Background and Objectives: Family medicine residency program directors (PD) oversee the training of every new family physician in the United States. The median tenure of family medicine PDs is 4.5 years, and factors relating to length of tenure and reasons for departure are not well known. This exploratory study examined why family medicine PDs leave their position.

Methods: We conducted in-depth interviews with family medicine PDs who recently left their director position. Semistructured and structured questions asked about their PD experience and factors contributing to stepping away from the PD role. We analyzed answers quantitatively and qualitatively.

Results: When comparing cases with longer (>6 years) and shorter tenures (≤6 years), 25 PDs described differing pathways but few major differences in why they left the position. The two groups were distinguished more by their similarities than their differences. The majority left voluntarily due to a combination of factors, not a single factor. Most PDs left the position because of their desire and opportunities to move up, move over, or move on, and not because of dissatisfaction with the job. Succession plans helped with PD decisions to leave the position, knowing that the program was in good hands.

Conclusions: Family medicine PDs left the position due to multiple factors primarily related to career pathway choices and not solely due to demands of the job. Additional research with PDs of very short tenures and long tenures may yield further details about sustaining PDs in residency education to successfully train the next generation of family physicians.

In the 2020 US National Residency Matching Program, 4,313 students matched to a first-year position in one of 706 family medicine residencies.1 Family medicine residents learn to provide comprehensive, coordinated, first-contact, continuous care in the context of family and community.2 The training of every one of these new physicians will be overseen by a family medicine residency program director (PD).

A family medicine PD balances multiple roles as a clinician, scholar, teacher, administrator, and supervisor. PDs assure their residency program meets Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requirements and their graduates meet American Board of Family Medicine standards to become diplomates. PDs report stressors including administrative duties, clinical load, family obligations, teaching responsibilities, and research demands.3-5 Because of the extensive expectations for PDs, ACGME citations for program directors not meeting responsibilities are among the most common citations programs receive.4

Many PDs do not stay long in their positions and PD short life span may be a factor in program quality.3,6 Annually, between 11% and 14% of programs in all specialties have at least one PD change.7 In family medicine, the median PD time in their position, or tenure, is 4.5 years (mean 6.5 years).8 A recent study showed 30.5% of family medicine PDs have been in their position 0, 1, or 2 years.8 Surveys of PDs find that many PDs plan to step down in the next 1 to 2 years.6,9 The factors relating to PD departure from their positions and short program director tenure are not well known. While burnout may be a factor, and one-quarter of US PDs report burnout or depressive symptoms,10 there have been no definitive studies analyzing the relationship between well-being and the duration a family medicine PD stays in the position.9,11,12 To date, there has been no published study describing the reasons PDs leave their positions, especially those with shorter tenures. The purpose of this study was to analyze and describe factors related to program director departure from their positions.

In 2018, the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors (AFMRD) engaged the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) National Research Network (NRN) to conduct an exploratory study using in-depth interviews with PDs who recently stepped away from their PD position. The interviews included semistructured and structured questions about their experience and the process of stepping away from the PD role. The AAFP Institutional Review Board approved this study. Interviews were conducted from June 2019 to January 2020, before US residencies were altered by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data Collection

The AFMRD tracks US-based family medicine residency programs, including when directors step down from a PD position. For PDs who had left their position within the past 3 months, AMFRD staff sent a brief study description and invitation. Eighty-five departing program directors were initially contacted; 35 (41%) women and 51 (59%) men. For comparison, as of October 2020, of 593 PD members of AFMRD, 246 (42%) are women and 325 (55%) are men.13 We obtained gender and duration in current PD position from each departing program director. We did not gather other demographic data. Names of interested PDs were forwarded to the AAFP NRN staff to confirm interest and schedule a 1-hour telephone or web conference interview. We sent participants a study information sheet to review prior to the interview and encouraged them to ask questions about the study before the interview and decline participation if desired.

The initial recruitment plan called for 20 interviews. However, because the initial respondents were predominantly male with tenures longer than the median of 4.5 years, recruiting was extended to an additional five PDs in an attempt to reach female respondents or PDs with tenures less than 5 years. Although few new conceptual categories emerged from preliminary analysis, additional interviews offered the opportunity to approach conceptual saturation and achieve more representative participation.

