Background and Objectives: Among the oldest in the nation, the University of Utah Physician Assistant Program (UPAP) serves the state of Utah and surrounding areas and is a division of the Department of Family and Preventive Medicine. Recognizing the need to produce health care providers from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds, UPAP instituted structural changes to improve student compositional diversity. This paper is a presentation and evaluation of the changes made to determine their relationship with compositional diversity, ultimate practice setting, and national rankings.

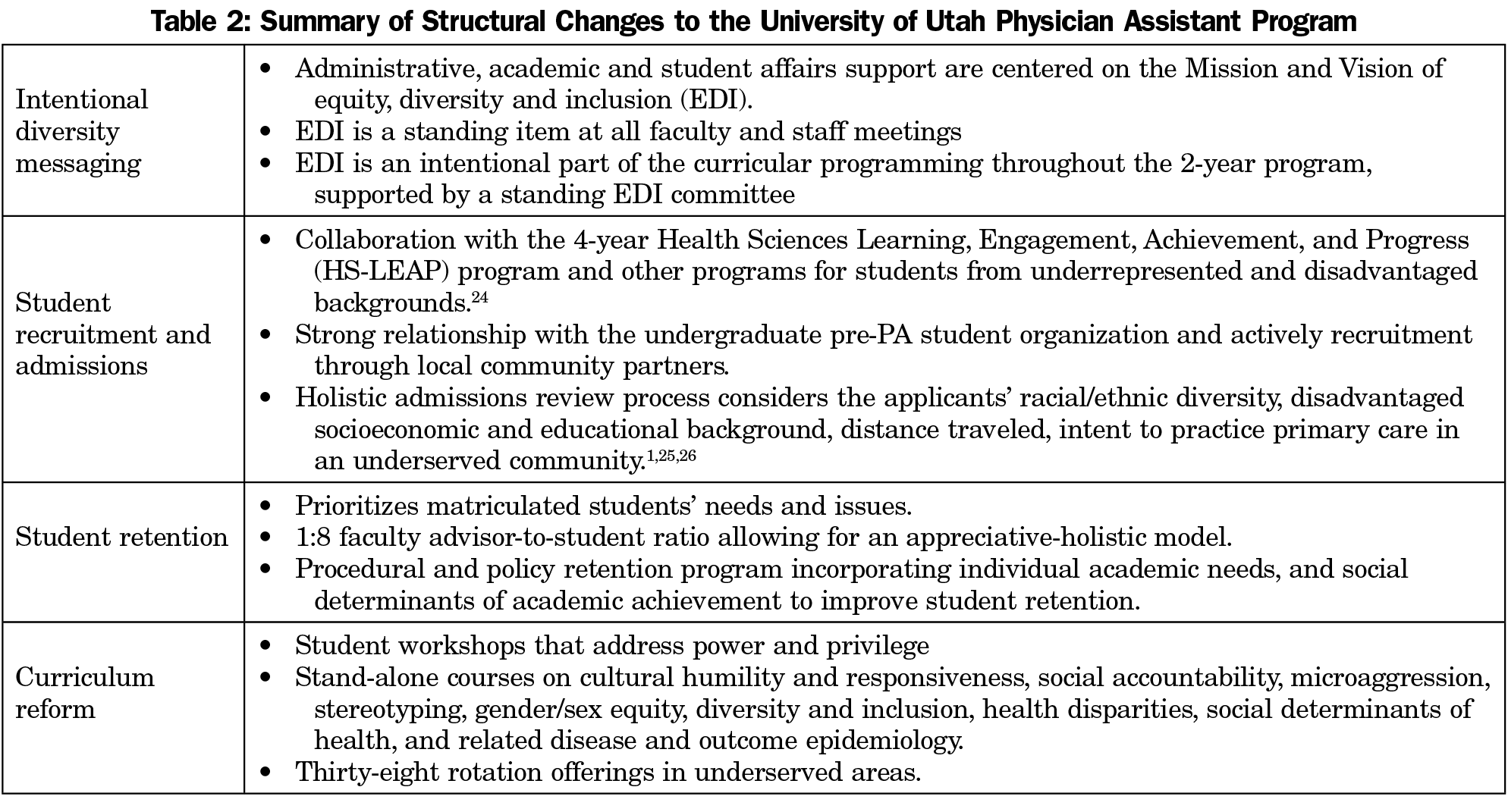

Methods: UPAP changed diversity messaging, curriculum, efforts in admissions, recruitment, and retention to improve the representation of Black, Latinx, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander students, as well as those from educationally and economically disadvantaged backgrounds.

