Multimorbidity is defined as the cooccurrence of two or more chronic conditions, and is sometimes described similar to complex care, or in reference to “medically complex patient populations.”1,2 Across multiple health care settings and a wide range of populations, a small number of patients account for the majority of health care expenditure. In the United States, almost 50% of the spending is by 5% of the population.3 Patients incurring these high costs have more chronic conditions and a higher rate of complex and severe conditions. Stated from the patient’s perspective, multimorbidity refers to people who have long-term conditions, living with multiple health conditions and having multiple health needs.2 People with multimorbidity have complex care needs4 and are high utilizers of medication, primary care visits, multiple specialist visits, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations.5 Rates of multimorbidity are increasing4 and will be important for family physicians of the future to address.

Patients with multimorbidity have a high risk of mortality and poorer quality of life.4 More than 50% of people who are age 65 years or older have multimorbid conditions.1 Multimorbidity increases with age, yet the total number of individuals with multimorbidity is greater in those who are less than 65 years of age than above age 65, with multimorbidity occurring 10-15 years earlier in those who are socioeconomically deprived. Mental health disorders are more prevalent as the number of physical morbidities increases and are more prevalent in more deprived than less deprived people.6,7

A systematic review of care received in the Veterans Administration (VA) system in 2010 suggests that specialist coordination, medication reconciliation, elimination of redundant testing, self-management support, and incorporating patient preference and functional ability when developing care plans is necessary in managing patients with multiple chronic conditions.3 Primary care clinicians are considered by the World Health Organization primer on multimorbidity to be best situated to meet these challenges.8 Family physicians provide comprehensive, coordinated, and person-centered care over a period of time to a defined population; this family- and community-oriented care leads to natural expertise in complex care and management of multimorbidity. Family physicians may use consultants for assistance with specific organ system-focused diseases, yet it is the family physician who can put the whole picture together, whether managing and reconciling medications, addressing the behavioral aspects that affect health, or helping connect patients to resources they need in their homes. Addressing patients’ multimorbidity needs must be embedded in family medicine residency training.

What Does Multimorbidity Care Look Like?

Care of patients with multimorbidity requires both comprehensiveness—the ability to consider and manage a broad range of problems—and continuity—the relationship that creates a deeper understanding needed to manage a patient’s unique complexity. Multimorbidity care naturally occurs in multiple settings—office/clinic, inpatient, skilled nursing facility, home care, and more. Patients with complex medical problems are the ones who most need care in different settings. One aim is to help patients and families manage their health to minimize the need for hospitalization and/or emergency department care, which also helps curb healthcare costs. However, when a patient does require hospital or emergency department care, managing the transition of care out of these settings is important to prevent future readmissions and emergency department visits during this fragile time for the patient. Care management services with communication with the patient or caregiver within 2 business days after discharge and a primary care follow-up visit with interprofessional team support can improve care and lower costs.9 This highlights that the comprehensive continuity care delivered by family physicians as part of an interprofessional team ensures the patient’s needs are met.

Patient-centered team-based care, including integrated behavioral health, care coordination, health educators, pharmacists, and other health professionals, has increased over the past few years, especially in advanced payment care models. Where practices are too small for comprehensive coordinated care, knowledge of community resources for patient referrals serves a similar function. In large or small settings, family physician practices must form networks with community partners to reduce disparities and improve access. As patient populations age and the number of conditions contributing to multimorbidity rises, family physicians need expertise in population health, learning to use robust data to manage patient panels. Patient risk stratification, based on multimorbidity data, will help family medicine practices identify patients at highest risk for whom proactive care coordination and connection to community resources could prevent multimorbidity complications. Family physicians must be able to provide equitable health care for all patients and be prepared to have meaningful discussions about quality and goals at the end of life. Family medicine practices must engage and activate patients, their family members, and their caregivers to be active partners in promoting health and improved outcomes. The ultimate aim is improved health care, improved health outcomes, and lower costs.

What Does Residency Training in Multimorbidity Look Like?