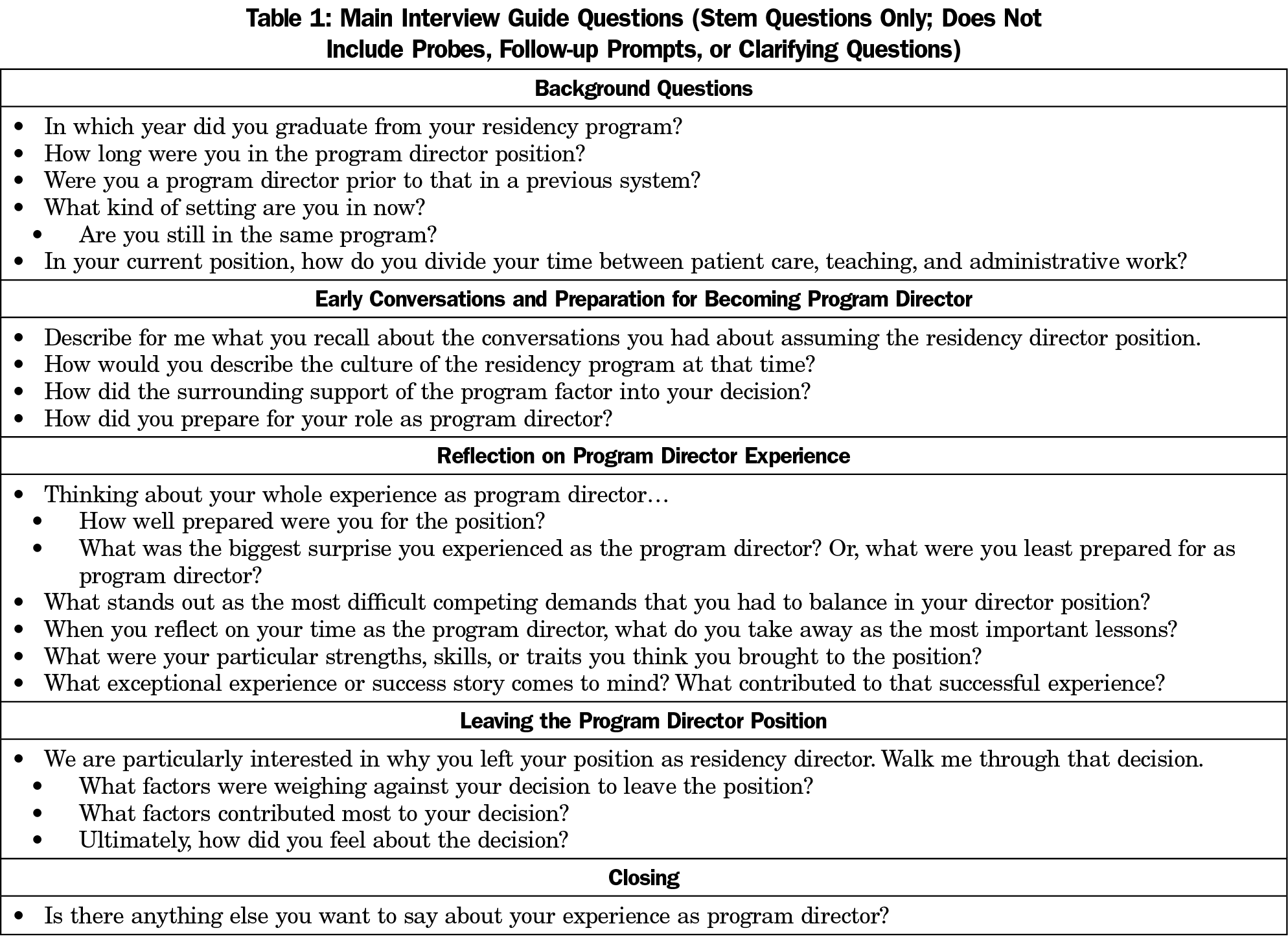

The interviews included structured and in depth semistructured questions based on the sparse existing literature, author experience as a PD (S.B.), and input from previous family medicine PDs not included in the study. The questions (Table 1) asked about the circumstances and decisions around stepping into the PD role, the climate and surrounding support of the program, how respondents prepared, what the most difficult competing demands were and the help they needed, and the circumstances and decisions around stepping away from the PD role.

Embedded structured questions asked about the PDs’ sense of accomplishments while in the PD role, sense of positive influence on other people’s lives, and level of agreement with six statements regarding challenging aspects of the PD job (such as, ability to innovate, room for other pursuits, and financial support). We recorded structured question answers on a Likert-type scale. A single study team member (D.F.) conducted interviews. We audio recorded interviews when permitted by the respondent, generating transcripts for analysis using ATLAS.ti data analysis software (version 8, Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany).

Data Analysis

Quantitative data analysis of structured interview questions included descriptive statistics and tests of association to summarize structured question data and to make general comparisons between shorter- and longer-tenure PDs, as well as other PD characteristics. We analyzed individual survey items and summative scores with Fisher Exact Test.

Qualitative data analysis of semistructured questions proceeded through several iterations, beginning with memo forms created by the interviewer (D.F.) following each interview and shared with study coinvestigators.14 Memos reflected responses to key research questions, early interpretations, and commentary about the interview in the context of other interviews, including emergent questions for follow-up interviews.

The primary analyst (D.F.) used a coding template from a priori codes to segment data into broad conceptual categories.15 The conceptual categories aligned with high-level interview guide domains to answer overall research questions and to facilitate focused analysis with subsequent inductive coding. We performed inductive coding by reviewing segmented data without a preconceived coding scheme, allowing new interpretive codes to emerge from the data itself. We repeated cycles of inductive coding across all cases until all data had been coded within the high-level domains. Documents that were coded inductively early in the analysis required multiple cycles of review to ensure new inductive codes from later interviews were not missed. We shared all inductive codes and their links to higher-level domains with coinvestigators for review, comment, and questioning.

