Social accountability is the measure of institutional response to society’s needs. It is often used to frame government accountability to its citizens, but it is also highly applicable to institutions of medicine. For health care to be socially accountable, it must be equitably accessible to everyone and responsive to patients, community, and population health needs.1 For graduate medical education (GME) to be socially accountable, institutions must commit to training graduates who can work collaboratively with communities, governments, health systems, and the public to address health disparities and contribute to adapting the health system to better meet community needs. Bold and expansive thinking and transformational change in GME will not occur if we only tinker with the existing GME structure. We can meet this challenge by aligning all components of GME. In this paper, we specifically discuss how GME can become more accountable to community needs by addressing GME funding systems, institutional and residency-level accreditation systems, and family medicine residency programs.

SPECIAL ARTICLES

Social Accountability and Graduate Medical Education

Arthur Kaufman, MD | Mary Alice Scott, PhD | John Andazola, MD | Danielle Fitzsimmons-Pattison, MD | Laura Parajón, MD, MPH

Fam Med. 2021;53(7):632-637.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2021.160888

Because graduate medical education (GME) is largely publicly funded, it should be judged on how well it addresses the public’s health needs. However, the current system distributes GME resources inequitably by specialty and geography, and neglects to focus on training physicians adequately in the care of populations while reducing health disparities. Instead, GME continues to concentrate training in hospital-based academic centers and in subspecialties, which often exacerbates disparities in health outcomes and access to care. GME can be more socially accountable by shifting incentive structures to support primary care, creating more equitable distribution of residency slots and funding, and promoting training programs that focus on social and structural determinants of health.

In order to have substantial and sustainable change toward social accountability, the funding system must incentivize medical education that meets community health needs. Current policies and practices of funding for GME are poorly aligned with community needs, although most GME funding is public. Funding the most needed specialties in the most medically underserved areas has not been a priority. Since 1965, Medicare and Medicaid have been the largest source of financial support to residency programs nationwide followed by Veterans Affairs (VA) and Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), all costing the public billions of dollars annually. The most recent estimated cost was nearly $19 billion—$12.5 billion from Medicare, $4.2 billion from Medicaid, $1.75 billion from the VA, and $451 million from HRSA.2 Taxpayers have a right to scrutinize the outcome of their investment. However, Medicare GME payments are hospital-centric, formula-based, and not tied to local or national community needs. The requirement that residency programs be accredited in order to receive this public funding is one of the few accountability mechanisms that currently exist.3 The 2014 Institute of Medicine report, Graduate Medical Education that Meets the Nation’s Health Needs, called for both transparency in where GME funds were spent, and accountability as to how funds were targeted.3 Unfortunately, these recommendations were mostly ignored, and current federal policy makes changing the focus of GME funding challenging.

Compounding the problem, the Balanced Budget Act capped the number of Medicare-funded residency positions in 1997. Hospitals can expand residency programs beyond the cap but will not receive additional Medicare payments for these trainees. Thus, clinical departments must self-fund residency positions exceeding the cap. This leads to a disproportionate growth of better-funded subspecialties compared to currently less profitable specialties such as primary care. In a 5-year period after the passage of the Balanced Budget Act, subspecialty training grew at a ratio of 5:1 compared to primary care.4

Such cost control measures do not necessarily support improved community health outcomes. An increased ratio of primary care physicians to specialists in a community increases overall health, decreases cost,5 and is associated with increased life expectancy.6 Still our current GME system does not train enough primary care physicians, nor does it train them in the places where they are most needed. In 2019, only 9% of residents in all Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) training programs nationwide were training in family medicine.7 Family medicine is the specialty that most closely mirrors the rural/urban distribution of the general population. Significantly, family physicians represent the largest proportion of primary care physicians in rural areas.8 While internal medicine does provide some primary care physicians, the vast majority of internal medicine residents subspecialize.9 Pediatrics follows a similar trend.10

