Background and Objectives: Family physicians are positioned to provide care for transgender patients, but few are trained in this care during residency. This study examines associations between program directors’ (PDs) perceptions/beliefs on transgender health care and inclusion of gender-affirming health care (GAH) in residency curriculum.

Methods: Questions regarding current training in GAH, provision of GAH, competency in GAH delivery, barriers to GAH training, resident desire for GAH training, access to GAH curriculum, and feelings/perceptions about GAH were included in the 2020 Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) Program Director Survey.

Results: Challenges to including GAH in residency curriculum were inadequate numbers of transgender patients for residents to provide care (35.4%) and lack of faculty expertise in GAH for transgender patients (24.6%). PDs were more likely to include GAH into curriculum when they provided care for transgender patients in their own practice, completed continuing medical education in GAH since completing residency, had confidence in teaching GAH to residents, had residents who requested training on GAH, or had access to a GAH curriculum. PDs who believed that GAH should be a core competency in residency curriculum were more likely to have residents who requested increased education in GAH and wanted to provide GAH to transgender patients in their future practices.

Conclusions: Barriers persist for training family medicine residents in GAH for transgender patients, but further training opportunities for faculty could help to decrease identified barriers. Further research should explore how best to increase family medicine faculty comfort/competence in educating residents in GAH.

Conservative estimates report 0.3% of the total US population is transgender, representing 1 million individuals.1,2 Stigma toward transgender persons is common, leading to prejudice and discrimination on structural, interpersonal, and individual levels that contribute to avoidance of health care.3,4 Reported barriers to health care access include finding a knowledgeable clinician, reluctance to disclose, structural barriers, and financial barriers.1,3,9 Some transgender patients report being refused care or being harassed in a health care setting.8 The barriers and discrimination result in many transgender patients either not seeking preventive care5,7,8,10 or postponing care.6

One of the major barriers to health care access for transgender patients is the shortage of physicians able to provide culturally competent gender-affirming health care (GAH), defined as medical and other interventions that assist in aligning a person’s physical appearance and gender identity.18,9 Transgender patients have unique health care needs that require clinicians, medical support staff, and nonmedical support staff have gender-affirming training in order to deliver care appropriately. For example, care teams need to be educated in gender-affirming language, evidence-based implementation of cancer screenings, and implementation of hormone therapy consent, prescribing, and follow up.18-21

Currently, many physicians receive no training on transgender health care in medical school or residency, and those who have, reported that it was not very or not at all useful.11 While many medical training programs have attempted to address the lack of knowledge regarding care of transgender patients within the health care community through curricula in cultural competency, this training alone is inadequate to graduate physicians knowledgeable in transgender health, including GAH.1 Barriers to implementing GAH education into medical curriculum at both the undergraduate and graduate level include a lack of trained faculty, faculty perception that transgender health care is not relevant to their practice or clinical specialty, and a lack of faculty and attending physician role models with whom students can discuss clinical issues of sexual orientation, attraction, or gender identity.10 However, evidence suggests that even small increases in education about GAH increase medical trainees’ comfort and willingness to treat transgender patients in the future.12 In one study of second-year medical students who completed a class about gender identity, classic treatment regimens, and monitoring requirements, the researchers documented a 59% reduction in students’ anticipated discomfort caring for transgender patients.12 When considering graduate medical education-specific evidence evaluating inclusion of GAH into residency education, a paucity of literature is available.15 One Canadian study of pediatric residency programs noted significant variability in education on gender diversity amongst pediatric residency programs.7 Another study showed that 71% of family medicine residents felt that GAH was within their scope of practice, but only 10% felt competent in providing GAH by the completion of residency.15 Training in GAH has expanded in family medicine residencies but still faces barriers, such as lack of knowledge and experience among faculty, belief of some physicians that providing GAH is contrary to their religious or ethical code, or beliefs that GAH is within the purview of a different medical specialty.15

Family physicians are uniquely positioned to provide GAH for transgender patients.16 Family medicine residencies, therefore, have begun and should continue, educating residents on the provision of medically comprehensive care of transgender patients. Identifying departmental values toward, and access to, curriculum on GAH in family medicine residencies can identify future directions for improving resident education. This study examines the current status of GAH training and curriculum in family medicine residency programs through the perspective of program directors.

Survey question development and data collection followed the guidelines of the 2020 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) annual survey of family medicine program directors. A comprehensive literature review and previous survey of clerkship directors guided survey question development. Each question underwent multiple iterations of revision by the research team. Family physicians who were not in the survey target group (three members of the Steering Committee and three other residency faculty) piloted the survey to evaluate its quality. We modified the questions according to feedback from the pilot to improve readability, flow, and timing.

