The novel coronavirus pandemic is an ongoing public health disaster, straining the capacities of hospitals, health systems, and the health care workforce. COVID-19 has raised concerns regarding the capacity and adequacy of the nation’s primary care infrastructure. With such pressures placed on organizations and their staff, retraining and redeployment of current medical professionals has been discussed as a viable strategy during such emergencies.1 Redeployment of workforce helps ensure patient needs are met, and can make best use of an available resource to respond to the pandemic. Family physicians have been trained in comprehensive, coordinated care, making them prime candidates for such redeployment. Success in COVID-19 response and recovery may depend on how well our health workforce is deployed and utilized.2 Therefore, the aim of this study is to describe sites of practice for family physicians to identify the potential for redeployment to a variety of settings in times of local, state, or national emergency.

BRIEF REPORTS

Family Medicine and Emergency Redeployment: Unrealized Potential

Hoon Byun, DrPH | John M. Westfall, MD, MPH

Fam Med. 2022;54(1):44-46.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2022.404532

Background and Objectives: Discussions of scope of practice among family physicians has become a crucial topic amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with new attention to residency training requirements. Family medicine has seen a gradual narrowing of practice due to a host of issues, including physician choice, expanding scope of practice from physician assistants and nurses, an increased emphasis on patient volume, clinical revenue, and residency training competency requirements. We sought to demonstrate the flexibility of the family medicine workforce as shown through their scopes of practice, and argue that this is indication of their potential for redeployment during emergencies.

Methods: This study computes scopes of practice for 78,416 family physicians who treat Medicare beneficiaries. We used Evaluation and Management (E/M) codes in Medicare’s 2017 Part-B public use file to calculate volumes of services done across six sites of service per physician. We aggregated counts and proportions of physicians and the E/M services they provided across sites of practice to characterize scope, and performed a separate analysis on rural physicians.

Results: The study found most family physicians practicing at a single site, namely, the ambulatory clinic. However, family physicians in rural areas, where need is greater, exhibit broader scope. This suggests that a significant number of family physicians have capacity for COVID-19 deployment into other settings, such as emergency rooms or hospitals.

Conclusions: Family physicians are a potential resource for emergency redeployment, however the current breadth of scope for most family physicians is not aligned with current residency training requirements and raises questions about the future of family medicine scope of practice.

We used data from the 2017 Medicare Fee for Service Physician and Other Supplier Public Use file, which is organized at the level of provider and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code. Focusing on family physicians treating the Medicare population, we used HCPCS codes associated with E/M services to identify six sites of practice common in family medicine (home visits, assisted living facilities, nursing homes, emergency rooms, hospitals, and office/clinic). We tallied services by site, and then summarized to the physician level. Summing the unique sites served as the basis for a physician’s scope of practice. We also computed counts and associated percentages of family physicians by scope and across sites. This analysis focused on the 78,416 family physicians in Medicare Part-B who practiced in at least one of these six sites. Central in this approach is the notion that these sites are associated with the activities that family physicians duly perform, indicating their scope of practice, and thus, their comprehensiveness.3-5 This was repeated for the subset of family physicians who practiced in rural counties as defined by the 2013 United States Department of Agriculture Rural-Urban Continuity Code designations.6 The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt from review.