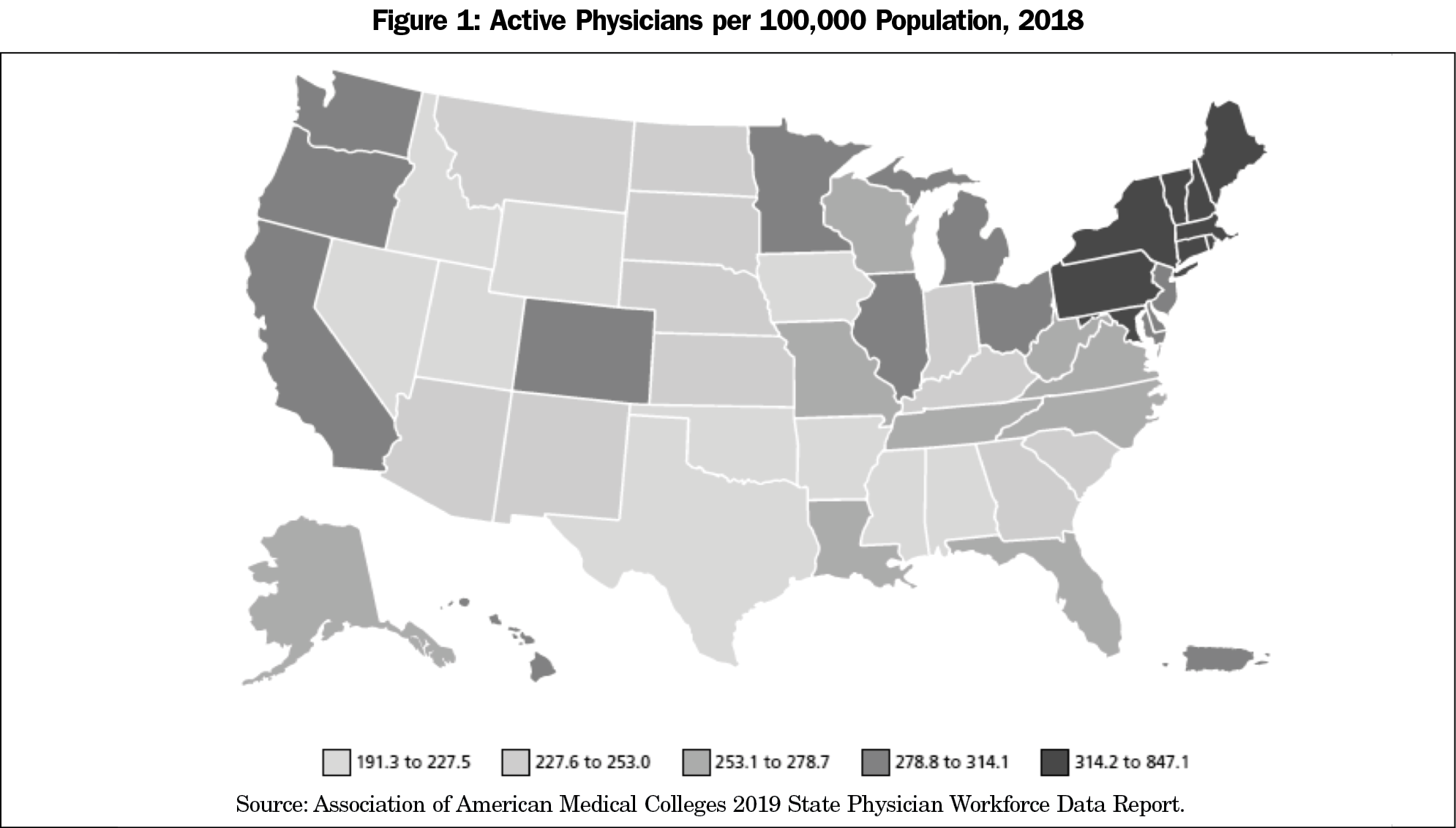

Currently, Medicare-funded GME resources are also disproportionately concentrated in the northeastern states (Figure 1). These states have more physicians, more Medicare-funded GME slots, and more funding for those slots per 100,000 population. For example, Montana has 1.63 Medicare-sponsored residency slots per 100,000 population while New York has 77.13. Similarly, Louisiana’s residents are funded at $63,811 per resident per year, while Connecticut’s are funded at $155,135.11

This maldistribution of training positions and funding leads to inequitable distribution of physicians. New York and Massachusetts not only have some of the highest numbers of Medicare-funded GME slots in the nation but also have the highest physician density per 100,000 population. This contrasts with Wyoming and Idaho that have some of the fewest GME slots per 100,000 population as well as the lowest physician density in the nation.

