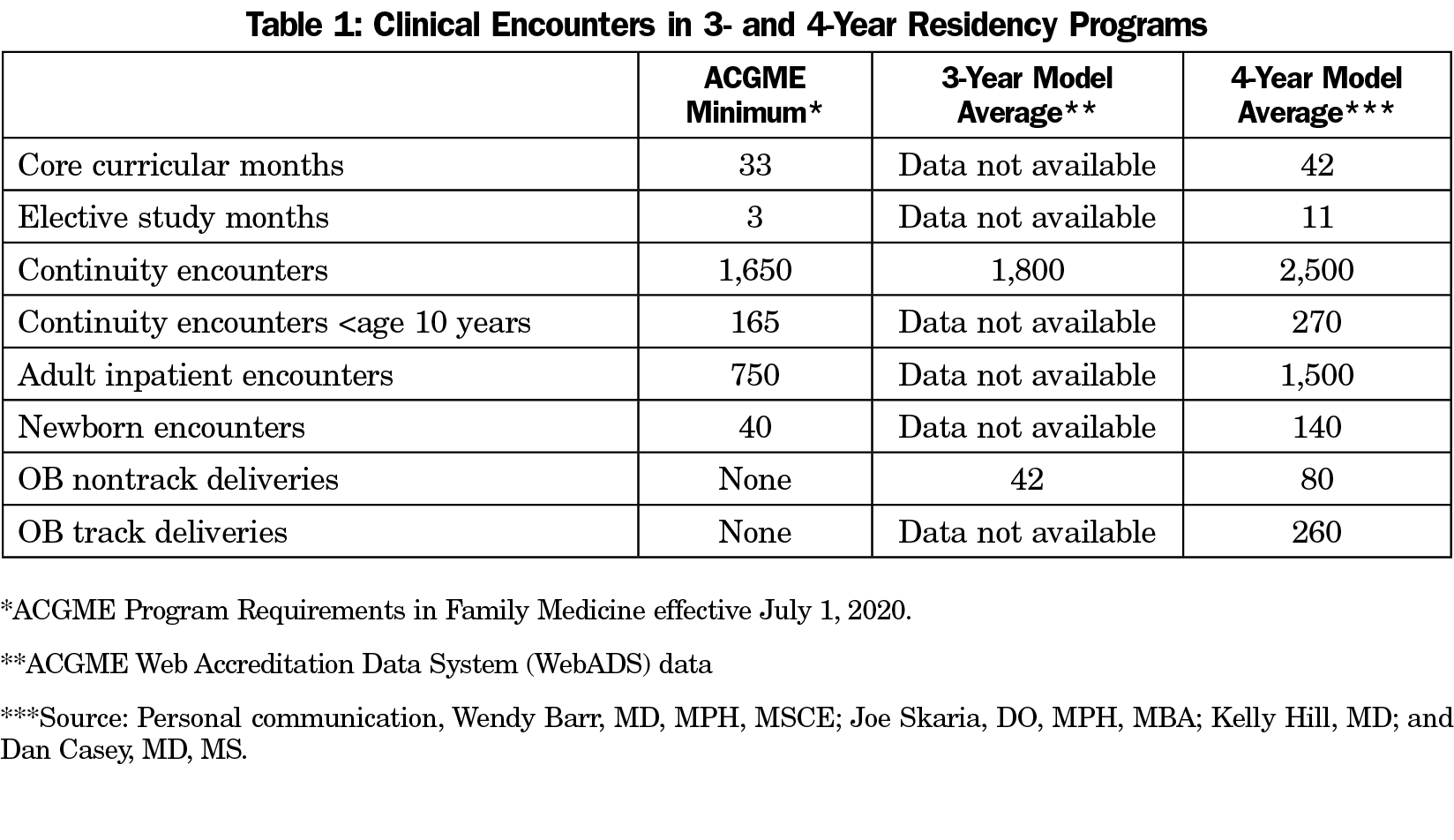

A 4-year residency is a substantially enhanced training experience.7 It contains all the core components of a 3-year program with three significant additions. First is an enhanced core curriculum with 6 additional months of required experiences in areas of particular need such as care of children, practice and health system management, and population health. Second is an area of individual concentration (AOC) consisting of 6 months of immersion in a specific area of passion or anticipated practice need such as maternal-child health, academics, or behavioral health. Finally, residents receive enhanced continuity experience with up to 50% additional clinical encounters in all areas of family medicine (Table 1).This basic model can be implemented in a variety of approaches and settings based on program focus and community need.