We then developed case-based, ordered matrices to help with interpretation.14 For each case, matrices summarized the key findings, themes within conceptual domains, and brief quotations. We ordered matrices by PD tenure length. For further comparisons, we divided cases into two groups based on the median PD tenure of our sample: tenures of 6 or fewer years and tenures of more than 6 years.

Among 25 respondents, six were female (24%) and 19 (76%) were male, with an average tenure of 8.65 years (median of 6 years) and a range from 3 years to 22 years. We observed few meaningful differences in the study data among PDs with shorter or longer tenures.

Quantitative Data

Accomplishments. Twenty-two of 25 (88%) PDs felt that they frequently (a few times a week or everyday) “accomplished worthwhile things” and 23 of 25 (92%) PDs felt they “had a positive influence on other people’s lives” during their tenure. No significant differences were found between respondents with 6 years or less (shorter) and tenures of more than 6 years (longer) on how often PDs felt they “positively influenced other people lives” or “accomplished worthwhile things” while in the PD role (P=.695 and P=.645, respectively). Additionally, there were no significant differences by gender or whether the respondent stayed in the same program after stepping away from the PD role (P values >.562).

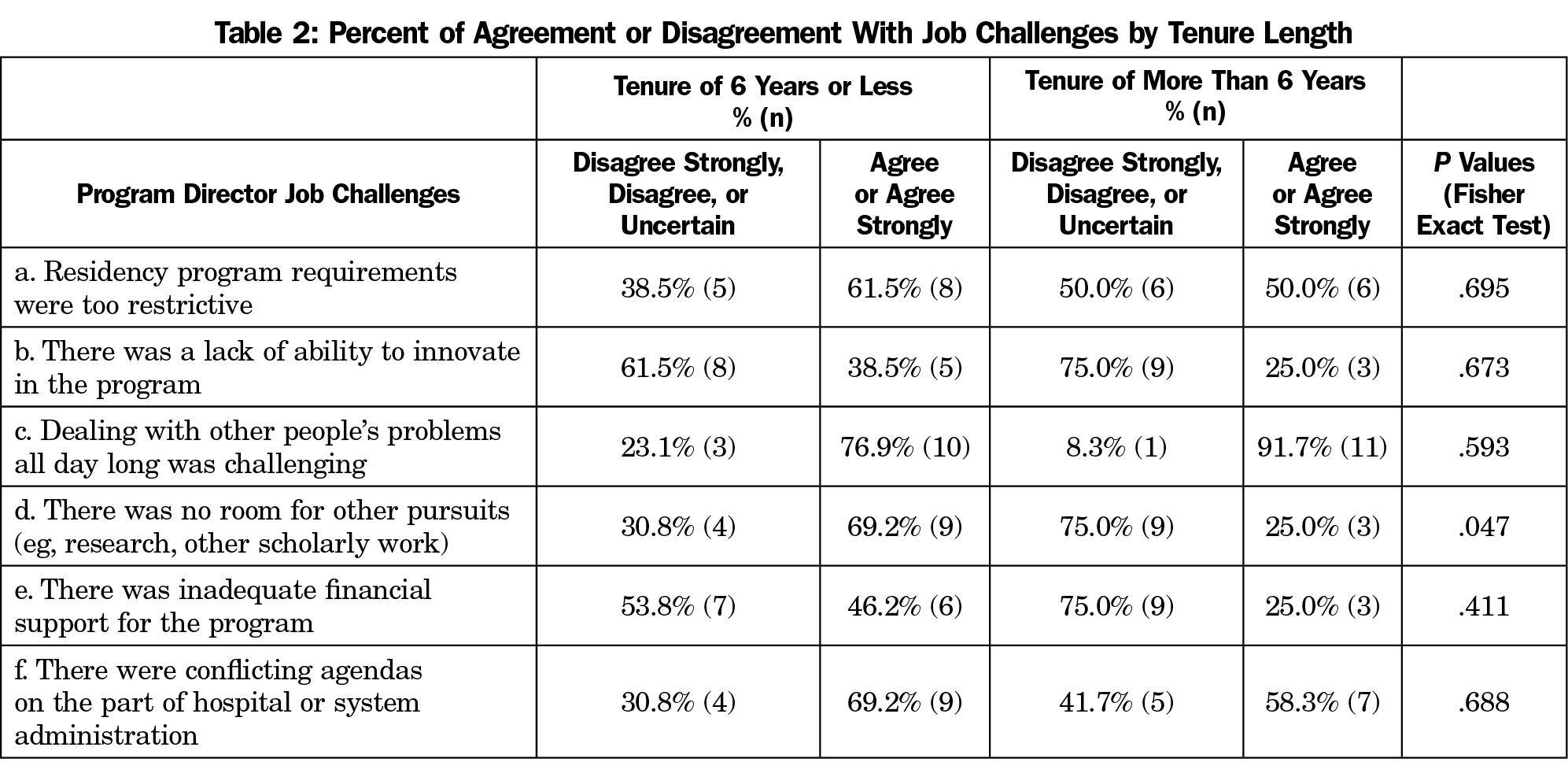

Challenges. Respondents were divided in their level of agreement about aspects of their residency program that made the PD job challenging (Table 2); however, 21 of 25 (84%) respondents, regardless of length of tenure, somewhat or strongly agreed that “having to deal with other people’s problems all day long was challenging.” The only significant difference was those with tenures of 6 years or less were more likely to agree or strongly agree that “There was no room for other pursuits” (P=.047). There were no significant differences by gender of respondent or whether the respondent stayed in the same program after departing their PD role (not shown; P values >.081).