In addition, only DME (Direct Graduate Medical Education funding), not IME (Indirect Graduate Medical Education funding), funds GME in community settings, even though this is where most health care takes place. Full funding, including both DME and IME, only applies to training in teaching hospitals or at teaching hospital-affiliated clinics.3

In 45 states and the District of Colombia, over $4 billion of Medicaid funds are spent to support GME annually. Unfortunately, Medicaid GME is largely directed in a manner similar to Medicare GME, with a formula-based, hospital-centric distribution of funds. Only a few states direct all or some of these payments to address primary care shortages or underserved communities.12 States can utilize Medicaid to create community-based GME programs that meet community needs.13,14 In order to do this, state governments need to uncouple Medicaid GME dollars from Medicare GME allocation formulas. States have more direct control of how these funds are spent and thus can create state-based, socially-accountable GME programs in their own communities while directing these funds toward the greatest health care and workforce needs of the state.12

Congress should act to direct the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to address the lack of social accountability that exists in the current funding method of graduate medical education. They must utilize the reports available to them such as the 2014 National Academies of Medicine (previously Institute of Medicine) report Graduate Medical Education That Meets the Nation’s Health Needs. Congress should direct CMS to build a new GME financial infrastructure with focus on these recommendations:

Recommendation 1a

CMS should offer clear guidelines regarding budgetary accountability for how GME funds are spent that are consistent with the use of public funding to meet community needs.

Recommendation 1b

CMS should set national goals to incentivize primary care, particularly family medicine, to address community needs nationwide.

Recommendation 1c

CMS should utilize data on residency program graduate specialty, practices, and location to target funding toward meeting societal needs for specific specialties where they are needed.

Recommendation 1d

CMS should allow nonhospital venues (Federally Qualified Health Centers, Rural Health Clinics, Indian Health Services) access to GME funding to train residents in community settings where the majority of care takes place..

States should utilize Medicaid to create state-based GME funding designed to meet community needs.

Recommendation 2a

State governments should uncouple Medicaid GME dollars from Medicare GME allocation formulas in order to accomplish this.

In addition to realigning GME funding toward needed specialties in underserved areas, changes are also needed in accreditation policies for training institutions and residency programs to improve social accountability. The ACGME’s concern is predominantly focused on quality in education of and service by residents within hospital and clinic walls. But how is quality defined? Advanced models do exist in other countries. Canada, for example, has developed a set of guiding principles for medical education that explicitly includes social accountability. This model, endorsed by all Canadian faculties of medicine, focuses on community health and social determinants of health equity. It is part of a global movement supported by the World Health Organization.15,16

In the United States, similar efforts have not been as strongly endorsed. In 2010, Mullan et al published medical school rankings on social responsibility; by aligning metrics with global social accountability efforts, the report upended traditional methods of ranking medical schools.17 Key criteria defining social ranking included number of graduates in primary care, working in underserved communities, and representing underrepresented minorities. Many of the usually top-ranked medical schools fell toward the bottom in social responsibility rankings. The authors faced great criticism, especially from leaders of institutions accustomed to high rankings on traditional measures of research grants, selectivity, national board scores, and peer recognition, all of which correlated poorly with the degree to which graduates serve in the most needed specialties in the communities with most need. While these new rankings were applied to undergraduate medical education, a similar model could be adapted to assess social accountability in graduate medical education. The ACGME has made some progress in addressing social accountability in medical education, although it does not as fully embrace the social accountability principles that the Canadian model does.18

The ACGME’s diversity initiative includes common program requirements that have the potential to address social accountability. These requirements include that programs address recruitment and retention of a diverse and inclusive workforce, that program directors create an environment that facilitates residents’ ability to raise concerns without fear, that programs address evaluation so as not to rely on first-time board pass rates as a measure of program excellence, and that programs and sponsoring institutions create a professional and respectful environment.19 These requirements speak to the need to think critically about program and institutional cultures to ensure inclusivity and support for diversity in general, but they do not directly address the inclusion of groups that represent the communities they serve. The ACGME does provide resources and forums for sharing program-specific initiatives, but specific requirements remain vague. Thus, they are insufficient to fully support increased diversity of the physician population.