The methodology of the CERA Program Director Survey has been previously described.23 The CERA Steering Committee evaluated questions for consistency with the overall subproject aim, readability, and existing evidence of reliability and validity.

We performed all statistical analysis using SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) and we assessed statistical significance using an a level of 0.05. We calculated descriptive statistics on all variables and included frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, means and standard deviations for continuous variables, and medians and interquartile ranges for ordinal variables. To examine the association between likelihood of including GAH into the curriculum or belief that GAH should be a core topic in the training program with various other variables, we used Spearman rank correlations. We assigned all Likert scale variables, with strongly agree as a value of 5, and strongly disagree as a value of 1, so that increasing values indicated more agreement.

The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved the project in April 2020. Data were collected from May 11, 2020 to June 2, 2020.

The survey was emailed to 660 individuals with valid contact information. The survey contained a qualifying question to remove programs without three resident classes. This filter reduced the sample size to 626 with responses from 249 PDs (39.78%). Nine of these respondents answered demographic questions, but did not answer the GAH survey questions and were excluded from this analysis, bringing the total sample size to 240.

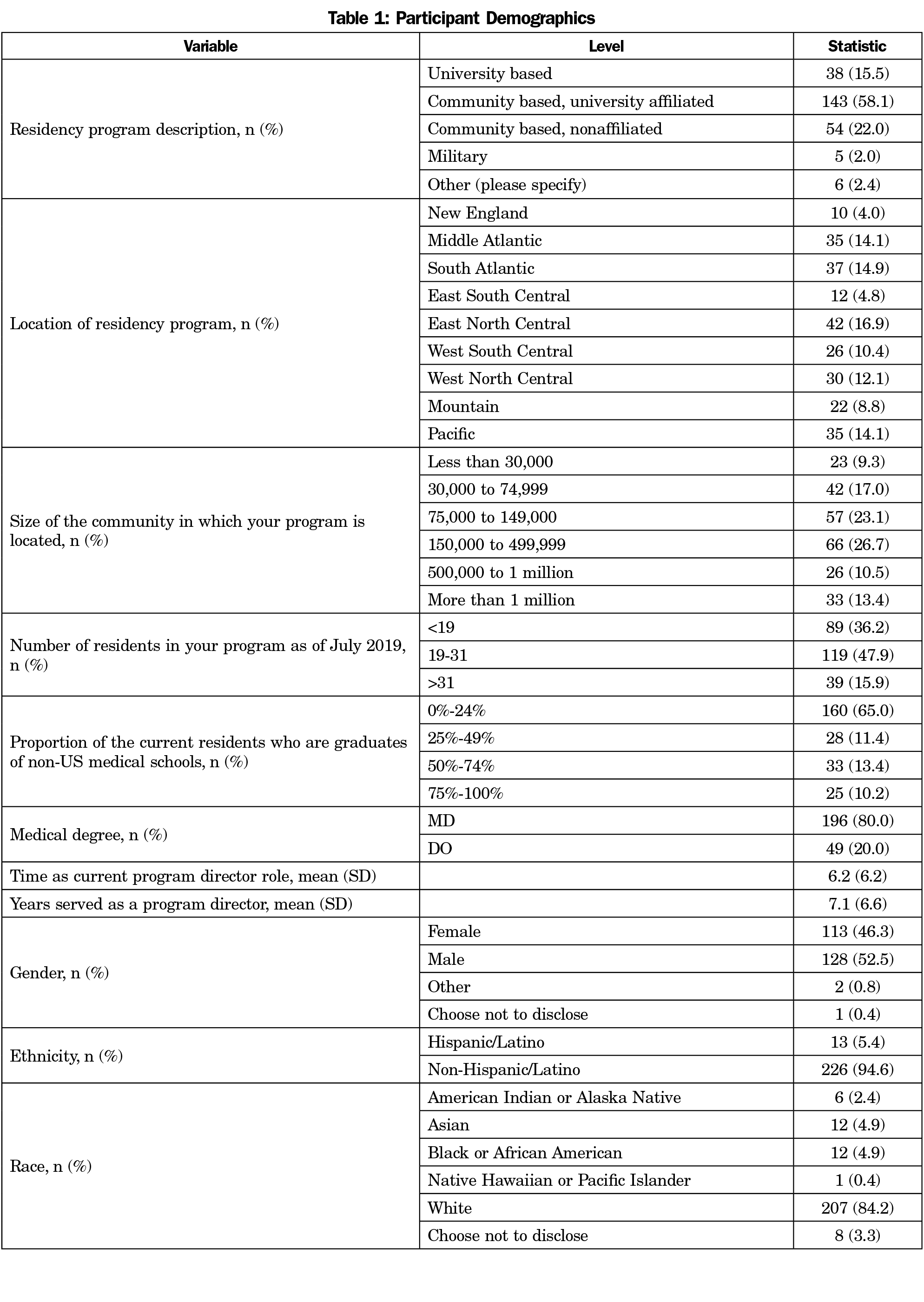

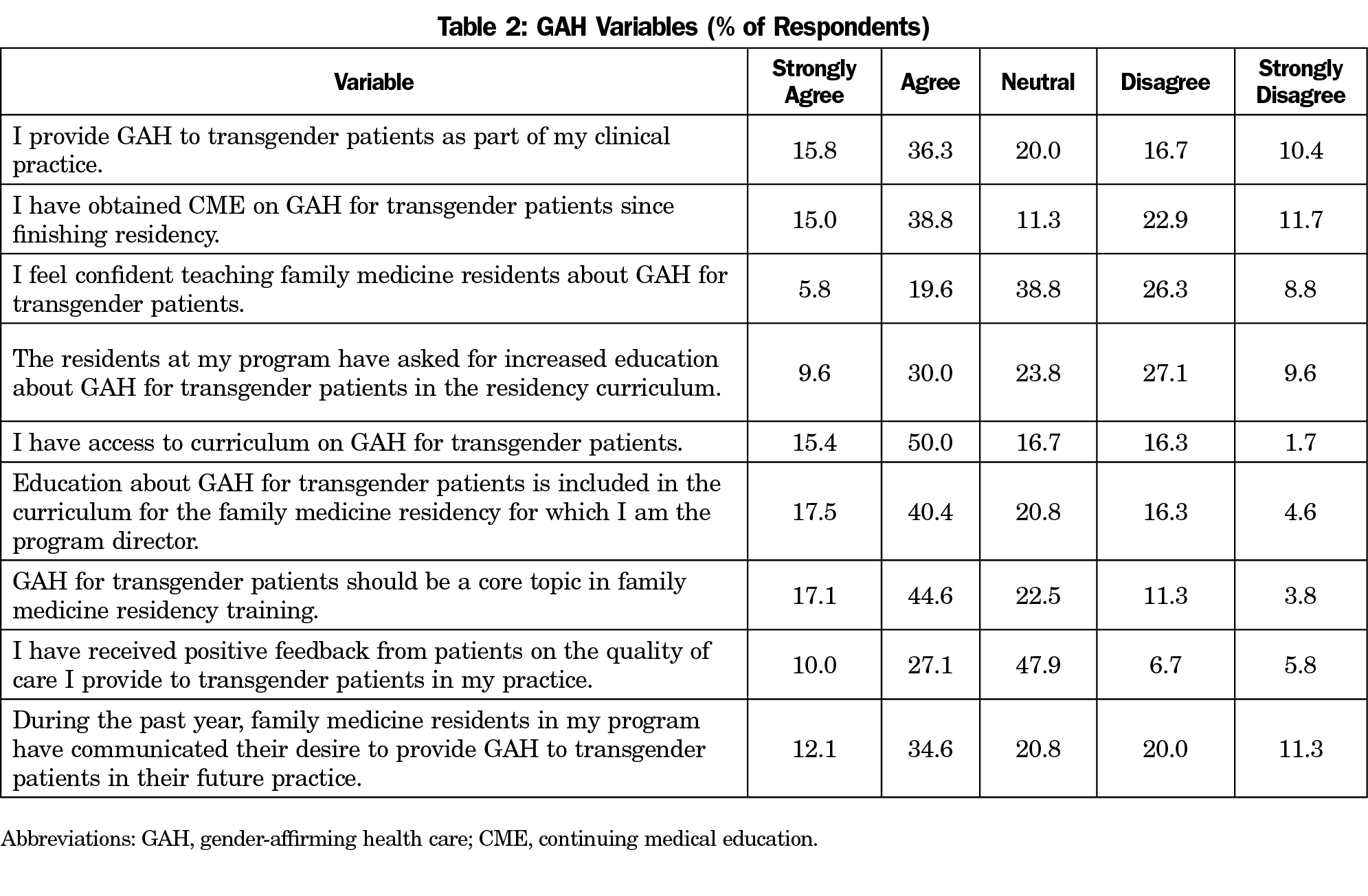

Table 1 shows the demographics of the program directors and their residency programs. Table 2 presents PDs’ survey responses to questions related to GAH.