Qualitative Data

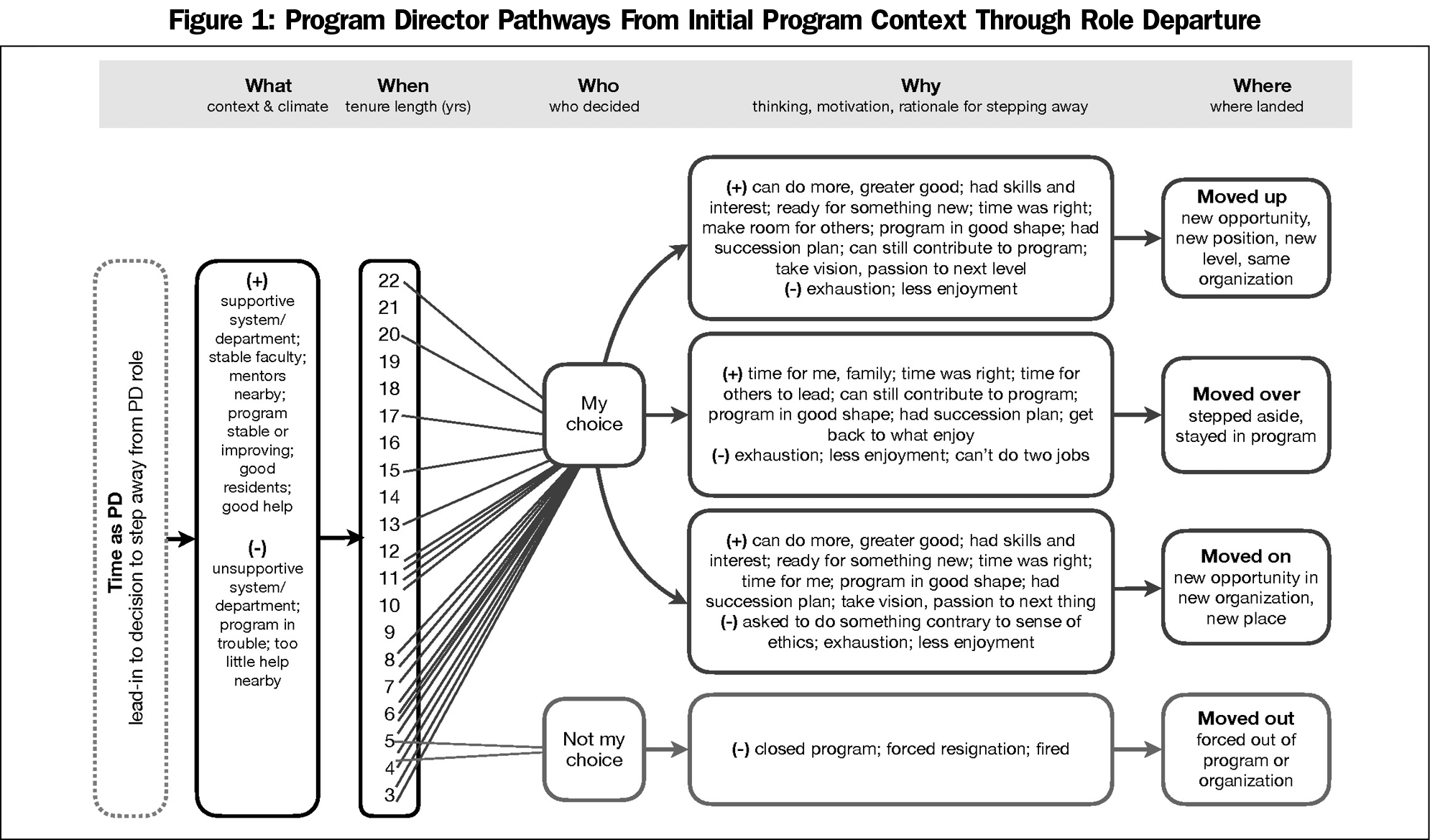

Program Director Pathways. There were few notable differences between PDs with tenures of 6 years or less and those with tenures of more than 6 years. The two groups of PDs were distinguished more by their similarities than their differences. The results below reflect overall findings from the study, noting only exceptional differences based on tenure length. The analysis revealed several pathways (Figure 1) for the departure of PDs, most of which reflect their choice to step away from the position—based on a combination of factors—in pursuit of new opportunities for themselves or others:

- Moved up to new positions and new opportunities in the same organization;

- Moved over by stepping aside to give new leaders the opportunity to step into leadership roles while they stayed in the organization to help;

- Moved on to pursue new opportunities in new organizations; and

- Moved out because they were forced out of the program or organization.