In addition, through the Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) program’s Pathways to Excellence, the ACGME provides a framework for achieving health care quality. One of the components of the framework is a recommendation that residents, fellows, and faculty members engage in clinical site initiatives to eliminate health care disparities.20 However, the 2016 and 2019 CLER National Reports of Findings cited that few clinical learning environments were engaged in comprehensive efforts to identify and eliminate health care disparities. It was uncommon for residents, faculty members, or program directors to be involved in these efforts.21,22 The efforts the ACGME is taking to address health disparities must be sustained and strengthened as health care disparities persist.

The ethnic distribution in the US population is shifting rapidly, such that within two decades, a majority of our population will be Hispanic/Latino, African American, Asian, Native American and mixed ethnicity. However, the ethnicity of medical students and thus, residents, has not kept pace. This ethnic disparity between physicians and patients portends a negative health impact.23 Ethnic minority physicians are five times more likely to see ethnic minority patients than are non-Hispanic white physicians,23 and the concordance of race/ethnicity between physicians and patients leads to better health outcomes.24 In addition, underrepresented minority physicians are more likely to work in underserved communities.25

Equally alarming is the fact that as the nation’s wealth is increasingly concentrated in the top 1% of the population, the vast majority of Americans have made far fewer economic gains in real terms. Yet, incoming US medical students’ family income has remained steadily in the upper income quintiles, further distancing the socioeconomic life experience of future physicians from that of their patients and communities.26 This disparity could further exacerbate the geographic maldistribution of the physician workforce in the future. To be socially accountable, we need to train physicians that reflect the demographic mix of the communities they serve.

The ACGME must expand current competencies to more fully address the community forces, assets, and challenges that affect the health of individuals and communities. The ACGME, as an accreditor, can play an important role building social accountability in GME by requiring monitoring of the impact of GME on community health.27 ACGME should set standards for and require measures of social accountability in institutional accreditation standards, specifically focusing on the following recommendations.

The ACGME should further develop its institutional requirements to specifically strive for resident racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity that mirrors the diversity of the community the program serves.

The ACGME should strengthen the requirements for institutions to utilize community health needs and demographic data as part of institutional and residency accreditation requirements.

The ACGME should strengthen systems-based practice or develop a new competency that specifically addresses health disparities.

To fully achieve social accountability, family medicine training programs must also respond to the specific community needs where their programs are located. In reality, medical care explains only about 10% of the premature deaths in the United States, whereas social and structural determinants of health account for more than 60%.28 While these determinants of health are common across settings at a macro level, there are local nuances that primary care physicians will need to know in order to effectively address community health needs. However, current training is skewed toward academic teaching hospitals, which limits residents’ exposure to the complexity of health equity in communities, including both its assets and challenges. To fulfill our goal of social accountability, we need to think beyond traditional expectations as to where residents train and who trains them.29 We need to consider a broader array of teachers and role models with expertise and a track record for addressing social and structural factors that contribute to health inequities, from social scientists to community health workers. We acknowledge that there are programs with long histories of doing this type of training, however these models are not yet standard for all training programs.

For example, community health workers have been shown to be effective trainers of social determinants to family medicine residents.30 Health extension agents have made a major contribution in linking community health needs with university resources in education, service and research.14 Social scientists have played a central role in training physicians to be accountable to their communities and to ensuring that residency programs are outward facing and responsive to community needs.31

Just as health professionals learn to interpret and address abnormal vital signs, family physicians must now learn to ask about key social determinants of health and address adverse findings. In one study of a network of university and community health centers, 50% of all primary care clinic patients screened for 11 common social determinants had at least one adverse social determinant. Half of those had more than one; many had five or six. This important data was virtually unknown to the clinic or providers because this vital information is not routinely collected.32 Additionally, when primary care clinics hire community health workers (CHWs) to address social determinants, Medicaid-managed care organizations observed higher quality and lower cost for their enrollees.33 CHW presence is also a benefit to residents who now learn to practice with a health team providing more comprehensive care.

Additionally, because family medicine training is so heavily focused upon a hospital-based venue, we must find ways of bringing social accountability to life for residents in the inpatient setting. Residents come face to face with health equity issues experienced by their patients daily—whether this entails inequity in access to clinical services, in educational opportunities, in access to nutritious food, or in available transportation. Further, residents often hospitalize patients whose admissions could have been prevented if we addressed such health inequities. In one program, residents on ward teams learned to identify and address health policy challenges simply by asking about each patient, “How could this admission have been prevented?” The outcome included a range of policy changes from reinstallation of taxi vouchers in the ED to the addition of weekend pharmacy hours for the working poor.34 The Family Medicine Residency Review Committee (FM-RCC) should consider the following recommendations.

