Background and Objectives: Professionalism is essential in medical education, yet how it is embodied through medical students’ lived experiences remains elusive. Little research exists on how students perceive professionalism and the barriers they encounter. This study examines attitudes toward professionalism through students’ written reflections.

Methods: Family medicine clerkship students at Stanford University School of Medicine answered the following prompt: “Log a patient encounter in which you experienced a professionalism challenge or improvement opportunity.” We collected and analyzed free-text responses for content and themes using a grounded theory approach.

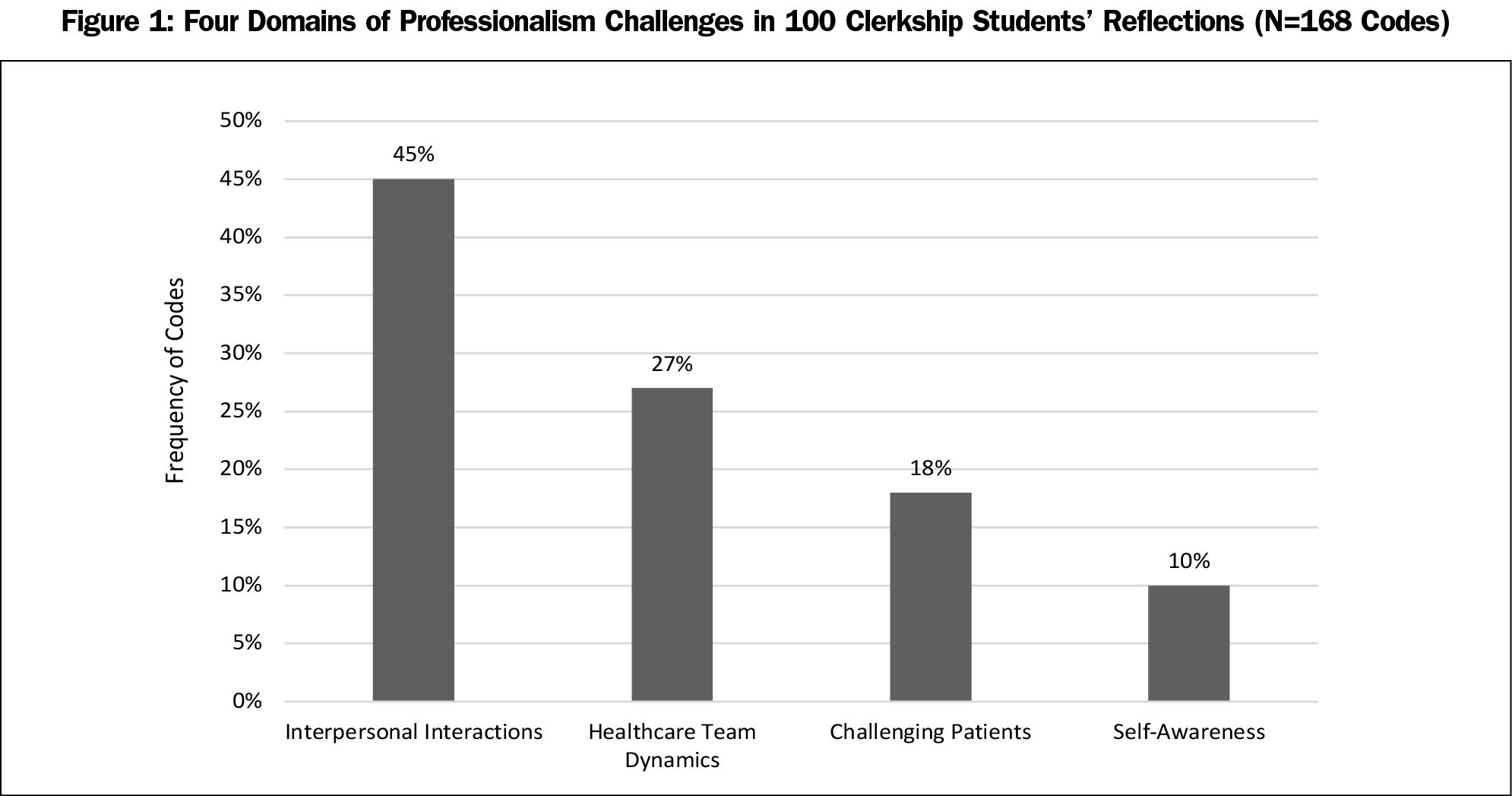

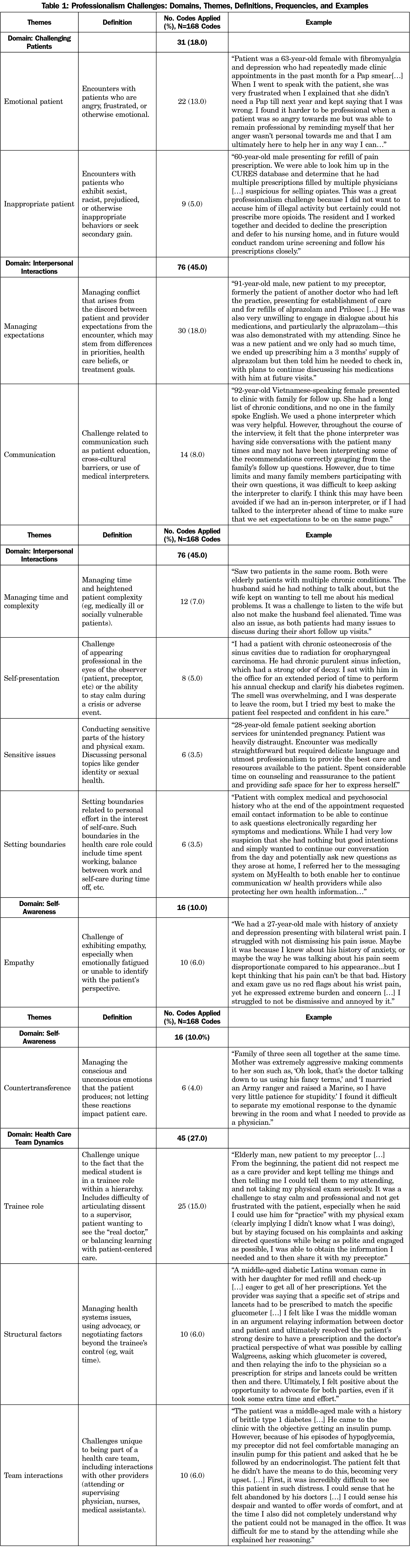

Results: One hundred responses from 106 students generated a total of 168 codes; 13 themes emerged across four domains: challenging patients, interpersonal interactions, self-awareness, and health care team dynamics. The three most frequently occurring themes were interacting with emotional patients, managing expectations in the encounter, and navigating the trainee role.

Conclusions: Medical students view professionalism as a balance of forces. While many students conceived of professionalism in relation to patient encounters, they also described how professionalism manifests in inner qualities as well as in health systems. Interpersonal challenges related to communication and agenda-setting are predominant. Systems challenges include not being seen as the “real doctor” and being shaped by team behaviors through the hidden curriculum. Our findings highlight salient professionalism challenges and identity conflicts for medical students and suggest potential educational strategies such as intentional coaching and role-modeling by faculty. Overall, students’ reflections broaden our understanding of professional identity formation in medical training.

