Background and Objectives: The American Osteopathic Association (AOA) agreed to combine its graduate medical education programs with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) between July 1, 2015 and June 30, 2020 in an initiative called the Single Accreditation System (SAS). The objective of our study was to identify the impact the SAS had on the ACGME, family medicine (FM), and implications for the future of FM.

Methods: We collected and compiled data from the AOA, ACGME, and the National Residency Matching Program (NRMP). Analysis reveals the effects that the addition of former 122 AOA-accredited FM residencies had on the ACGME and FM programs.

Results: Several osteopathic FM programs encountered challenges meeting ACGME accreditation standards. As of June 1, 2020, 89 of 122 accreditation applications received initial or continuing accreditation; the others had accreditation issues to resolve. The Osteopathic Recognition program emphasizing training in osteopathic principles and practices was a popular option in FM residencies. Fewer DOs serve as program directors in former AOA-accredited FM residencies.

Conclusions: The SAS has shifted the balance in the percentages of MDs, DOs, and international medical graduates (IMGs) in FM. Trends in FM show that as more DOs enter the NRMP the percent of MDs and IMGs decreases. In the future, it is projected that DOs will outnumber MDs and IMGs in ACGME FM residencies. The 51 new medical schools started between 2010 and 2020 will generate a test for the integration of their graduates into GME. Increased competition for FM residencies is expected.

Negotiations between the American Osteopathic Association (AOA), the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine (AACOM), and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) concluded on August 26, 2014 with an agreement to create a Single Accreditation System (SAS) for graduate medical education (GME).¹ The AOA agreed to have its accredited GME programs apply for and comply with ACGME accreditation standards over a 5-year period starting on July 1, 2015 and ending on June 30, 2020. For FM, ACGME accreditation decisions are made by the FM Review Committee comprised of 10 MDs, three DOs, and one public member. At the end of the transition period, the AOA closed its GME accreditation operations.

The history of AOA-accredited family medicine residencies in the SAS is only understood with background information. In 2014, the AOA had 252 FM residency programs,² yet only 131 applied for ACGME accreditation by June 2020.³ Nine AOA-accredited FM programs later withdrew from the SAS, leaving 122 programs that achieved ACGME accreditation. In the same year, the ACGME had 483 FM programs.4 Accounting for the other 121 AOA programs is rooted in the past, starting in the late 1990s when ACGME FM programs began acquiring AOA accreditation. In March 2005 there were 107 programs holding AOA and ACGME accreditation, the overwhelming majority in FM.5 As of July 1, 2015, there were 175 such programs, again dominated by FM.6 In the SAS, programs with AOA/ACGME accreditation were already fully compliant and needed only to voluntarily drop their AOA accreditation status. While not all AOA FM programs applied to the ACGME, approximately 121 FM programs in 2014 held AOA and ACGME accreditation.

Prior to the proliferation of FM programs with AOA and ACGME accreditation, the majority of DOs were already in ACGME FM residencies. In 1991, for example, there were 368 DO residents in AOA programs7 and 692 DO residents (59% of all FM DOs) in ACGME programs. In addition, DOs represented 10.5% of all ACGME FM residents in 1991.8 The onset of programs with AOA/ACGME accreditation since 1997 made it challenging to compile accurate numbers of DOs in FM since both the AOA and the ACGME included DOs in their respective resident counts.

The intent of the AOA was to have its programs obtain ACGME accreditation, however, not all FM programs managed to achieve accreditation without contingencies. AOA standards for FM accommodated smaller rural programs that allowed residencies to operate with less exacting requirements. It proved challenging for many osteopathic FM residencies to address differences in accreditation standards.

As part of SAS, a new ACGME accreditation program was created to incorporate osteopathic principles and practices, on a voluntary basis, into GME training.¹ All programs have the option to apply for and meet existing ACGME standards for Osteopathic Recognition as an add-on component to their residency. It is designed to provide ongoing training in osteopathic principles and practices for DOs and interested MDs throughout the residency. Osteopathic Recognition has its own set of standards, conducts on-site reviews, and determines compliance by the Osteopathic Principles Committee comprised of 14 DOs, one MD, and one public member.9

In June 2020, 147 FM programs had Osteopathic Recognition, more than the former 122 AOA-accredited FM residencies in the SAS.¹0 To a large extent, the additional ACGME programs that acquired Osteopathic Recognition formerly held AOA accreditation and had previous exposure to osteopathic principles and practices and decided to offer this option to interested DOs as a feature of their residency.