Family medicine faculty should be broadened to include social scientists.

Family medicine training should be broadened to include more contributors to the health care team, including community health workers and health extension agents.

Residency curriculum should be relevant to the unique geographic and social context of the communities to which programs are responsible.

Recommendation 8a

Extensive exposure to community-based learning experiences that develop a resident’s understanding of, and ability to act upon, social determinants should be required. Particular emphasis should be placed on vulnerable populations.

Recommendation 8b

Scholarly activity in residency programs should be directed and inspired by the local community’s health needs.

The FM-RRC should require evaluation of the skill sets of graduates applicable to community needs and track locations of graduate practices.

Rethinking and reforming GME to better serve the needs of community health and fulfill the demands of social accountability will require reexamination of the funding, accreditation, and physician training in our graduate medical education system. In order for substantial and sustained change leading to a graduate medical education system that is socially accountable, funding reform must be at the forefront. Congress must direct CMS to reform the current Medicare-GME funding system to produce physicians trained to meet community needs. This new system must be data-driven and transparent.

The physicians produced by this GME system must be adequately prepared to address the inequities that exist in our communities and they must represent the racial, ethnic, cultural, and socioeconomic diversity of the communities they serve. The ACGME must continue and further develop its efforts to promote diversity. It should additionally require accountability in institutional accreditation based on community needs data and further develop competencies that specifically address health disparities. In addition, the FM-RRC should further prepare graduates to address health equity concerns by requiring residency programs to increase their health equity training in community settings, involving experts such as social scientists and community health workers. We believe this transformation is not only possible, but essential to the future health of the United States.

References

- Buchman S, Woollard R, Meili R, Goel R. Practising social accountability: from theory to action. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(1):15-18.

- Congressional Research Service. Federal support for graduate medical education: An Overview. Congressional Research Service Report R44376. 2018.

- Committee on the Governance and Financing of Graduate Medical Education; Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine; Eden J, Berwick D, Wilensky G, editors. Graduate Medical Education That Meets the Nation's Health Needs. Washington, D: National Academies Press; 2014 Sep 30. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK248027/. Accessed March 22, 2021.

- Salsberg E, Rockey PH, Rivers KL, Brotherton SE, Jackson GR. US residency training before and after the 1997 Balanced Budget Act. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1174-1180. doi:10.1001/jama.300.10.1174

- Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi I. Contribution of primary care systems to health outcomes within Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, 1970-1998. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457-502.

- Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Phillips RL, Bitton A, Landon BE, Phillips RS. Association of primary care physician supply with population mortality in the United States, 2005-2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(4):506-514. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7624

- Association of American Medical Colleges. ACGME Residents and Fellows by Sex and Specialty, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/interactive-data/acgme-residents-and-fellows-sex-and-specialty-2019. Accessed February 23, 2021.

- Petterson S, McNellis R, Klink K, Meyers D, Bazemore A. The State of Primary Care in the United States: A Chartbook of Facts and Statistics. Washington, DC: The Roberth Graham Center; 2018. https://www.graham-center.org/content/dam/rgc/documents/publications-reports/reports/PrimaryCareChartbook.pdf. Accessed February 23, 2021.

- American Board of Internal Medicine. Number of Candidates Certified Annually by the American Board of Internal Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: ABIM. https://www.abim.org/~/media/ABIM%20Public/Files/pdf/statistics-data/candidates-certified-annually.pdf. Accessed February 23, 2021

- Dalen JE, Ryan KJ, Alpert JS. Where have the generalists gone? They became specialists, then subspecialists. Am J Med. 2017;130(7):766-768. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.01.026

- Mullan F, Chen C, Steinmetz E. The geography of graduate medical education: imbalances signal need for new distribution policies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(11):1914-1921. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0545

- Rockey PH, Rieselbach RE, Neuhausen K, et al. States Can Transform Their Health Care Workforce. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(4):805-808. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-14-00502.1

- Newton WP, Bazemore A, Magill M, Mitchell K, Peterson L, Phillips RL. The future of family medicine residency training is our future: A call for dialogue across our community. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33(4):636-640. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2020.04.200275