There Is More to Teach

The fundamental structure of family medicine training has not changed since 1968. However, to meet escalating societal needs family physicians must now have substantially more expertise. Complexity of care is increasing, and diagnostic and therapeutic modalities are proliferating. Today’s family physicians must be competent in many areas not envisioned 50 years ago, including health information management, population health, HIV care, point-of-care ultrasound, management of teams within complex health systems, telemedicine, genomics, medication-assisted treatment of addiction, leadership, and advocacy.

Training Time is Decreasing

The 2003 implementation of ACGME duty hours led to a substantial reduction in training time. While an important advance, the 2020 American Board of Family Medicine family leave guidelines remove up to an additional 8 weeks of training. Any serious future efforts to promote trainee wellness will reduce training even further.

Programs are increasingly struggling to fit even basic requirements into 3 years, with continuity visits declining. Both residents and program directors feel medical school graduates are not adequately prepared for residency,8,9 a trend exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Residents are less confident in their preparation to enter practice, with 17% planning a fellowship and another 20% considering it.10

Some argue that wide implementation of competency-based education could deliver more efficient training and create needed curricular space within the existing 3-year model. However, there is no substitute for substantial experience in developing competence and confidence. Reducing it will only exacerbate current trends.

Scope of Practice Is Eroding

Broad scope is a defining characteristic of family medicine, and a key student attraction to the discipline. However, care of children, maternity care, and procedures are all declining as need is increasing, particularly in rural and other low-resource areas. Broader scope is associated with higher levels of medical knowledge,11 lower levels of burnout,12 higher levels of job satisfaction,13 and lower costs of care.14 If scope continues to narrow it will be increasingly difficult to distinguish ourselves, at least in the eyes of some, from the large numbers of physician assistants and nurse practitioners entering the primary care workforce.

Residents Want Choice

Additional individualized training to achieve broader scope is difficult to achieve in the increasingly constrained 3-year model. Robust AOCs are in effect structured longitudinal fellowships integrated in parallel with ongoing generalist training. They are educationally ideal for physicians planning generalist practice, and much more than an aggregation of a few months of electives. They can also provide advanced degrees. Completion of an AOC is associated with broader scope of practice,15 while stand-alone fellowships are associated with more focused scope. Production of family physicians with additional expertise is particularly important in maternity care and academics, both critical to our discipline’s future.

We Must Preserve the Ability to Innovate

If family medicine is to maintain its position as the lead primary care specialty we must preserve the ability to innovate in response to new challenges, and train future leaders in health care transformation. However, lack of available training time stifles any opportunity for widespread curricular innovation. Further, many residency offices have fallen behind industry best practices and are no longer aspirational innovative spaces.

Both Students and Programs Are Interested

Family medicine has the broadest scope yet the shortest duration of training of any US specialty, and other than Canada, the shortest in the developed world. Many students are skeptical they can acquire breadth and feel both competent and confident in less time than narrower specialties. Family medicine must appear attractive if we are to match more than 8% of US medical graduates.

At least one-third of students view 4-year curricula positively.16 Forty-eight percent of Family medicine residents expressed interest in a fourth year of training if it were available.17 Applicant pool and match performance are unaffected by extended duration of training.18 Required 4-year programs report dramatic growth in both volume and quality of applications, with a 62% increase in US applicants per offered position between 2014 and 2020 (Personal communication, Wendy Barr, MD, MPH, MSCE).

There is also substantial interest among programs. Twenty-five percent of faculty feel the optimal duration of required training should be 4 years19; 34% of current 3-year directors would consider converting their program to 4 years if financial barriers were removed, while 16% would convert regardless if permitted by the ACGME (CERA Survey data, personal communication, Wendy Barr, MD, MPH, MSCE).

Four Years Is Financially Feasible

From a program perspective, adding a fourth year requires resident salary support plus variable amounts of additional faculty and operational expenses. Additional revenue can come from a variety of sources. Fourth-year resident professional fees typically cover resident direct expenses. If under cap, a fourth year of training in family medicine receives only 50% of federal direct medical education funding, but more lucrative indirect medical education support remains intact. Teaching health center funding, health system partnerships, and institutional support are all available sources of additional revenue. All required 4-year programs have demonstrated sustainable funding in a variety of models, maintaining or improving their contribution margins to their sponsoring institutions.20

From a resident perspective there is an intrinsic economic trade-off between a fourth year of resident salary ($75,000) and an additional year of practice income ($215,000). Choosing a fourth year therefore appears to carry an opportunity cost of $140,000. However, once marginal tax brackets are accounted for, the increment shrinks to $93,000. Four-year graduates possess unique attributes that are highly valued by employers and provide the opportunity to quickly defray this increment. Additional clinical experience and broader scope facilitate higher levels of early practice productivity. Four-year graduates are also prepared to assume more highly compensated leadership roles earlier in their careers.