The recent past has been a period of dynamic growth in osteopathic medicine. In 2013, there were 37 teaching locations for colleges of osteopathic medicine (COMs); in 2020 that number was 57.¹¹ Now with only one option for GME training, the ACGME inherits the challenge of partnering with the osteopathic profession in matching its growth for both current and yet-to-come DOs. This collaboration has important future implications for FM due to osteopathic medicine’s emphasis on primary care and the high percentage of its graduates who pursue careers in FM.

We used published data from the ACGME, AACOM, AOA, the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP), the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME), and the American Medical Association (AMA) to examine the historical background and results of AOA-accredited FM program applications to the ACGME from 2015 to 2020. From these sources, we compiled data on the changes engendered by the SAS on program director leadership, the inclusion of osteopathic training (Osteopathic Recognition), and the number of DOs incorporated into FM under the ACGME. We also examined growth in the number of LCME and Commission on Osteopathic College Accreditation (COCA)-accredited medical schools between 2010-2020, student enrollment, and the impact of additional medical graduates on GME and FM.

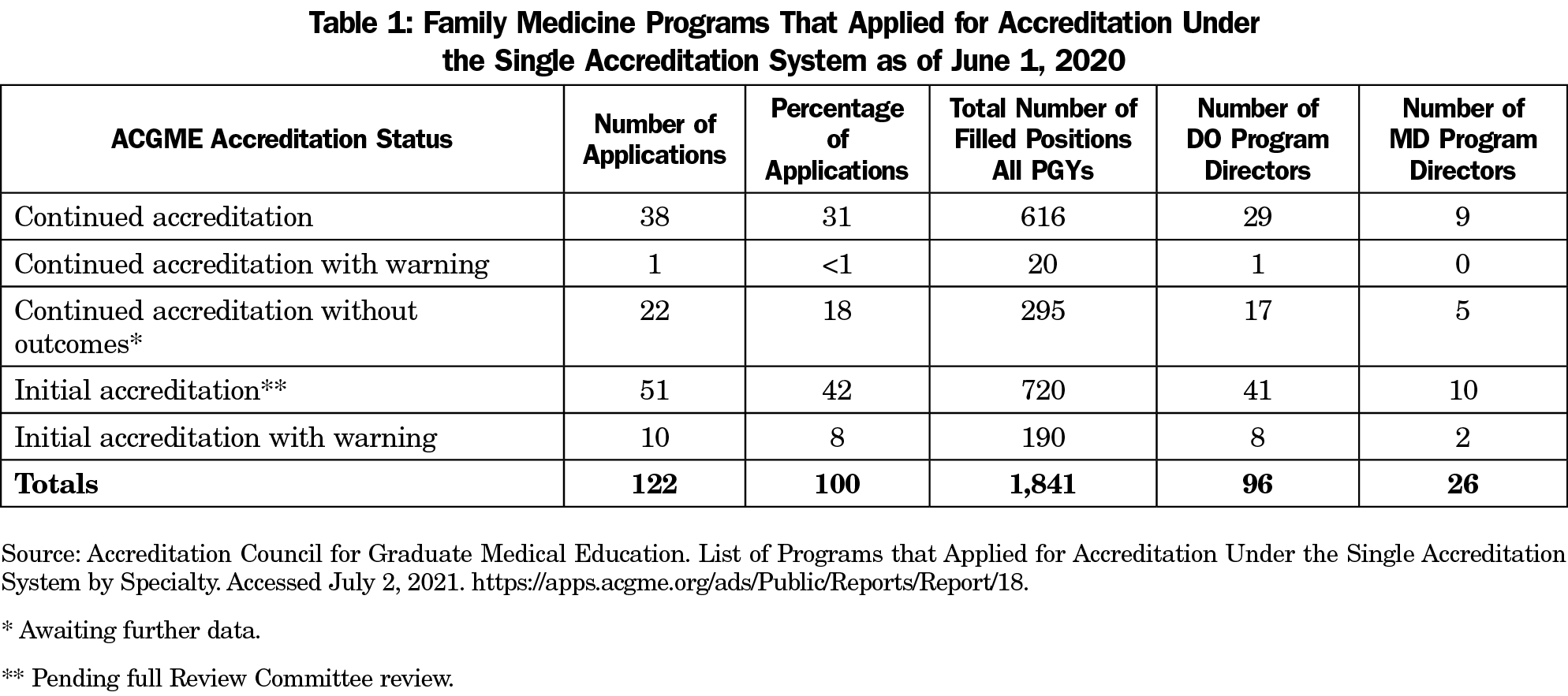

We compiled publicly available data from the ACGME’s List of Programs that Applied for Accreditation Under the SAS by Specialty to analyze FM (Table 1).¹² The ACGME report included data on the following fields: program number, name, address, program director, accreditation status, effective date, and specialty for 131 AOA-accredited FM programs. Additional data to obtain the total number of filled positions for each AOA-accredited program in the SAS were obtained from the Advanced Program Search option on the ACGME website.¹³ In Table 1, the authors used the total number of filled positions reported as of June 1, 2020, which correspond to the ACGME decisions on AOA-accredited FM applications. For the purposes of this study, we condensed data to include only the former 122 AOA-accredited FM residencies, excluding the nine AOA-accredited FM programs that withdrew from the ACGME.