- Kaufman A, Alfero C. A state-based strategy for expanding primary care residency. Health Affairs Blog. July 31, 2015. doi:10.1377/hblog20150731.049707

- Rourke J. Social accountability: a framework for medical schools to improve the health of the populations they serve. Acad Med. 2018;93(8):1120-1124. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002239

- Marmot M, Allen JJ. Social determinants of health equity. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(S4)(suppl 4):S517-S519. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302200

- Mullan F, Chen C, Petterson S, Kolsky G, Spagnola M. The social mission of medical education: ranking the schools. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(12):804-811. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-152-12-201006150-00009

- Reddy AT, Lazreg SA, Phillips RS. Toward defining and measuring social accountability in graduate medical education: A Stakeholder’s study. J Grad Med Ed 2013; 5(3):439-440.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Diversity-Equity-and-Inclusion. Accessed February 25, 2021.

- CLER Evaluation Committee. CLER pathways to excellence: Expectations for an optimal clinical learning environment to achieve safe and high-quality patient care, version 2.0. Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2019. doi:10.35425/ACGME.0003

- Wagner R, Koh NJ, Patow C, et al. Detailed findings from the CLER national report of findings 2016. J Grad Med Educ Suppl. May 2016.

- Co JPT, Weiss KB, Koh NJ, et al. CLER national report of findings 2019: Initial visits to sponsoring institutions with 2 or fewer core residency programs. [executive summary] Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2019. doi:10.35425/ACGME.0002

- Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, Bindman AB. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(9):997-1004. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.9.997

- Alsan M, Garrick O, Graziani G. Does diversity matter for health? Experimental evidence from Oakland. Am Econ Rev. 2019;109(12):4071-4111. doi:10.1257/aer.20181446

- Metz AM. Medical school outcomes, primary care specialty choice, and practice in medically underserved areas by physician alumni of MEDPREP, a postbaccalaureate premedical program for underrepresented and disadvantaged students. Teach Learn Med. 2017;29(3):351-359. doi:10.1080/10401334.2016.1275970

- Youngclaus J, Roskovensky L. An updated look at the economic diversity of U.S. medical students. AAMC Analysis in Brief. Oct 2018 18(5).

- Castillo EG, Isom J, DeBonis KL, Jordan A, Braslow JT, Rohrbaugh R. Reconsidering systems-based practice: advancing structural competency, health equity, and social responsibility in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2020;95(12):1817-1822. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003559

- Schroeder SA. Shattuck Lecture. We can do better—improving the health of the American people. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(12):1221-1228. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa073350

- Hunt JB, Bonham C, Jones L. Understanding the goals of service learning and community-based medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2011;86(2):246-251. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182046481

- McCalmont K, Norris J, Garzon A, et al. Community health workers and family medicine resident education: addressing the social determinants of health. Fam Med. 2016;48(4):260-264.

- Scott MA, Moralez E, Andazola J, et al. Integrating health equity across a family medicine residency program: anthropology as a solution to a stubborn problem. In: Martinez I, Weidman D, eds. Anthropology in Medical Education. Springer; in press.

- Page-Reeves J, Kaufman W, Bleecker M, et al. Addressing social determinants of health in a clinic setting: the WellRx pilot in Albuquerque, New Mexico. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(3):414-418. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2016.03.150272

- Johnson D, Saavedra P, Sun E, et al. Community health workers and medicaid managed care in New Mexico. J Community Health. 2012;37(3):563-571. doi:10.1007/s10900-011-9484-1

- Jacobsohn V, DeArman M, Moran P, et al. Changing hospital policy from the wards: an introduction to health policy education. Acad Med. 2008;83(4):352-356. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181667d6e

Lead Author

Arthur Kaufman, MD

Affiliations: University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM

Co-Authors

Mary Alice Scott, PhD - New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM

John Andazola, MD - Memorial Medical Center, Southern New Mexico Family Medicine Residency Program, Las Cruces, NM

Danielle Fitzsimmons-Pattison, MD - Southern New Mexico Family Medicine Residency Program, Las Cruces, NM

Laura Parajón, MD, MPH - University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM

Corresponding Author

Mary Alice Scott, PhD

Correspondence: Department of Anthropology, New Mexico State University, 1525 Stewart St, Breland Hall, Rm 331, Las Cruces, NM 88003. 575-646-5935.

Email: mscott2@nmsu.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.