Results: UPAP tripled the number of underrepresented minority matriculated students over the course of five admitted classes, while simultaneously increasing the proportion of students from educationally or economically disadvantaged backgrounds. UPAP maintains both high boards pass rate and top national rankings, (number two ranking in public physician assistant program and number four overall program in the United States).

Conclusions: The UPAP experience demonstrates that intentional diversity efforts are associated with improvement in racial/ethnic diversity and national rankings. Other medical school graduate programs, specifically the medical doctor (MD), public health, and basic science programs can use this model to improve their compositional diversity.

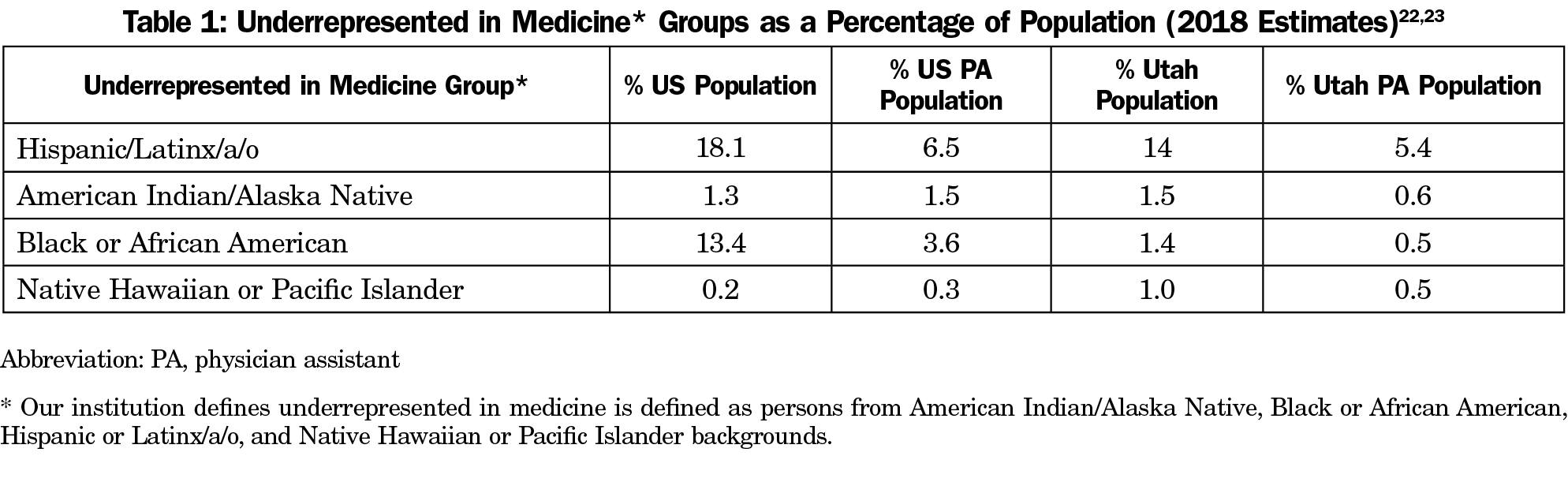

A racially and ethnically diverse health workforce is critical to all communities in the United States, especially those that are underserved.1,2 US Census data show that groups collectively known as underrepresented in medicine (URM) are growing at rates much higher than the US White population.3,4 The US physician assistant (PA) profession, however, does not mirror the current population,5,6 and has recently experienced an increase in White matriculants.7 As a result, while URM populations in the United States are increasing, the PA workforce remains predominantly White. Similarly, the diversity of the Utah PA workforce lags behind the Utah population (Table 1).8

A health care workforce that mirrors the diversity of the population can help reduce health disparities.9,10 Because PAs care for increasingly diverse populations with complex needs, the PA workforce must change.11 Recognizing the need to diversify the PA workforce, the University of Utah Physician Assistant Program (UPAP) underwent a radical transformation over the last decade through intentional changes in admissions, student support, and curriculum. This study examined the equity, diversity, and inclusion changes implemented by UPAP and compares outcomes over a 5-year period. As about 20% of PAs practice in primary care settings, increasing diversity in PA programs can increase the diversity of the primary care workforce. In addition, UPAP techniques presented in this manuscript can be implemented in medical school admissions as well as family medicine resident selection.

UPAP initiated changes to foster and encourage equity, diversity, and inclusion in the program over the last decade. UPAP focused on four broad areas: intentional diversity messaging, student recruitment and admissions, student retention, and curriculum reform (Table 2).