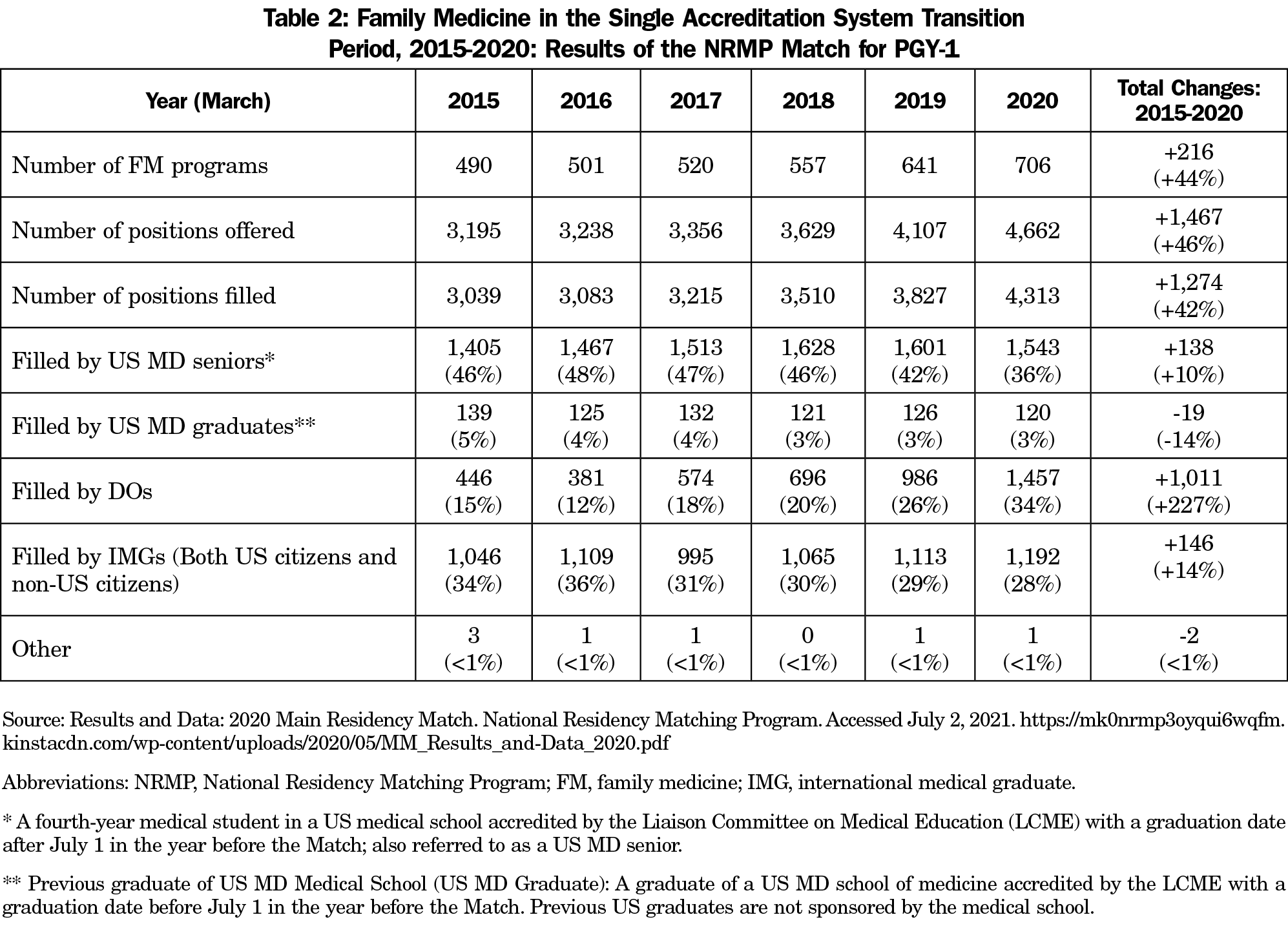

We examined the impact of the SAS from the results of the NRMP’s Results and Data reports for the years 2015-2020 in the Main Residency Match (Table 2).14 Data analyzed include the number of programs participating in the Match by specialty, specialty by postgraduate year (PGY) level, number of positions, number filled, US MD senior, US MD graduate, osteopathic, Canadian, fifth pathway, US IMG, non-US IMG, other, and number unfilled. For this study, the authors selected the PGY-1 level to compare match rates from 2015 to 2020. The total number of US IMGs and Non-US IMGs were combined into one line item labeled “filled by IMGs” and likewise Canadians and others were labeled as “other.” Table 2 does not include the number of unfilled positions for the 5-year period or ACGME positions in FM filled through other modalities, such as the Military Match.

Table 1 reflects the ACGME FM Review Committee decisions on the former 122 AOA-accredited ACGME applications as of June 1, 2020. The total number of filled residency positions for the 122 applications was 1,841, which included all PGY levels. In terms of program directors, 26 were MDs and 96 DOs.

Of the 122 applications, 38 programs received Continued Accreditation. There were 51 programs awarded Initial Accreditation, but those now await a full inspection within two years, when a decision will be made whether to grant Continued Accreditation. Continued