Professionalism remains a salient topic in medical education, yet it eludes definition.1,2 The American Board of Family Medicine defines professionalism as “shared competency standards and ethical values” including a commitment to serve patients, continued enhancement of one’s skills, fairness and honesty, contributing to public good, and accepting responsibility.3 However, idealized language does not reflect the “situatedness of students’ experiences” in the real world.4,5 Clerkship students offer an opportunity to study professionalism in medical training.

Medical students encounter professionalism education in both planned and hidden curricula.6–8 Professionalism is often taught through its inverse: videos of poor behavior, lists of what not to do, and fears of evaluation that flatten a complex dialogue.9–12

Participants

Study participants were third- and fourth-year medical students from Stanford University School of Medicine on their required 4-week family medicine clerkship. Clerkship sites encompassed 12 academic, urban, suburban, and rural outpatient clinics in Northern California.

Data Collection

Stanford medical students submit patient logs aligned with Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Core Competencies. One entry prompts them to “Log a patient encounter in which you experienced a professionalism challenge or improvement opportunity.” We compiled deidentified responses through the medical school’s evaluation web software, E*Value, from students who completed the clerkship from February 2016 through April 2018, excluding entries that did not attempt to answer the question, resulting in 100 responses. Because we used preexisting data without human subject identifiable information, Stanford University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) exempted this study from formal review.