Perceived Barriers

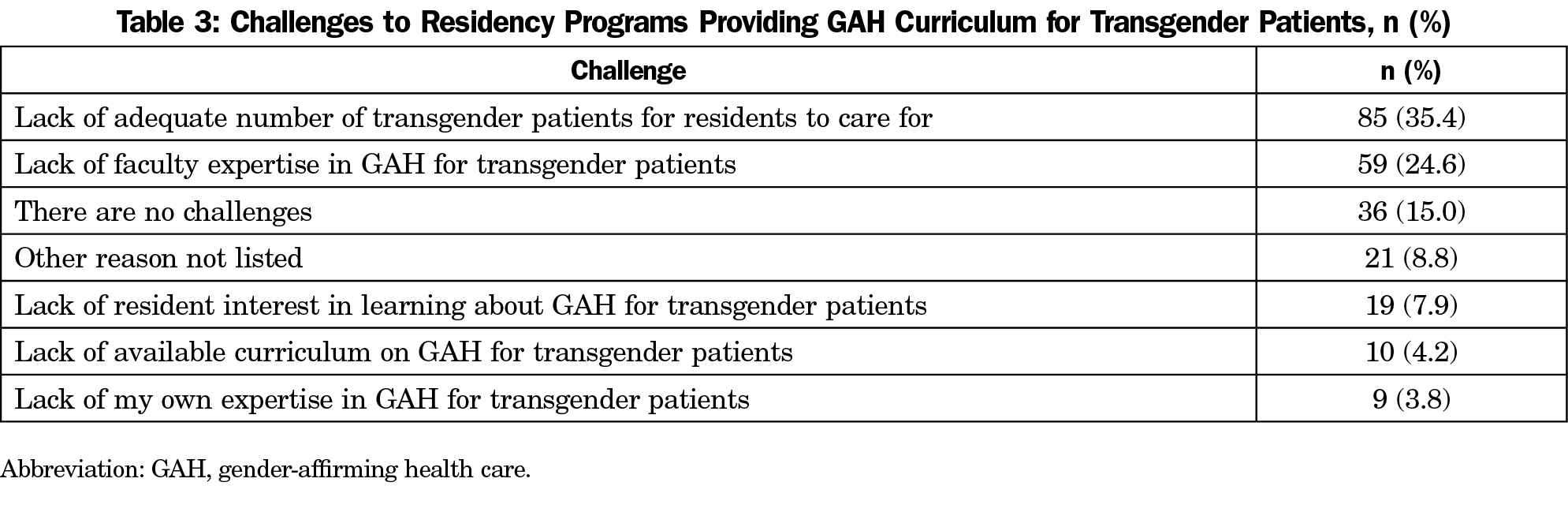

Table 3 presents challenges that PDs had to including GAH curriculum. The two perceived challenges that were noted by the largest number of respondents were lack of adequate number of transgender patients for residents to provide care (35.4%) and lack of faculty expertise in GAH for transgender patients (24.6%). Additional perceived challenges were lack of resident interest in learning about GAH for transgender patients (7.9%), lack of available curriculum on GAH for transgender patients (4.2%), and lack of PD expertise in GAH for transgender patients (3.8%). Interestingly, 15.0% of respondents indicated having no challenges to including GAH for transgender patients in the curriculum.

Likelihood of Including Gender-Affirming Care for Transgender Patients in the Curriculum