Accreditation without Outcomes status was awarded to 22 programs due to insufficient data to confer Continued Accreditation status. Ten programs were cited for initial accreditation with warning. One program cited with continued accreditation with warning has areas of noncompliance that may jeopardize its accreditation status. See Table 1 for a breakdown of program director leadership (DO vs MD) and the number of residents in these programs.

Table 2 illustrates the growth in FM residencies participating in the NRMP and the impact of DO graduates during the 5-year transition to the SAS. Data indicates a significant increase (44%) in the number of FM programs participating in the NRMP, trending from 490 programs in 2015 to 706 programs in 2020, a gain of 216. The corresponding number of FM positions offered in the NRMP also increased from 3,195 to 4,662, a gain of 1,467 slots, or 46%. Additionally, the number of positions filled increased from 3,039 to 4,313, a gain of 1,274 slots (42%). The number of positions filled by US MD Seniors increased from 1,405 to 1,543, a gain of 138 (10%); the number of positions filled by US MD graduates decreased from 139 to 120, a loss of 19 (-14%); the number of positions filled by DOs increased from 446 to 1,457, an increase of 1,011 (227%); the number of positions filled by IMGs increased from 1,046 to 1,192, a gain of 146 (14%) and the number of positions filled by others decreased from three to one, a loss of two.