Analysis

A resident physician and anthropologist (A.M.) and a family medicine faculty member (E.S.) analyzed the data. Using grounded theory, transcripts were coded inductively over four rounds, using open coding to develop comparisons and produce conceptual categories across similar events until thematic saturation was reached. The first round of coding was done independently to increase reliability. Coding disagreements were subsequently adjudicated through discussion, and the codebook was developed iteratively in each round.18 Both raters coded all responses with the last round completed using the stable, finalized codebook.

We applied a total of 168 codes across 100 transcripts (each transcript receiving at least one code; average of 1-2 codes per response). Thirteen themes emerged from student responses which were categorized across four domains. The initial interrater reliability pooled Cohen’s ϰ score was 0.6 for the first phase and 0.87 for the second phase. This improved to 100% interrater agreement after negotiated consensus through feedback and discussion.

One hundred-six medical students submitted responses to the prompt over the study period. Six responses were excluded as they did not answer the question, resulting in 100 essay transcripts and a 94% response rate. Thirteen themes emerged within four domains: challenging patients, interpersonal interactions, self-awareness, and health care team dynamics (Figure 1). Three themes comprised almost half of all code applications—77 of 168 codes (46.0%): (1) emotional patients, (2) managing expectations, and (3) trainee role. Definitions, frequencies, and examples of each theme are elaborated in Table 1.

Challenging Patients

Emotional patients and inappropriate patients were cited as challenging archetypes. Emotional patients brought heightened feelings or distress into the encounter. Inappropriate patients crossed boundaries, made sexist or racist remarks, or otherwise behaved in ways that made it difficult to proceed with usual physician-patient roles.

Interpersonal Interactions

Interpersonal challenges formed the broadest domain; students highlighted communication, time management, and conflict resolution as useful skills. Managing expectations entailed reconciling the patient’s agenda. Managing time and complexity arose with complex patients, interpreters, or family members present. Self-presentation was the challenge of maintaining equanimity under duress. Sensitive issues related to patients’ personal challenges or identity markers like gender or sexual orientation. Setting boundaries manifested in communicating limits of the health care role.

Self-awareness

The domain of self-awareness centered on managing internal reactions—empathy and countertransference—and processing emotion within the encounter. The challenge of empathy arose in situations that made it difficult to see the patient’s perspective. In countertransference, students negotiated conscious and unconscious emotional reactions in response to patients.19

Health Care Team Dynamics

Challenges related to health care team dynamics included the nature of the medical student role and interactions with other providers. The unique challenges of the trainee role ranged from not being viewed by patients as the real doctor to facing disempowerment in the hierarchy of supervision. Structural factors encompassed barriers like clinic logistics, difficulties accessing care, or advocacy. Challenges related to team interactions arose in visits including the attending or other providers, where trainees walked the line between individual ethics and fitting in.

This study highlights medical student perspectives on professionalism and broadens our understanding of professional identity formation in training. Students’ reflections encompassed patients, as hypothesized, and also displayed how professionalism manifests through inner qualities and within health care systems.20 Students conceptualized professionalism as a balance of forces, whether in reconciling the patient’s perspective, maintaining self-awareness in emotionally-demanding situations, or navigating teams. This study focuses on a small sample from one medical school involving both third- and fourth-year students and is therefore limited in generalizability. No definition of professionalism was provided, which may have resulted in varying interpretations.

