As the medical community grapples with the effects of structural racism on health outcomes, recruitment of underrepresented minorities (URM) has become a prominent strategy to combat inequity.1-3 However, upon starting residency, URM physicians continue to face barriers throughout training.4-6 Research shows that many medical trainees experience harassment or discrimination, with women and URMs experiencing more discrimination than their peers.7-9 Existing surveys assessing resident experience generally do not address diversity, equity, or inclusion (DEI), and little data exists on experiences of diverse residents and faculty within their own programs.10 Inclusion, in particular, is often overlooked.11 This report describes our experiences developing and instituting a climate survey in our residency program to assess resident and faculty experiences and improve inclusivity, and provides a summary of findings and resulting DEI initiatives.

BRIEF REPORTS

Taking Our Own Temperature: Using a Residency Climate Survey to Support Minority Voices

Riley Smith, MD | Allison Johnson, MD | Alexandra Targan, MD | Cleveland Piggott, MD, MPH | Elizabeth Kvach, MD, MA

Fam Med. 2022;54(2):129-133.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2022.344019

Background and Objectives: Recruitment of underrepresented minorities (URM) in medicine has risen to the forefront as a strategy to address health inequities, but the experiences of URM residents within their own programs are poorly understood. We describe the development and implementation of a diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) climate survey at our residency program, the results of which have informed our DEI efforts.

Methods: A resident-faculty work group collaboratively developed an 81-item questionnaire, informed by other institutional climate surveys. We administered the survey annually from 2018 through 2021 to all residents and faculty at our large academic family medicine residency program. The anonymous survey covered six key areas: general climate, climate for specific group, personal experience with discrimination and harassment, recruitment, burnout, and curriculum.

Results: Average response rates were 84% and 50% for residents and faculty, respectively. Survey results show low satisfaction with resident and faculty diversity; higher rates of burnout for respondents who self-identify as URM, persons of color (POC), and/or LGBTQ; and racial and gender differences in experiences of workplace discrimination and sexual harassment.

Conclusions: Instituting an annual internal climate survey at our residency has provided invaluable information regarding the perspectives and experiences of our residents and faculty that has informed our DEI initiatives. We envision that our survey will inform continual improvement and serve as a model for similar introspection leading to meaningful action at other programs.

Survey Development

The University of Colorado Family Medicine Residency is a large opposed academic program with university, urban-underserved, and rural tracks. In 2017, faculty and residents established a working group committed to promoting social justice. The group developed a climate survey that was first administered in 2018, drawing on similar surveys from other institutions.12-15 Based on feedback, the survey was substantially revised in 2019, with only minor subsequent changes. Because the survey was administered for internal quality improvement purposes, the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board determined it did not require review.

Questionnaire

The 2019-2021 survey included 81 questions across six areas: general climate, climate for specific groups, discrimination experiences, recruitment, burnout, and curriculum.

Demographic questions included residency position, race, gender, and sexual orientation. General climate questions asked about the program’s supportiveness and responsiveness. In the “climate for specific groups” section, respondents were asked if residents and faculty are “treated with the same level of respect and given the same opportunities” as others based on gender identity, race, religion, sexual orientation, disability status, and family status. The “experiences” section asked whether respondents felt “unsupported, disrespected, or discriminated against” due to gender or race, and/or if they had experienced sexual harassment. “Recruitment” assessed satisfaction with program diversity and recruitment efforts. We assessed burnout with a validated single-item question.16 Curriculum questions are not presented here due to their specificity to our program.

Most questions used a 5-point agree/disagree Likert scale. Each section included a free-response space.

Analysis

We aggregated and analyzed results from 2019-2021.17,18 We calculated and compared descriptive statistics by race and gender using χ2 tests.