As of June 2020, 236 eligible programs applied for Osteopathic Recognition.¹5 Compared to former AOA-accredited residencies in all medical specialties, the popularity with Osteopathic Recognition is most evident in FM. Of the 236 programs with Osteopathic Recognition, 147 (62%) are in FM. As of June 2020, 147 of the 699 (21%) ACGME FM programs provide programs with Osteopathic Recognition.¹5

Prior to applying for ACGME accreditation, osteopathic FM residencies had to first address differences in accreditation standards. Comparatively, the ACGME standards are more detailed and prescriptive (62 pages)11 than the former AOA standards (21 pages).11 Osteopathic FM standards accommodated smaller, rural programs that allowed residencies to operate with a smaller minimum number of residents (6 versus 12), with fewer core faculty, a less defined patient mix for residents, less protected time for faculty, and lower expectations in meeting faculty scholarly activity, among other accreditation standards. Once these and other differences were addressed, AOA-only accredited programs could apply to the ACGME after July 1, 2015.

Attrition in AOA-accredited FM programs was expected. The nine applications that either voluntarily withdrew or had ACGME withdrawal represent 7.4% of applicants. As of June 1, 2020, 89 (73%) of former AOA-accredited FM residencies received either initial accreditation (42%) or continued accreditation status (31%). FM programs rank in the middle compared to other AOA specialties in achieving ACGME status. They did not do as well as internal medicine, which had 88% of its residencies earn either initial or continued accreditation, but did better than other specialties, such as OB/GYN and general surgery.¹²

While former AOA-accredited FM residencies may have fared well compared to other osteopathic programs in the SAS, they did poorly when measured against all other ACGME-accredited FM programs. As of June 1, 2020, former AOA-accredited FM residencies in the SAS represent 17% (122 of 699) of all accredited FM residencies. Out of the total of 699 ACGME-accredited FM residencies, 37 programs held the status of continued accreditation without outcomes.¹8 Of the 37, 22 (59%) were former AOA-accredited FM residencies. Of more serious concern are the former AOA-accredited FM residencies that received accreditation with warning. As of June 1, 2020, a total of 22 of 699 FM residencies had accreditation with warning status and 10 (45% ) are former AOA-accredited FM residencies.¹8 The failure and/or inability to correct cited deficiencies can result in a voluntary withdrawal or having ACGME accreditation withdrawn. A real potential exists for additional attrition of former AOA-accredited FM programs.

Table 2 illustrates the growth in the number of ACGME FM residencies and the impact of DOs during the 5-year period of the SAS. Also noteworthy are the 92 additional ACGME FM applications—not part of SAS—that were approved during that time span. Combined with the 122 former AOA-accredited FM programs in the SAS, this generated a 46% increase in the number of PGY-1 FM positions offered in the NRMP between 2015 and 2020. This dramatic increase in the number of offered FM positions went a long way in providing a cushion to accommodate the influx of DOs. With the ending of the AOA Match 2019, the primary option for residency placement for the DO graduating class of 2020 was the NRMP.

Even with the additional new FM positions between 2015 and 2020, the inclusion of DO graduates brought noticeable changes to FM. In terms of numbers, 446 DOs matched in the 2015 NRMP compared to 1,457 in 2020. Between 2015 and 2020 in the NRMP, DOs moved up from 15% to 34% of candidates selected for a PGY-1 slot. Correspondingly, the MD senior contingent shrank from 46% to 36%, as did the IMG physician population from 34% to 28%. Surprisingly, the number of MD and IMG physicians matching in the NRMP increased between 2015 and 2020, yet their percentage of the FM PGY-1 population in the NRMP dropped as they were surpassed by the entry of the large number of DOs. DOs, as a group, accounted for 19% of all matched physicians in the 2020 NRMP.19 Overall, 23.3% of the DO graduating class of 2020 in the NRMP matched into FM, compared to 8.5% for MD graduates.20

Decisions to submit applications to the ACGME in the SAS were made by hospitals with AOA-accredited FM programs. Under AOA accreditation policies, the program director, with rare exceptions, was required to be a DO. It is noteworthy that 26 (21%) of the former 122 AOA-accredited FM residencies with ACGME accreditation have an MD program director (Table 1). This outcome can be seen from two perspectives. One is that the 122 former AOA-accredited FM residencies are quickly integrating into the ACGME and leadership positions are filled with the most qualified person. The other view is that DOs lost a sizable number of leadership positions in the consolidation of programs and residents will see fewer osteopathic role models in programs they formerly directed. One outcome of the SAS is that most of the approximately 121 DO program directors of AOA/ACGME-accredited FM programs were eliminated. Regardless of interpretation, the reality is that the 122 hospitals with AOA-accredited FM programs made decisions independent of the AOA.