About two-thirds of PDs moved up within the same institution (eg, designated institutional official, dean, department chair) or moved over and stayed on in other roles in the program (eg, core faculty, medical director). About one-third of PDs moved on to opportunities outside of the specific programs they left and no longer maintained a presence in the program. Two PDs were forced to move out. In one case, the sponsoring institution closed a troubled program; in the other case, a new health system assumed control of the residency practice and wanted all new leadership.

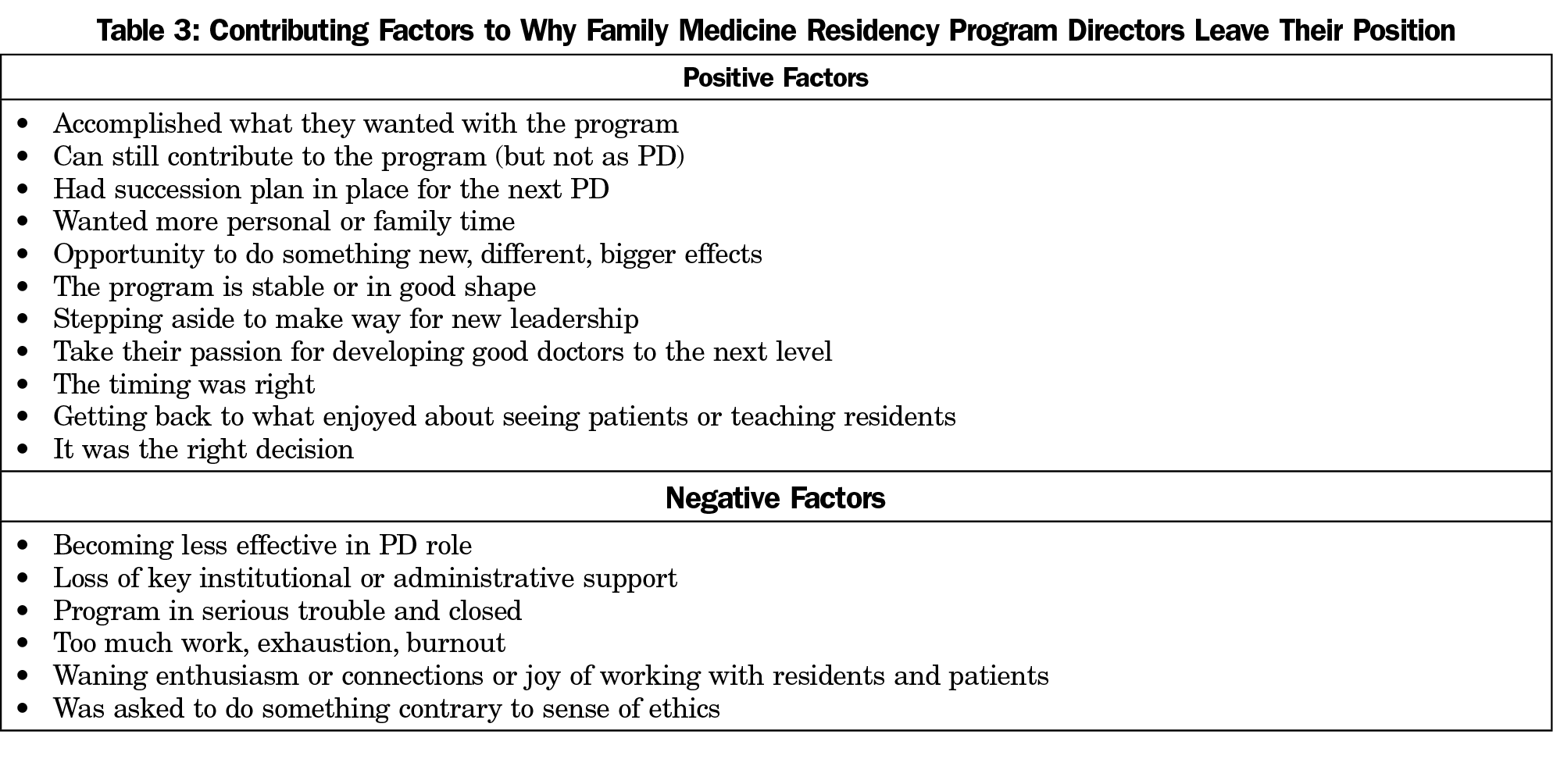

Why Do PDs Leave? PDs described combinations of factors—mostly positive—that contributed to the circumstances and decisions to step away from their role as PDs (Table 3). The main contributing factors were shared across those with shorter and longer tenures.

In our sample, most PDs, regardless of tenure length, stepped away because they had other things they wanted to do and not because of dissatisfaction with the job.