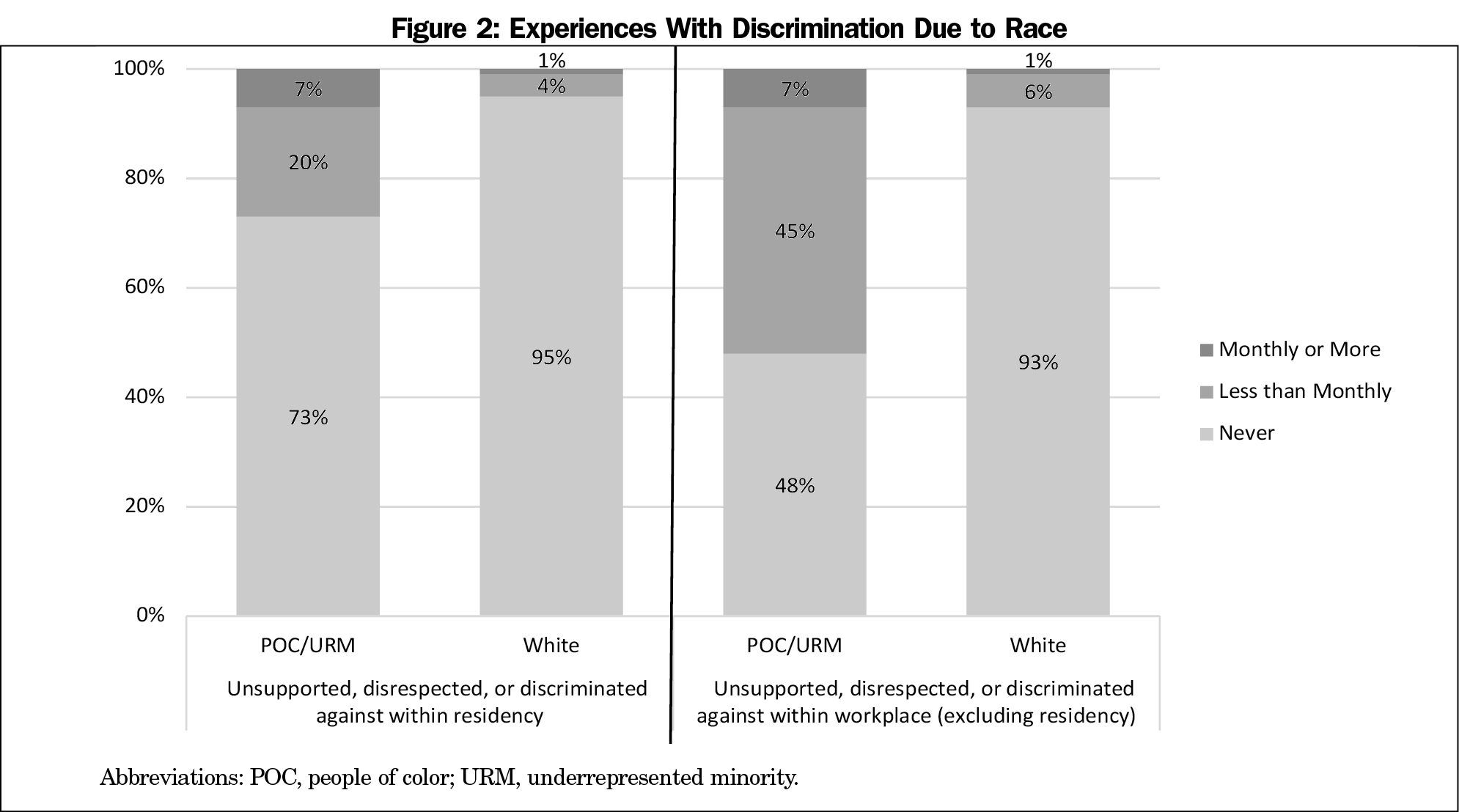

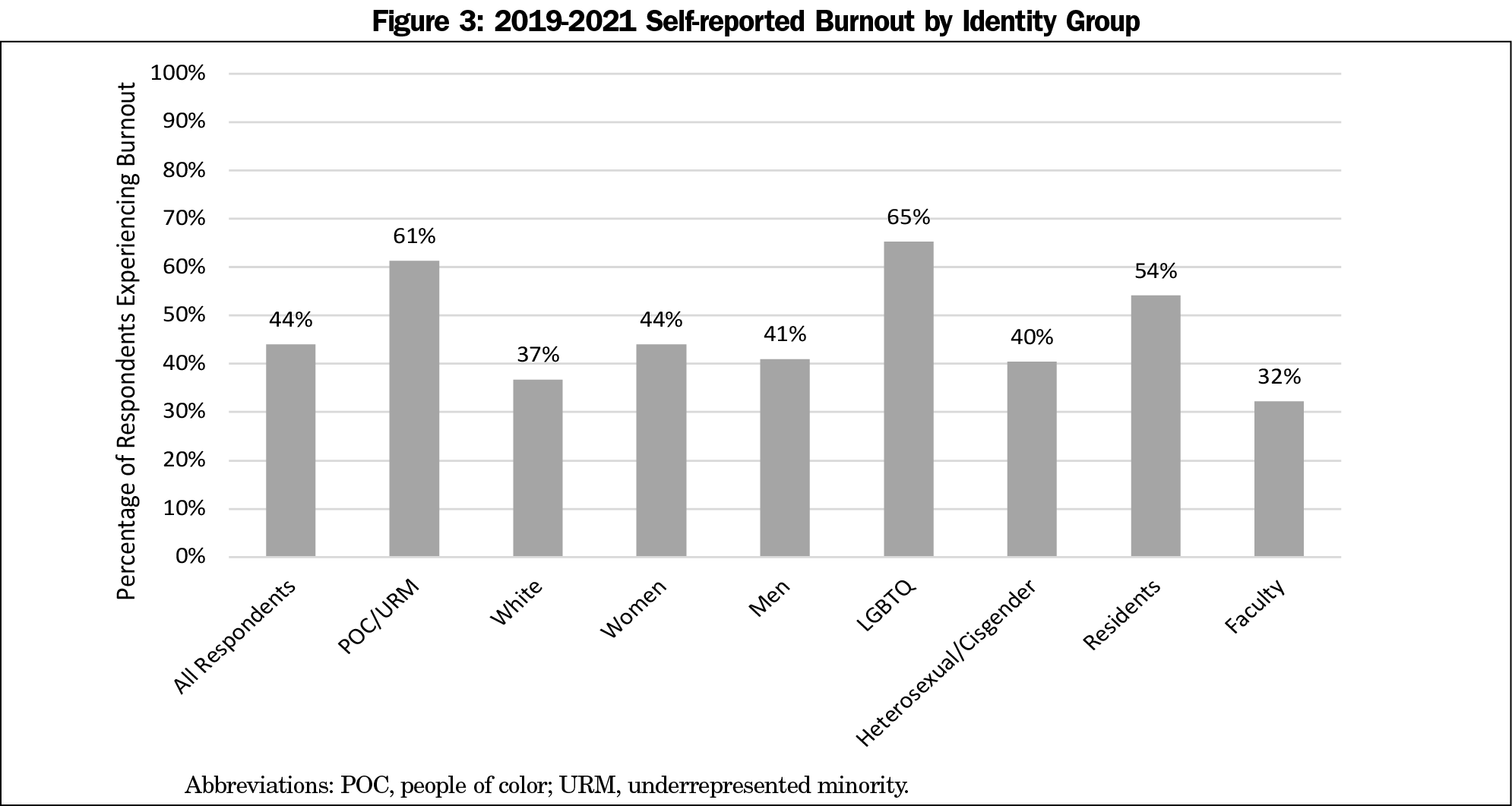

Each year, all residents (mean n=39) and faculty (mean n=67) were invited to participate. Mean pooled response rates were 84% and 50% for residents and faculty, respectively (Table 1).

General Climate

Most respondents agreed the climate is supportive and the residency values diversity. This result did not vary substantially between respondents or over time.