To become a licensed physician in the United States requires completion of two distinct phases: medical school and GME training. The two phases are closely linked yet independent and operate under separate accreditation programs. All GME is now accredited by the ACGME. During the decade 2010-2020, the LCME accredited 24 new allopathic medical schools, of which eight will only graduate their inaugural class between 2021 and 2024.21 Growth on the osteopathic side was even larger, with 27 new medical schools, branch campuses, and additional locations; 13 of them have yet to graduate their first class as of 2020.²²

Although the number of new MD and DO medical schools appear relatively close, there is one area of major difference: student enrollment. The LCME generally approves new medical schools with around 30-60 first-year students and then gradually permits increases in enrollment numbers as the program matures. The combined first-year enrollments for the newest eight MD medical schools can expect to generate at least 368 graduates per year by 2024.²³ Most new osteopathic medical schools start with 150 students. Based on the COCA-approved class sizes, the 13-newest DO training institutions will add a minimum of 1,750 graduates per year by 2024.11There will be an additional 2,100 freshly-minted MDs and DOs seeking residency training by 2024. The ability to successfully absorb these physicians by 2024 will depend in large part on programs maintaining their existing accreditation, their current resident numbers, and in the continued development of new residency programs.

Despite growth in the number of LCME-accredited medical schools, the increased numbers of MD graduates and FM residency positions, the interest level of MD graduates in FM has remained relatively flat over the past 6 years (Table 2). Slightly better are the numbers of IMGs. With 2020 serving as the base year, an increase of over 1,000 more DOs have matched with an ACGME FM residency compared to 2015. Much credit for this sizable jump goes to the SAS, yet DOs always had the choice to apply directly to the ACGME for GME training.

If current trends extend into the future, the SAS will have a profound impact on FM. The AOA FM programs that withdrew from the ACGME and any potential future attrition, either through voluntary withdrawal from the ACGME or through decisions of the FM Review Committee, had the impact of reducing GME opportunities and generating increased competition for trainees. The trends also indicate a popular residency choice for graduates of existing and new COMs will continue to be FM.24 Osteopathic physicians will be highly represented in the envisioned swelling applicant pool. We may see more programs adding Osteopathic Recognition to attract DOs. It is likely that DOs will continue to diminish the number and percent of IMGs in FM. DOs are currently a close second to MDs in the number and percentage of those entering FM. With DOs comprising a disproportionately larger number of post-2020 new medical school graduates, it would not be surprising to see DOs become the majority of FM residents in the near future as an important consequence of the SAS on FM.

Limitations

The AOA ceased publishing GME data in 2018 which precluded the authors from presenting numbers of its FM residencies and residents between 2015 and 2020. These same missing data prevented calculation of the number of AOA FM programs that acquired Osteopathic Recognition compared to other ACGME FM programs. During the SAS, successful former AOA-accredited FM residencies were added to the ACGME and simultaneously dropped from the AOA GME system, complicating the accurate counting of residents in the ACGME and AOA. Alternative pathways used by AOA-accredited FM residencies to join the ACGME outside of the SAS are not included in the data presented. Finally, it was not possible to distinguish the numerical impact on FM in the NRMP during the SAS that was generated by graduates from new COMs.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the thoughtful suggestions to improve this paper of Michael Opipari, DO, Thomas Gentile, MA, and Donald Sefcik, DO.

Opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors.

