Background and Objectives: Contraception is a core component of family medicine residency curriculum. Institutional environments can influence residents’ access to contraceptive training and thus their ability to meet the reproductive health needs of their patients.

Methods: Contraceptive training questions were included in the 2020 Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine residency program directors. The survey asked how many faculty and residents opt out of providing contraceptive methods for moral or religious reasons, and whether training sites have institutional restrictions on contraception. We performed descriptive statistics and regression to identify program characteristics associated with having a resident or faculty opt out of providing contraceptive care.

Results: Of 626 program directors, 249 responded to the survey, and 237 answered the contraceptive questions. Percentages of program directors reporting any residents or faculty who opted out of contraceptive services are as follows: pill/patch/ring (residents 27%; faculty 17%), emergency contraception (residents 40%, faculty 33%), or intrauterine devices/implants (resident 29%; faculty 23%). Programs in the South (OR 2.78; 1.19-6.49) and those with Catholic affiliation (OR 2.35; 1.23-4.91) had higher adjusted odds of at least one opt-out faculty but were not associated with having opt-out residents. Eleven percent of programs had at least one training site with institutional restrictions on contraception.

Conclusions: To ensure that residents have access to adequate contraceptive training, residencies should proactively seek faculty and training environments that meet residents’ needs, and should make limitations on services clear to potential residents and patients.

Patients rely heavily on family physicians for contraceptive care, yet the quality of contraceptive training in family medicine residency varies.1 Barriers to contraceptive training in family medicine residency include faculty members’ lack of accurate contraceptive knowledge,2 shortage of training opportunities for methods other than oral contraceptive pills (OCPs),1 and religious hospital affiliation.3 Some faculty opt out of contraceptive provision,4,5 which may impact resident training.

Our study examined the prevalence and predictors of two barriers to contraceptive training in family medicine residency: faculty members who do not provide contraception for moral or religious reasons, and institutional policies preventing contraceptive provision.

This survey was part of a survey conducted by the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) and sent to US family medicine residency directors.6 We collected data from May 11 to June 2, 2020.

The primary outcome was the program director’s report of whether their program had any faculty opting out of providing contraception (pill/patch/ring), emergency contraception, or intrauterine devices (IUDs)/implant placement (Table 2). We defined “opt out” to mean the physician does not provide contraception for moral or religious reasons. The secondary outcome was if there were any residents opting out of the same contraceptive services. We used χ2 and logistic regression to test which program characteristics were independently associated with having a faculty or resident opt out of providing any contraceptive service. We used SAS version 9.4 software. The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved this study in April 2020.