Climate for Specific Groups and Experiences With Discrimination and Harassment

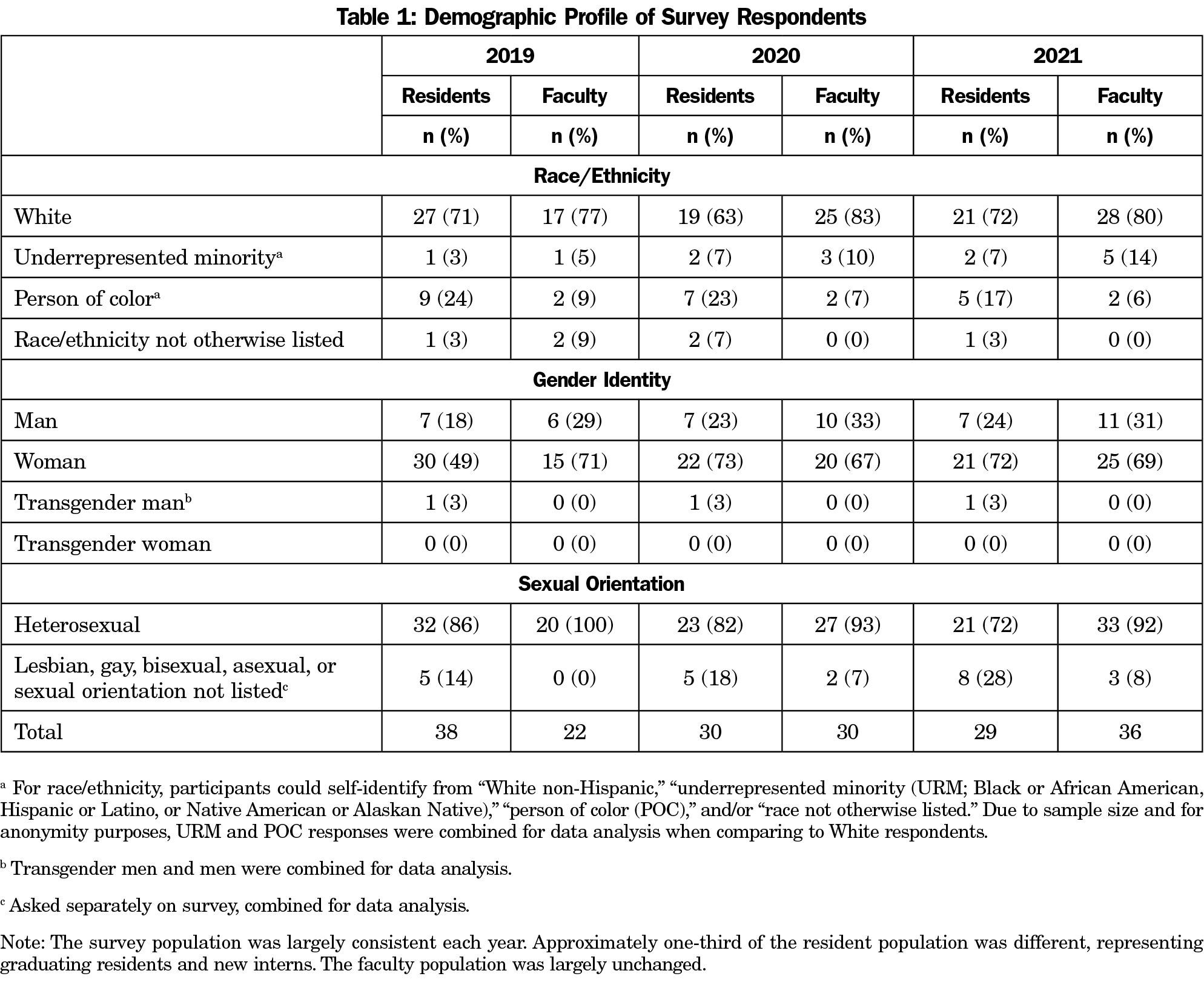

Women were more likely to ever experience discrimination due to gender, most commonly outside of the residency (women: 62%, n=84; men: 6%, n=3; P<.001; Figure 1).