I felt like I had accomplished things. I felt like I wanted more time to travel. I felt like the program was probably gonna benefit more from new leadership than for me to stay on. I felt like I had done what I could with the program. I think every once in a while, it’s good for a program to have a shot in the arm of new leadership. (Tenure >6 years, male)

I would really like to infuse some of our [family medicine] approach into the other residencies. I want to build programs that develop doctors who are rigorously trained and also human…. (Tenure ≤6 years, female)

Factors that weighed against or delayed their decisions to step away reflected strong emotional connections to the people in the program, particularly the residents, and obligations to make sure the program was ready for a transition. When there was a clear succession plan and the outgoing PDs felt the program was in good shape, the decision of the timing of their departure was easier.

I had spent the last few years, grooming the person who would take over this role. I had slowly been introducing them to different parts of the residency and giving them different leadership opportunities.… That also made my decision [to step down] very simple…that I could take them and not leave the program in a bad box, because I would never have done that. (Tenure ≤6 years, female)

I love the residents. I just do, even though they drive me crazy. Graduation’s just the best day of the year, not because they’re leaving, because you see what they’ve become. I think it was really the residents. I think that was the hardest—the part that was weighing on me. (Tenure ≤6 years, female)

About one-third of the PDs described building exhaustion, burnout, or the burden of too much work as a factor—but not the only factor—in their decision to step away. This was more pronounced among PDs with tenures of 6 or fewer years.

What really pushed me over was just global burnout in my personal life and my professional life, just complete inability to complete anything. (Tenure ≤6 years, female)

Only those with longer tenures spoke about a strong sense that “it’s time” and they were ready for someone else to take on the PD role for their program. More PDs with longer tenures also spoke about the need for new leadership to prevent the program from stagnating and that their enthusiasm for the job was waning or their connections to residents or patients were diminishing.

…I felt like, ‘Boy, this job – this requires so much time and energy, effort, that it’s getting harder to do it.’ It was harder to do it at 60 than at 55. I appreciated that I needed to morph the job in order to make it more viable long-term for my successor, but it seemed like…maybe this is time for me to retire. (Tenure >6 years, male)

Now I was spending most of my time [as PD], or needing most of my time, to work on personnel issues rather than curriculum, teaching, advocacy work, finances—the things that actually had brought me enjoyment to the job historically. (Tenure >6 years, male)

I thought the program could use some fresh ideas and fresh leadership. I didn’t mind stepping down and allowing that to happen. (Tenure >6 years, male)

Actually, the thing for me that kind of tipped it was that I had always really enjoyed the recruiting process. That started to get boring, or mundane. (Tenure >6 years, male)

While 23 of the 25 PDs chose to move on, move up, or move over, two were forced to move out of the PD role because of significant program changes and loss of institutional support. One PD with 6 years or less tenure was forced to resign when the sponsoring institution chose to close the program after losing confidence in program viability. Another PD was abruptly fired (after 6 years or less as PD) without a reason, following the takeover of the program clinic by a new organization. In both cases, these PDs had planned to stay in their roles as PD longer.

What Sustaining Factors Are Important? PDs departing their positions often reflected on the positive factors that made the job enjoyable. They described substantial joy and rewards of the position: helping a struggling resident through to graduation, developing a collaborative program culture, or seeing the fruits of labor borne each year with graduating residents. PDs also described the importance of a strong collaborative team of faculty colleagues, program coordinators, associate program directors, and staff who help shoulder the burdens of the role. Mentors (especially those nearby) and other PDs—locally, regionally, or nationally—provide additional sustaining support.

[R]unning a residency really does have to be a team job. It can’t just be a one-person show…. I think you need a good, strong associate director. I think you need a really good, strong program coordinator. Then you need faculty with enough experience within the program that they can take on other administrative-type roles, too; not just precepting, not just giving lectures, but really taking ownership of parts of the program and being able to administrate them. (Tenure >6 years, male)

Do Initial Program Conditions and Preparation Matter? When PDs in our sample stepped into the role, they felt that they could contribute to building or rebuilding the program and that they were the best person for the role. The conditions in the residency program and surrounding institution were described variably, from challenging and unstable programs with little institutional support to strong and stable programs with good institutional support. The initial climate and conditions of the programs did not seem to be a factor in the length of tenure. For several PDs with longer tenures, the fact that their program was in trouble was part of their reason for taking on the PD role initially; if the program was to survive, it was up to them.

A number of people left. Several were planning on leaving. It got to where [the previous PD] was asked to leave by the hospital administration. I’m completely different personality-wise and felt that I knew what the problems were and was different enough that I could correct things. I felt like it was an opportunity for me to make a difference, so I jumped in. (Tenure >6 years, male)

…the family medicine program was changing sponsoring institutions because the hospital that was sponsoring it was being sold…. At the same time, the guy who was the program director was leaving for unrelated reasons. I was the associate director at the time, and they said, “Will you be the director?” and that’s how that happened…. Somebody had to do it. (Tenure >6 years, male)

Most PDs felt as well prepared as they could have been. Most had completed a formal leadership training course, the National Institute for Program Director Development (NIPDD). As one PD quipped, “I was prepared as well as I could be, and not nearly enough.” There is necessary on-the-job learning regardless of formal training. Two PDs with longer tenure and two with shorter tenure believed they were not well prepared for the PD role; however, even those with shorter tenures stayed in the PD role between 5 and 6 years.