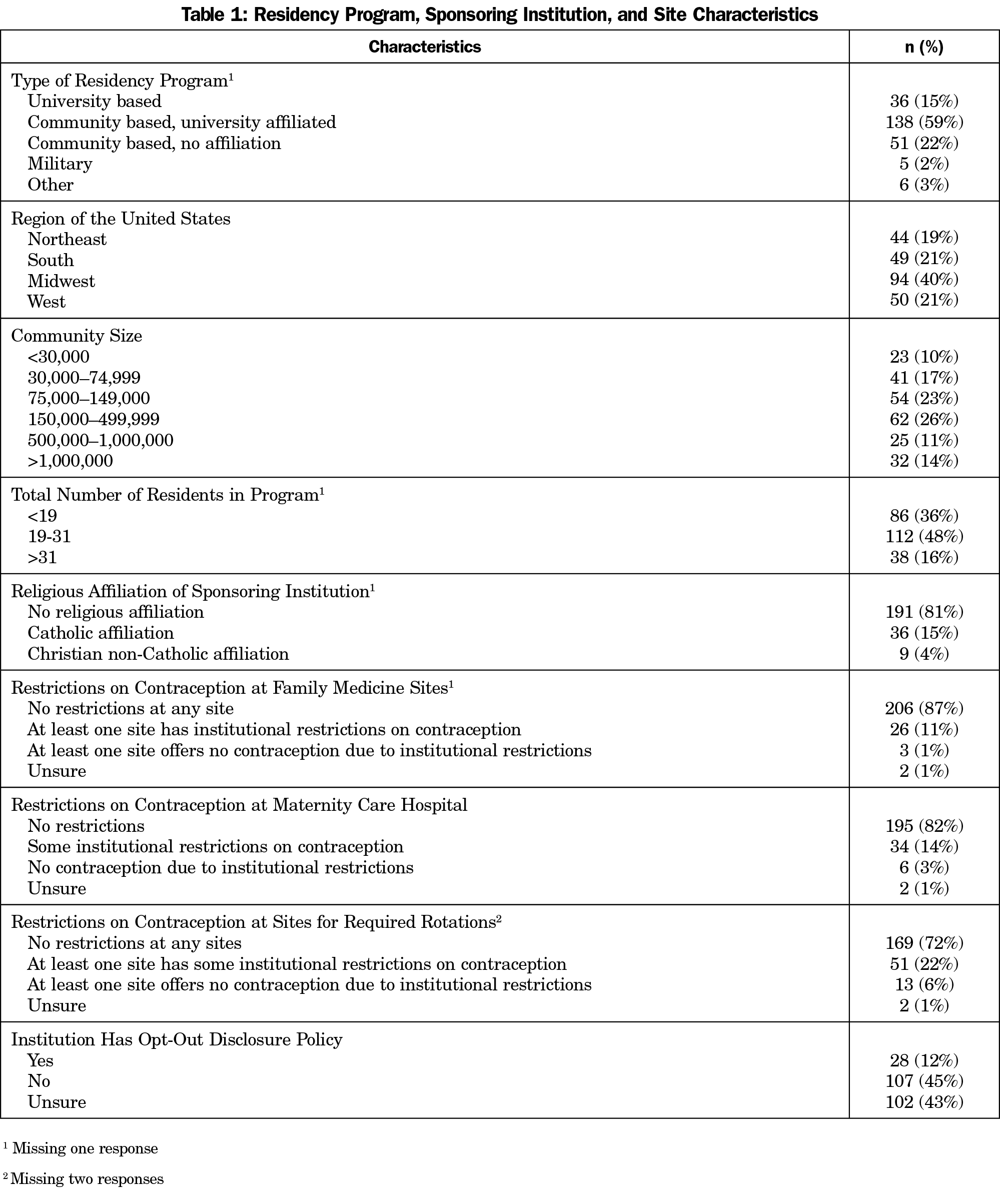

Of the 626 program directors in our final sample, 38% (237/626) responded to our questions. Programs of all types and from all geographic regions were represented (Table 1). Eighty-one percent had no religious affiliation, though 15% had Catholic affiliation. Table 2 shows percentages of program directors reporting any residents or faculty who opted out of providing pill/patch/ring (residents 27%; faculty 17%), emergency contraception (residents 40%, faculty 33%), or intrauterine devices (IUDs)/implants (resident 29%; faculty 23%).

Geographic location of the program was significantly associated with having at least one resident or faculty who opted out of providing any type of contraceptive service. Programs in the South had the highest percentage of programs with at least one opt-out resident (56%) or faculty (45%; Table 3). Catholic affiliation was significantly associated with presence of at least one opt-out faculty (53%). Programs with institutional restrictions on contraceptive provision were significantly associated with presence of at least one opt-out faculty (49%). In multivariate analysis, programs in the South (OR 2.78; 1.19-6.49) and programs with Catholic affiliation (OR 2.35; 1.23-4.91) had higher odds of having at least one opt-out faculty.