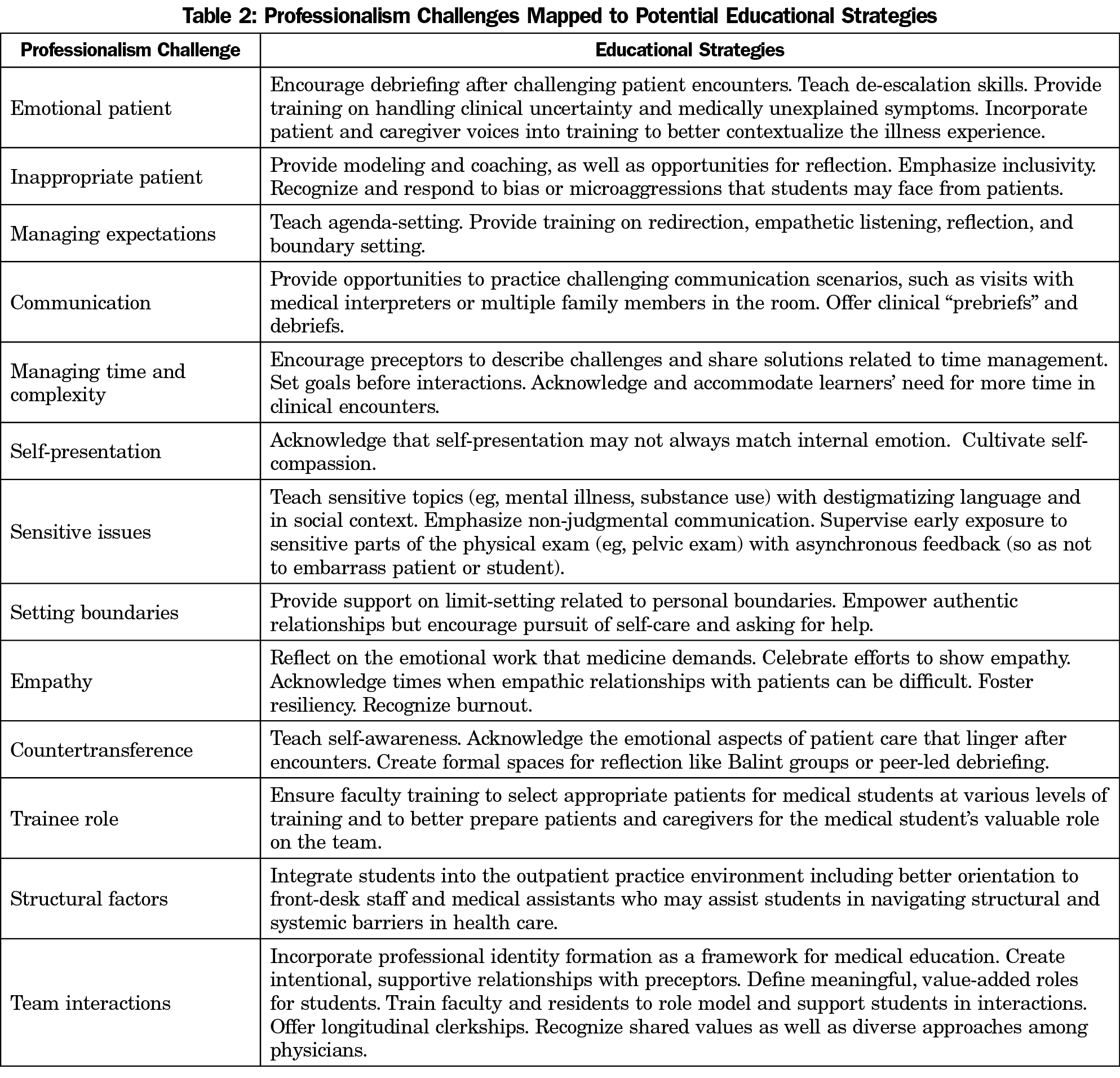

Our analysis reveals the pervasiveness of professional identity conflicts in medical training. Internally, being too much oneself or too little is a challenge of emotional modulation. Interpersonally, communication remains an area of desired development.21 Externally, not being seen as the real doctor interferes with confidence and growth, and the hidden curriculum22–24 including role-modeling by faculty shape values.25 We suggest potential educational strategies to mitigate these challenges (Table 2). Overall, integrating a framework for professional identity formation may give students a language to reflect, refine skills, and balance competing forces on the journey of becoming a physician.

References

- Swick HM. Toward a normative definition of medical professionalism. Acad Med. 2000;75(6):612-616. doi:10.1097/00001888-200006000-00010

- Birden H, Glass N, Wilson I, Harrison M, Usherwood T, Nass D. Defining professionalism in medical education: a systematic review. Med Teach. 2014;36(1):47-61. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2014.850154

- American Board of Family Medicine. Guidelines for Professionalism, Licensure, and Personal Conduct. https://www.theabfm.org/sites/default/files/PDF/ABFMGuidelines.pdf. Lexington, KY: ABFM; 2019. Accessed June 1, 2019.