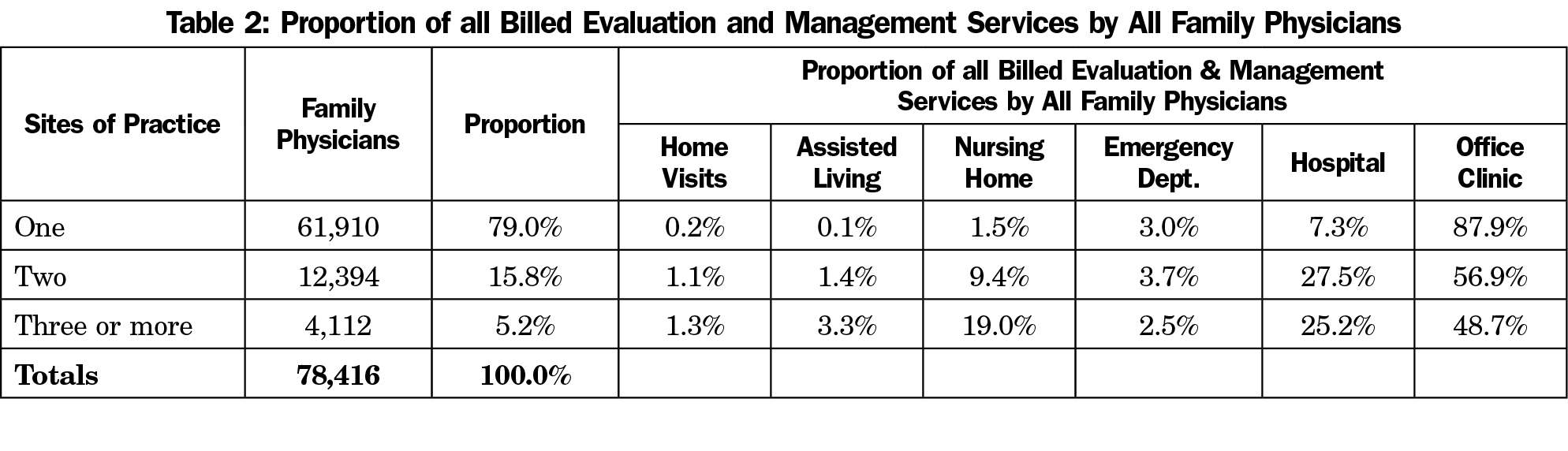

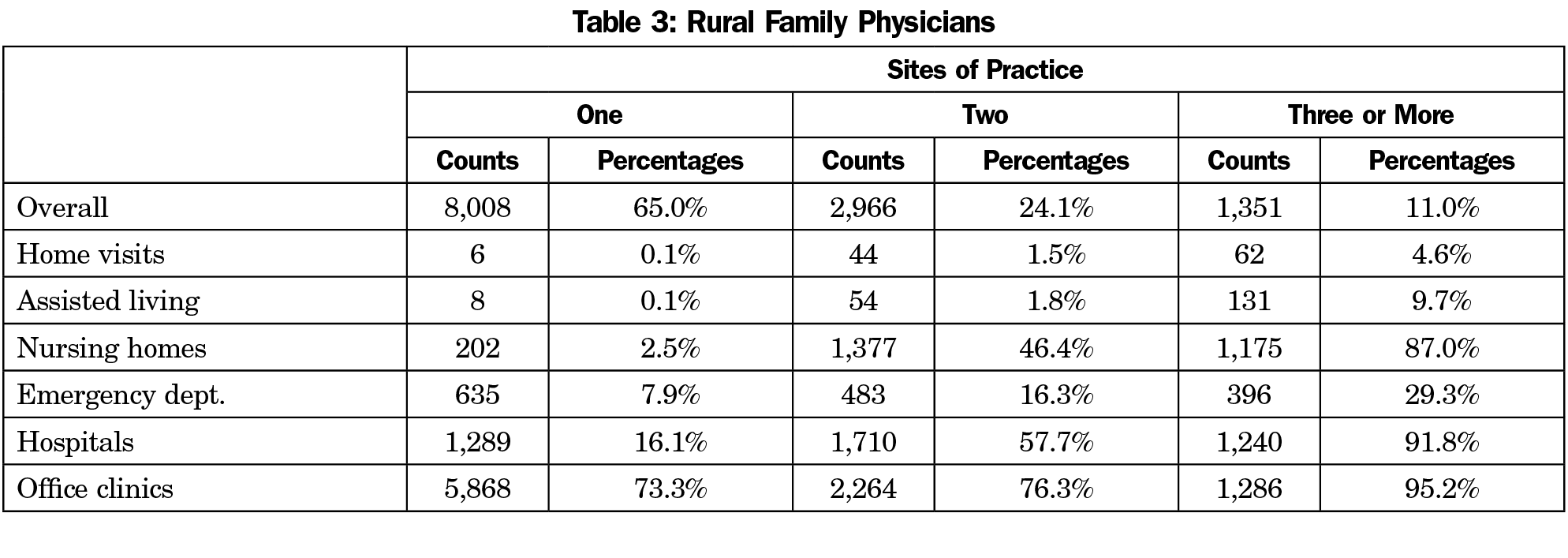

As shown in Table 1, 79% of family physicians in this Medicare sample practice at just one site type, of which 88% only practice in the office or ambulatory clinic (69% overall). Twenty-one percent of the entire sample and 35% of those in rural practice (Table 3) work at two or more sites, including hospitals, emergency departments, and nursing homes. Tables 2 and 4 describe the proportion of E/M services delivered in each of the delivery sites by all family physicians and rural family physicians, respectively. For physicians working in more than one site, the ambulatory clinic is still the most common based on the proportion of E/M services. Overall, 16,500 family physicians already work in multiple clinic sites, and could potentially be deployed during local, state, or national emergencies. Because family physicians receive training in a variety of practice sites, the current data suggest a large share of family physicians is not practicing at the top of their training.