I think I was pretty well prepared because I had been a community faculty member practicing in a small town but working with residents nearly every day for 8 years and then a core faculty member in a community program for 11 years. I think, to the extent that anybody is ready to be program director, I feel like I was prepared as anybody could be. (Tenure >6 years, male)

I think I was as well prepared as I could be. When I look back, I think there’s just a lot of things you don’t know until you live it. (Tenure ≤6 years, female)

Ours is the first study describing reasons why family medicine residency PDs leave their positions. Although PDs in our study described differing pathways during their tenures, there were few differences in why PDs left the position when we compared cases with longer and shorter tenures. Multiple factors contributed to their decisions to step away from the PD role. The vast majority (92%) left voluntarily. Most PDs left for positive reasons with a commitment to doing more good in the field of medicine or letting new people step in to lead. In a few cases, institutional factors put PDs at risk even when they wanted to stay on longer. Succession planning was an important part of PD transitions regardless of PD tenure length and helped make the decision easier to move over for others to lead as PDs.

Our study contributes to the understanding of why some PDs leave their positions. Because physician turnover is expensive16,17 and PD turnover may be associated with poorer residency program quality,3,6 there is continuing interest in sustaining PDs in their positions longer. Previous research suggests that formal PD training may help lengthen PD tenure18,19; however, in our sample, self-described levels of preparedness did not appear to be a distinguishing factor in tenure length. Departing PDs in our study felt as prepared as they could be for their position, and formal training played some role with three-quarters having attended NIPDD.

A 1996 survey study of PD turnover in internal medicine residencies found factors associated with turnover included low satisfaction with colleague relationships, high percentage of administrative work, perceiving the job as a stepping stone, and having had formal training to deal with problem residents.12 None of these findings emerged as major themes in our qualitative study of family medicine PDs departing their positions.

Attention to building and sustaining a good team may be important for lengthening PD tenure, as effective team-based care and teams have been associated with known benefits to staff and clinicians (including reduced burnout).20,21 We found that helping PDs build collaborative teams may help improve satisfaction and share the workload, including administrative tasks others can do. However, our data suggest these factors alone will be insufficient to help reduce turnover of PDs with shorter tenure.

Greater attention is being given to clinician well-being,22 with special focus on clinician burnout (including among PDs).11,18,23,24 Previous literature is equivocal on the role burnout plays in PD turnover. A 2019 survey of internal medicine PDs found 33% met criteria for burnout, and 85% of those that met criteria for burnout had considered resigning.25 Results of a 2018 survey of family medicine PDs found no association between program tenure and symptoms of burnout, with rates of burnout comparable to other physicians.11 The PDs we surveyed almost universally found meaning in their work, as indicated by having a positive influence on other people’s lives (92%) and accomplishing worthwhile things (88%), which is a protective factor against burnout.26 While several PDs in our study described building exhaustion and burnout as contributing factors, these were not the only factors. Given our finding that exhaustion or the perception of too much work was more of a factor for PDs with shorter tenure, additional support for these PDs may be beneficial. Our findings suggest addressing physician burnout may not contribute meaningfully to lengthening PD tenure.

Additionally, it may be worth emphasizing the benefits that can come with the position and helping new PDs acknowledge those benefits.27 In our small sample, about 90% felt that they accomplished worthwhile things or positively influenced other people’s lives a few times a week or every day. There may be other important factors that help to sustain PDs that we did not formally ask about. Further study on PD joys and rewards, especially for those who stay longer in their position, may further our understanding of factors related to PD tenure. We did not gather data about departing program director race or ethnicity. As family medicine leaders from backgrounds underrepresented in medicine face unique challenges, this is an important area of further study.28

Limitations

With this small, nonrandom sample of respondents, we cannot draw conclusions about the larger population of family medicine residency PDs who left their positions during the study period. One interviewer conducted all interviews, which could be a source of bias; however, a single experienced interviewer using semistructured and structured questions provides consistency of elicitation across respondents. While there was consistency across respondents in our sample, there may be additional substantive reasons why PDs leave their roles, which may suggest additional support strategies for retaining PDs. Because our sample included no respondents with fewer than 3 years of tenure, there remains an important gap in knowledge about turnover among PDs who are in the role for very short tenures and who account for the highest frequencies of PDs who step down.8 A census of all departing family medicine PDs, with a survey informed by the findings of our study, could help address the limitations of our study and provide additional information on PDs who stay in their position for fewer than 3 years. Furthermore, assessing why long-tenured PDs stay in their positions may help understand what might help sustain PDs in the role and could provide information about factors important for early retention.