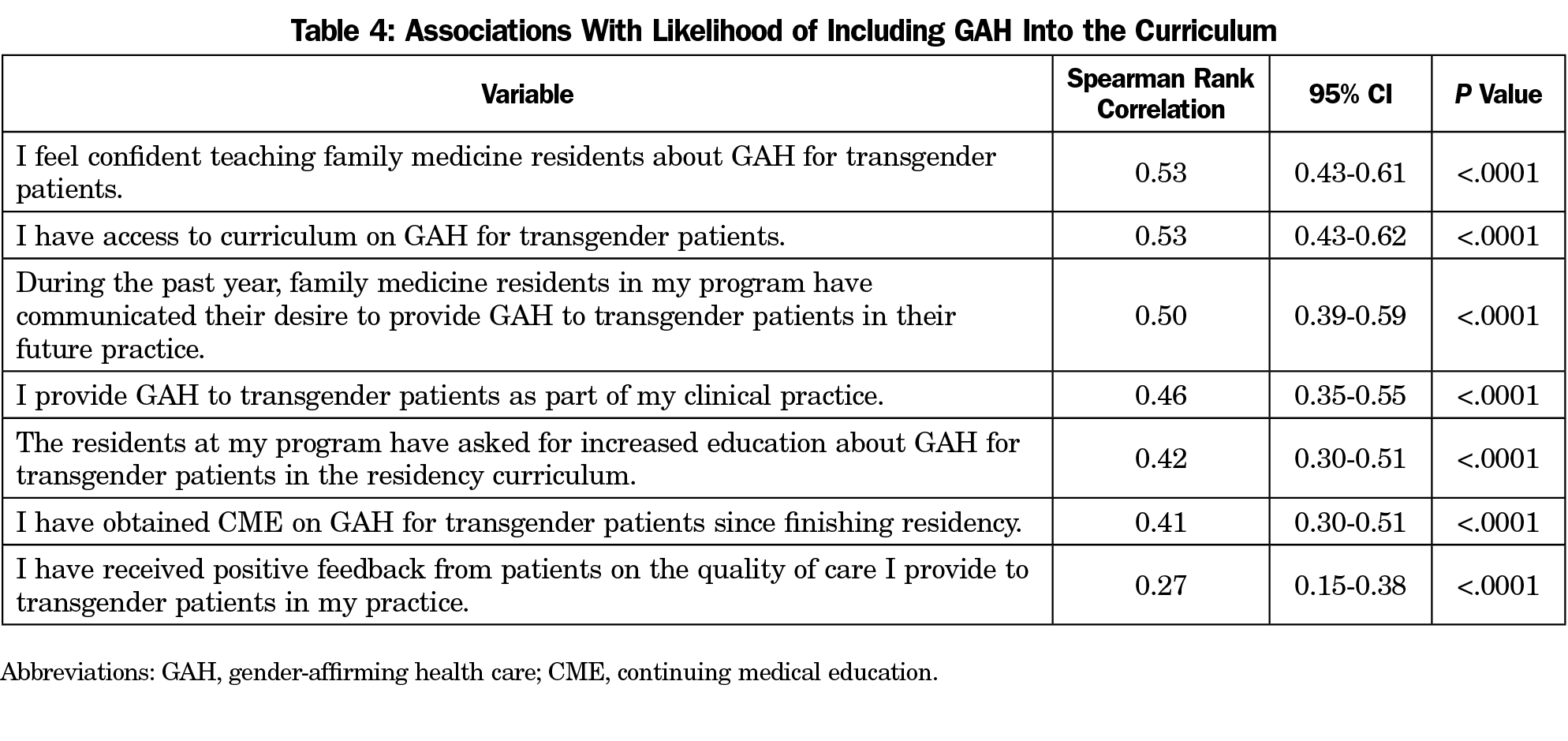

Table 4 presents correlations between the likelihood of including GAH in the curriculum with the PDs survey responses. Spearman rank correlations were mostly moderate in strength, with the exception of positive feedback from patients on the quality of care PD’s provide to their patients which was weak in strength (P<.0001). All correlations were positive, indicating increasing agreement with all other transgender health care variables was associated with increasing agreement with likelihood of including GAH into residency curriculum. The two responses that were most strongly associated with inclusion of GAH in curriculum were confidence of PDs in teaching GAH to residents (P<.0001) and access to curriculum on GAH (P<.0001). The remaining four had moderate strength associations with inclusion of GAH in curriculum, in descending order: (1) residents communicating their desire to provide GAH to transgender patients in their future practice (P<.0001), (2) PDs providing GAH to transgender patients in their clinic practice (P<.0001), (3) residents requesting GAH training (P<.0001), and (4) PDs having obtained continuing medical education in GAH since completing residency (P<.0001).

Those who strongly agreed or agreed with being adept at and/or comfortable teaching about GAH for transgender patients had a significantly (P<.0001) higher median likelihood of including GAH into residency curriculum (median: 4.0, Q1-Q3: 4.0-5.0) compared to those who disagreed or strongly disagreed with being adept and/or comfortable (median: 3.0, Q1-Q3: 2.0-4.0); 57.9% of PDs strongly agreed or agreed that GAH-specific education was already included in their residency program.

Certain program characteristics were associated with an increased likelihood of GAH education being included in residency curriculum, with university-based programs having a significantly higher median likelihood than community-based programs (P=.0027).