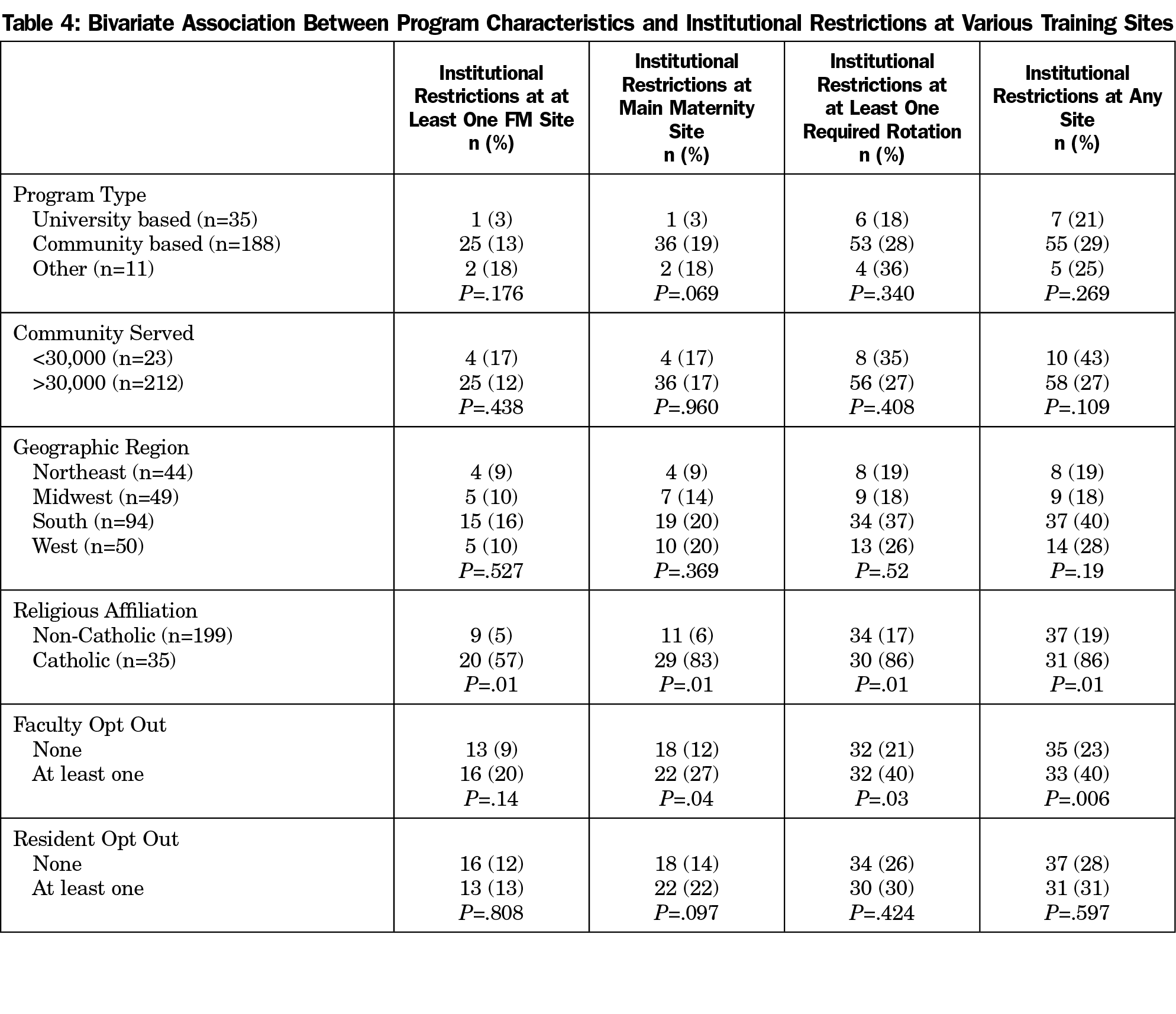

Religious affiliation and presence of at least one faculty opt out were associated with institutional restrictions on contraceptive provision at a family medicine training site (Table 4). Geographic region, Catholic affiliation, and having at least one opt-out faculty were significantly associated with institutional restrictions on contraception at any training site.

This survey of family medicine residency directors describes the landscape of faculty and resident opting out of providing contraception, as well as program characteristics associated with institutional restrictions on contraceptive services.

Though most programs reported no residents or faculty opting out of providing contraception, about one-third had one or more faculty opting out of some methods. Faculty opt out can impact patient access to contraceptive care on multiple levels. First, the opt-out faculty’s own patients may not be offered comprehensive contraception. Second, residents being supervised by opt-out faculty may have fewer contraceptive options to offer their patients. Finally, limited supervision in contraception could impact overall resident competency, resulting in a narrower scope of future contraceptive practice.