The program director is an essential component for success in ACGME residencies. This study has important implications for retaining PDs while highlighting the importance of programs being prepared for potential change to support excellence in residency education to train the next generation of family physicians.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank AAFP NRN staff member Kaari Van Auken and AFMRD staff members Sam Pener, Deanne St George, and Chris Pyle.

Financial support: Funding was provided by the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors. The funder assisted with initiating participant recruitment but had no further role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data, or in the writing of the manuscript. At the time of the study and manuscript preparation, Dr Brown was President-Elect and President of the Board of Directors of the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors. He received no compensation as a coauthor of this study.

Prior presentations: This study was presented at the North American Primary Care Research Group Annual Meeting (virtual), November 20-24, 2020.

References

- American Academy of Family Physicians. 2020 Match Results for Family Medicine. https://www.aafp.org/medical-school-residency/program-directors/nrmp.html. Published 2020. Accessed May 18,2020.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. https://www.acgme.org/Specialties/Program-Requirements-and-FAQs-and-Applications/pfcatid/8/Family%20Medicine. Accessed March 16, 2021.

- Barton LL, Friedman AD. Stress and the residency program director. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1994;148(1):101-103. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1994.02170010103024

- Lypson M, Simpson D. It all starts and ends with the program director. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):261-263. doi:10.4300/JGME-03-02-33

- West CP, Halvorsen AJ, Swenson SL, McDonald FS. Burnout and distress among internal medicine program directors: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(8):1056-1063. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2349-9

- Mitchell K, Maxwell L, Bhuyan N, et al. Program director turnover. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(5):482-483. doi:10.1370/afm.1703

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Data Resource Book Academic Year 2018-2019. Chicago: ACGME; 2019.

- Brown SR, Gerkin R. Family Medicine Program Director Tenure: 2011 Through 2017. Fam Med. 2019;51(4):344-347. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.730498

- De Oliveira GS Jr, Almeida MD, Ahmad S, Fitzgerald PC, McCarthy RJ. Anesthesiology residency program director burnout. J Clin Anesth. 2011;23(3):176-182. doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2011.02.001

- Psenka TM, Freedy JR, Mims LD, et al. A cross-sectional study of United States family medicine residency programme director burnout: implications for mitigation efforts and future research. Fam Pract. 2020;37(6):772-778. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmaa075

- Porter M, Hagan H, Klassen R, Yang Y, Seehusen DA, Carek PJ. Burnout and Resiliency Among Family Medicine Program Directors. Fam Med. 2018;50(2):106-112. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.836595

- Beasley BW, Kern DE, Kolodner K. Job turnover and its correlates among residency program directors in internal medicine: a three-year cohort study. Acad Med. 2001;76(11):1127-1135. doi:10.1097/00001888-200111000-00017

- Weidner A, Clements D. Council of Academic Family Medicine Leadership Demographics. Ann Fam Med. In press.

14 Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative data analysis : a methods sourcebook. Third edition. ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2014.

- Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications; 1999.

- Hamidi MS, Bohman B, Sandborg C, et al. Estimating institutional physician turnover attributable to self-reported burnout and associated financial burden: a case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):851. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3663-z

- Han S, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(11):784-790. doi:10.7326/M18-1422

- Pugno PA, Dornfest FD, Kahn NB Jr, Avant R. The National Institute for Program Director Development: a school for program directors. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15(3):209-213.

- Palmer EJ, Tippy PK, Bope ET, et al. National Institute for Program Director Development (NIPDD): a collaborative pursuit of excellence. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):374-375. doi:10.1370/afm.877

- Helfrich CD, Dolan ED, Simonetti J, et al. Elements of team-based care in a patient-centered medical home are associated with lower burnout among VA primary care employees. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(S2)(suppl 2):S659-S666. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2702-z

- Rosen MA, DiazGranados D, Dietz AS, et al. Teamwork in healthcare: key discoveries enabling safer, high-quality care. Am Psychol. 2018;73(4):433-450. doi:10.1037/amp0000298

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-576. doi:10.1370/afm.1713

- Smith CD, Balatbat C, Corbridge S, et al. Implementing optimal team-based care to reduce clinician burnout. mplementing optimal team-based care to reduce clinician burnout. NAM Perspectives.Discussion Paper. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine; September 17, 2018. doi:10.31478/201809c

- Helfrich CD, Dolan ED, Simonetti J, et al. Elements of team-based care in a patient-centered medical home are associated with lower burnout among VA primary care employees. J Gen Intern Med2014;29 Suppl 2(S2):S659-66.

- O’Connor AB, Halvorsen AJ, Cmar JM, et al. Internal medicine residency program director burnout and program director turnover: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2019;132(2):252-261. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.10.020

- Hooker SA, Post RE, Sherman MD. Awareness of meaning in life is protective against burnout among family physicians: a CERA study. Fam Med. 2020;52(1):11-16. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.562297

- Kendall MC. Burnout in program directors: we still need more answers. Fam Med. 2018;50(6):481. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.755139

- Foster KE, Johnson CN, Carvajal DN, et al. Dear white people. Ann Fam Med. 2021;19(1):66-69. doi:10.1370/afm.2634

There are no comments for this article.