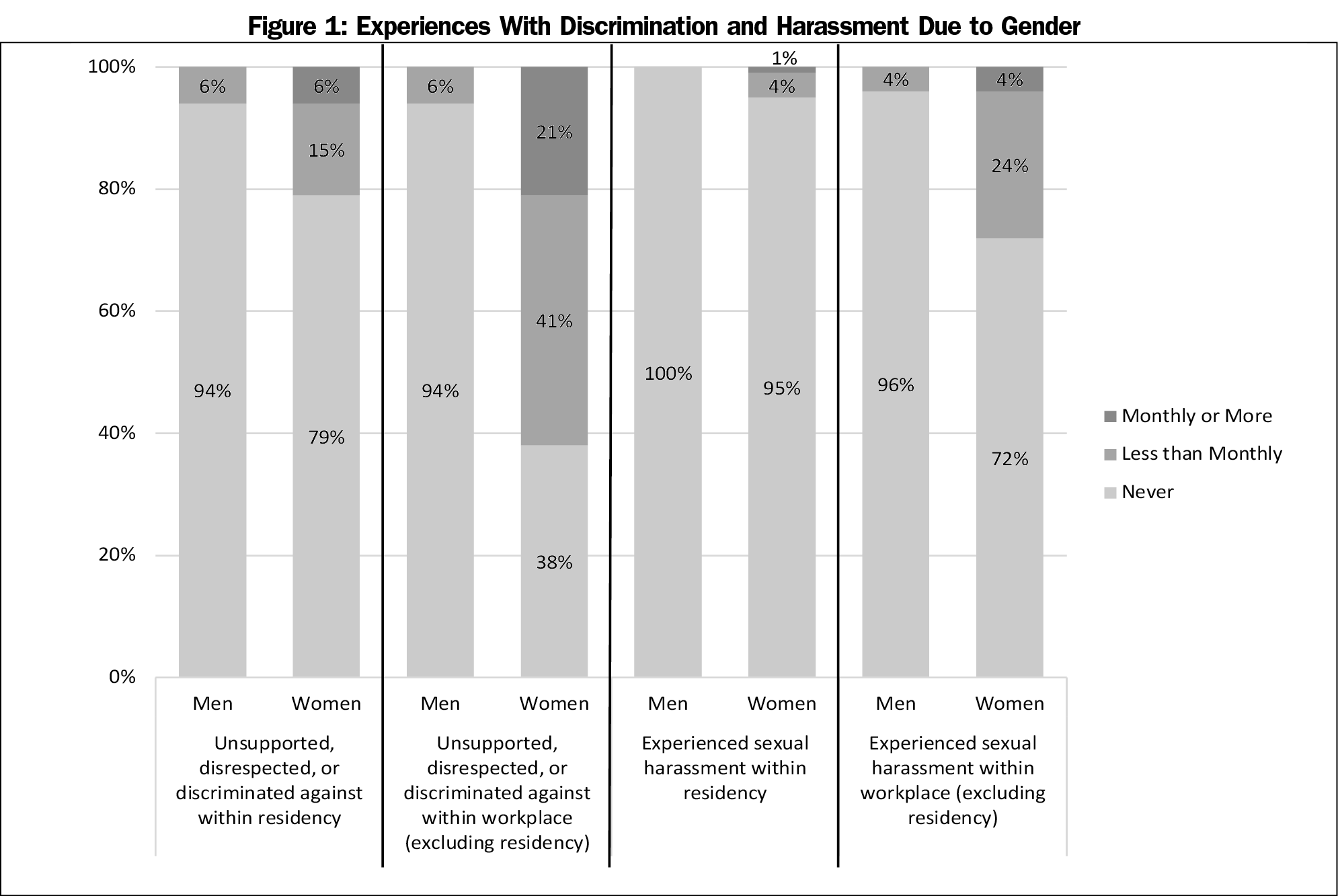

People of color (POC) and URM respondents were less likely to agree that “residents who are racial minorities are treated with the same level of respect and given the same opportunities as White people in this residency,” (POC/URM: 79% agree, n=34; White: 93% agree, n=117; P=.02). Regarding personal experiences with disrespect and discrimination, racial differences were most pronounced for instances that occurred outside the residency but within the workplace, with 52% of POC/URM respondents reporting this (n=23; Figure 2).

In 2021, when a question was added to clarify who perpetrated discrimination and/or harassment outside of the residency, the most common responses were “patients,” “patient family members,” and “off-service attendings.”

Recruitment

Respondents agreed that the program is making a genuine effort to recruit URM residents (92%, n=179) and residents of “other diverse identities (LGBTQ, socioeconomically diverse, etc)” (85%, n=163). Satisfaction regarding recruitment of URM faculty was lower but increased from 39% in 2019 (n=24) to 53% in 2021 (n=34).

Only 20% of respondents were satisfied with the number of URM residents (n=38), and 10% were satisfied with the number of URM faculty (n=19).

Burnout

While 44% of respondents overall reported burnout (n=85), POC/URM respondents reported higher rates than White respondents (POC/URM: 61%, n=27; White: 37%, n=50; P<.01). Sixty-five percent of LGBTQ respondents reported burnout (n=15) compared to 40% (n=63) of heterosexual/cisgender respondents (P=.02). Women (44%, n=59) and men (41%, n=21) reported similar rates (P=.75, Figure 3).