References

- Executive Summary of the Agreement Among the ACGME, AOA, and AACOM. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. August 26, 2014. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Nasca-Community/Executive_Summary_of_the_Agreement_between_ACGME_and_AOA.pdf

- Martinez B, Biszewski M. Appendix 1: Osteopathic Graduate Medical Education, 2018. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2018 Apr 1;118(4):269-273. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2018.052

- Family Medicine Programs that Applied for Accreditation Under the Single Accreditation System. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://apps.acgme.org/ads/Public/Reports/ReportRun

- Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate medical education, 2014-2015. JAMA. 2015 Dec 8;314(22):2436-54. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10473

- Cummings M, Kunkle JL, Doane C. Family medicine's search for manpower: the American Osteopathic Association accreditation option. Fam Med. 2006 Mar;38(3):206-10.

- Buser BR, Swartwout JE, Biszewski M, Lischka T. Single Accreditation System Update: A Year of Progress. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2018 Apr;118(4):264-268. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2018.051

- Baker HH, Wachtler J. Osteopathic graduate medical education. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1991 Nov;91(11):1128-40.

- Graduate Medical Education (Appendix 2). JAMA.1992;268(9):1170–1176. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03490090116028

- Osteopathic Recognition. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accessed June, 1, 2020. https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Recognition/Osteopathic-Recognition

- List of Programs Applying for and with Osteopathic Recognition by Specialty. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://apps.acgme.org/ads/Public/Reports/Report/17

- Number of Established and New COMs by Inaugural Class Year. American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine. Accessed June, 1, 2020.https://www.aacom.org/docs/default-source/data-and-trends/u-s-osteopathic-medical-schools-by-year-of-inaugural-class.pdf?sfvrsn=dc9e2997_20

- List of Programs that Applied for Accreditation Under the Single Accreditation System by Specialty. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://apps.acgme.org/ads/Public/Reports/Report/18.

- Advanced Program Search. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://apps.acgme.org/ads/Public/Programs/Search

- Results and Data: 2020 Main Residency Match. National Residency Matching Program. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://mk0nrmp3oyqui6wqfm.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/MM_Results_and-Data_2020.pdf

- Programs Applying For and With Osteopathic Recognition. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://apps.acgme.org/ads/Public/Reports/ReportRun.

- ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/120_FamilyMedicine_2020.pdf?ver=2020-06-29-161615-367

- Basic Standards for Residency Training in Osteopathic Family Medicine and Manipulative Treatment. American Osteopathic Association. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://osteopathic.org/wp-content/uploads/family-med-basic-standards.pdf

- List of Programs by Specialty. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://apps.acgme.org/ads/Public/Reports/ReportRun

- Results and Data: 2020 Main Residency Match. Table 4: Applicants in the Matching Program, 2016-2020. National Residency Matching Program. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://mk0nrmp3oyqui6wqfm.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/MM_Results_and-Data_2020.pdf

- Results and Data: 2020 Main Residency Match. Table 10 for MDs, and Table 11 for DOs. National Residency Matching Program. Accessed June 1, 2020.

https://mk0nrmp3oyqui6wqfm.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/MM_Results_and-Data_2020.pdf

- Accredited US MD Medical Schools in the United States. Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Accessed June 1, 2020. https://lcme.org/directory/accredited-u-s-programs/

- US Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine. American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine. Accessed June 1, 2020.https://www.aacom.org/become-a-doctor/u-s-colleges-of-osteopathic-medicine

- [Note] Information on the entering class size was gathered from the websites of the following eight newest LCME-accredited medical schools. Accessed June 1, 2020.

https://medschool.kp.org/student-life/admitted-students

https://uh.edu/medicine/admissions/faqs/

https://USMDschool.tcu.edu/

https://nyulangone.org/news/white-coat-ceremony-welcomes-first-class-nyu-long-island-school-medicine

https://www.shu.edu/medicine/news/first-school-of-medicine-class-reaches-milestone.cfm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carle_Illinois_College_of_Medicine

https://cusm.org/about/history.php

https://USMD.nova.edu/

- Phillips JP, Wendling A, Bentley A, Marsee R, Morley CP. Trends in US medical school contributions to the family physician workforce: 2018 update from the American Academy of Family Physicians. Fam Med. 2019;51(3):241-250. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2019.395617

There are no comments for this article.