Measuring the Impact

To measure the impact of these equity, diversity, and inclusion changes from 2014 to 2019, UPAP compared matriculated students’ admissions application data, including race/ethnicity/gender demographics and students’ self-identified educationally or environmentally disadvantaged status. Upon each cohort’s graduation, UPAP used the graduates’ National Provider Identifier (NPI) numbers to track employment location and practice specialty, focusing on medically underserved communities (MUC). UPAP followed the annual US News and World Report program ranking to correlate the program ranking with practice setting and student diversity. UPAP assessed preparedness for practice with the Physician Assistant National Certifying Exam (PANCE). The University of Utah Institutional Review Board deemed this project exempt from review.

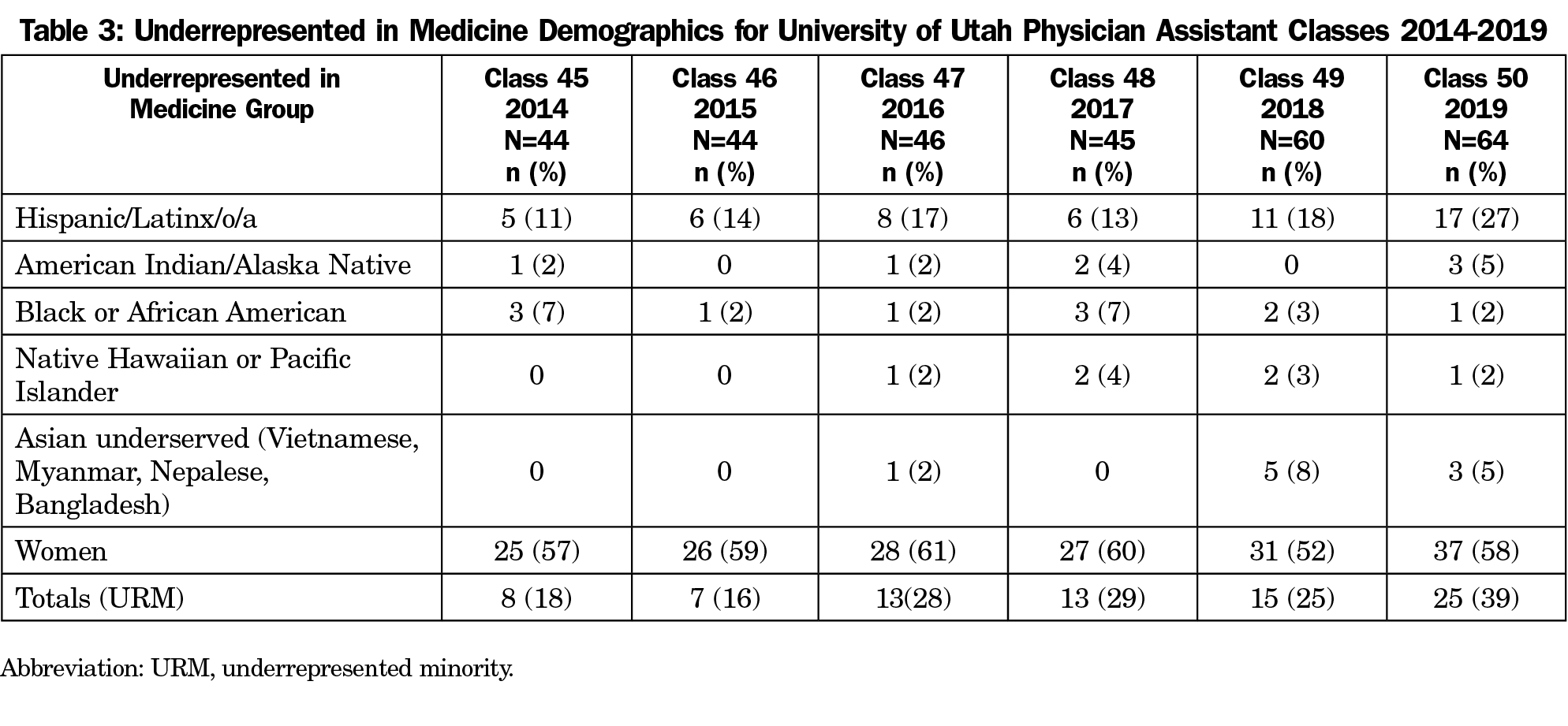

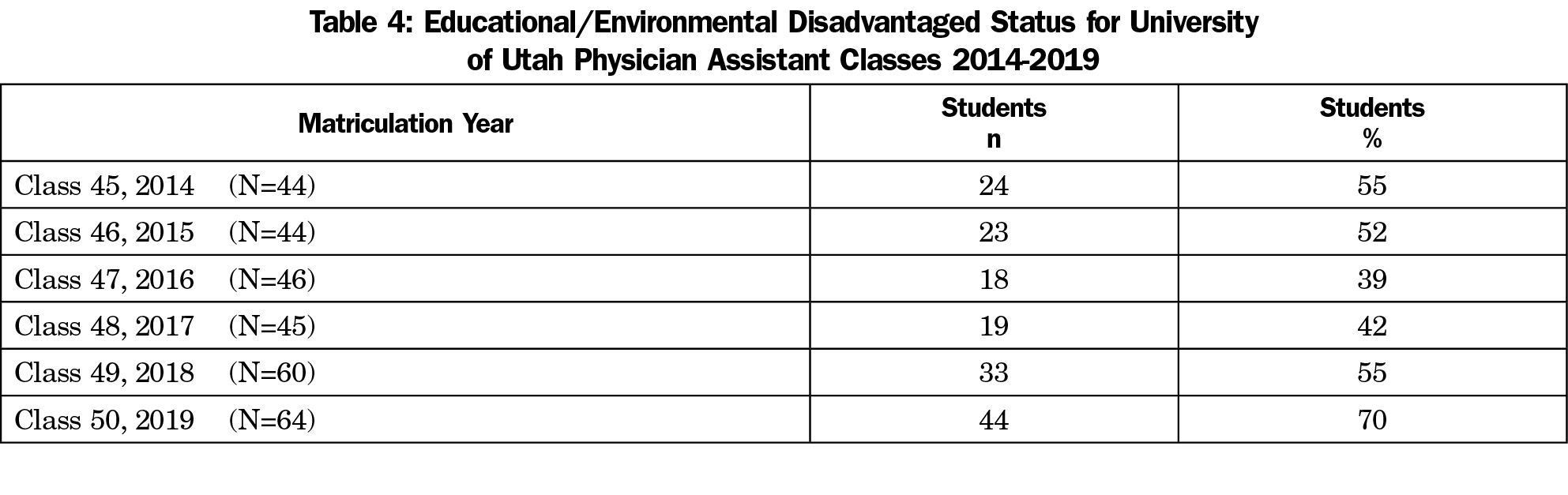

In almost all categories, UPAP matriculated more URM students each year from 2014 to the entering class of 2019 (Table 3). The class size increased by 45%, from 44 to 64. At the same time, URM matriculated students increased by 212% from 8 to 25 per class (18% to 39% of students). Women in the class remained relatively constant between 52% and 61%. Students who self-identified with educational or environmental disadvantaged status increased over the observation period from 24 to 44 (55% to 70% of students; Table 4).