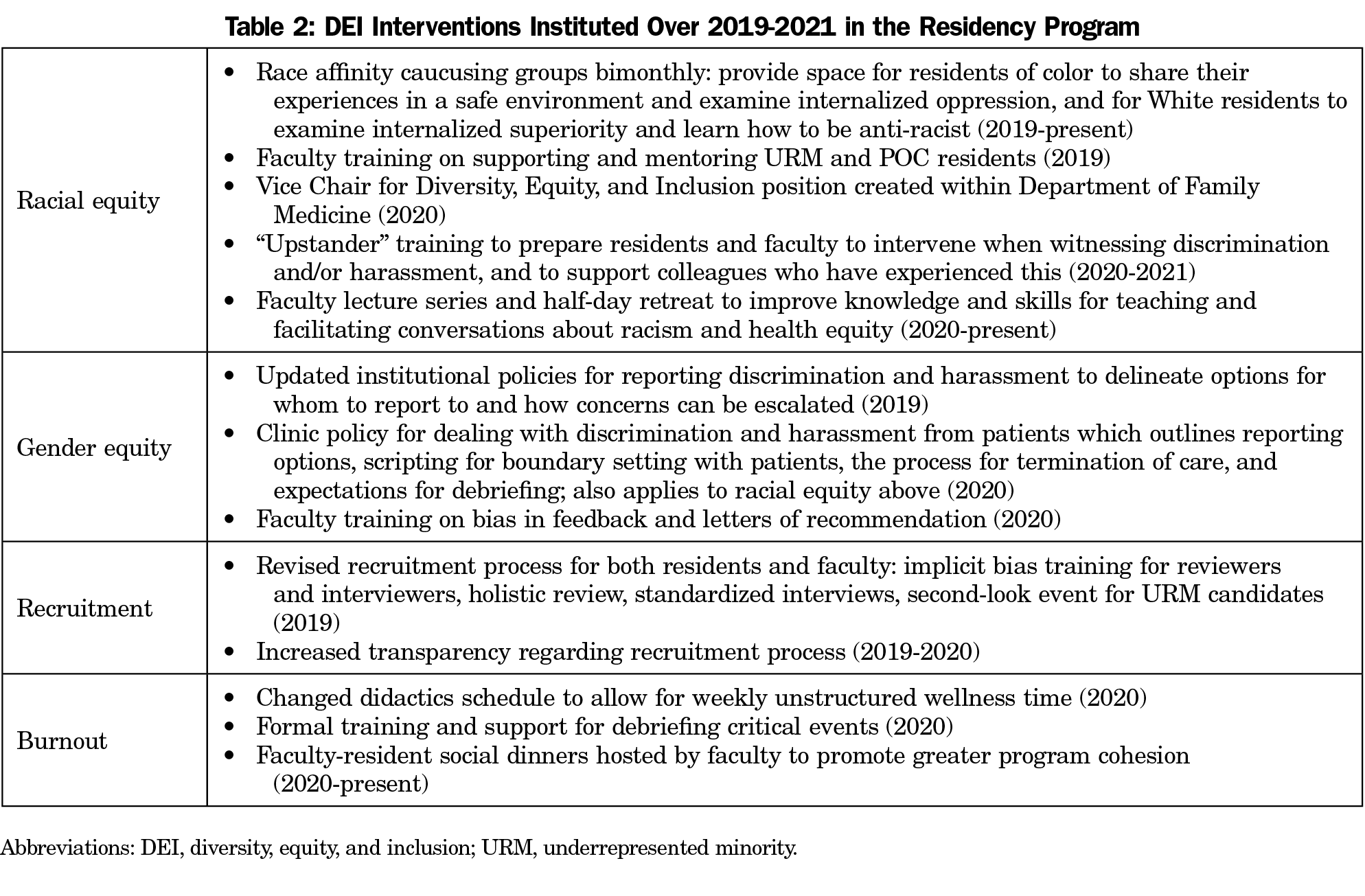

The climate survey provided us with invaluable data regarding resident and faculty experiences. Significant findings include higher burnout rates for URM/POC and LGBTQ respondents, low satisfaction with program diversity, and significant racial and gender differences with discrimination and harassment. These findings reflect existing literature on disparate experiences of URM and women trainees.4-7 We have used these results to affect significant changes in our DEI efforts (Table 2). Further research should explore burnout amongst URM/POC and LGBTQ residents and investigate interventions to reduce discrimination and harassment, particularly perpetrated by patients.19

Limitations of this analysis include evaluation of a single residency, which lessens generalizability, lack of survey validation, and the unmeasured impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, which profoundly affected residency experiences. The large number of women respondents and lower number of URM, POC, and LGBTQ respondents, while reflective of our program’s demographics, also likely impacted findings. Additionally, DEI interventions implemented during the 3 survey years likely affected findings, and we hope the survey will help us assess the efficacy of these interventions.