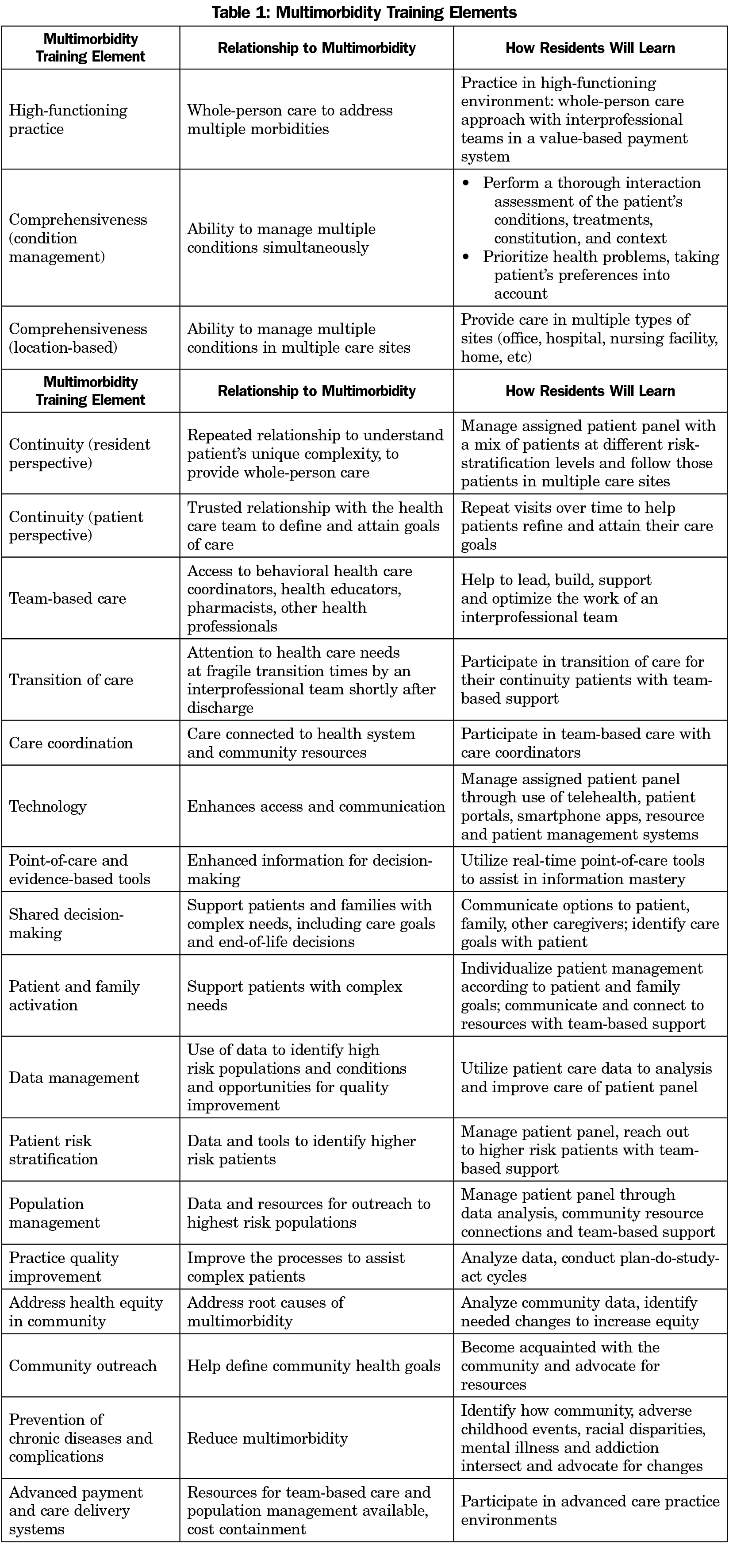

Family medicine residencies need to take the responsibility to deliberately train the family physicians of the future to be experts in tailored, patient-centered care approaches for people with multiple conditions. Table 1 lists elements of training needed to address multimorbidity, including how residents will learn. Addressing complex patient needs should be a significant focus of family medicine residency training and practice, with team-based support. Instead of patient encounters alone, resident experience should be measured by patient panel management, with patients from a mix of risk stratification levels, cared for by the resident in multiple care sites according to the patient’s needs. The concept of patient encounters should be broadened to provide increased continuity and access through telehealth, patient portals, asynchronous communications, and other resource and patient management systems. Residents who learn optimal rates and indications for referrals and to minimize polypharmacy will be learning habits leading to improved care and lower costs in their patient populations for decades to come. To successfully manage patients with multimorbidity, the fundamental skills residents must learn are to assess potential interactions of the patient’s chronic conditions, elicit patient priorities and preferences, and individualize patient management.2,10

Residents need training in high-functioning practice environments. Many of the practice building blocks designed by Bodenheimer and colleagues align with the principles needed to treat patients with multimorbidity, including comprehensiveness and care coordination, team-based care, and population management.11 While family medicine residency training should continue to be primarily ambulatory, to provide the best continuity, residents must be trained to deliver care in multiple sites, from office to hospital to home, and more. Additionally, to tackle the challenges of multimorbidity, residents must become experts in managing costs and functioning in advanced payment/delivery systems.

Beyond care for individuals with multimorbidity, residents need to understand the population they intend to serve, learn to help define health goals for their community, and connect patients to community resources for healthier living. Prevention of chronic disease and promotion of wellness to prevent multimorbidity should be incorporated into the resident’s practice. To understand the complexity and root causes of multimorbidity, residents must learn how community, adverse childhood events, racial disparities, mental illness, and addiction intersect.

