Diversity, equity, and inclusion are core values in medical education; however, the concepts as currently incorporated into educational models and requirements are limited, just scratching the surface of the actual need and aim. Fostering diversity recognizes and values individual and group differences such as race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, education, age, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, disability status, religion, location, language, country of origin, familial status, and other personal experiences. Inclusion builds upon diversity by ensuring a culture of belonging, respect, value, and engagement for all. The lens of diversity requires inward reflection on who we are as a care team of residents, faculty, and clinical staff, as well as outward analysis and perspective on who, how, and what care we provide. From this viewpoint, we consider our alignment in our communities and embrace our differences in the role of achieving health equity—the highest level of health for all people. Inclusive excellence provides an active, substantive context in which diversity, equity, and inclusion integrates into institutional and programmatic mission, culture, operations, education, engagement, and quality improvement activities.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Family Medicine Requirements state sponsoring institutions (SIs) and programs must implement policies, procedures, and practices focused on systematic recruitment and retention of a diverse and inclusive workforce of residents, fellows, faculty, and staff; ensure residents demonstrate competency in respect, responsiveness, and communication with diverse patient populations; and provide structured curriculum that addresses the social determinants of health (SDH) and health care disparities.1 At an institutional level, the ACGME Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) furthers the mandate in requiring SIs and programs to engage residents and fellows within the hospital or health system infrastructure in the use of data to improve systems of care, reduce health care disparities, and improve patient outcomes.

Notwithstanding the current requirements, clinical learning environments (CLEs) are continually deficient regarding health care disparities’ education, implementation, integration, and experiential learning.2,3 Eliminating health care disparities involves understanding the population we serve and its intersection with structural racism and SDH while working with community partners to formally assess, analyze, and prioritize the needs of the population. Programs and institutions should critically evaluate and revise policies and practices with an antiracism framework and formulate an organizational strategy that engages the health care team, including residents, faculty, and members of the community, and creates targeted interventions with accountable measures towards an ultimate goal of sustainable health equity.

As a Black female physician and designated institutional officer, I share the struggle with engaging key stakeholders in programs and across the institution in integrating these concepts and actions into the organizational fabric and day-to-day program mission and activities. Moving the needle on diversity and inclusion requires a collaborative effort and buy-in from program directors, residents, fellows, faculty, staff, and senior administration. Without that collaboration, I run the risk of being perceived as driving a self-serving agenda and creating a checkbox, or meaningless initiative that is interpreted as “one more thing to do.”