Catholic affiliation was associated with institutional restrictions on provision of contraceptive care across all sites. This association is expected since ethical and religious directives issued and enforced by the US Conference of Catholic Bishops explicitly prohibit Catholic hospitals from providing, encouraging, or condoning contraceptive methods other than natural family planning.7 This is important because the number of Catholic-owned or affiliated hospitals continues to rise. There is notable regional variation in Catholic hospital market share: some Midwestern and Western states have 40% or more of hospital beds in Catholic hospitals, whereas southern and northeastern states tend to have fewer.8

Given that faculty opt out can have multilevel impact on contraceptive access and our finding that programs with faculty opt outs are more likely located in the South or at Catholic-affiliated institutions, communities served by these programs are particularly affected. Since more than half of family physicians practice within 100 miles of their residency program,9 this association with opting out could impact contraceptive access in the South, which already has the highest rates of unintended pregnancy.10

Family medicine educators should improve communication regarding contraceptive practice restrictions. More than 40% of respondents did not know whether their institutions had policies requiring physicians to disclose to patients their personal decision to opt out of providing contraceptive services. Guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists states that when physicians do not provide standard reproductive health services, “they must provide potential patients with accurate and prior notice of their personal moral commitments.”11 While hospital policies on controversial topics may be informal or unwritten,12 program directors owe it to their learners and patients to know their institutional policies so that students can make informed decisions about their training and patients can get necessary contraceptive services.

The findings of this survey raise questions for future study about how faculty opting out and institutional restrictions affect trainees’ and patients’ experiences. For example, what is the range of services provided at clinics or hospitals that have “some” institutional restrictions on contraceptive services? How do residencies manage requests for contraception from patients of opt-out residents/faculty?

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. Our survey response rate was 38%, raising the possibility of sampling bias; however we had survey responders from all geographic regions, residency types, and community sizes. Residency directors may not be aware of the extent of opting out of contraception provision by their faculty and residents, resulting in possible underreporting. Finally, our study reports on program-level responses, so we do not know the exact number of faculty who opt out of providing each contraceptive method. The impact within the program on education and clinical care could be different and suggests further research is needed.

Family physicians are the largest physician specialty in the United States, providing more primary care visits than any other specialty. Family medicine training programs should consider the impact of restrictive contraceptive practices on their patients and learners. To meet learners’ needs, programs should be aware of and transparent regarding restrictions on contraceptive training and services.

References

- Herbitter C, Greenberg M, Fletcher J, Query C, Dalby J, Gold M. Family planning training in US family medicine residencies. Fam Med. 2011;43(8):574-581.

- Wu JP, Gundersen DA, Pickle S. Are the contraceptive recommendations of family medicine educators evidence-based? A CERA Survey. Fam Med. 2016;48(5):345-352.

- Liu Y, Hebert LE, Hasselbacher LA, Stulberg DB. “Am I going to be in trouble for what I’m doing?”: providing contraceptive care in religious health care systems. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2019;51(4):193-199. doi:10.1363/psrh.12125

- Lawrence RE, Rasinski KA, Yoon JD, Curlin FA. Obstetrician-gynecologist physicians’ beliefs about emergency contraception: a national survey. Contraception. 2010;82(4):324-330. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2010.04.151

- Lawrence RE, Rasinski KA, Yoon JD, Curlin FA. Factors influencing physicians’ advice about female sterilization in USA: a national survey. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(1):106-111. doi:10.1093/humrep/deq289

- Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW. Creating a centralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257-260. doi:10.1370/afm.2228

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services, Sixth Edition. Wasinginton, DC: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops; 2018. Accessed August 13, 2021. https://www.usccb.org/about/doctrine/ethical-and-religious-directives/upload/ethical-religious-directives-catholic-health-service-sixth-edition-2016-06.pdf

- Solomon T, Uttley L, HasBrouck P, Jung Y. Bigger and Bigger: The Growth of Catholic Health Systems. Boston, MA: Community Catalyst; 2020. Accessed February 16, 2021. https://www.communitycatalyst.org/resources/publications/document/2020-Cath-Hosp-Report-2020-31.pdf

- Fagan EB, Gibbons C, Finnegan SC, et al. Family medicine graduate proximity to their site of training: policy options for improving the distribution of primary care access. Fam Med. 2015;47(2):124-130.

- Kost K. Guttmacher Institute Unintended Pregnancy Rates at the State Level: Estimates for 2010 and Trends Since 2002. New York: Guttmacher Institute; January 2015. Accessed February 16, 2021. https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/stateup10.pdf

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. The limits of conscientious refusal in reproductive medicine. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 385. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:1203-1208. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000291561.48203.27

- Zeldovich VB, Rocca CH, Langton C, Landy U, Ly ES, Freedman LR. Abortion Policies in U.S. Teaching Hospitals: Formal and Informal Parameters Beyond the Law. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(6):1296-1305. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003876

There are no comments for this article.