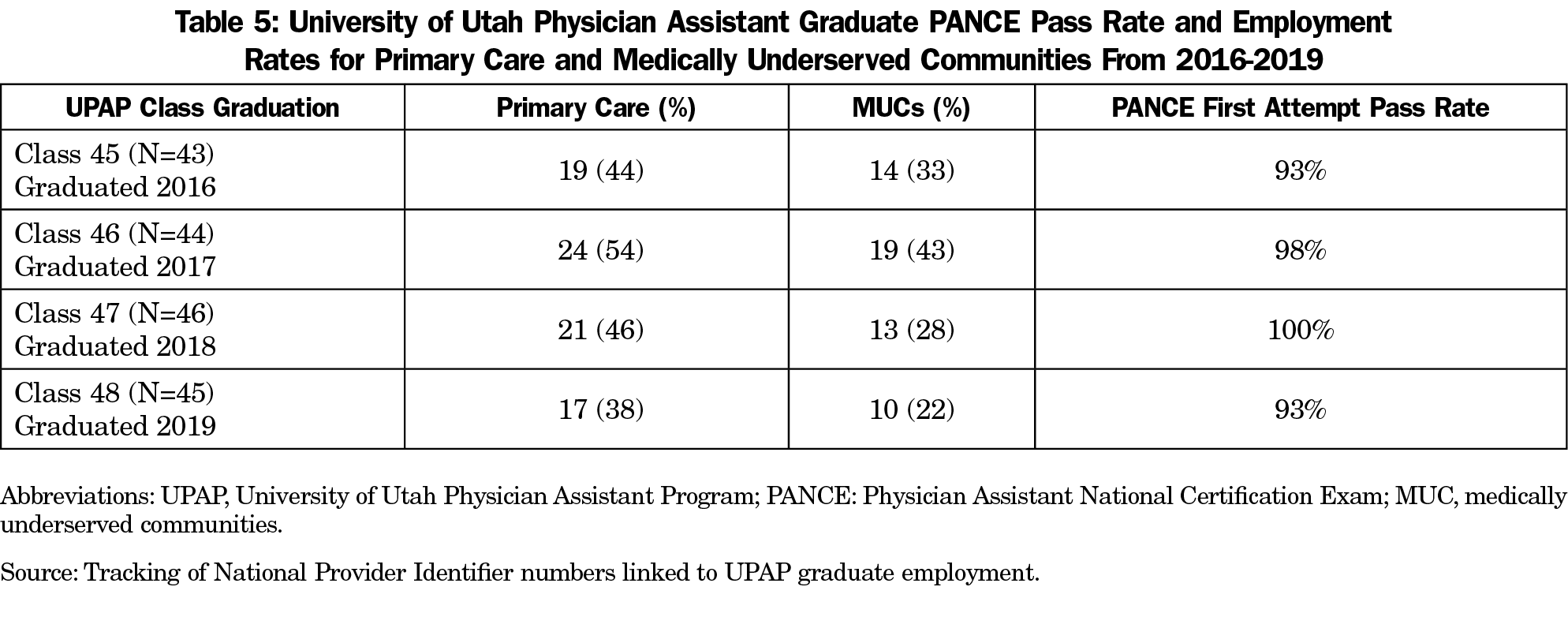

For the four classes that graduated during the study period, employment in primary care settings was high across all years, varying from 38% to 54%, as did employment in medically underserved communities (MUC), varying from 22% to 43% (Table 5). First-time PANCE pass rates varied over the observation period from 93% to 100%; all graduates passed the PANCE by the second attempt. UPAP’s ranking by US News and World Report improved from number five in 2015-201612 to number four in 2019-2020.13

With an intentional focus on increasing diversity, UPAP tripled the number of URM matriculated students over the course of five admitted classes, while simultaneously increasing the proportion of students from educationally or economically disadvantaged backgrounds. At the same time, UPAP’s class size increased to meet the UPAP-mission-based medical workforce needs. Utilizing holistic admissions criteria increased the diversity of UPAP’s matriculating class.14 UPAP’s initiatives have resulted in a diverse class, an increase in national rankings, and a stable high percentage first-attempt PANCE pass rate.

The matriculated UPAP students in 2019-2020 are now as diverse as Utah’s general population, allowing for improved racial and ethnic concordance with providers and patients.15 Provider-patient concordance improves communication, trust, and patient satisfaction.16-19 Twenty percent of UPAP graduates practice in underserved settings while the national average for new PA graduates is 7%.20 Uniquely, while White matriculation is increasing nationwide,7 UPAP increased matriculation of URM, low socioeconomic status, and educationally disadvantaged students. Furthermore, this increase in diverse matriculation is associated with an increase in national rankings of UPAP.

UPAP has been successful in, and remains committed to, a process of continuous diversity improvement to ensure that the gains of the last 5 years are built upon for the foreseeable future. UPAP must remain vigilant in selecting applicants who intend to work in primary care, in addition to continuing equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts. The successful changes from UPAP can be made elsewhere, even in areas with limited racial/ethnic diversity. Utah as a whole, as well as the UPAP faculty, are majority non-URM; UPAP prioritizes the retention and recruitment of all faculty and has made the hiring of URM faculty a priority in its strategic plan. The model may be effective for medical schools as well as PA schools, and may be easier to implement in medical schools as there are fewer students per seat soliciting admission.21 The UPAP transformation may be duplicated in family medicine residencies and assist in increasing the diversity of the family medicine workforce.

References

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Institutional and Policy-Level Strategies for Increasing the Diversity of the U.S. Healthcare Workforce. In the Nation's Compelling Interest: Ensuring Diversity in the Health-Care Workforce. Smedley BD, Stith Butler A, Bristow LR, editors. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004.

- Snyder CR, Frogner BK, Skillman SM. Facilitating Racial and Ethnic Diversity in the Health Workforce. J Allied Health. 2018;47(1):58-65.

- Frey WH. The US will become 'minority white' in 2045, census projects. The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2018/03/14/the-us-will-become-minority-white-in-2045-census-projects/. Published March 14, 2018. Accessed March 11, 2020.