Family medicine is the specialty with the broadest scope but shortest training time. Training is currently being eroded from both ends with more to learn and less time to learn it. Scope of practice is diminishing and threatening our identity and differentiation from other primary care clinicians. These constraints are limiting our ability to be innovators and primary care leaders. Students want to graduate competent and confident, but are increasingly skeptical that they can acquire either in the current model. Four years of training is not a deterrent to entering family medicine, but 3 years may soon be. As we consider the future of training over the next decade, now is the time to bolster training, not reduce it.

The 4-year residency provides a flexible solution to all these challenges. It is both practically and financially feasible, and sought by increasing numbers of applicants and programs. It would be a serious mistake for our discipline to eliminate this option. To do so would commit family medicine to an increasingly confining curricular box and continued decline in scope of practice.

The family medicine community should advocate to the ACGME to preserve the opportunity for interested programs to continue in or transition to a 4-year model in response to their training goals and community needs. This would provide the discipline with needed flexibility to address current curricular constraints, maintain broad scope of practice, and innovate in response to future challenges.

References

- Millis Commission. The graduate education of physicians: the Report of the Citizens Commission on Graduate Medical Education. Chicago: American Medical Association; 1966.

- Carek PJ, Anim T, Conry C, et al. Residency training in family medicine: a history of innovation and program support. Fam Med. 2017;49(4):275-281.

- Bucholtz JR, Matheny SC, Pugno PA, David A, Bliss EB, Korin EC. Task Force Report 2. Report of the Task Force on Medical Education. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 1):s51-s64. doi:10.1370/afm.135

- Carney PA, Eiff MP, Waller E, Jones SM, Green LA. Redesigning residency training: summary findings from the Preparing the Personal Physician for Practice (P4) project. Fam Med. 2018;50(7):503-517. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.829131

- Douglass AB, Rosener SE, Stehney MA. Implementation and preliminary outcomes of the nation’s first comprehensive 4-year residency in family medicine. Fam Med. 2011;43(7):510-513.

- Carek PJ. The length of training pilot: does anyone really know what time it takes? Fam Med. 2013;45(3):171-172.

- Pugno PA. One giant leap for family medicine: preparing the 21st-century physician to practice patient-centered, high-performance family medicine. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(suppl 1):S23-S27. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2010.S1.090291

- Engelhardt KE, Bilimoria KY, Johnson JK, et al. A national mixed-methods evaluation of preparedness for general surgery residency and the association with resident burnout. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(9):851-859. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2020.2420

- Lyss-Lerman P, Teherani A, Aagaard E, Loeser H, Cooke M, Harper GM. What training is needed in the fourth year of medical school? Views of residency program directors. Acad Med. 2009;84(7):823-829. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a82426

- Sairenji T, Dai M, Eden AR, Peterson LE, Mainous AG III. Fellowship or further training for family medicine residents? Fam Med. 2017;49(8):618-621.

- Peterson LE, Blackburn B, Peabody M, O’Neill TR. Family physicians’ scope of practice and American Board of Family Medicine recertification examination performance. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(2):265-270. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2015.02.140202

- Weidner AKH, Phillips RL Jr, Fang B, Peterson LE. Burnout and scope of practice in new family physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):200-205. doi:10.1370/afm.2221

- Rivet C, Ryan B, Stewart M. Hands on: is there an association between doing procedures and job satisfaction? Can Family Physician. 2007;53(1):93, :e.1–5, 2.

- Bazemore A, Petterson S, Peterson LE, Phillips RL Jr. More comprehensive care among family physicians is associated with lower costs and fewer hospitalizations. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(3):206-213. doi:10.1370/afm.1787

- Eiff MP, Hollander-Rodriguez J, Skariah J, et al. Scope of practice among recent family medicine residency graduates. Fam Med. 2017;49(8):607-617.

- Duane M, Dovey SM, Klein LS, Green LA. Follow-up on family practice residents’ perspectives on length and content of training. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17(5):377-383. doi:10.3122/jabfm.17.5.377

- Carney PA, Eiff MP, Waller E, Peterson LE. Factors associated with interest in pursuing a fourth year of family medicine residency training. Fam Med. 2017;49(5):339-345.

- Eiff MP, Ericson A, Uchison EW, et al. A comparison of residency applications and match performance in 3-year vs 4-year family medicine training programs. Fam Med. 2019;51(8):641-648. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.558529

- Starfield Summit IV: Re-envisioning Family Medicine Residency Education. https://residency.starfieldsummit.com/community-dialogue. Accessed March 27, 2021.

- Douglass AB, Barr WB, Skariah JM, et al. Financing the fourth year: experiences of required 4-year family medicine residency programs. Fam Med. 2021;53(3):195-199. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.249809