- Ginsburg S, Regehr G, Stern D, Lingard L. The anatomy of the professional lapse: bridging the gap between traditional frameworks and students’ perceptions. Acad Med. 2002;77(6):516-522. doi:10.1097/00001888-200206000-00007

- Salinas-Miranda AA, Shaffer-Hudkins EJ, Bradley-Klug KL, Monroe AD. Student and resident perspectives on professionalism: beliefs, challenges, and suggested teaching strategies. Int J Med Educ. 2014;5:87-94.

- Bagg W, Clark K. Professionalism: medical students, future practice and all of us. Intern Med J. 2017;47(2):133-134. doi:10.1111/imj.13320

- Mossop L, Dennick R, Hammond R, Robbé I. Analysing the hidden curriculum: use of a cultural web. Med Educ. 2013;47(2):134-143. doi:10.1111/medu.12072

- Kao A, Lim M, Spevick J, Barzansky B. Teaching and evaluating students’ professionalism in US medical schools, 2002-2003. JAMA. 2003;290(9):1151-1152.

- Mak-van der Vossen M, van Mook W, van der Burgt S, et al. Descriptors for unprofessional behaviours of medical students: a systematic review and categorisation. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):164. doi:10.1186/s12909-017-0997-x

- Leo T, Eagen K. Professionalism education: the medical student response. Perspect Biol Med. 2008;51(4):508-516. doi:10.1353/pbm.0.0058

- Brainard AH, Brislen HC. Viewpoint: learning professionalism: a view from the trenches. Acad Med. 2007;82(11):1010-1014. doi:10.1097/01.ACM.0000285343.95826.94

- Lucey C. The Problem With Professionalism. In: Byyny RL, Papadakis MA, Paauw DS, eds. Medical Professionalism: Best Practices. Menlo Park, CA: Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society; 2015:9-21.

- Irby DM, Hamstra SJ. Parting the clouds: three professionalism frameworks in medical education. Acad Med. 2016;91(12):1606-1611. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001190

- Gaufberg EH, Batalden M, Sands R, Bell SK. The hidden curriculum: what can we learn from third-year medical student narrative reflections? Acad Med. 2010;85(11):1709-1716. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181f57899

- Roper L, Foster K, Garlan K, Jorm C. The challenge of authenticity for medical students. Clin Teach. 2016;13(2):130-133. doi:10.1111/tct.12440

- Sternszus R. Developing a professional identity: a learner’s perspective. In: Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y, eds. Teaching Medical Professionalism. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2016:26-36. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316178485.004

- Ratanawongsa N, Bolen S, Howell EE, Kern DE, Sisson SD, Larriviere D. Residents’ perceptions of professionalism in training and practice: barriers, promoters, and duty hour requirements. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(7):758-763. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00496.x

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual Sociol. 1990;13(1):3-21. doi:10.1007/BF00988593

- Hughes P, Kerr I. Transference and countertransference in communication between doctor and patient. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2000;6(1):57-64. doi:10.1192/apt.6.1.57

- Irby D. Constructs of professionalism. In: Byyny RL, Paauw DS, Papadakis MA, Pfeil S, eds. Medical Professionalism Best Practices: Professionalism in the Modern Era. Menlo Park, CA: Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society; 2017:9-14.

- Braverman G, Bereknyei Merrell S, Bruce JS, Makoul G, Schillinger E. Finding the words: medical students’ reflections on communication challenges in clinic. Fam Med. 2016;48(10):775-783.

- Glicken AD, Merenstein GB. Addressing the hidden curriculum: understanding educator professionalism. Med Teach. 2007;29(1):54-57. doi:10.1080/01421590601182602

- Creuss RL, Sylvia R. Cruess, Steinert Y, editors. Teaching Medical Professionalism, 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press; 2016.

- White CB, Kumagai AK, Ross PT, Fantone JC. A qualitative exploration of how the conflict between the formal and informal curriculum influences student values and behaviors. Acad Med. 2009;84(5):597-603. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819fba36

- Steinauer JE, Teherani A, Preskill F, Ten Cate O, O’Sullivan P. What do medical students do and want when caring for “difficult patients”? Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(3):238-249. doi:10.1080/10401334.2018.1534693

There are no comments for this article.