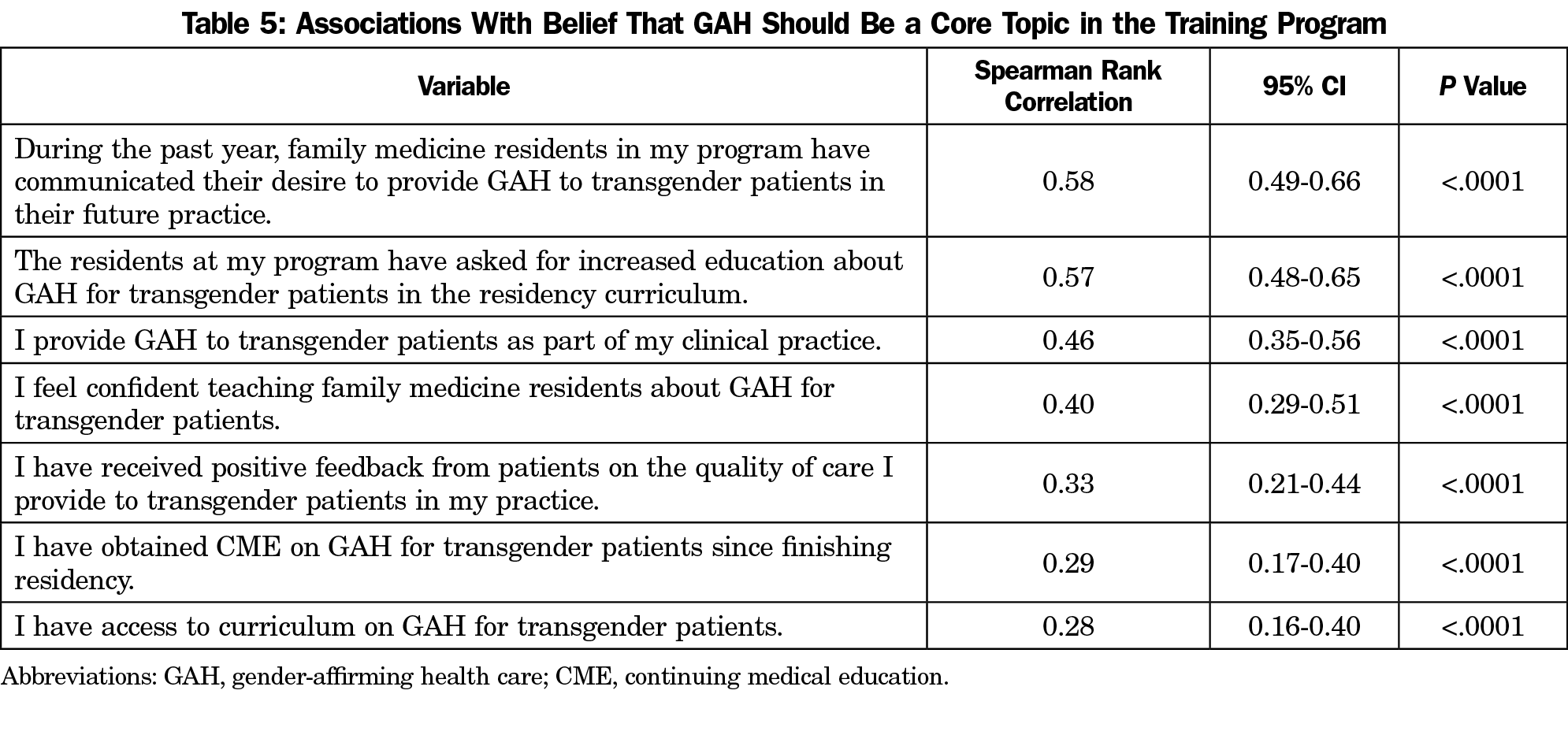

Belief That Gender-Affirming Care Should Be a Core Topic in Family Medicine Training

Table 5 presents correlations between belief that GAH should be a core topic in family medicine training, with the PDs’ survey responses. We used Spearman rank correlation to analyze the association among various characteristics of the PDs and their programs with the likelihood of PD’s belief that GAH should be a core competency in family medicine residency. Spearman rank correlations were weak to moderate in strength and all correlations were positive, indicating that increasing agreement with belief that GAH should be a core topic in the training program was associated with increasing agreement of all other transgender health care variables. The two responses that had the strongest associations with PDs believing that GAH should be a core competency in resident training were residents communicating their desire to provide GAH to transgender patients in their future practices (P<.0001) and the residents asking for increased education in GAH (P<.0001). After these, the two other variables with moderate strength associations with PDs believing that GAH should be a core topic in training were (in descending order): (1) PDs providing GAH to transgender patients as part of their clinical practice (P<.0001), and (2) PDs feeling confident teaching residents about GAH for transgender patients (P<.0001). The weakest associations, in descending order, were with (1) PDs receiving positive feedback on the quality of care they provide to transgender patients in their practice (P<.0001), (2) PDs obtaining CME in GAH for transgender patients since completing residency (P<.0001), and (3) PDs having access to curriculum on GAH for transgender patients (P<.0001).

PD belief that GAH should be a core competency in family medicine residency varied significantly by geographic location of the program; the Midwest (P=.0263) and South (P=.0035) had significantly lower medians than the West. Gender also showed a significant difference. Male PDs had significantly lower medians than female PDs (P=.0008).