In conclusion, the US population has become sicker and health care much more expensive. Family physicians, as trained experts in the four C’s of primary care—first-contact care, continuity, comprehensiveness, and coordination of care12—are particularly well positioned to address the challenges of multimorbidity, the complex care of people with multiple chronic conditions. When the next generation of family physicians are taught to be part of the solution to multimorbidity management through whole-person and interprofessional team-based care, they will be leaders in efforts to improve health care, improve health, and lower costs.

References

- Nguyen H, Manolova G, Daskalopoulou C, Vitoratou S, Prince M, Prina AM. Prevalence of multimorbidity in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Comorb. 2019;9:X19870934. doi:10.1177/2235042X19870934

- Chew-Graham C, O’Toole L, Taylor J, Salisbury C. ‘Multimorbidity’: an acceptable term for patients or time for a rebrand? Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(685):372-373. doi:10.3399/bjgp19X704681

- Zulman DM, Pal Chee C, Wagner TH, et al. Multimorbidity and healthcare utilisation among high-cost patients in the US Veterans Affairs Health Care System. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e007771. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007771

- Navickas R, Petric VK, Feigl AB, Seychell M. Multimorbidity: what do we know? What should we do? J Comorb. 2016;6(1):4-11. doi:10.15256/joc.2016.6.72

- McPhail SM. Multimorbidity in chronic disease: impact on health care resources and costs. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2016;9:143-156. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S97248

- Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380(9836):37-43. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2

- Low LL, Kwan YH, Ko MSM, et al. Epidemiologic characteristics of multimorbidity and sociodemographic factors associated with multimorbidity in a rapidly aging asian country. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1915245. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15245

- Mercer S, Furler J, Moffat K, Fischbacher-Smith D, Sanci LA. Multimorbidity: Technical Series on Safer Primary Care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

- Bindman AB, Cox DF. Changes in health care costs and mortality associated with transitional care management services after a discharge among medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(9):1165-1171. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2572

- Muth C, van den Akker M, Blom JW, et al. The Ariadne principles: how to handle multimorbidity in primary care consultations. BMC Med. 2014;12(1):223. doi:10.1186/s12916-014-0223-1

- Bodenheimer T, Gupta R, Dube K, et al. High-Functioning Primary Care Residency Clinics: Building Blocks for Providing Excellent Care and Training. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2016. https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/126/. Accessed May 27, 2021.

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x