- United States Census Bureau. Quick Facts: United States. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/RHI125219. Accessed September 4, 2019.

- LeLacheur S, Barnett J, Straker H. Race, ethnicity, and the physician assistant profession. JAAPA. 2015;28(10):41-45. doi:10.1097/01.JAA.0000471609.54160.44

- Yuen CX, Honda TJ. Predicting physician assistant program matriculation among diverse applicants: the influences of underrepresented minority status, age, and gender. Acad Med. 2019;94(8):1237-1243. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002717

- Physician Assistant Education Association. By the Numbers: Student Report 3: Data From the 2018 Matriculating Student and End of Program Surveys. Washington, DC: PAEA, 2019. doi: 10.17538/SR2019.0003

- Utah Medical Education Council. Utah’s Physician Assistant Workforce, 2019: A Study of the Supply and Distribution of Physician Assistants in Utah. Salt Lake City, UT: 2019. https://umec.utah.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019-PA-Report-Final-2019.10.24.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2021.

- Senf JH, Campos-Outcalt D, Kutob R. Factors related to the choice of family medicine: a reassessment and literature review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003 Nov-Dec 2003;16(6):502-12. doi:10.3122/jabfm.16.6.502

- Moy E, Bartman BA. Physician race and care of minority and medically indigent patients. JAMA. 1995;273(19):1515-1520. doi:10.1001/jama.1995.03520430051038

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. 2018 Statistical Profile of Certified Physician Assistants by State. Johns Creek, GA: NCCPA; 2019. https://prodcmsstoragesa.blob.core.windows.net/uploads/files/2018StatisticalProfileofCertifiedPhysicianAssistantsbyState.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2021.

- Wilets K. US News Ranks U of U Health Sciences Programs Among Best in the Country: Significant Jump in Nursing Rankings. University of Utah Health News and Announcements. https://healthcare.utah.edu/publicaffairs/news/2015/03/03-10-2015_nursing.honor.php. Published March 10, 2015. Accessed June 4, 2020.

- Best Physician Assistant Programs. US News and World Report. https://www.usnews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-health-schools/physician-assistant-rankings. Accessed February 2, 2021.

- Ballejos MP, Rhyne RL, Parkes J. Increasing the relative weight of noncognitive admission criteria improves underrepresented minority admission rates to medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27(2):155-162. doi:10.1080/10401334.2015.1011649

- Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers PF, Wilkerson L. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity-related outcomes in US medical schools. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1135-1145. doi:10.1001/jama.300.10.1135

- Saha S, Taggart SH, Komaromy M, Bindman AB. Do patients choose physicians of their own race? Health Aff (Millwood). 2000;19(4):76-83. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.19.4.76

- Shen MJ, Peterson EB, Costas-Muñiz R, et al. The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: a systematic review of the literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(1):117-140. doi:10.1007/s40615-017-0350-4

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(3):296-306. doi:10.2307/3090205

- Cooper LA, Beach MC, Johnson RL, Inui TS. Delving below the surface: understanding how race and ethnicity influence relationships in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(S1)(suppl 1):S21-S27. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00305.x

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Statistical Profile of Certified Physician Assistants. An Annual Report of the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. 2017;2018:21.

- McDaniel MJ, Ruback TJ. Physician assistant applicant pool: the first 50 years. J Physician Assist Educ. 2017;28(suppl 1):S18-S23. doi:10.1097/JPA.0000000000000145

- United States Census Bureau. Utah Dashboard. Population Estimates, July 1, 2019. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/dashboard/UT/PST045219. Accessed January 23, 2021

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. 2017 Statistical Profile of Certified Physician Assistants: An Annual Report of the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Johns Creek, GA: National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants; 2018. https://prodcmsstoragesa.blob.core.windows.net/uploads/files/2017StatisticalProfileofCertifiedPhysicianAssistants%206.27.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2021.

- Bliss C, Wood N, Martineau M, Hawes KB, López AM, Rodríguez JE. Exceeding expectations: students underrepresented in medicine at University of Utah Health. Fam Med. 2020;52(8):570-575. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.137698

- Fenton JJ, Fiscella K, Jerant AF, et al. Reducing medical school admissions disparities in an era of legal restrictions: adjusting for applicant socioeconomic disadvantage. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(1):22-34. doi:10.1353/hpu.2016.0013

- Ray R, Brown J. Reassessing student potential for medical school success: distance traveled, grit, and hardiness. Mil Med. 2015;180(4)(suppl):138-141. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00578

There are no comments for this article.