Nevertheless, this continuous self-assessment has been instrumental in identifying areas of concern and enacting meaningful change within our residency. Furthermore, conducting the survey demonstrates a culture of open inquiry and dialogue around DEI issues that can improve resident/faculty experience and promote inclusivity. It is critical that the medical community not only recruit a diverse workforce, but also use self-examination to create a truly inclusive environment for all. The pursuit of social justice at our program began by gathering information through the climate survey, but it cannot end there. By supporting minority voices, we envision informing continual improvements and inspiring similar introspection and meaningful action at other programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jodi Holtrop and Elizabeth Stanton for their manuscript review, the numerous members of the Social Justice Working Group who contributed to survey development and revisions, and our residency program leadership for their continued support of social justice and DEI initiatives.

Presentations: This study was presented at the STFM Annual Meeting (virtual), August, 24-27, 2020.

References

- Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X

- Cobbinah SS, Lewis J. Racism & Health: A public health perspective on racial discrimination. J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24(5):995-998. doi:10.1111/jep.12894

- Poole KG Jr, Jordan BL, Bostwick JM. Mission drift: are medical school admissions committees missing the mark on diversity? Acad Med. 2020;95(3):357-360. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003006

- Ackerman-Barger K, Boatright D, Gonzalez-Colaso R, Orozco R, Latimore D. Seeking inclusion excellence: understanding racial microaggressions as experienced by underrepresented medical and nursing students. Acad Med. 2020;95(5):758-763. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003077

- Hill KA, Samuels EA, Gross CP, et al. Assessment of the prevalence of medical student mistreatment by sex, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):653-665. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0030

- Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(5):487-496. doi:10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

- Fnais N, Soobiah C, Chen MH, et al. Harassment and discrimination in medical training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2014;89(5):817-827. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000200

- Hsiao CJ, Akhavan NN, Singh Ospina N, et al. Sexual harassment experiences across the academic medicine hierarchy. Cureus. 2021;13(2):e13508.

- de Bourmont SS, Burra A, Nouri SS, et al. Resident physician experiences with and responses to biased patients. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2021769. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21769

- Osseo-Asare A, Balasuriya L, Huot SJ, et al. Minority resident physicians’ views on the role of race/ethnicity in their training experiences in the workplace. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(5):e182723. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2723

- Roberts LW. Belonging, respectful inclusion, and diversity in medical education. Acad Med. 2020;95(5):661-664. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003215

- Major Survey Overview. Washington University in St Louis, Office of the Provost. Accessed February 18, 2018. https://diversity.wustl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/FINALGrad-Prof-Results.pdf

- Climate Survey. Harvard University Office of the Senior Vice Provost. Accessed February 18, 2018. https://faculty.harvard.edu/faculty-climate-survey

- Diversity Climate Survey. Case Western Reserve University Office for Inclusion, Diversity and Equal Opportunity. Accessed February 18, 2018. https://case.edu/diversity/about/diversity-climate-survey/

- Summary results of the 2007–08 Campus Climate Survey conducted by Sue Rankin and Associates. Carleton College. https://apps.carleton.edu/governance/diversity/archives/campus_climate_survey/results/. Accessed February 18, 2018

- Hansen V, Girgis A. Can a single question effectively screen for burnout in Australian cancer care workers? BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):341. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-10-341

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al; REDCap Consortium. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

- Lawrence JA, Davis BA, Corbette T, Hill EV, Williams DR, Reede JY. Racial/ethnic differences in burnout: a systematic review [published online ahead of print, 2021 Jan 11]. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;1-13. doi:10.1007/s40615-020-00950-0

Lead Author

Riley Smith, MD

Affiliations: Denver Health and Hospital Authority, Denver, CO

Co-Authors

Allison Johnson, MD - Denver Health and Hospital Authority, Denver, CO

Alexandra Targan, MD - University of Colorado School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine, Denver, CO

Cleveland Piggott, MD, MPH - University of Colorado School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine, Denver, CO

Elizabeth Kvach, MD, MA - Denver Health and Hospital Authority, Denver, CO

Corresponding Author

Elizabeth Kvach, MD, MA

Correspondence: University of Colorado-Denver, 1001 Yosemite St, Denver, CO 80230. 303-602-4545. Fax: 303-602-4550.

Email: elizabeth.kvach@dhha.org

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.