Training in GAH for transgender patients has recently expanded in family medicine residencies, but still faces barriers.15 While 57.9% of respondents currently include GAH in their family medicine residency curriculum, 39.6% answered that they agreed or strongly agreed that their residents had requested increased education in GAH, and 46.7% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that their residents had expressed a desire to provide GAH to transgender patients in their future practice. This suggests that resident interest and intention are important drivers and there is demand for more education. Based on this finding, it is important for continued work and scholarship around advocacy and education about GAH for transgender patients at all levels of medical training, including continuing education for practicing physicians.

Including Gender-Affirming Care for Transgender Patients in the Curriculum

The two aspects of PD responses that were most associated with inclusion of curriculum on GAH for transgender patients were confidence of PDs in teaching GAH to residents and access to curriculum on GAH. This indicates the importance of resources available for PDs to increase their own knowledge of GAH, including ready-made curriculum tools that PDs can access to easily teach their residents. However, while approximately half of PDs strongly agree or agree that they provide GAH to their own clinic patients (52.1%) and have obtained continuing medical education in GAH since residency (53.8%), and almost two-thirds have access to a curriculum on GAH (65.4%), only 25.4% report comfort teaching residents about the topic. This suggests that attending CME or having access to a preexisting curriculum alone is insufficient to improve PD confidence in educating others on the topic. Surprisingly, even physicians who are providing GAH in their practice reported lack of confidence in providing education to residents, with less than half (47.2%) feeling comfortable teaching GAH to residents and 15.2% feeling specifically uncomfortable teaching GAH to residents. Those PDs who reported being comfortable teaching GAH had a significantly higher likelihood of including GAH into their residency curriculum compared to those who felt uncomfortable teaching GAH. Further exploration of factors to improve confidence in teaching is necessary and models that address the gap between confidence and competence are required.26

Belief That Gender-Affirming Care Should Be a Core Topic in Family Medicine Training

Two aspects associated with a PD’s belief that GAH for transgender patients should be a core topic in family medicine residency worth noting are (1) residents communicating their desire to provide GAH to transgender patients in their future practice, and (2) residents asking for increased education in GAH. These findings highlight the relationship between residents’ desires on PDs’ beliefs about family medicine education and the future of the specialty. These findings also suggest PDs are responsive to the perceived GAH educational needs communicated by residents. Continued advocacy regarding the importance of having the ability to provide GAH to patients may enhance the number of residents asking for further education in this area and help push curricular reform in future residencies.

PD belief that GAH should be a core competency in family medicine residency varied significantly by geographic location of the program; the Midwest and South had significantly lower medians than the West. Gender also showed a significant difference. Male PDs had significantly lower medians than female PDs. Further research should explore what contributes to the discrepancy in the value placed on GAH depending on geographic location and gender.

Strengths

This survey targeted the study of GAH curriculum in family medicine residencies specifically, whereas previous research has grouped several specialties together,15 or did not target family medicine residencies (eg, pediatric studies). The survey was distributed to family medicine PDs across the United States and Canada, from both rural and urban communities.

Limitations

As part of the survey, PDs were asked to respond to questions about their past experiences, which exposes this study to reporting and recall bias. However, it is anticipated that these biases are likely uniformly distributed across respondents.

The survey was cross-sectional and thus limited to finding associations between variables, rather than causation. The information gathered reflects only a single point in time. Questions were limited by the nature of the survey process itself. Data on those PDs choosing not to answer or selectively choosing to omit answers to specific questions are also unavailable.

The Likert-style responses of the survey are subjective in their gradation. The option to answer “neutral” is necessary, however, it reduces the pool of answers from which data could be derived.

There are limitations in generalizability. The respondents were 84% White, 53% male, and 58% were from community-based, university-affiliated programs.

Implications for Future Practice

Despite increasing awareness of challenges that transgender patients face, barriers still exist to include training in GAH in family medicine residency. This study identified characteristics of programs and PDs that have included curriculum on GAH. Some of the characteristics are not modifiable, but future research can address modifiable characteristics.

It is evident that PDs will benefit from the availability of a curriculum on GAH and increased opportunities related to continuing medical education and faculty development with a GAH focus. PD and other faculty require access to faculty development related to the teaching of GAH to capitalize on existing curricula, improve confidence in teaching GAH, and support resident interest in this area. Strategies to increase the transgender patient census in resident clinic practices (inclusive intake forms and processes, advertising transgender-friendly status, community outreach, etc) are required to address patient need and to further build trusting and therapeutic relationships between physicians and transgender patients.

All communities need family physicians who are competent providers of GAH to transgender patients.24 Curriculum development is critical to support further educational efforts, and future research should target specific interventions for improving GAH education for family medicine residents regardless of the location of their residency.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Heather Paladine, MD, Columbia University, Department of Family Medicine; Elizabeth Arnold, PhD, LCSW; and Chance R. Strenth, PhD, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Department of Family and Community Medicine, for their assistance in editing the survey questions.