Similar to prior studies, we have analyzed activities and procedures, determining the site of service to develop a measure of scope of practice.5 Most family physicians practice in a single location, the ambulatory clinic or office, but a significant number practice in multiple settings, suggesting broader comprehensiveness and providing a potential resource for redeployment to the variety of settings necessary for COVID-19 response, other emergency, or natural disaster.

Overall, 30% of family physicians and half of rural family physicians are providing some care outside the clinic or ambulatory setting, with many working in multiple settings. The benefits of multisite physician practice have been discussed as means to address physician shortages and improve access to care.7 The type of comprehensive care that family physicians can provide may serve as a basis for willing generalists to redeploy to other settings and address shortages during a widescale emergency.8 Current family medicine training is producing a workforce that can provide care in a variety of settings. Studies have found that redesign in family medicine residency curricula and length can encourage broader scope of practice and comprehensiveness of graduates.9-11 State and federal policies, curricular interventions in graduate education and residency, as well as ongoing education and training could facilitate expansion of the multisite family physician workforce. Family medicine board certification requires ongoing knowledge assessment of urgent, emergent, and hospital care. For family physicians who have not practiced in the hospital or emergency room, a brief retraining could quickly equip nearly all family physicians with the capacity to work in multiple settings.12 The current and potential broad scope and site of practice allows family physicians to meet the varied needs of the population, especially when facilities, specialties, or workforce are limited.

It is critical to continue graduate medical education in multiple sites of care for family physicians to be properly equipped to provide care where patients most need them. Taken together, these may further expand the pool of physicians capable of rapid redeployment or even rural practice.

COVID-19 reminds us of the versatility of family physicians, who are able to move between different sites of care to meet the needs of the community. We present evidence that suggests family physicians are capable of a wide scope of practice, however there may be a disconnect between that potential scope, and their current utilization. Regular certification and innovations in family medicine graduate medical education may help family physicians meet the varied needs of patients and communities.

References

- Frogner BK, Fraher EP, Spetz J, et al. Modernizing scope-of-practice regulations - time to prioritize patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(7):591-593. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1911077

- Fraher EP, Pittman P, Frogner BK, et al. Ensuring and sustaining a pandemic workforce. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(23):2181-2183. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2006376

- Schultz SE, Glazier RH. Identification of physicians providing comprehensive primary care in Ontario: a retrospective analysis using linked administrative data. MAJ Open; 2017. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20170083

- Chan BT. The declining comprehensiveness of primary care. CMAJ. 2002;166(4):429-434.

- Bazemore A, Petterson S, Peterson LE, Phillips RL Jr. More comprehensive care among family physicians is associated with lower costs and fewer hospitalizations. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(3):206-213. doi:10.1370/afm.1787

- Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Updated December 10, 2020. Accessed November 3, 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx

- Xierali IM. Physician multisite practicing: impact on access to care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(2):260-269. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.02.170287

- Devitt J, Malam N, Montgomery L. Bracing for impact: one family medicine residency program’s response to an impending COVID-19 surge. JABFM COVID-19 collection. Ahead-of-Print Subject Collection. Accessed October 4, 2020. https://www.jabfm.org/sites/default/files/COVID_20-0193.pdf

- Eiff MP, Hollander-Rodriguez J, Skariah J, et al. Scope of practice among recent family medicine residency graduates. Fam Med. 2017;49(8):607-617.

- Newton WP. Family physician scope of practice: what it is and why it matters. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(6):633-634. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2011.06.110262

- Wong E, Stewart M. Predicting the scope of practice of family physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(6):e219-e225.

- Coutinho AJ, Cochrane A, Stelter K, Phillips RL Jr, Peterson LE. Comparison of intended scope of practice for family medicine residents with reported scope of practice among practicing family physicians. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2364-2372. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.13734

Lead Author

Hoon Byun, DrPH

Affiliations: Robert Graham Center for Policy Research in Primary Care and Family Medicine, Washington, DC | and the American Academy of Family Physicians, Leawood, KS.

Co-Authors

John M. Westfall, MD, MPH - Robert Graham Center for Policy Research in Primary Care and Family Medicine, Washington, DC | and the American Academy of Family Physicians, Leawood, KS

Corresponding Author

Hoon Byun, DrPH

Correspondence: 1133 Connecticut Ave, Suite 1100, Washington, DC 20036. 202-655-4904.

Email: hbyun@aafp.org

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.