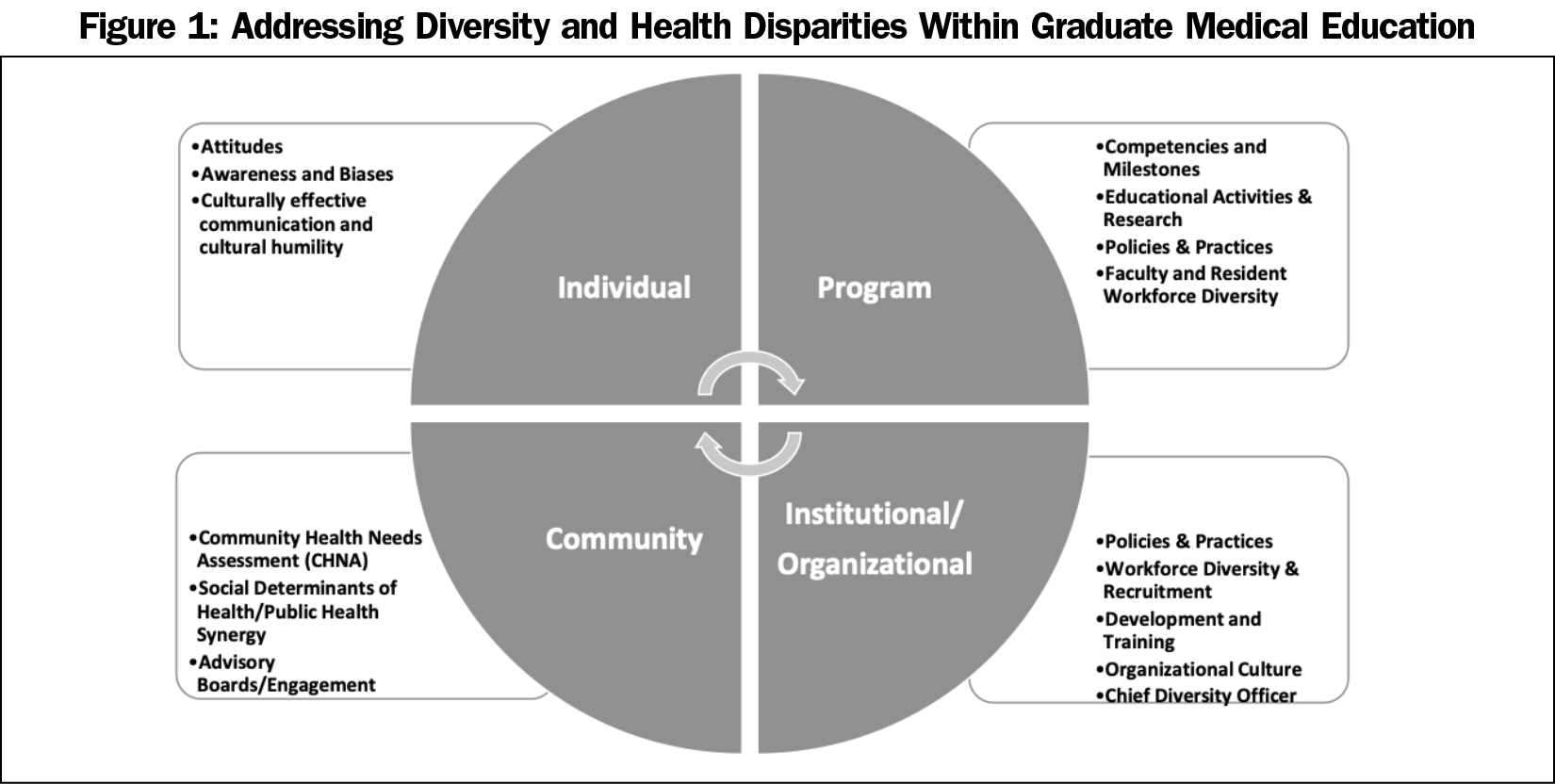

Diversity and addressing disparities must not be a checkbox or an afterthought. Programs and CLEs often feel the administrative burden and challenge of meeting regulatory and accreditation requirements. In our next set of ACGME requirements, we can promote a longitudinal and integrated framework focused on four key areas: the individual, the program, the institution/organization, and the community (Figure 1). In each of these focus areas, utilizing data is the catalyst for driving diversity and disparities change. Each area interfaces with, relies on, and is accountable to the other areas.

Transformation starts at the individual level. Each health care team member benefits from activities that promote self-awareness and self-identification of conscious and unconscious biases. Educational activities centered on implicit bias and cultural humility and competency need to be required, integrated, and longitudinal throughout residency training. As medical education leaders, we cannot bury these activities into an annually required educational module, but need to incorporate continuous, interprofessional, team-based, and experiential curricula allowing for constant awareness and reflection. The crucial goal is cultural humility with culturally effective communication that is hardwired through continuous learning and growth centered on mutual respect and accountability. The adage of “know thyself” is the first step in wholly fulfilling our oath to be healers and to care for all humankind.

Program leadership and faculty need to be empowered to develop and implement formal residency program educational activities on diversity and inclusion, reducing health care disparities, and creating health equity that are specific to the population served, incorporates practice- and population-specific data, and includes longitudinal, experiential, community-based learning that translates directly into patient care. Thereby, faculty development in these key areas is requisite. Likewise, programs should consistently engage the interprofessional team in conducting comparative analyses of current policies and practices to identify areas of disparities, gaps, and biases as it relates to patient care and to team engagement.

Training a diverse physician workforce advances health equity and is a critical component in eliminating health disparities. Resident and faculty workforce diversity is a program imperative. The growth in underrepresented minority (URM) diversity in our medical school graduates continues to lag woefully behind other race and ethnic groups. This reality has a direct impact on URM representation in residency programs and in the composition of our practicing physicians, including our faculty numbers and medical education leaders. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, medical school faculty continue to be predominantly White (64%) with only 9% URM faculty members, and significant underrepresentation at the professor and associate professor ranks. In 2019, only 6.2% of medical school graduates were Black or African American, around 5% Hispanic or Latino, 0.2% Native American or Alaska Native, and 0.1% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.4 Intentional diversity requires intentional recruitment. Strategies to recruit and retain a diverse and inclusive workforce of residents, fellows, faculty members, and staff should align with the needs of the community. Programs should define specific recruitment strategies for residents and faculty and continuously track, review, and evaluate their data and efforts to recruit and retain a diverse workforce.

Organizational diversity and graduate medical education diversity goals are not separate and distinct. A highly effective CLE and organizational culture embraces diversity by also supporting and protecting its team members with policies and practices that mitigate harassments, macroaggressions, and microaggressions through zero tolerance, team development, and training.5 As a diverse faculty and team are essential to train, mentor, and retain a diverse group of residents, organizations should also provide the resources to support the residency programs and departments in efforts to recruit and retain a diverse workforce.

GME programs are socially accountable to the communities they serve, which requires direct community engagement and integrated, collaborative curricula responsive to the unique health care needs of the diverse patient populations being served.5 The Community Health Needs Assessments is a valuable tool to integrate into program curricula making it tangible and applicable in education, practice, and quality improvement. Individuals, programs, and institutions must seek to understand local history, social and structural determinants of health, and directly involve community partners in designing a socially accountable, community-engaged diversity, equity, and inclusion curriculum. The DISCuSS model is one example that provides a framework of community engagement for curriculum development and implementation focused on health disparity. It incorporates the social accountability and diversity mandate, emphasizing the importance of inclusiveness and collaboration with community stakeholders in the curriculum development process through five steps: (1) identify gaps, (2) search literature, (3) create a module with community engagement, (4) ensure sustainability through ongoing assessments, and (5) evaluate periodically for societal alignment and social accountability.4

Advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion and eliminating health disparities through graduate medical education requires an integrated, longitudinal, multifaceted approach involving stakeholders at the individual, program, institutional/organizational, and community levels. Programs and institutions should demonstrate targeted, community-aligned, longitudinal diversity, equity, and inclusion curricula; policies and strategies for recruiting, retaining, and supporting a diverse workforce that reflect the needs of the community; and formalized diversity, equity, and inclusion faculty development. Through a well-defined, collaborative strategy with continuous process improvement, residents, faculty, and other interprofessional team members can successfully engage in a CLE that epitomizes inclusive excellence.

There are no comments for this article.