References

- Gardner IH, Safer JD. Progress on the road to better medical care for transgender patients. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013;20(6):553-558. doi:10.1097/01.med.0000436188.95351.4d

- Stroumsa D. The state of transgender health care: policy, law, and medical frameworks. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):e31-e38. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301789

- Roberts TK, Fantz CR. Barriers to quality health care for the transgender population. Clin Biochem. 2014;47(10-11):983-987. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.02.009

- Fallin-Bennett K. Implicit bias against sexual minorities in medicine: cycles of professional influence and the role of the hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):549-552. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000662

- White Hughto JM, Reisner SL, Pachankis JE. Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2015;147:222-231. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010

- Cruz TM. Assessing access to care for transgender and gender nonconforming people: a consideration of diversity in combating discrimination. Soc Sci Med. 2014;110:65-73. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.032

- Buchholz L. Transgender care moves into the mainstream. JAMA -. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1785-1787. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.11043

- Grant JM, Mottet L, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman JL, Keisling M. Injustice at every turn: a report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington, DC, National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2011. doi:10.1016/S0016-7878(90)80026-2

- Khalili J, Leung LB, Diamant AL. Finding the perfect doctor: identifying lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-competent physicians. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(6):1114-1119. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302448

- Bonvicini KA. LGBT healthcare disparities: what progress have we made? Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(12):2357-2361. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2017.06.003

- McPhail D, Rountree-James M, Whetter I. Addressing gaps in physician knowledge regarding transgender health and healthcare through medical education. Can Med Educ J. 2016;7(2):e70-e78. doi:10.36834/cmej.36785

- Safer JD, Pearce EN. A simple curriculum content change increased medical student comfort with transgender medicine. Endocr Pract. 2013;19(4):633-637. doi:10.4158/EP13014.OR

- Hafferty FW, Franks R. The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Acad Med. 1994;69(11):861-871. doi:10.1097/00001888-199411000-00001

- Dubin RE, Kaplan A, Graves L, Ng VK. Acknowledging stigma: its presence in patient care and medical education. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(12):906-908.

- Coutin A, Wright S, Li C, Fung R. Missed opportunities: are residents prepared to care for transgender patients? A study of family medicine, psychiatry, endocrinology, and urology residents. Can Med Educ J. 2018;9(3):e41-e55. doi:10.36834/cmej.42906

- World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of care for health of transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people, seventh version. September 2011. http://www.wpath.org/publications_standards.cfm.

- Vagias WM. Likert-type scale response anchors. Clemson International Institute for Tourism & Research Development, Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management. Clemson University; 2006.

- Deutsch, Madeline B. Overview of gender-affirming treatments and procedures. UCSF Transgender Care & Treatment Guidelines. June 17, 2016.

- Trum HW, Hoebeke P, Gooren LJ. Sex reassignment of transsexual people from a gynecologist’s and urologist’s perspective. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(6):563-567. doi:10.1111/aogs.12618

- Richmond KA, Burnes T, Carroll K. Lost in trans-lation: interpreting systems of trauma for transgender clients. Traumatology. 2012;18(1):45-57. doi:10.1177/1534765610396726

- American Association of Children’s Residential Centers. Trauma informed care in residential treatment. Residential Treat Child Youth. 2014;31(2):97-104. . 918429 doi:10.1080/0886571X.2014.918429

- Marr A, Tang K, Feder SH, Khatchadourian K, Lawson ML, Robinson A. Gender diversity training in Canadian paediatric postgraduate medical education: A needs assessment survey. Paediatr Child Health. 2019;26(2):e89-e95. doi:10.1093/pch/pxz144

- Mainous AG III, Seehusen D, Shokar N. CAFM Educational Research Alliance (CERA) 2011 Residency Director survey: background, methods, and respondent characteristics. Fam Med. 2012;44(10):691-693.

- Kano M, Silva-Bañuelos AR, Sturm R, Willging CE. Stakeholders’ recommendations to improve patient-centered “LGBTQ” primary care in rural and multicultural practices. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(1):156-160. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2016.01.150205

- Mansouri M, Lockyer J. A meta-analysis of continuing medical education effectiveness. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2007;27(1):6-15. doi:10.1002/chp.88

- MacKinnon KR, Ross LE, Rojas Gualdron D, Ng SL. Teaching health professionals how to tailor gender-affirming medicine protocols: a design thinking project. Perspect Med Educ. 2020;9(5):324-328. doi:10.1007/s40037-020-00581-5

There are no comments for this article.